Fish gut represents a peculiar ecological niche where bacteria can transit and reside to play vital roles by producing bio-compounds with nutritional, immunomodulatory and other functions. This complex microbial ecosystem reflects several factors (environment, feeding regimen, fish species etc.). The objective of the present study was the identification of intestinal microbial strains able to produce molecules called biosurfactants (BSs) which were tested for surface and antibacterial activity in order to select a group of probiotic bacteria for aquaculture use. This works indicated that fish gut is a source of bioactive compounds which deserves to be explored for applicative purposes.

- grey mullets

- natural antibiotics

- gut microbiota

- probiotics

1. Enumeration of Bacteria and Colony Isolation

2. Screening of Bacteria for BS Production

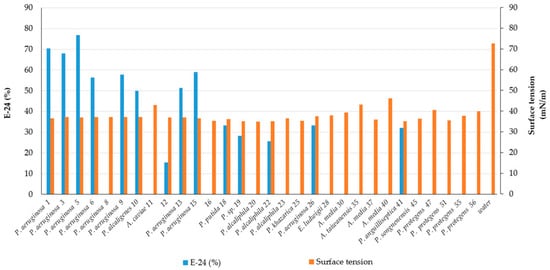

| Strain | Fish Species |

Bacterial Affiliation |

GeneBank Accession Number |

Drop Collapse | E-24 (%) |

Surface TensionmN·m−1 |

BS Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MW369461 | +++ | 70.5 ± 9.1 | 36.5 ± 0.1 | Rhamnolipid |

| 3 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | OK342256 | +++ | 68.0 ± 12.7 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | Rhamnolipid |

| 5 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | OK342257 | +++ | 77.0 ± 0.0 | 36.9 ± 0.4 | Rhamnolipid |

| 6 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MW369462 | +++ | 56.4 ± 0.0 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | Less polar compound |

| 8 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | OK342258 | ++ | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 9 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | OK342259 | +++ | 57.7 ± 1.8 | 37.2 ± 0.3 | nd |

| 10 | CR | Pseudomonas alcaligenes | MW369463 | + | 50.0 ± 1.8 | 37.2 ± 0.3 | nd |

| 11 | CR | Aeromonas caviae | MW369464 | - | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 43.0 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 12 | CR | - | - | +++ | 15.4 ± 21.8 | 36.9 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 13 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MW369465 | +++ | 51.3 ± 3.6 | 36.9 ± 0.1 | Rhamnolipid |

| 15 | CR | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MW369466 | +++ | 59.0 ± 3.6 | 36.6 ± 0.6 | Rhamnolipid |

| 16 | CR | - | - | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 35.35 ± 0.6 | nd |

| 17 | CR | Pseudomonas mendocina | MW369467 | - | 20.5 ± 0 | nd | nd |

| 18 | CR | Pseudomonas putida | OK342260 | weak | 33.3 ± 3.6 | 36.1 ± 0.1 | Less polar compound |

| 19 | MC | Pseudomonas sp. | OK342261 | + | 28.2 ± 3.6 | 35.2 ± 0.0 | Less polar compound |

| 20 | MC | Pseudomonas alcaliphila | MW369468 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 35.0 ± 0.4 | nd |

| 21 | MC | - | - | weak | 25.6 ± 14.5 | nd | nd |

| 22 | MC | Pseudomonas sp. | OK342262 | + | 25.6 ± 0.0 | 35.1 ± 0.2 | Less polar compound |

| 23 | MC | Pseudomonas sp. | OK342263 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 36.5 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 24 | MC | Pseudomonas khazarica | MW369469 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | nd | nd |

| 25 | MC | Pseudomonas sp. | OK342264 | + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 35.3 ± 0.1 | Less polar compounds |

| 26 | MC | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MW369470 | ++ | 33.3 ± 0.0 | 37.6 ± 0.3 | Less polar compound |

| 28 | CS | Enterobacter ludwigii | MW369471 | + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 37.9 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 30 | CS | Aeromonas media | MW369472 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 39.4 ± 0.9 | nd |

| 35 | CS | Aeromonas taiwanensis | MW369473 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 43.2 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 37 | CL | Aeromonas media | MW369474 | - | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 35.9 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 40 | CL | Aeromonas media | MW369476 | - | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 46.1 ± 0.3 | nd |

