Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

Malaria is a severe disease caused by parasites of the genus Plasmodium, which is transmitted to humans by a bite of an infected female mosquito of the species Anopheles. Malaria remains the leading cause of mortality around the world, and early diagnosis and fast-acting treatment prevent unwanted outcomes. It is the most common disease in Africa and some countries of Asia, while in the developed world malaria occurs as imported from endemic areas.

- Anopheles

- antimalarials

- malaria

1. Malaria Treatment through History

1.1. Malaria in Europe

In Europe, malaria outbreaks occurred in the Roman Empire [63,64] and the 17th century. Up until the 17th century it was treated as any fever that people of the time encountered. The methods applied were not sufficient and included the release of blood, starvation, and body cleansing. As the first effective antimalarial drug, the medicinal bark of the Cinchona tree containing quinine was mentioned and was initially used by the Peruvian population [14]. It is believed that in the fourth decade of the 17th century it was transferred to Europe through the Spanish Jesuit missionaries who spread the treatment to Europe [65].

Contemporary knowledge of malaria treatment is the result of the work of a few researchers. Some of researchers are Alphonse Laveran, Ronald Ross, and Giovanni Battista Grassi. In November 1880, Laveran, who worked as a military doctor in Algeria, discovered the causative agents of malaria in the blood of mosquitoes and found that it was a kind of protozoa [66]. Laveran noticed that protozoa could, just like bacteria, live a parasitic way of life within humans and thus cause disease [66]. Nearly two decades later, more precisely in 1898, Ronald Ross, a military doctor in India, discovered the transmission of bird malaria in the saliva of infected mosquitos, while the Italian physician Giovanni Battista Grassi proved that malaria was transmitted from mosquitoes to humans, in the same year. He also proved that not all mosquitoes transmit malaria, but only a specific species (Anopheles) [17]. This discovery paved the way for further research.

The global battle against malaria started in 1955, and the program was based on the elimination of mosquitoes using DDT and included malarial areas of the United States, Southern Europe, the Caribbean, South Asia, but only three African countries (South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Swaziland). In 1975, the WHO announced that malaria had been eradicated in Europe and all recorded cases were introduced through migration [67,68].

1.2. Malaria in Croatia

In Croatia, the first written document that testifies to the prevention of malaria is the Statute of the town of Korčula from 1265. In 1874, the Law on Health Care of Croatia and Slavonia established the public health service that was directed towards treating malaria. There was no awareness nor proper medical knowledge about malaria, but the drainage was carried out to bring the ‘healthy air’ in the cities [69,70]. In 1798 physician Giuseppe Arduino notified the Austrian government about malaria in Istria. A government representative Vincenzo Benini accepted a proposed sanitary measure of the drainage of wetlands [71]. In 1864, the drainage of wetlands around Pula and on the coastal islands began, and since 1902 a program for the suppression of malaria by treatment of patients using quinine has been applied [72]. In 1922, the Institute for Malaria was founded in Trogir. In 1923, on the island of Krk, a project was started to eradicate malaria by the sanitation of water surfaces and the treatment of the patients with quinine, led by Dr. Otmar Trausmiller [66]. Since 1924, besides chemical treatment, biological control of mosquitoes has been established by introducing the fish Gambusia holbrooki to Istria and the coast [73]. In 1930 legislation was passed to enforce village sanitation, which included the construction of water infrastructure and safe wells, contributing to the prevention of malaria. Regular mosquito fogging with arsenic green (copper acetoarsenite) was introduced, and larvicidal disinfection of stagnant water was carried out.

