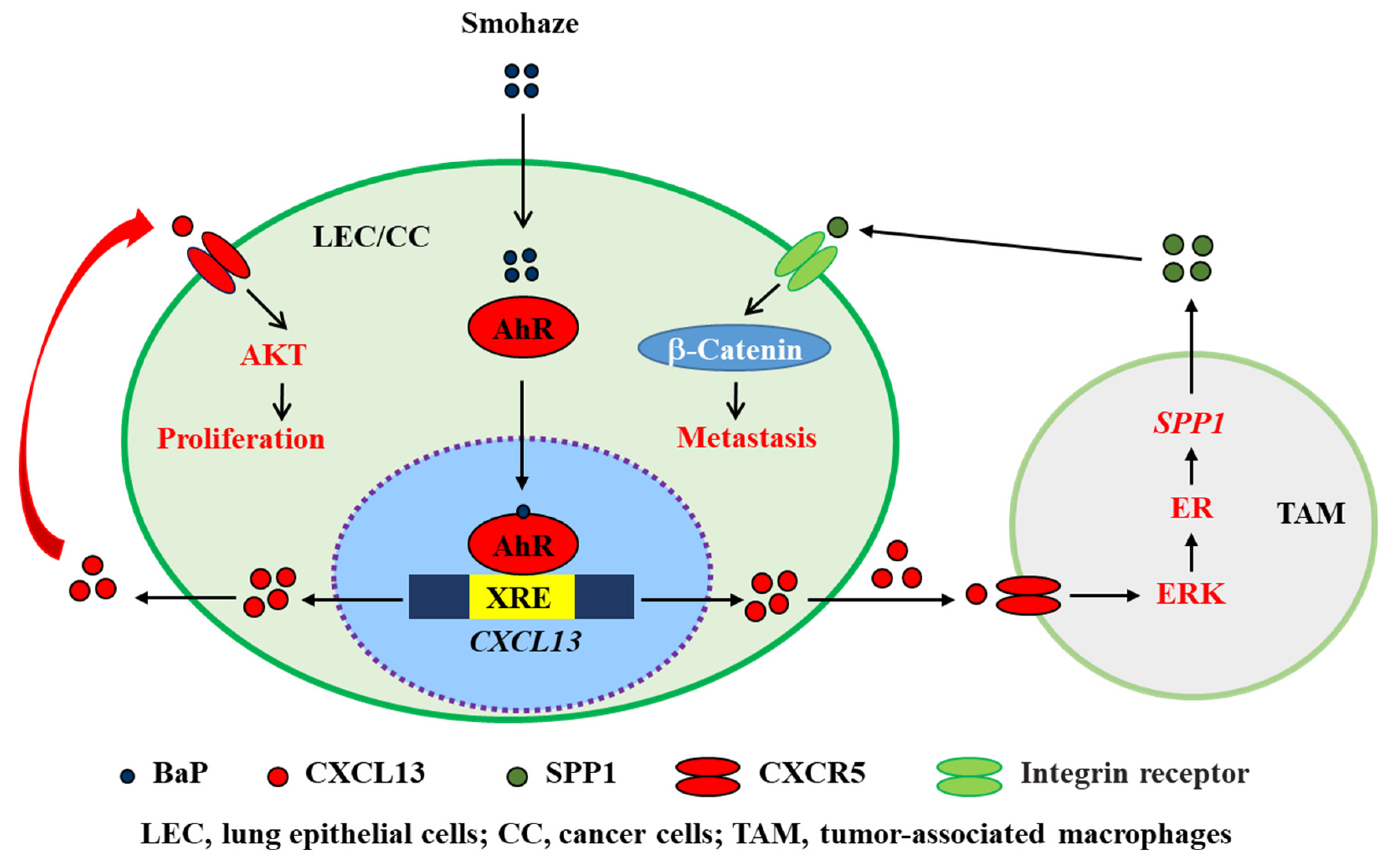

C-X-C chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13) and its receptor, CXCR5, make crucial contributions to this process by triggering intracellular signaling cascades in malignant cells and modulating the sophisticated TME in an autocrine or paracrine fashion. The CXCL13/CXCR5 axis has a dominant role in B cell recruitment and tertiary lymphoid structure formation, which activate immune responses against some tumors. In most cancer types, the CXCL13/CXCR5 axis mediates pro-neoplastic immune reactions by recruiting suppressive immune cells into tumor tissues. Tobacco smoke and haze (smohaze) and the carcinogen benzo(a)pyrene induce the secretion of CXCL13 by lung epithelial cells, which contributes to environmental lung carcinogenesis.

- C-X-C chemokine ligand 13 (CXCL13)

- C-X-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CXCR5)