| 41 | CL | Pseudomonas anguilliseptica | MW369477 | + | 32.1 ± 5.4 | 35.2 ± 0.6 | nd |

| 45 | CL | Pseudomonas stutzeri | OK342265 | + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 36.3 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 47 | CL | Pseudomonas protegens | MW369478 | weak | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 40.5 ± 0.4 | nd |

| 51 | CL | Pseudomonas protegens | OK342266 | + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 35.5 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 55 | CL | Pseudomonas protegens | MW369480 | - | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 37.7 ± 0.1 | nd |

| 56 | CL | Pseudomonas sp. | OK342267 | + | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 39.9 ± 0.1 | nd |

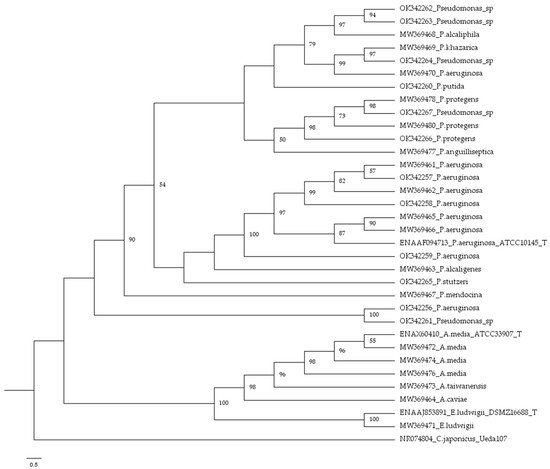

3. Bacterial Identification

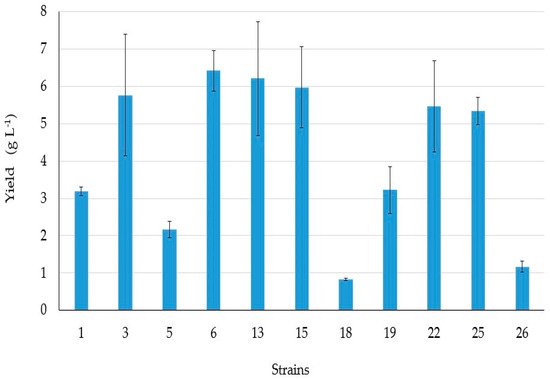

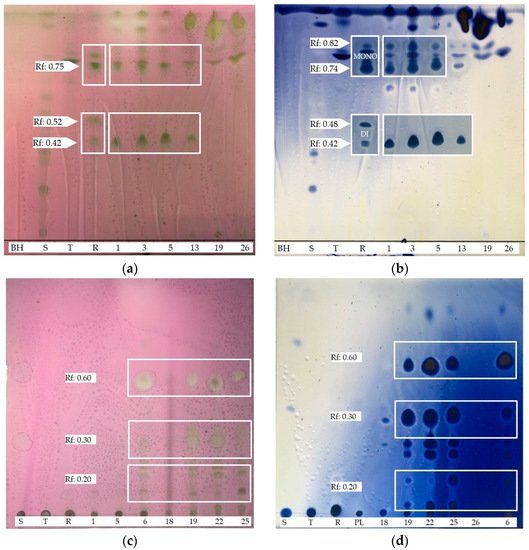

4. BSs yield and Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC)

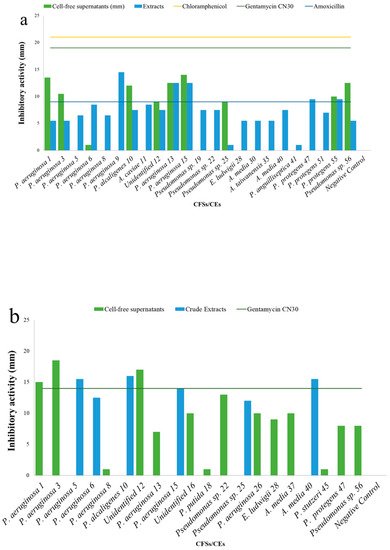

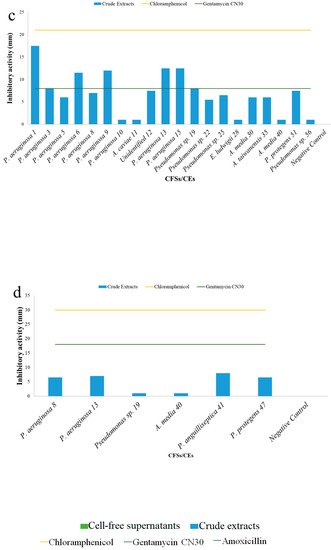

5. Antibacterial Activities

| Cell-Free Supernatants (CFSs) and Crude Extracts (CEs) (mm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | S. aureus H1610 | P. mirabilis H1643 | K. pneumoniae H1637 | A. hydrophila H1563 | ||||

| CFSs | CEs | CFSs | CEs | CFSs | CEs | CFSs | CEs | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 1 | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 15 ± 0.0 | - | - | 17.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3 | 10.5 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 18.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | 8.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 5 | - | 5.5 ± 0.7 | - | 15.5 ± 0.7 | - | 6.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6 | + | 8.5 ± 0.7 | - | 12.5 ± 0.7 | - | 11.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 8 | - | 6.5 ± 0.7 | + | - | - | 7.0 ± 0.0 | - | 6.5 ± 0.7 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 9 | - | 14.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | 12.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas alcaligenes 10 | 12 ± 0.0 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | - | 16.0 ± 0.0 | - | + | - | - |

| Aeromonas caviae 11 | - | 8.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | + | - | - |

| Unidentified 12 | 9 ± 1.4 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 17.0 ± 1.4 | - | - | 7.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 13 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | 12.5 ± 0.7 | - | 7.0 ± 0.0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 15 | 14 ± 0.0 | 12.5 ± 0.7 | - | 14.0 ± 0.0 | - | 12.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Unidentified 16 | - | - | 10.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas putida 18 | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas sp. 19 | - | 7.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | 8.0 ± 0.0 | - | + |

| Pseudomonas alcaliphila 20 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas sp. 22 | - | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 13.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | 5.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas sp. 23 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas sp. 25 | 9 ± 0.0 | + | - | 12.0 ± 0.0 | - | 6.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 26 | - | - | 10 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Enterococcus ludwigii 28 | - | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.0 | - | + | + | - | - |

| Aeromonas media 30 | - | 5.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | 6.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| Aeromonas taiwanensis 35 | - | 5.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | 6.0 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas protegens 37 | - | - | 10.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Aeromonas media 40 | - | 7.5 ± 0.7 | - | 15.5 ± 0.7 | - | + | - | + |

| Pseudomonas anguilliseptica 41 | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | 8.0 ± 0.0 |

| Pseudomonas stutzeri 45 | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas protegens 47 | - | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | - | 6.5 ± 0.7 |

| Pseudomonas protegens 51 | - | 7.0 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | 7.5 ± 0.7 | - | - |

| Pseudomonas protegens 55 | 10 ± 0.0 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pseudomonas sp. 56 | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 8.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | + | - | - |

| Negative control | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | ||||

| Chloramphenicol | 21 ± 0.0 | - | + | 30.0 ± 0.0 | ||||

| Gentamycin CN30 | - | 14 | 8.0 ± 0.0 | 18.0 ± 0.0 | ||||

| Amoxycillin | - | - | - | - | ||||

[1]

[1]

6. Conclusions

The present research let to select bacterial strains from the gut of grey mullets with interesting biotechnologically traits and has confirmed that intestinal microbiota is a promising source of new and biologically active pharmaceutical agents to control fish health and to preserve the environment. Additionally, the study of BS-producing bacteria associated with fish intestine is of relevance for our understanding of their ecological role in the symbiotic and antagonist interaction with the host and between themselves and for understanding whether the production of bioactive compounds might represent a biological strategy for protecting fish against gut and liver inflammations, an immune response and for survival with respect to the surrounding environmentThis entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9122555

References

- Bodour, A.A.; Drees, K.P.; Maier R.M.; Distribution of biosurfactant-producing bacteria in undisturbed contaminated arid southwestern soils. . Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3280-3287, 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3280-3287.2003.