Since malaria occurs near swamps, streams, ravines, and places where mosquitoes live near water, this disease has been present throughout history in Croatia, and it has often become an epidemic [74]. It was widespread in the area of Dalmatia, the Croatian Littoral region, Istria, and river flows. In the area of the Croatian Littoral, it was widespread on some islands, such as Krk, Rab, and Pag, while the mainland was left mainly clear of it [75]. The ethnographer Alberto Fortis (1741–1803) who traveled to Dalmatia, noted impressions recording details of malaria that was a problem in the Neretva River valley. Fortis wanted to visit that area, but the sailors on ship were afraid, probably because the were afraid to go to a place where there had been a disease outbreak known as the Neretva plague [76]. This Neretva plague was, in fact, malaria, and it is believed that due to it, the Neretva was nicknamed “Neretva—damned by God” [77,78]. Speaking of the Neretva region, Fortis states that the number of mosquitoes in that wetland area was so high that people had to sleep in stuffy canopy tents to defend themselves. Fortis also states that there were so many mosquitoes that he was affected by it. During the stay, Fortis met a priest who had a bump on the head claiming it had occurred after a mosquito bite and believed that the fever that infected the people of the Neretva Valley was also a consequence of the insect bites there [76]. In a manuscript, Dugački described some of the epidemics in Croatia. Thus, noted the small population of Nin in 1348, which was the result of the unhealthy air and high mortality of the population. Three centuries later, in 1646, the fever was mentioned in Novigrad, while the year 1717 was crucial for to the Istrian town of Dvigrad, which was utterly deserted due to malaria. At the beginning of the 20th century, more precisely in 1902, the daily press reported that the Provincial Hospital in Zadar was full of people affected by malaria. The extent to which this illness was widespread is proved by the fact that at the beginning of the 20th century about 180,000 people suffered from it in Dalmatia [18]. The volume and frequency of epidemics in Dalmatia resulted in the arrival of the Italian malariologist Grassi and the German parasitologist Schaudin. The procedures of quininization began to be applied, and in 1908 25 physicians and 423 pill distributors were to visit the villages and divide pills that had to be taken regularly to the people to eradicate malaria [75].

Likewise, in Slavonia, malaria had also a noticeable effect, and it was widespread in the 18th century due to a large number of swamps that covered the region. Such areas were extremely devastating for settlers who were more vulnerable to the disease than its domestic population [79]. Friedrich Wilhelm von Taube (1728–1778) recorded the disease and stated that the immigrant Germans were primarily affected by malaria and that the cities of Osijek and Petrovaradin can be nicknamed "German Cemeteries" [80]. According to Skenderović, the high mortality of German settlers from malaria was not limited only to the Slavonia region but also to the Danubian regions in which the Germans had settled in the 18th century, with Banat and Bačka [79] having the most significant number of malaria cases. The perception of Slavonia in the 18th century was not a positive one. Even Taube stated that Slavonia was not in good standing in the Habsburg Monarchy and that the nobility avoided living there. As some of the reasons for this avoidance, Taube mentioned the unhealthy air and the many swamps in the area around in which there was a multitude of insects. Taube noted that mosquitoes appear to be larger than in Germany and that its bite was much more painful. A change in the situation could only be brought about by drying the swamp, in his opinion [80]. Since malaria had led to the death of a large number of people, the solution had to be found to stop its further spread. Swamp drying was finally accepted by the Habsburg Monarchy and some European countries as a practical solution and, thus, its drainage began during the 18th century, resulting in cultivated fields [79].

Since epidemics of malaria continued to occur, there is one more significant record of the disease in the Medical Journal of 1877. In it, the physician A. Holzer cites his experiences from Lipik and Daruvar where he had been a spa physician for a long time. Holzer warns of the painful illness noticed at spa visitors suffering from the most in July and August. As a physician, Holzer could not remain indifferent to the fact that he did not see anyone looking healthy. It also pointed out that other parts of Croatia were not an exception. As an example, Holzer noted Virovitica County, where malaria was also widespread. He wanted to prevent the development and spread of the illness. Believing that preventing the toxic substances from rising into the air would stop the disease, the solution was to use charcoal that has the properties of absorbing various gases and, thus, prevents vapor rising from the ground [81].

Dr. Andrija Štampar (1888–1958) holds a prominent place in preventing the spread of malaria. Štampar founded the Department of Malaria, and numerous antimalaria stations, hygiene institutes, and homes of national health. Dr. Štampar devoted his life to educating the broader population about healthy habits and, thus, prevents the spread of infectious diseases. Many films were shown, including a film entitled ‘Malaria of Trogir’ in Osijek in 1927, with numerous health lectures on malaria [82]. After the end of the Second World War, a proposal for malaria eradication measures was drafted by Dr. Branko Richter. These measures, thanks to Dr. Andrija Štampar, are being used in many malaria-burdened countries. For the eradication of malaria in Croatia and throughout Yugoslavia, DDT has been used since 1947 [83].

Malaria is still one of the most infectious diseases that cause far more deaths than all parasitic diseases together. Malaria was eradicated in Europe in 1975. After that year, malaria cases in Europe are linked to travel and immigrants coming from endemic areas. Although the potential for malaria spreading in Europe is very low, especially in its western and northern parts, it is still necessary to raise awareness of this disease and keep public health at a high level in order to prevent the possibility of transmitting the disease to the most vulnerable parts of Europe [84].