- cancer

- tumor microenvironment

1. Introduction

2. CXCL13/CXCR5 and Immune Homeostasis

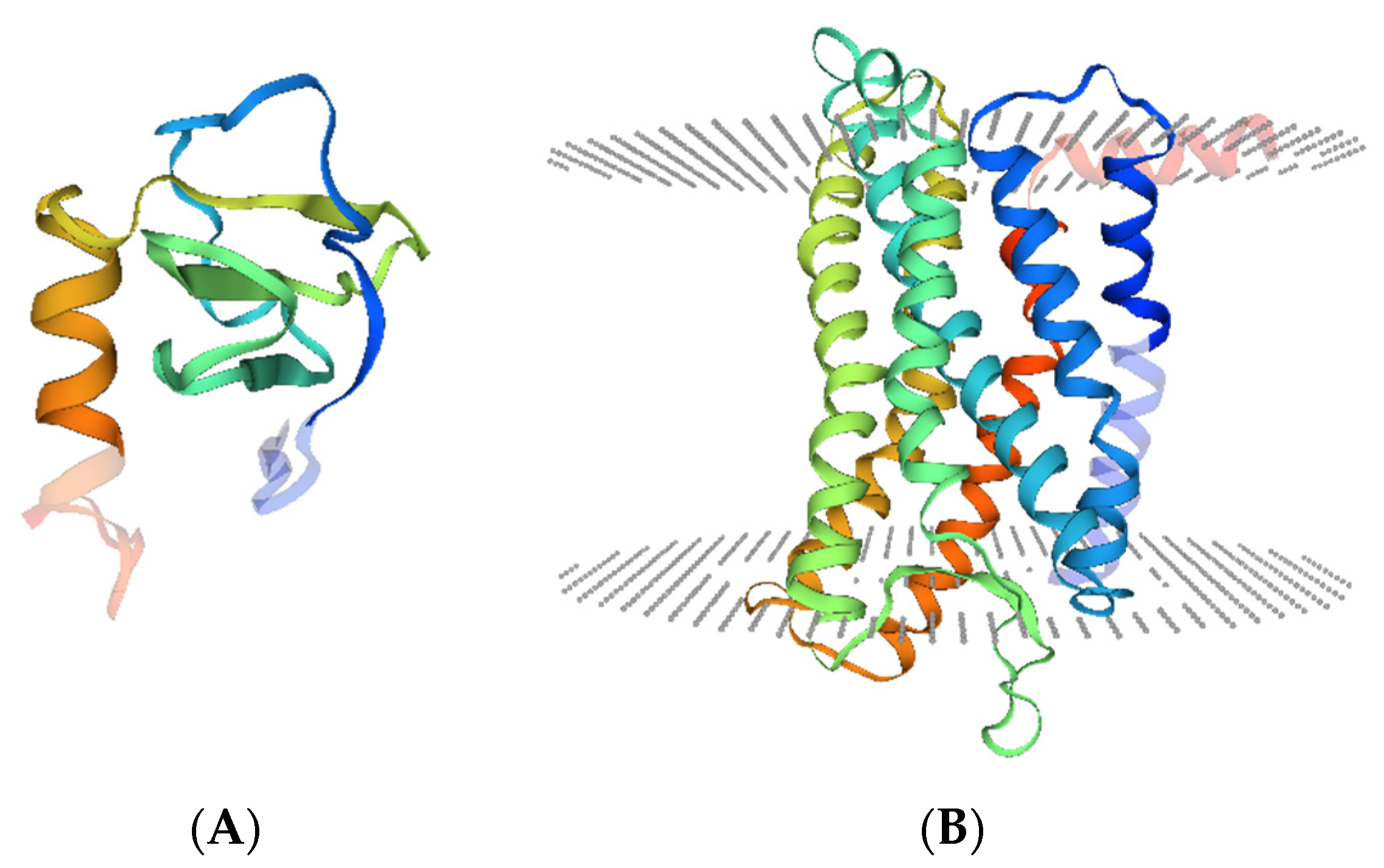

2.1. CXCL13/CXCR5: Genes and Proteins

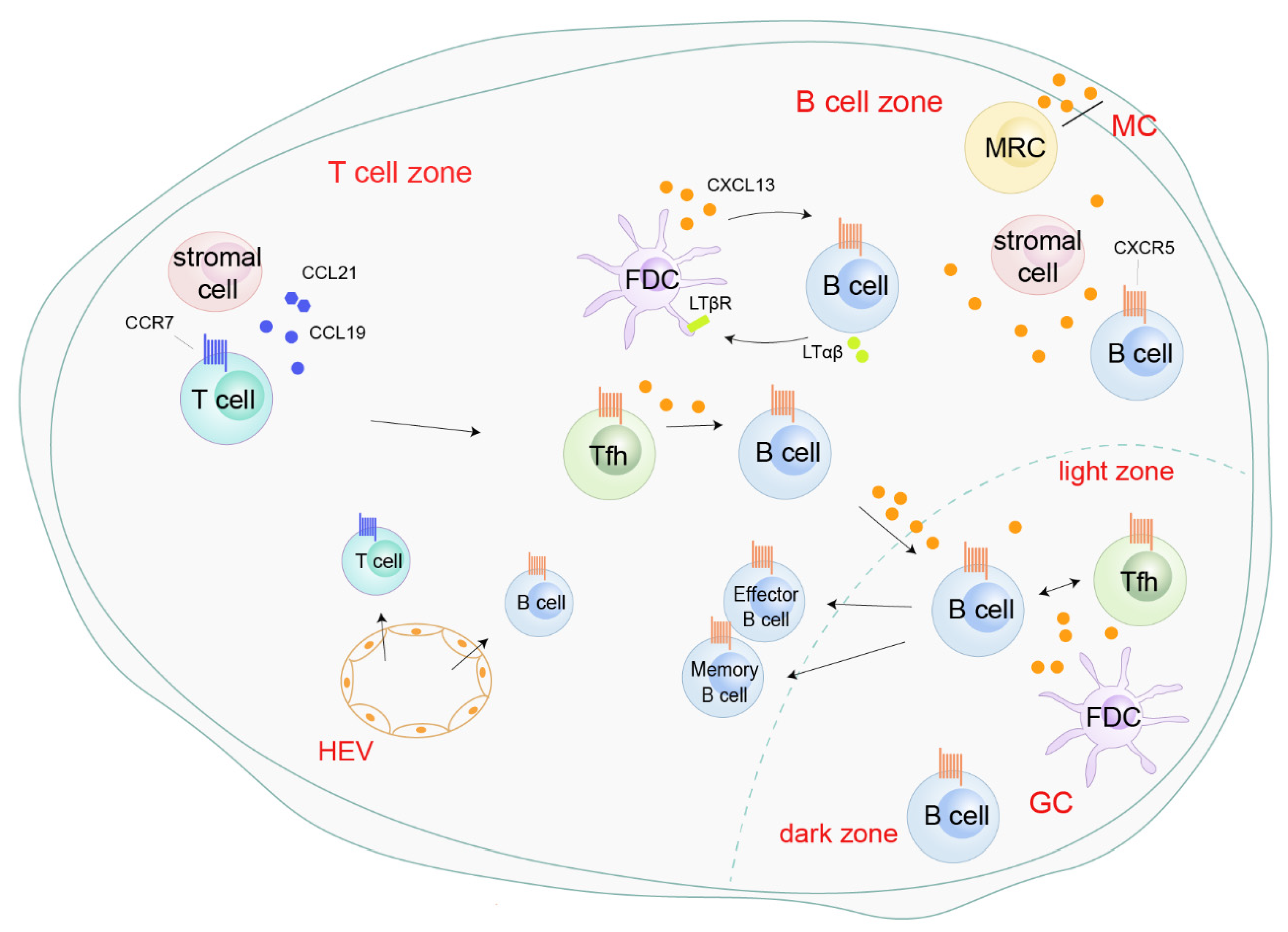

2.2. CXCL13/CXCR5 Axis

2.3. Physiological Functions of CXCL13/CXCR5

3. CXCL13/CXCR5 and Non-Cancerous Diseases

4. CXCL13/CXCR5 and Cancer

4.1. CXCL13 Sources within the Tumor and the Tumor Microenvironment

4.1.1. CXCL13: Cellular Sources within TME

4.1.2. CXCL13: Production under Carcinogen Stimulation

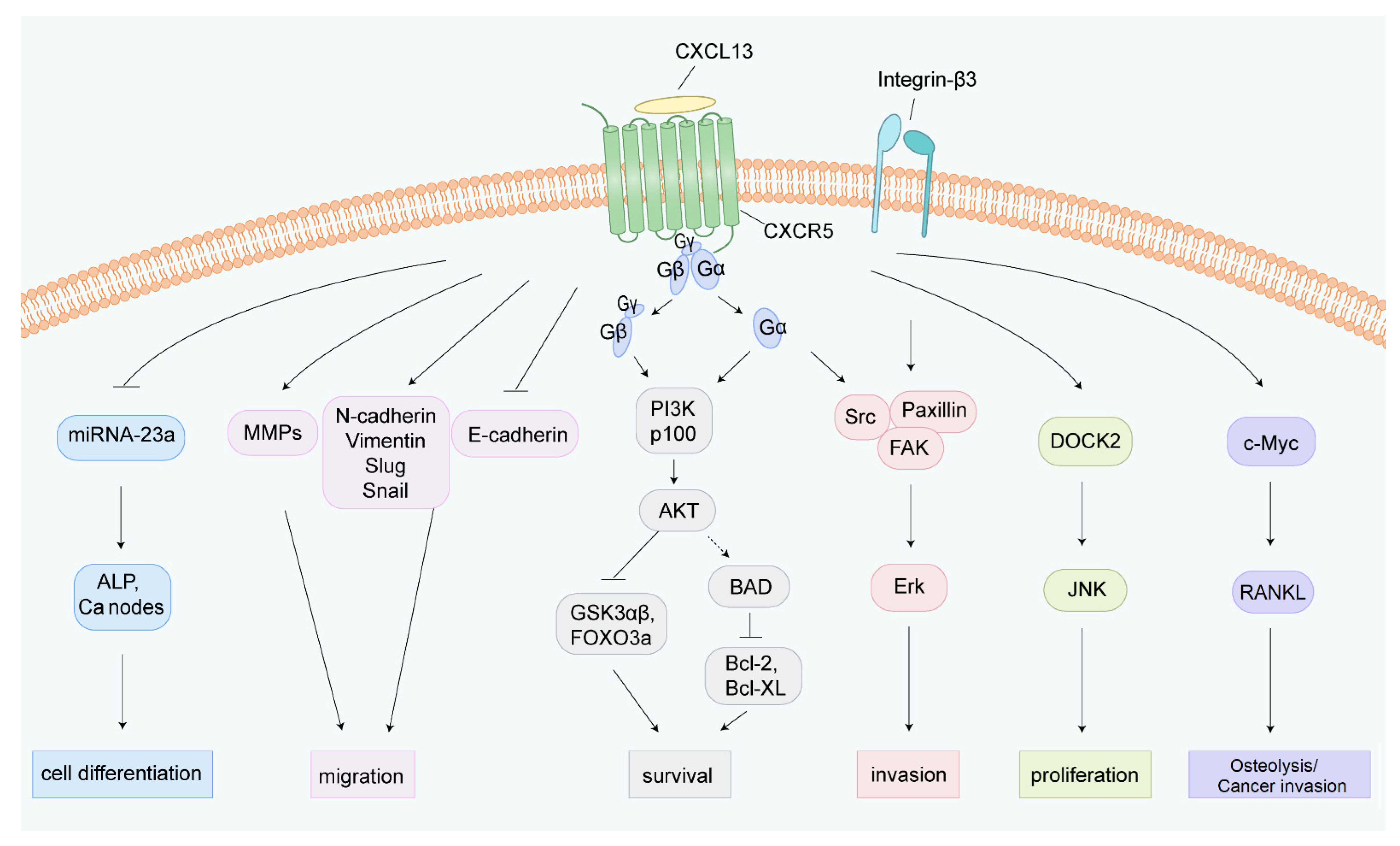

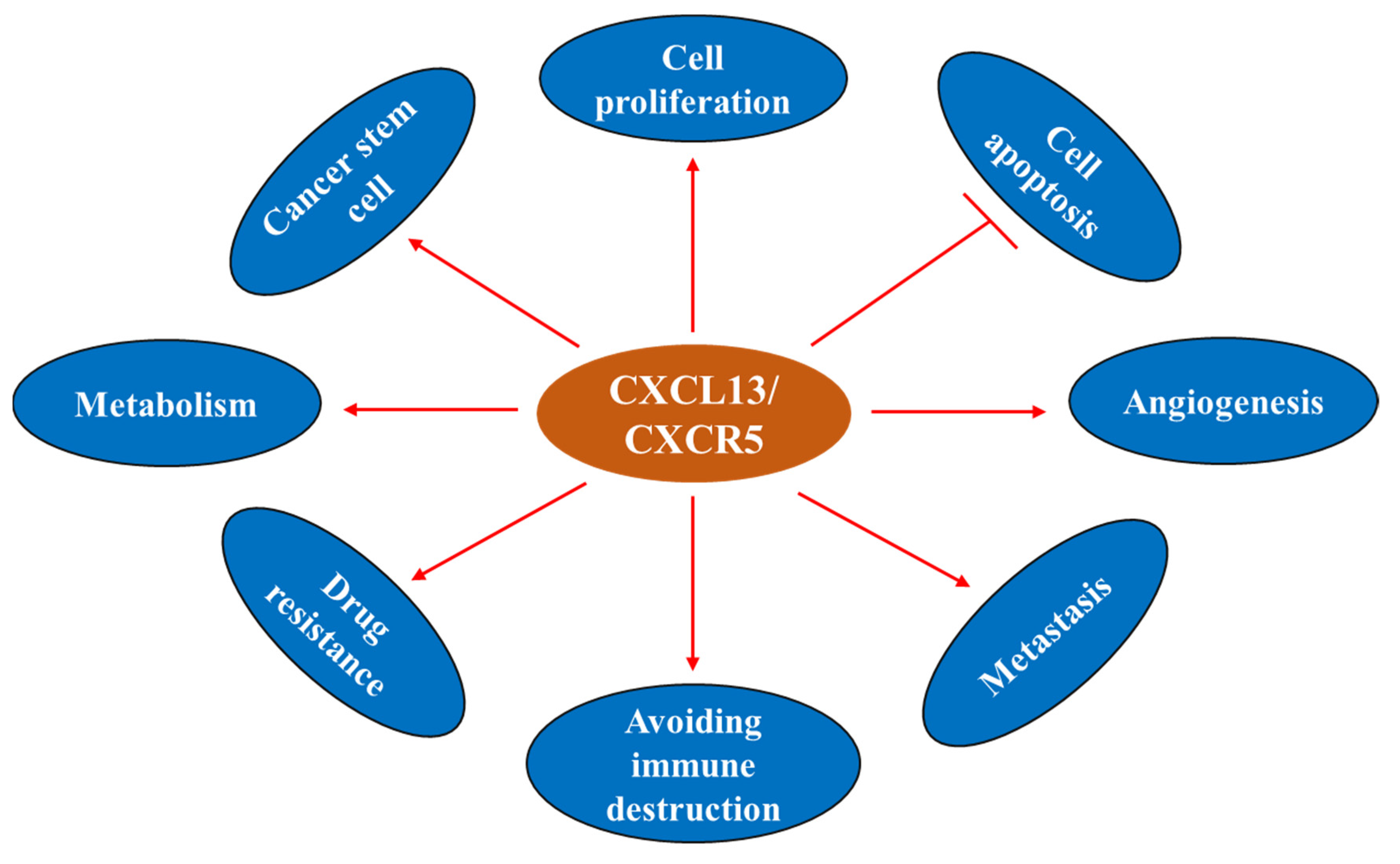

4.2. CXCL13/CXCR5 and Cancer Hallmarks

4.2.1. CXCL13 and Cell Proliferation

4.2.2. CXCL13 and Cell Apoptosis

4.2.3. CXCL13 and Cancer Stem Cell (CSC)

4.2.4. CXCL13 and Drug Resistance

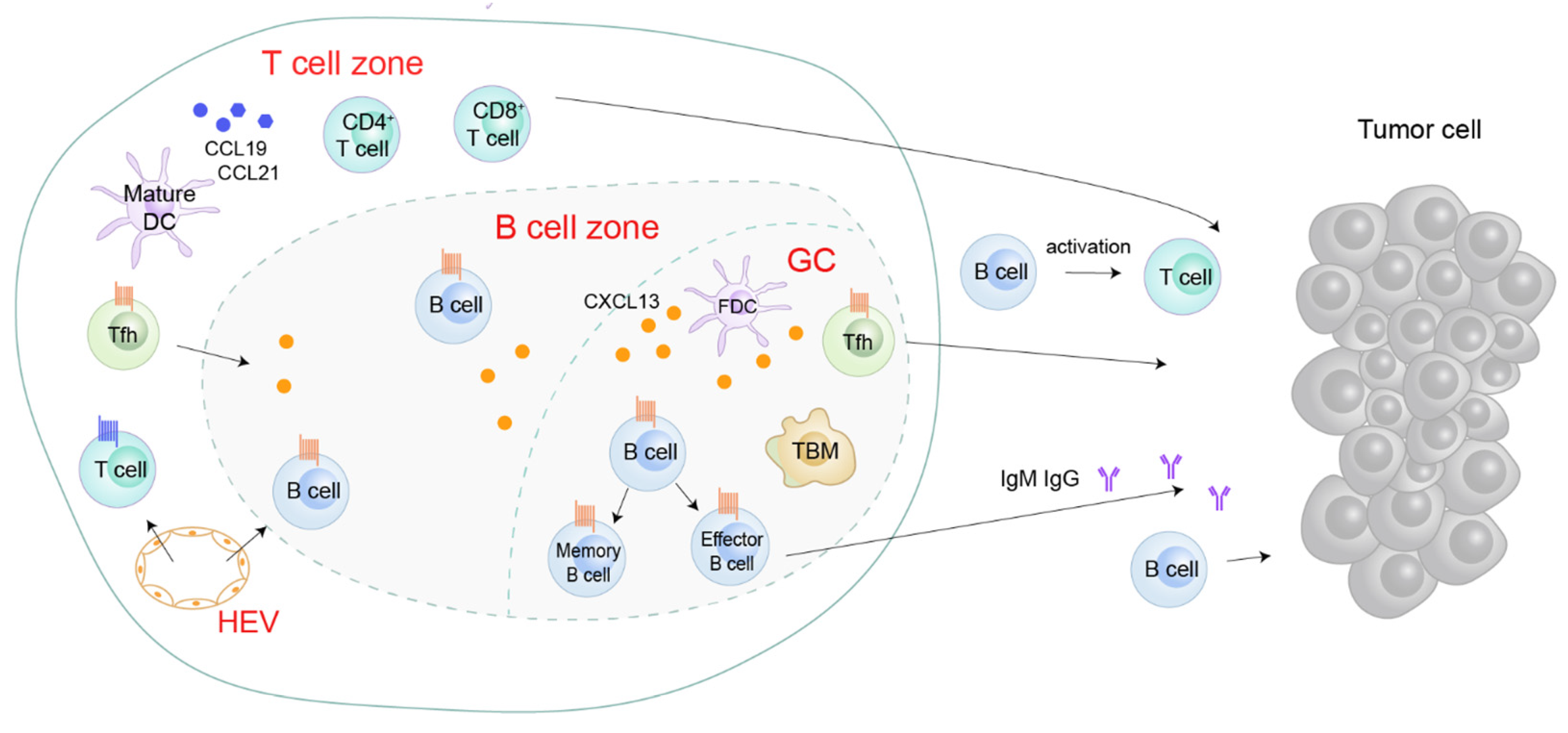

4.2.5. CXCL13/CXCR5 in the Tumor Microenvironment

4.2.6. CXCL13 and Angiogenesis

4.2.7. CXCL13 and Immunometabolic Responses

4.2.8. CXCL13 and Cancer Metastasis

4.3. Regulation of CXCL13 in Tumors

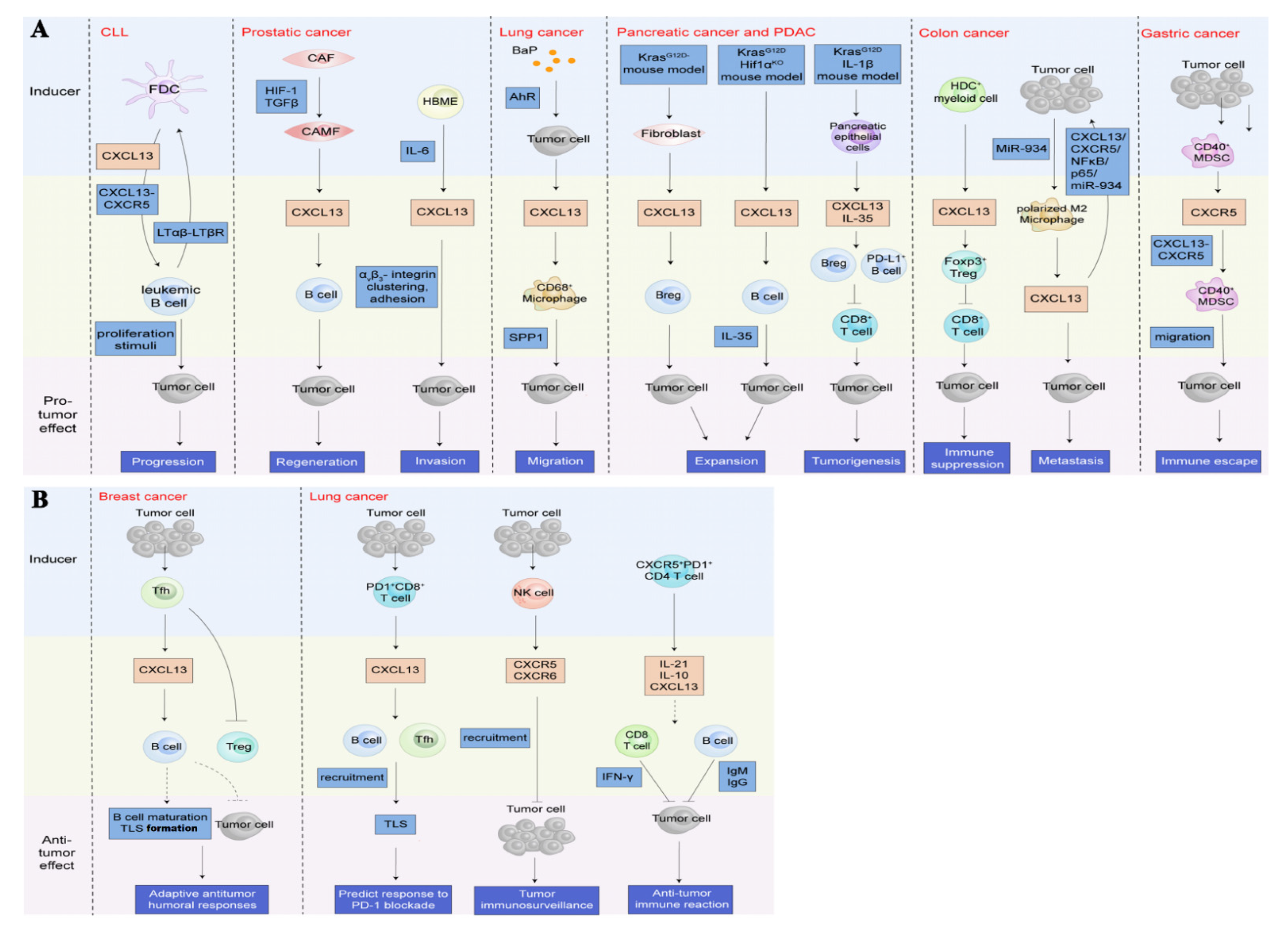

5. CXCL13/CXCR5 in Several Cancer Types

|

Target |

Cancer Type |

Function |

Approach |

In Vivo or In Vitro |

Outcome |

Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CXCL13 |

Prostate cancer |

Induction of prostate cancer cell proliferation and migration |

siRNA and shRNA; antibody |

In vivo; in vitro |

Inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis |

[116] |

|

CXCL13 |

Prostate cancer |

Chemotaxis B cells into regressing tumor |

Antibody |

In vivo |

Preventing B-cell recruitment into tumor under castration |

[104] |

|

CXCL13 |

Breast cancer |

Activating CXCR5/ERK pathway |

Polyclonal antibody |

In vivo; in vitro |

Attenuating tumor volume and growth; inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and promoting its apoptosis |

|

|

CXCL13 |

Breast cancer |

Enhancing the production of RANKL on tumor cells and the interaction between ILC3 and stromal cells |

Antibody |

In vivo |

Attenuating lymph node metastasis |

[118] |

|

CXCL13 |

Lung cancer |

Promotion of cell proliferation; inducing the production of SPP1 by microphage |

Cxcl13−/− mice |

In vivo |

Decreasing the volume of BaP-induced tumor |

[14] |

|

CXCL13 |

PDAC |

Homing B cell into tumor lesions |

Antibody |

Mice harbored KrasG12D PDEC |

Reducing the growth of orthotopic tumor |

[105] |

|

CXCL13 |

Colon cancer |

Induction 5-Fu resistance and association with a worse outcome |

siRNA |

In vitro |

Reducing 5-Fu resistance |

[101] |

|

CXCR5 |

CLL |

CXCR5+ leukemia B cells recruited by CXCL13 to encounter proliferation stimuli |

Cxcr5−/− Eμ-Tcl1 mice |

In vivo |

Attenuating tumor cell proliferation |

[76] |

|

CXCR5 |

Prostate cancer |

Induction of prostate cancer cells proliferation and migration |

siRNA and shRNA |

In vivo; in vitro |

Inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis |

[116] |

|

CXCR5 |

Lung cancer |

CXCR5+ CD68+ macrophages producing SPP1 to promote EMT process |

Cxcr5−/− mice |

In vivo |

Decreasing the volume of BaP-induced tumor |

[14] |

|

CXCR5 |

OSCC |

Induction RANKL expression under CXCL13/CXCR5 axis |

Antibody |

In vitro |

Inhibiting the expression of RANKL |

[64] |

|

TGFβR |

Prostate cancer |

Activating CXCL13-expressing myofibroblasts |

SB-431542 |

In vivo |

Blocking the initiation of castration-resistant prostate cancer |

[77] |

|

NFATc3 |

OSCC |

Nuclear translocation mediated by CXCL13/CXCR5 axis to bind to RANKL promoter region |

siRNA |

In vitro |

Preventing RANKL expression |

[64] |

|

Myofibroblasts |

Prostate cancer |

Induction of CXCL13 expression |

Immunodepletion; phosphodiesterase 5 |

In vivo |

Blocking the initiation of castration-resistant prostate cancer |

[77] |

ILC3, RORγt+ innate lymphoid cell group 3; SPP1, secreted phosphoprotein 1; BaP, benzo(a)pyrene; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PDEC, pancreatic ductal epithelial cells; 5-Fu, 5-Fluorouracil; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; EMT, epithelial to mesenchymal transition; OSCC, oral squamous cell carcinomas; RANKL, RANK ligand; TGFβR, TGFβ receptor; NFATc3, nuclear factor of activated T cells.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/life11121282

References

- Albert Zlotnik, O.Y. Chemokines: A New Classification System and Their Role in Immunity. Immunity 2000, 12, 121–127.

- Murdoch, C.; Finn, A. Chemokine receptors and their role in inflammation and infectious diseases. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2000, 95, 3032–3043.

- Ziarek, J.J.; Kleist, A.B.; London, N.; Raveh, B.; Montpas, N.; Bonneterre, J.; St-Onge, G.; DiCosmo-Ponticello, C.J.; Koplinski, C.A.; Roy, I.; et al. Structural basis for chemokine recognition by a G protein–coupled receptor and implications for receptor activation. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, 471.

- Nagarsheth, N.; Wicha, M.S.; Zou, W. Chemokines in the cancer microenvironment and their relevance in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 559–572.

- Lacalle, R.A.; Blanco, R.; Carmona-Rodriguez, L.; Martin-Leal, A.; Mira, E.; Manes, S. Chemokine Receptor Signaling and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 331, 181–244.

- Lazennec, G.; Richmond, A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: New insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 133–144.

- Raman, D.; Baugher, P.J.; Thu, Y.M.; Richmond, A. Role of chemokines in tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2007, 256, 137–165.

- Belperio, J.A.; Keane, M.P.; Arenberg, D.A.; Addison, C.L.; Ehlert, J.E.; Burdick, M.D.; Strieter, R.M. CXC chemokines in angiogenesis. J. Leukoc Biol. 2000, 68, 1–8.

- Gunn, M.D.; Ngo, V.N.; Ansel, K.M.; Ekland, E.H.; Cyster, J.G.; Williams, L.T. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt’s lymphoma receptor-1. Nature 1998, 391, 799–803.

- Galamb, O.; Gyõrffy, B.; Sipos, F.; Dinya, E.; Krenács, T.; Berczi, L.; Szõke, D.; Spisák, S.; Solymosi, N.; Németh, A.M.; et al. Helicobacter pylori and antrum erosion-specific gene expression patterns: The discriminative role of CXCL13 and VCAM1 transcripts. Helicobacter 2008, 13, 112–126.

- Shi, W.; Yang, B.; Sun, Q.; Meng, J.; Zhao, X.; Du, S.; Li, X.; Jiao, S. PD-1 regulates CXCR5(+) CD4 T cell-mediated proinflammatory functions in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 82, 106295.

- Cha, Z.; Qian, G.; Zang, Y.; Gu, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Tu, X.; Song, H.; et al. Circulating CXCR5+CD4+ T cells assist in the survival and growth of primary diffuse large B cell lymphoma cells through interleukin 10 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 350, 154–160.

- Pimenta, E.M.; De, S.; Weiss, R.; Feng, D.; Hall, K.; Kilic, S.; Bhanot, G.; Ganesan, S.; Ran, S.; Barnes, B.J. IRF5 is a novel regulator of CXCL13 expression in breast cancer that regulates CXCR5(+) B- and T-cell trafficking to tumor-conditioned media. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2015, 93, 486–499.

- Wang, G.Z.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, B.; Wen, Z.S.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, H.B.; Li, G.F.; Huang, Z.L.; Zhou, Y.C.; Feng, L.; et al. The chemokine CXCL13 in lung cancers associated with environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons pollution. Elife 2015, 4, e09419.

- Renaudin, X.; Guervilly, J.H.; Aoufouchi, S.; Rosselli, F. Proteomic analysis reveals a FANCA-modulated neddylation pathway involved in CXCR5 membrane targeting and cell mobility. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3546–3554.

- El-Haibi, C.P.; Sharma, P.; Singh, R.; Gupta, P.; Taub, D.D.; Singh, S.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. Differential G protein subunit expression by prostate cancer cells and their interaction with CXCR5. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 64.

- MacDonald, R.J.; Yen, A. CXCR5 overexpression in HL-60 cells enhances chemotaxis toward CXCL13 without anticipated interaction partners or enhanced MAPK signaling. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2018, 54, 725–735.

- Barroso, R.; Martinez Munoz, L.; Barrondo, S.; Vega, B.; Holgado, B.L.; Lucas, P.; Baillo, A.; Salles, J.; Rodriguez-Frade, J.M.; Mellado, M. EBI2 regulates CXCL13-mediated responses by heterodimerization with CXCR5. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 4841–4854.

- Bookout, A.L.; Finney, A.E.; Guo, R.; Peppel, K.; Koch, W.J.; Daaka, Y. Targeting Gbetagamma signaling to inhibit prostate tumor formation and growth. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 37569–37573.

- Müller, G.; Lipp, M. Signal Transduction by the Chemokine Receptor CXCR5: Structural Requirements for G Protein Activation Analyzed by Chimeric CXCR1/CXCR5 Molecules. Biol. Chem. 2001, 382, 9.

- Dobner, T.; Wolf, I.; Emrich, T.; Lipp, M. Differentiation-specific expression of a novel G protein-coupled receptor from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992, 22, 2795–2799.

- Ansel, K.M.; Ngo, V.N.; Hyman, P.L.; Luther, S.A.; Forster, R.; Sedgwick, J.D.; Browning, J.L.; Lipp, M.; Cyster, J.G. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature 2000, 406, 309–314.

- Legler, D.F.; Loetscher, M.; Roos, R.S.; Clark-Lewis, I.; Baggiolini, M.; Moser, B. B cell-attracting chemokine 1, a human CXC chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues, selectively attracts B lymphocytes via BLR1/CXCR5. J. Exp. Med. 1998, 187, 655–660.

- Mueller, S.N.; Germain, R.N. Stromal cell contributions to the homeostasis and functionality of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 618–629.

- Kaiser, E.; Forster, R.; Wolf, I.; Ebensperger, C.; Kuehl, W.M.; Lipp, M. The G protein-coupled receptor BLR1 is involved in murine B cell differentiation and is also expressed in neuronal tissues. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993, 23, 2532–2539.

- Breitfeld, D.; Ohl, L.; Kremmer, E.; Ellwart, J.; Sallusto, F.; Lipp, M.; Forster, R. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1545–1552.

- Schaerli, P.; Willimann, K.; Lang, A.B.; Lipp, M.; Loetscher, P.; Moser, B. CXC chemokine receptor 5 expression defines follicular homing T cells with B cell helper function. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1553–1562.

- Leon, B.; Ballesteros-Tato, A.; Browning, J.L.; Dunn, R.; Randall, T.D.; Lund, F.E. Regulation of T(H)2 development by CXCR5+ dendritic cells and lymphotoxin-expressing B cells. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 681–690.

- Saeki, H.; Wu, M.; Olasz, E.; Hwang, S.T. A migratory population of skin-derived dendritic cells expresses CXCR5, responds to B lymphocyte chemoattractant in vitro, and co-localizes to B cell zones in lymph nodes in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000, 30, 2808–2814.

- Forster, R.; Mattis, A.E.; Kremmer, E.; Wolf, E.; Brem, G.; Lipp, M. A Putative Chemokine Receptor, BLR1, Directs B Cell Migration to Defined Lymphoid Organs and Specific Anatomic Compartments of the Spleen. Cell 1996, 87, 1037–1047.

- Muller, G.; Hopken, U.E.; Lipp, M. The impact of CCR7 and CXCR5 on lymphoid organ development and systemic immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2003, 195, 117–135.

- Ise, W.; Fujii, K.; Shiroguchi, K.; Ito, A.; Kometani, K.; Takeda, K.; Kawakami, E.; Yamashita, K.; Suzuki, K.; Okada, T.; et al. T Follicular Helper Cell-Germinal Center B Cell Interaction Strength Regulates Entry into Plasma Cell or Recycling Germinal Center Cell Fate. Immunity 2018, 48, 702–715.e4.

- Gao, X.; Lin, L.; Yu, D. Ex Vivo Culture Assay to Measure Human Follicular Helper T (Tfh) Cell-Mediated Human B Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 111–119.

- Havenar-Daughton, C.; Lindqvist, M.; Heit, A.; Wu, J.E.; Reiss, S.M.; Kendric, K.; Belanger, S.; Kasturi, S.P.; Landais, E.; Akondy, R.S.; et al. CXCL13 is a plasma biomarker of germinal center activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2702–2707.

- Bracke, K.R.; Verhamme, F.M.; Seys, L.J.; Bantsimba-Malanda, C.; Cunoosamy, D.M.; Herbst, R.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G. Role of CXCL13 in cigarette smoke-induced lymphoid follicle formation and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 343–355.

- Bombardieri, M.; Lewis, M.; Pitzalis, C. Ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in rheumatic autoimmune diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 141–154.

- Eddens, T.; Elsegeiny, W.; Garcia-Hernadez, M.L.; Castillo, P.; Trevejo-Nunez, G.; Serody, K.; Campfield, B.T.; Khader, S.A.; Chen, K.; Rangel-Moreno, J.; et al. Pneumocystis-Driven Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Formation Requires Th2 and Th17 Immunity. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 3078–3090.

- Mueller, C.G.; Nayar, S.; Gardner, D.; Barone, F. Cellular and Vascular Components of Tertiary Lymphoid Structures. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1845, 17–30.

- Wang, S.S.; Liu, W.; Ly, D.; Xu, H.; Qu, L.; Zhang, L. Tumor-infiltrating B cells: Their role and application in anti-tumor immunity in lung cancer. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2019, 16, 6–18.

- Yu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Lu, H.; Guan, Z.; Huang, J.; Gong, W.; Shi, M.; Ni, L.; et al. Aberrant Humoral Immune Responses in Neurosyphilis: CXCL13/CXCR5 Play a Pivotal Role for B-Cell Recruitment to the Cerebrospinal Fluid. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 534–544.

- Cabrita, R.; Lauss, M.; Sanna, A.; Donia, M.; Skaarup Larsen, M.; Mitra, S.; Johansson, I.; Phung, B.; Harbst, K.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 2020, 577, 561–565.

- Da, Z.; Li, L.; Zhu, J.; Gu, Z.; You, B.; Shan, Y.; Shi, S. CXCL13 Promotes Proliferation of Mesangial Cells by Combination with CXCR5 in SLE. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 2016, 2063985.

- Meraouna, A.; Cizeron-Clairac, G.; Panse, R.L.; Bismuth, J.; Truffault, F.; Tallaksen, C.; Berrih-Aknin, S. The chemokine CXCL13 is a key molecule in autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Blood 2006, 108, 432–440.

- Silina, K.; Soltermann, A.; Attar, F.M.; Casanova, R.; Uckeley, Z.M.; Thut, H.; Wandres, M.; Isajevs, S.; Cheng, P.; Curioni-Fontecedro, A.; et al. Germinal Centers Determine the Prognostic Relevance of Tertiary Lymphoid Structures and Are Impaired by Corticosteroids in Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 1308–1320.

- Denton, A.E.; Innocentin, S.; Carr, E.J.; Bradford, B.M.; Lafouresse, F.; Mabbott, N.A.; Mörbe, U.; Ludewig, B.; Groom, J.R.; Good-Jacobson, K.L.; et al. Type I interferon induces CXCL13 to support ectopic germinal center formation. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 621–637.

- Bellamri, N.; Viel, R.; Morzadec, C.; Lecureur, V.; Joannes, A.; de Latour, B.; Llamas-Gutierrez, F.; Wollin, L.; Jouneau, S.; Vernhet, L. TNF-α and IL-10 Control CXCL13 Expression in Human Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 2492–2502.

- