Definition: This entry is addressing spiritual care in secular healthcare, where research has found that it can be challenging to incorporate spiritual care in daily practice, not least in post-secular, culturally entwined, and pluralist contexts. The aim of this integrative review was to locate, evaluate and discuss spiritual needs questionnaires from the post-secular perspective in relation to their applicability in secular healthcare. Eleven questionnaires were evaluated and discussed. This article offers an approach to the international exchange and implementation of knowledge, experiences, and best practice in relation to the use of spiritual needs assessment questionnaires in post-secular contexts.

- spiritual care

- religion

- spirituality

- secular

- post-secular

- spiritual needs

- assessment

- questionnaire

- Introduction

Research across healthcare contexts has shown that spiritual care can be of significant benefit to patients, in terms of increased quality of life, better mental health, and lowered levels of anxiety and depression [1–5]. It can be challenging, however, to incorporate spiritual care in daily practice [6-9]. Reasons for this include lack of training or time, uncertainty regarding how to deliver spiritual care, confusion about the concepts of ‘spirituality’ and ‘religion’, and the often-difficult reflexivity of one’s own sense of spirituality, religiosity, or lack thereof [7,10-12]. Furthermore, the culturally entwined and pluralist context of the world [13] makes it essential to understand the existential/spiritual/religious grounding of the individual patient, and from there to develop the best possible approach to providing spiritual care [14].

The growing international focus on the positive potential of religion and spirituality in relation to health can be argued to be an expression of the post-secular, understood here as the realization of the continued presence of the religious and spiritual in the public sphere and the attempt to negotiate this presence in culturally entwined and pluralist contexts [15-18]. In healthcare, the post-secular can be seen in the now widespread consensus among policymakers, researchers, practitioners, and patients that integrating spiritual care at all levels of healthcare is both beneficial and recommendable [10,19,20]. The literature is teeming with research aimed at developing qualified approaches to providing spiritual care [21-27].

Spiritual needs questionnaires arguably represent the most distributed intervention in relation to identifying spiritual needs [28]. However, the pluralist context makes it difficult to identify religious or spiritual needs through self-report questionnaires, because of the variance in spiritual and religious expression in any given context. Such variance can result in needs being reported predominantly on concepts relating to inner peace, generativity, and relatedness on personal levels, and to a lesser degree on religious and spiritual needs [29].

To address this situation, the aim of this integrative review was to identify spiritual needs questionnaires applicable in a post-secular context and to evaluate and discuss them from the post-secular perspective in relation to their applicability in secular healthcare.

Spiritual Care from a Post-Secular Perspective

This chapter elaborates on the understanding of the post-secular as outlined above. The post-secular is outlined from a macro perspective and from the perspective of the individual, as well as the understanding of the world as culturally entwined and pluralist. For the full elaboration see the full article, doi at the end of this entry.

[13,15-18,30–34]. The post-secular perspective allows for an understanding in which the presence of spiritual, religious, existential themes, thoughts, resources, and needs in the human being are recognized, appreciated, and brought into focus in the secular societal discourse of healthcare [35].

In our conceptualization of spiritual care, we focus on spiritual, religious, and existential orientations, needs, and resources in connection with life-threatening illness and crisis [33,34,36-38]. Following this, ‘Spiritual Care’ is understood as an overarching concept through which existential, spiritual, and religious needs can be identified and addressed appropriately [14]. At the same time, we acknowledge that these concepts are constructions, and that individuals do not easily render themselves to such constructions [39]. Consequently, they may mean different things in different contexts and to different individuals. For these exact reasons, there is no international consensus on the definition of spirituality [40-42]. From the post-secular perspective, the vernacular used to identify spiritual and religious needs must be carefully considered and evaluated in relation to both local context and individual patient. How the constructs ‘the existential’, ‘the religious’, and ‘the spiritual’ are related to each other and how individuals understand themselves as spiritual, religious or neither spiritual nor religious, presents a very complex discussion. In the present study, we employ a simple understanding of religion as referring to institutionalized religion and related activities, and spirituality as a primarily subjective construct relating to ultimate questions and the meaning of life [33,43,44,45]. However, to address spiritual needs in post-secular contexts, which are culturally entwined and pluralist, we argue that these definitions are secondary to the patients point of view, which must be the primary focus when providing qualified and appropriate spiritual care.

- Method

This integrative review is based on the methodological approach suggested by Whittemore and Knafl [46][47].

For reasons of comprising the length of this entry in Encyclopedia.pub we have excluded the remainder of this chapter. For the full version please refer to the full article, doi at the end of the entry. However, we have kept the flow chart (Figure 1) and the criteria for inclusion (Table 1).

Table 1. Criteria for inclusion.

|

Inclusion: The Instrument Had to Be (Listed Alphabetically) |

|

A spiritual needs assessment questionnaire or applicable as such |

|

Applicable as a self-report questionnaire |

|

Any of the following target groups: chronic disease patients, life-threatening illness, or terminal patients (end-of-life) |

|

Deemed applicable in a post-secular context, by initial face validation |

|

Published in a peer-review journal |

|

Written in English |

- Results

Table 2 lists the 11 included questionnaires alphabetically and includes author, contextual origin, year of publication, primary health field, the Likert scale, and the number of questions included.

Table 2. Questionnaires.

|

Instrument Name Abbreviation |

Author, Origin Year |

Health Field |

Likert Scale |

Number of Questions |

|

Existential Distress Scale EDS |

Lo et al. Canada 2017 [51] |

Cancer |

5 |

10 |

|

(Portuguese) End of Life Spiritual Comfort Questionnaire EOLSCQ |

Pinto et al. Portugal 2016 [52] |

EOL/PC |

6 |

28 |

|

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy —Spiritual Well-Being Scale FACIT-Sp-12 |

Peterman et al. USA 2002 [53] |

Cancer—Chronic illness |

5 |

12 |

|

Holistic Health Status Questionnaire HHSQ |

Chan et al., Hong Kong 2016 [54] |

Chronic illness |

4 |

45 |

|

Meaning in Life Scale MiLS |

Jim et al. USA 2006 [55] |

Cancer |

6/4 |

21 |

|

Patient Dignity Inventory PDI |

Chochinov et al. Canada 2008 [56] |

EOL/PC |

5 |

25 |

|

Patient Spiritual Needs Assessment Scale PSNAS |

Galek et al. USA 2005 [57] |

EOL/PC |

6 |

29 |

|

QE Health Scale QEHS |

Faull & Hill, New Zealand 2007 [58] |

Chronic physical disabilities |

5 |

28 |

|

Quality of Life Questionnaire—Spiritual Wellbeing—32 QLQ-SWB–32 |

Vivat et al. EU 2017 [59] |

EOL/PC |

4/8 |

32 |

|

Spiritual Needs Questionnaire for Palliative Care SNQPC |

Vilalta et al. Spain 2014 [60] |

Cancer/PC |

5 |

28 |

|

Spiritual Needs Questionnaire SpNQ |

Büssing et al, Germany 2010 [61] |

Cancer—Chronic illness |

Y/N/3 |

27 |

- Inductive, Taxonomic Analysis, and Measurement Properties

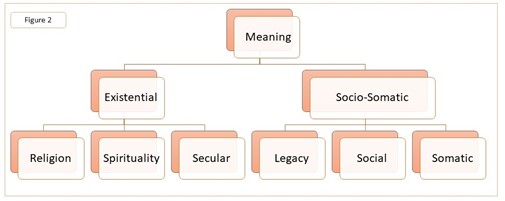

Figure 2 shows the result of the inductive and taxonomic analyses, including six established categories, under two subdomains and under one domain.

Figure 2. Inductive and taxonomic analyses.

The analyses established six categories. The categories ‘Religion’ and ‘Spirituality’ pertained to words that the author group agreed in plenum belonged to either a religious or a spiritual vernacular.

The category ‘Secular’ contains questions oriented towards existential topics and formulated in a secular vernacular. The ‘Legacy’ category contains questions oriented towards being remembered, having unfinished business, contribution to life, etc. The ‘Social’ category contains questions oriented towards social activities with family and friends. The ‘Somatic’ category contains questions oriented towards physical aspects in relation to illness, including questions directed to the healthcare professionals (HCP).

