The term nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was defined in the 1980s to describe exceeding hepatocellular triacylglycerol accumulation in absence of significant alcohol intake, viral and autoimmune liver disease. The course of NAFLD was long thought to follow the so-called “two hit hypothesis. Manifestation of bland steatosis (nonalcoholic fatty liver, NAFL) was defined as first hit, while signs of liver inflammation, hepatocyte injury and fibrosis, becoming evident in varying percentages of patients, were proposed as succeeding second hit. Presence of these pathologies can be evaluated histologically, using defined staging and grading systems, and is termed then nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Steatosis can alternatively be evaluated by noninvasive approaches.

- insulin resistance

- type 2 diabetes

- nonexercise activity thermogenesis

- AMP activated protein kinase

1. Insulin Resistance as Trigger Event for NAFLD Onset, Progression, and Clinical Course

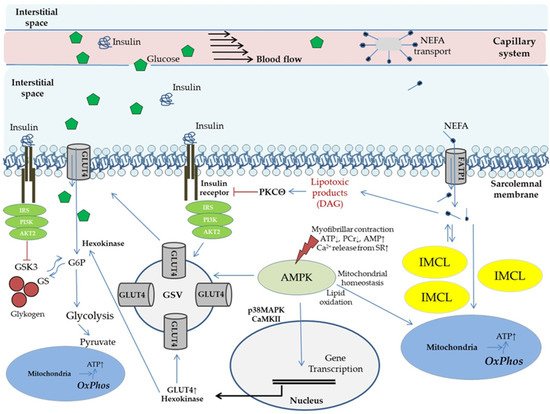

2. The Concept of Metabolic Flexibility: Molecular Mechanisms of Physical Activity on Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Signaling in Skeletal Muscle

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines9121853

References

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1.

- Stefan, N.; Häring, H.-U.; Cusi, K. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Causes, diagnosis, cardiometabolic consequences, and treatment strategies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 313–324.

- Farrell, G.C.; van Rooyen, D.; Gan, L.; Chitturi, S. NASH is an Inflammatory Disorder: Pathogenic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications. Gut Liver 2012, 6, 149–171.

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R.; Roden, M. NAFLD and diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 32–42.

- Söderberg, C.; Stål, P.; Askling, J.; Glaumann, H.; Lindberg, G.; Marmur, J.; Hultcrantz, R. Decreased survival of subjects with elevated liver function tests during a 28-year follow-up. Hepatology 2010, 51, 595–602.

- Angulo, P.; Kleiner, D.E.; Dam-Larsen, S.; Adams, L.A.; Bjornsson, E.S.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Mills, P.R.; Keach, J.C.; Lafferty, H.D.; Stahler, A.; et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated with Long-term Outcomes of Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 389–397.e10.

- Ekstedt, M.; Hagström, H.; Nasr, P.; Fredrikson, M.; Stål, P.; Kechagias, S.; Hultcrantz, R. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1547–1554.

- Bertot, L.C.; Adams, L.A. The Natural Course of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 774.

- Kim, G.-A.; Lee, H.C.; Choe, J.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, M.J.; Chang, H.-S.; Bae, I.Y.; Kim, H.-K.; An, J.; Shim, J.H.; et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cancer incidence rate. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 140–146.

- Hagström, H.; Nasr, P.; Ekstedt, M.; Hammar, U.; Stål, P.; Hultcrantz, R.; Kechagias, S. Fibrosis stage but not NASH predicts mortality and time to development of severe liver disease in biopsy-proven NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2017, 67, 1265–1273.

- Lu, H.; Liu, H.; Hu, F.; Zou, L.; Luo, S.; Sun, L. Independent Association between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 2013, 124958.

- Than, N.N.; Newsome, P.N. A concise review of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Atherosclerosis 2015, 239, 192–202.

- Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, K.J.; Yoo, M.E.; Kim, G.; Yoon, H.-J.; Jo, K.; Youn, J.-C.; Yun, M.; Park, J.Y.; Shim, C.Y.; et al. Association of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with subclinical myocardial dysfunction in non-cirrhotic patients. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 764–772.

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An emerging driving force in chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 297–310.

- Yeung, M.-W.; Wong, G.L.-H.; Choi, K.C.; Luk, A.O.-Y.; Kwok, R.; Shu, S.S.-T.; Chan, A.W.-H.; Lau, E.S.H.; Ma, R.C.W.; Chan, H.L.-Y.; et al. Advanced liver fibrosis but not steatosis is independently associated with albuminuria in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 147–156.

- Buckley, A.J.; Thomas, E.L.; Lessan, N.; Trovato, F.M.; Trovato, G.M.; Taylor-Robinson, S.D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Relationship with cardiovascular risk markers and clinical endpoints. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 144, 144–152.

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; Greten, T.F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease promotes hepatocellular carcinoma through direct and indirect effects on hepatocytes. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 752–762.

- Huber, Y.; Labenz, C.; Michel, M.; Wörns, M.-A.; Galle, P.R.; Kostev, K.; Schattenberg, J.M. Tumor Incidence in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2020, 117, 719–724.

- Fukunaga, S.; Nakano, D.; Kawaguchi, T.; Eslam, M.; Ouchi, A.; Nagata, T.; Kuroki, H.; Kawata, H.; Abe, H.; Nouno, R.; et al. Non-Obese MAFLD Is Associated with Colorectal Adenoma in Health Check Examinees: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5462.

- Koskinas, J.; Gomatos, I.P.; Tiniakos, D.G.; Memos, N.; Boutsikou, M.; Garatzioti, A.; Archimandritis, A.; Betrosian, A. Liver histology in ICU patients dying from sepsis: A clinico-pathological study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 1389–1393.

- Shaker, M.; Tabbaa, A.; Albeldawi, M.; Alkhouri, N. Liver transplantation for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: New challenges and new opportunities. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 5320–5330.

- Wong, R.J.; Cheung, R.; Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014, 59, 2188–2195.

- Wang, X.; Li, J.; Riaz, D.R.; Shi, G.; Liu, C.; Dai, Y. Outcomes of liver transplantation for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 394–402.

- Hoppe, S.; von Loeffelholz, C.; Lock, J.F.; Doecke, S.; Sinn, B.V.; Rieger, A.; Malinowski, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H.; Neuhaus, P.; Stockmann, M. Nonalcoholic steatohepatits and liver steatosis modify partial hepatectomy recovery. J. Investig. Surg. 2015, 28, 24–31.

- Stepanova, M.; Henry, L.; Garg, R.; Kalwaney, S.; Saab, S.; Younossi, Z. Risk of de novo post-transplant type 2 diabetes in patients undergoing liver transplant for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015, 15, 175.

- Golabi, P.; Otgonsuren, M.; de Avila, L.; Sayiner, M.; Rafiq, N.; Younossi, Z.M. Components of metabolic syndrome increase the risk of mortality in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Medicine 2018, 97, e0214.

- Sommerfeld, O.; von Loeffelholz, C.; Diab, M.; Kiessling, S.; Doenst, T.; Bauer, M.; Sponholz, C. Association between high dose catecholamine support and liver dysfunction following cardiac surgery. J. Card. Surg. 2020, 35, 1228–1236.

- Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. NAFLD: A multisystem disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S47–S64.

- Paik, J.M.; Golabi, P.; Biswas, R.; Alqahtani, S.; Venkatesan, C.; Younossi, Z.M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Alcoholic Liver Disease are Major Drivers of Liver Mortality in the United States. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 890–903.

- Skyler, J.S.; Bakris, G.L.; Bonifacio, E.; Darsow, T.; Eckel, R.H.; Groop, L.; Groop, P.-H.; Handelsman, Y.; Insel, R.A.; Mathieu, C.; et al. Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis. Diabetes 2017, 66, 241–255.

- von Loeffelholz, C.; Coldewey, S.M.; Birkenfeld, A.L. A Narrative Review on the Role of AMPK on De Novo Lipogenesis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Evidence from Human Studies. Cells 2021, 10, 1822.

- Lewis, G.F.; Carpentier, A.; Adeli, K.; Giacca, A. Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Endocr. Rev. 2002, 23, 201–229.

- Bril, F.; Barb, D.; Portillo-Sanchez, P.; Biernacki, D.; Lomonaco, R.; Suman, A.; Weber, M.H.; Budd, J.T.; Lupi, M.E.; Cusi, K. Metabolic and histological implications of intrahepatic triglyceride content in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2017, 65, 1132–1144.

- Jonker, J.T.; de Laet, C.; Franco, O.H.; Peeters, A.; Mackenbach, J.; Nusselder, W.J. Physical activity and life expectancy with and without diabetes: Life table analysis of the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 38–43.

- Sigal, R.J.; Kenny, G.P.; Wasserman, D.H.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C.; White, R.D. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1433–1438.

- Kirwan, J.P.; Sacks, J.; Nieuwoudt, S. The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2017, 84, S15–S21.

- Golabi, P.; Gerber, L.; Paik, J.M.; Deshpande, R.; de Avila, L.; Younossi, Z.M. Contribution of sarcopenia and physical inactivity to mortality in people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2020, 2, 100171.

- Tokushige, K.; Ikejima, K.; Ono, M.; Eguchi, Y.; Kamada, Y.; Itoh, Y.; Akuta, N.; Yoneda, M.; Iwasa, M.; Yoneda, M.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis 2020. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 951–963.

- Kelley, D.E. Skeletal muscle fat oxidation: Timing and flexibility are everything. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1699–1702.

- Corpeleijn, E.; Saris, W.H.M.; Blaak, E.E. Metabolic flexibility in the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: Effects of lifestyle. Obes. Rev. 2009, 10, 178–193.

- Goodpaster, B.H.; Sparks, L.M. Metabolic Flexibility in Health and Disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1027–1036.

- Smith, R.L.; Soeters, M.R.; Wüst, R.C.I.; Houtkooper, R.H. Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 489–517.

- Colberg, S.R.; Simoneau, J.A.; Thaete, F.L.; Kelley, D.E. Skeletal muscle utilization of free fatty acids in women with visceral obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 1846–1853.

- Samuel, V.T.; Shulman, G.I. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease as a Nexus of Metabolic and Hepatic Diseases. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 22–41.

- Petersen, K.F.; Shulman, G.I. Pathogenesis of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Cardiol. 2002, 90, 11G–18G.

- Ng, J.M.; Azuma, K.; Kelley, C.; Pencek, R.; Radikova, Z.; Laymon, C.; Price, J.; Goodpaster, B.H.; Kelley, D.E. PET imaging reveals distinctive roles for different regional adipose tissue depots in systemic glucose metabolism in nonobese humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E1134–E1141.

- Haddad, F.; Adams, G.R. Selected contribution: Acute cellular and molecular responses to resistance exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 394–403.

- Henriksen, E.J. Invited review: Effects of acute exercise and exercise training on insulin resistance. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 788–796.

- Zierath, J.R. Invited review: Exercise training-induced changes in insulin signaling in skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 773–781.

- Sakamoto, K.; Goodyear, L.J. Invited review: Intracellular signaling in contracting skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002, 93, 369–383.

- Roden, M. How free fatty acids inhibit glucose utilization in human skeletal muscle. News Physiol. Sci. 2004, 19, 92–96.

- Holloszy, J.O. Exercise-induced increase in muscle insulin sensitivity. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 338–343.

- Richter, E.A.; Hargreaves, M. Exercise, GLUT4, and skeletal muscle glucose uptake. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 993–1017.

- Hegarty, B.D.; Turner, N.; Cooney, G.J.; Kraegen, E.W. Insulin resistance and fuel homeostasis: The role of AMP-activated protein kinase. Acta Physiol. 2009, 196, 129–145.

- Petersen, M.C.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 2133–2223.

- Herzig, S.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 121–135.

- Nielsen, S.; Guo, Z.; Johnson, C.M.; Hensrud, D.D.; Jensen, M.D. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 1582–1588.

- Roden, M. Mechanisms of Disease: Hepatic steatosis in type 2 diabetes—Pathogenesis and clinical relevance. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 2, 335–348.

- Roden, M.; Price, T.B.; Perseghin, G.; Petersen, K.F.; Rothman, D.L.; Cline, G.W.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanism of free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 97, 2859–2865.

- Abbasi, F.; McLaughlin, T.; Lamendola, C.; Reaven, G.M. The relationship between glucose disposal in response to physiological hyperinsulinemia and basal glucose and free fatty acid concentrations in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1251–1254.

- Amati, F.; Dubé, J.J.; Alvarez-Carnero, E.; Edreira, M.M.; Chomentowski, P.; Coen, P.M.; Switzer, G.E.; Bickel, P.E.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Toledo, F.G.S.; et al. Skeletal muscle triglycerides, diacylglycerols, and ceramides in insulin resistance: Another paradox in endurance-trained athletes? Diabetes 2011, 60, 2588–2597.

- Coen, P.M.; Menshikova, E.V.; Distefano, G.; Zheng, D.; Tanner, C.J.; Standley, R.A.; Helbling, N.L.; Dubis, G.S.; Ritov, V.B.; Xie, H.; et al. Exercise and Weight Loss Improve Muscle Mitochondrial Respiration, Lipid Partitioning, and Insulin Sensitivity After Gastric Bypass Surgery. Diabetes 2015, 64, 3737–3750.

- Chee, C.; Shannon, C.E.; Burns, A.; Selby, A.L.; Wilkinson, D.; Smith, K.; Greenhaff, P.L.; Stephens, F.B. Relative Contribution of Intramyocellular Lipid to Whole-Body Fat Oxidation Is Reduced with Age but Subsarcolemmal Lipid Accumulation and Insulin Resistance Are Only Associated with Overweight Individuals. Diabetes 2016, 65, 840–850.

- Lee, H.-Y.; Choi, C.S.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Alves, T.C.; Jornayvaz, F.R.; Jurczak, M.J.; Zhang, D.; Woo, D.K.; Shadel, G.S.; Ladiges, W.; et al. Targeted expression of catalase to mitochondria prevents age-associated reductions in mitochondrial function and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 668–674.

- Morino, K.; Petersen, K.F.; Dufour, S.; Befroy, D.; Frattini, J.; Shatzkes, N.; Neschen, S.; White, M.F.; Bilz, S.; Sono, S.; et al. Reduced mitochondrial density and increased IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 3587–3593.

- Cleland, P.J.; Appleby, G.J.; Rattigan, S.; Clark, M.G. Exercise-induced translocation of protein kinase C and production of diacylglycerol and phosphatidic acid in rat skeletal muscle in vivo. Relationship to changes in glucose transport. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 17704–17711.

- Ishizuka, T.; Cooper, D.R.; Hernandez, H.; Buckley, D.; Standaert, M.; Farese, R.V. Effects of insulin on diacylglycerol-protein kinase C signaling in rat diaphragm and soleus muscles and relationship to glucose transport. Diabetes 1990, 39, 181–190.

- You, J.-S.; Lincoln, H.C.; Kim, C.-R.; Frey, J.W.; Goodman, C.A.; Zhong, X.-P.; Hornberger, T.A. The role of diacylglycerol kinase ζ and phosphatidic acid in the mechanical activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 1551–1563.

- Koliaki, C.; Szendroedi, J.; Kaul, K.; Jelenik, T.; Nowotny, P.; Jankowiak, F.; Herder, C.; Carstensen, M.; Krausch, M.; Knoefel, W.T.; et al. Adaptation of hepatic mitochondrial function in humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver is lost in steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 739–746.

- Szendroedi, J.; Roden, M. Mitochondrial fitness and insulin sensitivity in humans. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 2155–2167.

- Boushel, R.; Lundby, C.; Qvortrup, K.; Sahlin, K. Mitochondrial plasticity with exercise training and extreme environments. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2014, 42, 169–174.

- Steenberg, D.E.; Jørgensen, N.B.; Birk, J.B.; Sjøberg, K.A.; Kiens, B.; Richter, E.A.; Wojtaszewski, J.F.P. Exercise training reduces the insulin-sensitizing effect of a single bout of exercise in human skeletal muscle. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 89–103.

- Lundby, A.-K.M.; Jacobs, R.A.; Gehrig, S.; de Leur, J.; Hauser, M.; Bonne, T.C.; Flück, D.; Dandanell, S.; Kirk, N.; Kaech, A.; et al. Exercise training increases skeletal muscle mitochondrial volume density by enlargement of existing mitochondria and not de novo biogenesis. Acta Physiol. 2018, 222, e12905.

- Essén-Gustavsson, B.; Tesch, P.A. Glycogen and triglyceride utilization in relation to muscle metabolic characteristics in men performing heavy-resistance exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1990, 61, 5–10.

- Koopman, R.; Manders, R.J.F.; Jonkers, R.A.M.; Hul, G.B.J.; Kuipers, H.; van Loon, L.J.C. Intramyocellular lipid and glycogen content are reduced following resistance exercise in untrained healthy males. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 96, 525–534.

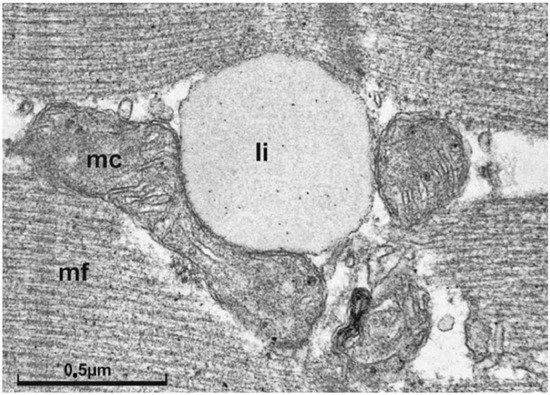

- van Loon, L.J.C.; Goodpaster, B.H. Increased intramuscular lipid storage in the insulin-resistant and endurance-trained state. Pflug. Arch. 2006, 451, 606–616.

- Hoppeler, H.; Howald, H.; Conley, K.; Lindstedt, S.L.; Claassen, H.; Vock, P.; Weibel, E.R. Endurance training in humans: Aerobic capacity and structure of skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 59, 320–327.

- Dubé, J.J.; Amati, F.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Toledo, F.G.S.; Sauers, S.E.; Goodpaster, B.H. Exercise-induced alterations in intramyocellular lipids and insulin resistance: The athlete’s paradox revisited. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 294, E882–E888.

- Bogardus, C.; Lillioja, S.; Stone, K.; Mott, D. Correlation between muscle glycogen synthase activity and in vivo insulin action in man. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 1185–1190.

- Ivy, J.L. Muscle glycogen synthesis before and after exercise. Sports Med. 1991, 11, 6–19.

- Acheson, K.J.; Schutz, Y.; Bessard, T.; Anantharaman, K.; Flatt, J.P.; Jéquier, E. Glycogen storage capacity and de novo lipogenesis during massive carbohydrate overfeeding in man. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1988, 48, 240–247.

- Ivy, J.L. Regulation of muscle glycogen repletion, muscle protein synthesis and repair following exercise. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2004, 3, 131–138.

- Stephens, F.B.; Tsintzas, K. Metabolic and molecular changes associated with the increased skeletal muscle insulin action 24–48 h after exercise in young and old humans. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 111–118.

- de Bock, K.; Richter, E.A.; Russell, A.P.; Eijnde, B.O.; Derave, W.; Ramaekers, M.; Koninckx, E.; Léger, B.; Verhaeghe, J.; Hespel, P. Exercise in the fasted state facilitates fibre type-specific intramyocellular lipid breakdown and stimulates glycogen resynthesis in humans. J. Physiol. 2005, 564, 649–660.

- Gaster, M.; Vach, W.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Schrøder, H.D. GLUT4 expression at the plasma membrane is related to fibre volume in human skeletal muscle fibres. APMIS 2002, 110, 611–619.

- Kirwan, J.P.; Del Aguila, L.F. Insulin signalling, exercise and cellular integrity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 1281–1285.

- King, D.S.; Feltmeyer, T.L.; Baldus, P.J.; Sharp, R.L.; Nespor, J. Effects of eccentric exercise on insulin secretion and action in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 75, 2151–2156.

- Flockhart, M.; Nilsson, L.C.; Tais, S.; Ekblom, B.; Apró, W.; Larsen, F.J. Excessive exercise training causes mitochondrial functional impairment and decreases glucose tolerance in healthy volunteers. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 957–970.e6.

- Egan, B.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 162–184.

- Hoffman, N.J.; Parker, B.L.; Chaudhuri, R.; Fisher-Wellman, K.H.; Kleinert, M.; Humphrey, S.J.; Yang, P.; Holliday, M.; Trefely, S.; Fazakerley, D.J.; et al. Global Phosphoproteomic Analysis of Human Skeletal Muscle Reveals a Network of Exercise-Regulated Kinases and AMPK Substrates. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 922–935.

- Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Newcomer, B.R.; Hunter, G.R. Influence of endurance running and recovery diet on intramyocellular lipid content in women: A 1H NMR study. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 282, E95–E106.

- Zderic, T.W.; Davidson, C.J.; Schenk, S.; Byerley, L.O.; Coyle, E.F. High-fat diet elevates resting intramuscular triglyceride concentration and whole-body lipolysis during exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 286, E217–E225.