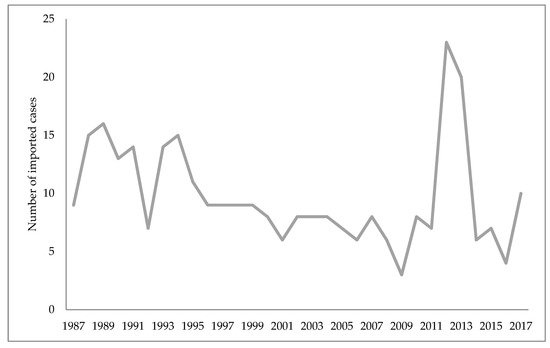

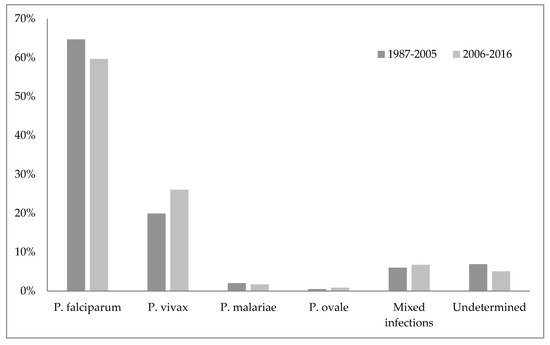

Unofficial data show that malaria disappeared from Croatia in 1958, while the World Health Organization cites 1964 as the year when malaria was officially eradicated in Croatia [45,75]. Nonetheless, some cases of imported malaria have been reported in Croatia since 1964. The imported malaria is evident concerning Croatia’s orientation to maritime affairs, tourism, and business trips. Namely, malaria is introduced to Croatia by foreign and domestic sailors, and in rare cases by tourists, mainly from the countries of Africa and Asia [75,85]. According to the reports of the Croatian Institute of Public Health, since the eradication of this disease 423 malaria cases have been reported, all imported [86]. Figure 1 shows the number of imported malaria cases in Croatia from 1987–2017, and Figure 2 the causative Plasmodium species of those cases (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [86,87].

Figure 1. Imported malaria cases in Croatia from 1987–2017.

Figure 2. The causative agents of imported malaria in Croatia.

There is also massive and uncontrollable migration from Africa and Asia (mostly due to climate change) of both humans and birds, from countries with confirmed epidemics. This issue is an insurmountable problem if measured by the traditional approach. Insecticides (DDT, malathion, etc.) synthetic pyrethroids, in addition to inefficiency, impact the environment (harm bees, fruits, vines, etc.). Consequently, scientists have patiently established a mosquito control strategy (University of Grenoble, Montpellier) which includes a meticulous solution to the mosquito vector effect (malaria, arbovirus infection, West Nile virus) by changes in agriculture, urbanism, public services hygiene [88].

Northeastern Slavonia is committed to applying methods that are consistent with such achievements, with varying success, as certain limitations apply to protected natural habitats (Kopački rit) [89].

There is a historical link between population movement and global public health. Due to its unique geostrategic position, in the past, Croatia has been the first to experience epidemics that came to Europe through land and sea routes from the east. Adriatic ports and international airports are still a potential entry for the import of individual cases of communicable diseases. Over the past few years, sailors, as well as soldiers who worked in countries with endemic malaria, played a significant role in importing malaria into Croatia. Successful malaria eradication has been carried out in Croatia. Despite that in Croatia are still many types of Anopheles, which means that the conditions of transmission of the imported malaria from the endemic areas still exist. The risk of malaria recrudesce is determined by the presence of the vector, but also by the number of infected people in the area. Due to climate change, it is necessary to monitor the vectors and people at risk of malaria. Naturally- and artificially-created catastrophes, such as wars and mass people migration from endemic areas, could favor recrudescing of malaria. Once achieved, eradication would be maintained if the vector capacities are low and prevention measures are implemented. The increased number of malaria cases worldwide, the recrudesce of indigenous malaria cases in the countries where the disease has been eradicated, the existence of mosquitoes that transmit malaria and the number of imported malaria cases in Croatia are alarming facts. Health surveillance, including obligatory and appropriate prophylaxis for travelers to endemic areas, remains a necessary public health care measure pointed at managing malaria in Croatia.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms7060179

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!