On the basis of these six categories, the taxonomic analysis established the sub-domains ‘Existential’ and ‘Socio-Somatic’ under the main domain ‘Meaning’, given that all the questions can be characterized as meaning-oriented, whether oriented towards making meaning in relation to religious, spiritual, existential, social, or somatic issues.

Table 3: ‘List of religious or spiritual words used in the included questionnaires’; Table 4: ‘Existential and socio-somatic sub-domains’; Table 5: ‘Clinimetric properties self-reported in primary articles’; and Table 6 ‘Secular applicability’ have been excluded from this entry. To view the tables please refer to the full article, see doi at the end of the entry.

5. Discussion: Evaluation of Applicability in a Post-Secular Context

For the full discussion please see the article, see doi at the end of this entry.

It is imperative to note that the following evaluation is not to be considered as a final or conclusive evaluation as to whether any one of the questionnaires can be used in any given context. This is a general discussion that considers (some) of the topics that should be taken into account when implementing a spiritual-needs assessment questionnaire, viewed in relation to the post-secular perspective. It is for practitioners in local contexts to evaluate the extent to which a questionnaire, or part of a questionnaire, is applicable in the specific context and in relation to the particular patient in question [14].

It can be argued that all the included questionnaires represent examples of the post-secular in healthcare, as they assess patients’ spiritual, religious, and existential needs. Their use reflects an appreciation of the importance of addressing such needs in relation to patient health, while also, to varying degrees, contemplating the post-secular perspective of a culturally entwined and pluralist context.

The contextual origin of a questionnaire will of course influence the way it is formulated and may explain why certain RS wording is used that refers to specific religious or spiritual orientations, while other religious or spiritual orientations are not referred to. The SNQPC, for instance, originated in Spain [60], where the predominant religious background is Catholicism. In 2017, 70.5% of the Spanish population considered themselves to be Catholic [64]. This is reflected in the SNQPC in the formulation of the RS wording, with questions such as “Do you see your illness as a form of divine punishment or as a punishment for your life in general?”, or “Do you believe that God can intervene to cure a serious illness?”. However, Spain is also a culturally entwined and pluralist context, with a secular state established in 1978 [64]. This raises questions about the dominant cultural background being based in a specific religious orientation. Where does this leave the pluralist condition, where the number of patients adhering to other religious, spiritual, or existential orientations can be expected to increase? [13]. Furthermore, ethical questions need to be considered when using a question formulated as the above two examples, as to how the patient might be impacted by being asked such a question. A further reflection with respect to differences between the contextual origin of a spiritual needs questionnaire is whether the formulation of the questions reflects constitutional differences regarding the pluralist condition. The pluralist condition, as formulated in the First Amendment of the US Constitution, where equality between religious denominations is ensured by preventing the state from creating or favoring a religion [65], differs significantly from the pluralist condition as formulated in many European contexts, where a national church often holds a favored position in the constitution but also in relation to identification and tradition in the general population [14]. The Constitutional Act of Denmark, for instance, states that the established church of Denmark is the Evangelical Lutheran Church and shall as such be supported by the state (§4) [8].

It is not feasible to refer to and include all religious and spiritual orientations; however, from the post-secular perspective, this raises the following question: when all religious or spiritual orientations cannot be mentioned, why mention even one? In culturally entwined and pluralist contexts, spiritual needs questionnaires should consider including, instead of excluding, religious, spiritual, and secular existential orientations. These are complex considerations that highlight the importance of the local context to explicitly contemplate the cultural and pluralist complexity of the context and of the (patient) population.

The HHSQ, which is from Hong Kong, is the only questionnaire that refers to religious traditions from both monotheistic religions and the religious orientations employing the concept of Karma. This may reflect an approach to the pluralist context in Hong Kong. The QEHS (New Zealand) was developed as a holistic measure whereby the existential, spiritual, and somatic aspects are seen as integrated. This holistic integration of the spiritual and somatic brings attention to the limitations of the constructs we employ and how human beings do not necessarily comply with these constructs [39,66,67].

In considering whether a spiritual-needs questionnaire with minimal RS wording suffices in identifying spiritual needs, the question arises as to whether HCPs can successfully identify religious or spiritual needs on the basis of the questionnaire. Using questionnaires with a primarily neutral RS wording can reach a wider patient population. However, this leaves the responsibility of identifying religious or spiritual needs to the HCP. Whether the involved HCPs are adequately trained in evaluating and identifying spiritual needs should be considered, as well as what the appropriate interventions might be, and how to proceed in developing a spiritual care treatment plan that appropriately and ethically addresses the specific needs [14]. The importance of training and educational programs in spiritual care is stressed as important in the literature, and many contexts have now implemented spiritual care in the curriculum and training has been developed for providing spiritual care [68–71]. However, research also stresses that spiritual care is often left to ad hoc or arbitrary solutions and linked to personal values [72,73].

In examining questionnaires that include RS wording that is not neutral, we argue that a consensual understanding of RS wording needs to be established between patient and HCP. The RS wording ‘spirituality’ may serve as an example. We classify spirituality as neutral RS wording because it does not refer to a specific spiritual orientation. However, and as mentioned earlier, spirituality (and through that spiritual care) is an ambiguous term because it is a construct that lacks consensus with regard to its definition, in both local and international contexts [37,42,74]. In one context, a common consensus on what the word entails may have been developed, while in other contexts it may be an immature concept [40,41]. Whether the patient and HCP can be expected to have a shared understanding on the meaning of RS wording needs to be evaluated. In pluralist settings, it might be challenging to reach a consensus on wording. The use of non-neutral RS wording may assist in developing a dialogue between patient and HCP in the attempt to reach a consensual understanding and thereby identify needs [75]. The consideration of the culturally entwined context has been identified as central in research [76,77]. However, the process of translation does not necessarily account for the importance of a consensual understanding of RS wording. We argue this to be imperative, if spiritual care questionnaires are to be employed in post-secular contexts that have different local understandings of RS wording.

Secular-formulated questions can identify existential needs. However, whether they are able to identify religious or spiritual needs will depend on whether the HCP identifies that religious or spiritual needs may be at the root of the answers given by a patient, and therefore requires further clarification, as argued above. In relation to including somatic questions with existential, religious, or spiritual questions, this should be considered from an ethical perspective, as to whether it is appropriate to have questions pertaining to, for instance, personal hygiene, next to existential, religious, and spiritual questions. The HHSQ provides 45 questions with 21 in the socio-somatic domain and 24 in the existential domain. This reflects the fact that the HHSQ is a holistic health assessment questionnaire. This leads to considerations of how many questions are needed and how many questions the patient is capable of answering. This point has to be seen in relation to the diagnosis and health situation of the patient, which also includes considerations about the healthcare field in which the questionnaire has been developed. The questionnaires included in this review are focused on end-of-life, palliative care, cancer, and chronic illness (Table 2). Only the local context can evaluate these considerations, bearing in mind that it is the complete, holistic, well-being of the patient that lies at the heart of healthcare.

- Conclusions

In conclusion, this integrative review has focused on identifying spiritual needs questionnaires that could be applicable in secular healthcare in post-secular contexts. Eleven questionnaires were included for evaluation, which was conducted on the basis of inductive and taxonomic analyses. The evaluation and discussion focused on the religious and spiritual words used in the questionnaires, highlighting various topics that need to be addressed when evaluating the applicability of a spiritual needs questionnaire in a post-secular context.

The evaluation focused on factors to be considered when implementing a spiritual needs questionnaire in a post-secular context, mainly the pluralist condition, the use of RS wording, and a reflection on the originating context.

The findings provide a perspective for healthcare fields in which spiritual needs questionnaires are to be translated from a different cultural context. By highlighting some of the factors that should be taken into consideration, this article can act as a general guideline for local contexts when developing approaches to identifying spiritual needs and providing spiritual care that is applicable in daily practice.

From these perspectives, this article offers an approach to the international exchange and implementation of knowledge, experiences, and best practice in relation to the use of spiritual needs assessment questionnaires in post-secular contexts.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, N.C.H. and R.D.N.; methodology, R.D.N. and N.C.H.; formal analysis, R.D.N., E.F. and T.K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.N.; writing—review and editing, E.F., T.K.S. and N.C.H.; supervision, N.C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: The work was funded by an unrestricted grant from Pfizer Oncology Denmark.

Data Availability Statement: This study did not include data.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph182412898

References

- Tan, H.; Rumbold, B.; Gardner, F.; Snowden, A.; Glenister, D.; Forest, A.; Bossie, C.; Wyles, L. Understanding the outcomes of spiritual care as experienced by patients. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2020, 10, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2020.1793095.

- Chen, J.; Lin, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y.; Hu, R. The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1167–1179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318772267.

- Vallurupalli, M.; Lauderdale, K.; Balboni, M.J.; Phelps, A.C.; Block, S.D.; Ng, A.K.; Kachnic, L.A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Balboni, T.A. The Role of Spirituality and Religious Coping in the Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Cancer Receiving Palli-ative Radiation Therapy. J. Support. Oncol. 2012, 10, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.003.

- Balboni, T.A.; Paulk, M.E.; Balboni, M.J.; Phelps, A.C.; Loggers, E.T.; Wright, A.A.; Block, S.D.; Lewis, E.F.; Peteet, J.R.; Prigerson, H.G. Provision of Spiritual Care to Patients With Advanced Cancer: Associations with Medical Care and Quality of Life Near Death. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.24.8005.

- Büssing, A. (Ed.) Spiritual Needs in Research and Practice; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70139-0.

- Andersen, A.H.; Hvidt, E.A.; Hvidt, N.C.; Roessler, K.K. ‘Maybe we are losing sight of the human dimension’–physicians’ approaches to existential, spiritual, and religious needs among patients with chronic pain or multiple sclerosis. A qualitative interview-study. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2020, 8, 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2020.1792308.

- Best, M.; Butow, P.; Olver, I. Why do We Find It so Hard to Discuss Spirituality? A Qualitative Exploration of Attitudinal Barriers. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm5090077.

- Nissen, R.D.; Gildberg, F.A.; Hvidt, N.C. Approaching the religious psychiatric patient in a secular country: Does “subal-ternalizing” religious patients mean they do not exist? Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2019, 41, 123–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0084672419868770.

- Hammoudeh, L.; Balboni. T. Physician’s Perspectives on Addressing Patients’ Spiritual Needs. In Spiritual Needs in Research and Practice; Büssing, A., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70139-0_31.

- Jones, K.F.; Paal, P.; Symons, X.; Best, M.C. The Content, Teaching Methods and Effectiveness of Spiritual Care Training for Healthcare Professionals: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e261–e278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.03.013.

- Balboni, M.J.; Sullivan, A.; Enzinger, A.C.; Epstein-Peterson, Z.D.; Tseng, Y.D.; Mitchell, C.; Niska, J.; Zollfrank, A.; VanderWeele, T.J.; Balboni, T.A. Nurse and Physician Barriers to Spiritual Care Provision at the End of Life. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 400–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.09.020.

- Bar-Sela, G.; Schultz, M.J.; Elshamy, K.; Rassouli, M.; Ben-Arye, E.; Doumit, M.; Gafer, N.; Albashayreh, A.; Ghrayeb, I.; Turker, I.; et al. Training for awareness of one’s own spirituality: A key factor in overcoming barriers to the provision of spiritual care to advanced cancer patients by doctors and nurses. Palliat. Support. Care 2019, 17, 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1017/s147895151800055x.

- Berger, P.L. The Many Altars of Modernity; De Gruyter: Boston, MA, USA; Berlin, Germany, 2014.

- Nissen, R.D.; Viftrup, D.T.; Hvidt, N.C. The Process of Spiritual Care. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 674453. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.674453.

- Habermas, J. Notes on Post-Secular Society. New Perspect. Q. 2008, 25, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5842.2008.01017.x.

- Gorski, P.; Kim, D.K.; Torpey, J.; VanAntwerpen, J. The Post-Secular in Question: Religion in Contemporary Society; NYU Press: New York, USA, 2012.

- Nynäs, P.; Lassander, M.; Utriainen, T. (Eds.) Post-Secular Society, 1st ed.; Transaction Publishers: New Brunswick, USA, 2012; https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315127095.

- Berger, P.L. The Hospital: On the Interface Between Secularity and Religion. Society 2015, 52, 410–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-015-9941-z.

- Puchalski, C.; Ferrell, B.; Virani, R.; Otis-Green, S.; Baird, P.; Bull, J.; Chochinov, H.; Handzo, G.; Nelson-Becker, H.; Prince-Paul, M.; et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J. Palliat. Med. 2009, 12, 885–904.

- World Health Organization Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Integrated Treatment throughout the Life Course. J. Pain Palliat. Care Pharmacother. 2014, 28, 130–134. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2014.911801.

- Gijsberts, M.H.E.; van der Steen, J.T.; Hertogh, C.; Deliens, L. Spiritual care provided by nursing home physicians: A na-tionwide survey. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2019, 10, e42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001756.

- Harrad, R.; Cosentino, C.; Keasley, R.; Sulla, F. Spiritual care in nursing: An overview of the measures used to assess spiritual care provision and related factors amongst nurses. Acta Biomed 2019, 90, 44–55.

- Drummond, D.A.; Carey, L.B. Assessing Spiritual Well-Being in Residential Aged Care: An Exploratory Review. J. Relig. Health 2018, 58, 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0717-9.

- Seddigh, R.; Keshavarz-Akhlaghi, A.-A.; Azarnik, S. Questionnaires Measuring Patients’ Spiritual Needs: A Narrative Lit-erature Review. Iran J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2016, 10, e4011. https://doi.org/10.17795/ijpbs-4011.

- Lucchetti, G.; Bassi, R.M.; Lucchetti, A.L.G. Taking Spiritual History in Clinical Practice: A Systematic Review of Instruments. Explor. 2013, 9, 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2013.02.004.

- Ghorbani, M.; Mohammadi, E.; Aghabozorgi, R.; Ramezani, M. Spiritual care interventions in nursing: An integrative liter-ature review. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1165–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05747-9.

- Büssing, A. The Spiritual Needs Questionnaire in Research and Clinical Application: A Summary of Findings. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 3732–3748. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01421-4.

- Damberg Nissen, R.; Falkø, E.; Toudal Viftrup, D.; Assing Hvidt, E.; Søndergaard, J.; Büssing, A.; Wallin, J.A.; Hvidt, N.C. The Catalogue of Spiritual Care Instruments: A Scoping Review. Religions 2020, 11, 252.

- Büssing, A.; Janko, A.; Baumann, K.; Hvidt, N.C.; Kopf, A. Spiritual Needs among Patients with Chronic Pain Diseases and Cancer Living in a Secular Society. Pain Med. 2013, 14, 1362–1373. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12198.

- Casanova, J. Are We Still Secular? Explorations on the Secular and the Post-Secular. In Post-Secular Society; Nynäs, P., Las-sander, M., Utriainen, T., Eds.; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012.

- Beaumont, J.; Eder, K.; Mendieta, E. Reflexive secularization? Concepts, processes and antagonisms of postsecularity. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2018, 23, 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431018813769.

- Casanova, J.; van den Breemer, R.; Wyller, T. Secular and Sacred: The Scandinavian Case of Religion in Human Rights, Law and Public Space; Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht: Göttingen, Germany, 2014.

- la Cour, P.; Hvidt, N.C. Research on meaning-making and health in secular society: Secular, spiritual and religious existential orientations. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1292–1299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.06.024.

- Hvidt, N.C.; Assing Hvidt, E.; la Cour, P. Meanings of "the existential" in a Secular Country: A Survey Study. J. Relig. Health 2021, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01253-2.

- Nissen, R.D. Andersen, A. Addressing Religion in Secular Healthcare: Existential communication and the post-secular negotiation. Religions, id. No. religions-1489718. Forthcoming.

- Nolan, S. 2011, Spiritual care in palliative care—Working towards an EAPC Task Force. European Journal of Palliative Care, 18(2).

- Hvidt, N.C.; Nielsen, K.T.; Kørup, A.K.; Prinds, C.; Hansen, D.G.; Viftrup, D.T.; Hvidt, E.A.; Hammer, E.R.; Falkø, E.; Locher, F.; et al. What is spiritual care? Professional perspectives on the concept of spiritual care identified through group concept mapping. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042142. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042142.

- Ramezani, M.; Ahmadi, F.; Mohammadi, E.; Kazemnejad, A. Spiritual care in nursing: A concept analysis. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2014, 61, 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12099.

- Descola, P. Beyond Nature and Culture; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2014.

- Koenig, H.G. Concerns About Measuring “Spirituality” in Research. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2008, 196, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0b013e31816ff796.

- Grabenweger, R.; Paal, P. Spiritualität in der psychiatrischen Pflege—Begriffsanalyse und Vorschlag einer Arbeitsdefinition. Spirit. Care 2021, 10, 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1515/spircare-2019-0131.

- Saad, M.; de Medeiros, R. Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications. Religions 2021, 12, 22.

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I.; Cole, B.; Rye, M.S.; Butter, E.M.; Belavich, T.G.; Hipp, K.M.; Scott, A.B.; Kadar, J.L. Religion and Spirituality: Unfuzzying the Fuzzy. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1997, 36, 549. https://doi.org/10.2307/1387689.

- Huguelet, P.; Koenig, H.G. Religion and Spirituality in Psychiatry; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009;. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511576843

- Bash, A. Spirituality: The emperor’s new clothes? J. Clin. Nurs. 2004, 13, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00838.x.

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005, Dec). The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs, 52(5), 546-553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- De Souza, M.T.; Da Silva, M.D.; De Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein (São Paulo) 2010, 8, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082010rw1134.

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748.

- Gildberg, F.A.; Bradley, S.K.; Tingleff, E.B.; Hounsgaard, L. Empirically Testing Thematic Analysis (ETTA): Methodological implications in textual analysis coding system. Nord. Sygeplejeforskning 2015, 5, 193–207.

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. 2006. Sage Publications, London, UK. ISBN. 13-978-0-76-19-7353-9.

- Lo, C., Panday, T., Zeppieri, J., Rydall, A., Murphy-Kane, P., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2017, Nov). Preliminary psy-chometrics of the Existential Distress Scale in patients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl), 26(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12597

- Pinto, S.M.O.; Berenguer, S.M.A.C.; Martins, J.C.A.; Kolcaba, K. Cultural adaptation and validation of the Portuguese End of Life Spiritual Comfort Questionnaire in Palliative Care patients. Porto Biomed. J. 2016, 1, 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbj.2016.08.003.

- Peterman, A.H.; Fitchett, G.; Brady, M.J.; Hernandez, L.; Cella, D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2401_06.

- Chan, C.W.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Yeung, S.M.; Sum, F. Holistic Health Status Questionnaire: Developing a measure from a Hong Kong Chinese population. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0416-8.

- Jim, H.S.; Purnell, J.; Richardson, S.A.; Golden-Kreutz, D.; Andersen, B.L. Measuring meaning in life following cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 1355–1371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-006-0028-6.

- Chochinov, H.M.; Hassard, T.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Harlos, M.; Sinclair, S.; Murray, A. The Patient Dignity Inventory: A Novel Way of Measuring Dignity-Related Distress in Palliative Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2008, 36, 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018.

- Galek, K.; Flannelly, K.J.; Vane, A.; Galek, R.M. Assessing a Patientʼs Spiritual Needs: A comprehensive instrument. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2005, 19, 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004650-200503000-00006.

- Faull, K.; Hills, M.D. A spiritually-based measure of holistic health for those with disabilities: Development, preliminary reliability and validity assessment. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 999–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280600926637.

- Vivat, B.; Young, T.; Winstanley, J.; Arraras, J.; Black, K.; Boyle, F.; Bredart, A.; Costantini, A.; Guo, J.; Irarrazaval, M.; et al. The international phase 4 validation study of the EORTC QLQ-SWB32: A stand-alone measure of spiritual well-being for people receiving palliative care for cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12697. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12697.

- Vilalta, A.; Valls, J.; Porta, J.; Viñas, J. Evaluation of Spiritual Needs of Patients with Advanced Cancer in a Palliative Care Unit. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 592–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0569.

- Büssing, A.; Balzat, H.-J.; Heusser, P. Spiritual needs of patients with chronic pain diseases and cancer—Validation of the spiritual needs questionnaire. Eur. J. Med Res. 2010, 15, 266–273. https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-783x-15-6-266.

- Mokkink, L.B.; De Vet, H.C.W.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist for systematic reviews of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 1171–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1765-4.

- Brintz, C.E.; Birnbaum-Weitzman, O.; Merz, E.L.; Penedo, F.J.; Daviglus, M.L.; Fortmann, A.L.; Gallo, L.C.; Gonzalez, P.; Johnson, T.P.; Navas-Nacher, E.L.; et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being-expanded (FACIT-Sp-Ex) across English and Spanish-speaking Hispanics/Latinos: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychol. Relig. Spirit. 2017, 9, 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000071.

- Fuente-Cobo, C.; Carabante-Muntada, J.M. Media and Religion in Spain: A Review of Major Trends. J. Relig. Media Digit. Cult. 2018, 7, 175–202. https://doi.org/10.1163/21659214-00702003.

- Administration USNAaR. National Archives. 2021. Availabe online: https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Holbraad, M.; Pedersen, M.A. The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316218907.

- Nelson-Becker, H.; Moeke-Maxwell, T. Spiritual Diversity, Spiritual Assessment, and Māori End-of-Life Perspectives: At-taining Ka Ea. Religions 2020, 11, 536. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11100536.

- Bandini, J.; Thiel, M.; Meyer, E.; Paasche-Orlow, S.; Zhang, Q.; Cadge, W. Interprofessional spiritual care training for geriatric care providers. Innov. Aging 2018, 2, 963. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy031.3569.

- Puchalski, C.; Jafari, N.; Buller, H.; Haythorn, T.; Jacobs, C.; Ferrell, B. Interprofessional Spiritual Care Education Curriculum: A Milestone toward the Provision of Spiritual Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 777–784. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0375.

- Attard, J.; Baldacchino, D.R.; Camilleri, L. Nurses’ and midwives’ acquisition of competency in spiritual care: A focus on education. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, 1460–1466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.04.015.

- Viftrup, D.T.; Laursen, K.; Hvidt, N.C. Developing an Educational Course in Spiritual Care: An Action Research Study at Two Danish Hospices. Religions 2021, 12, 827. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12100827.

- Moestrup, L.; Hvidt, N.C. Where is God in my dying? A qualitative investigation of faith reflections among hospice patients in a secularized society. Death Stud. 2016, 40, 618–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2016.1200160.

- Austin, P.; Macdonald, J.; MacLeod, R. Measuring Spirituality and Religiosity in Clinical Settings: A Scoping Review of Available Instruments. Religions 2018, 9, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030070.

- Timmins, F.; Murphy, M.; Caldeira, S.; Ging, E.; King, C.; Brady, V.; Whelan, J.; O’Boyle, C.; Kelly, J.; Neill, F.; et al. De-veloping Agreed and Accepted Understandings of Spirituality and Spiritual Care Concepts among Members of an Innovative Spirituality Interest Group in the Republic of Ireland. Religions 2016, 7, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel7030030.

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

- Willis, G.B. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2005. ISBN-13: 978-0761928041

- Forsyth, B.H.; Kudela, M.S.; Levin, K.; Lawrence, D.; Willis, G.B. Methods for Translating an English-Language Survey Questionnaire on Tobacco Use into Mandarin, Cantonese, Korean, and Vietnamese. Field Methods 2007, 19, 264–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x07302105.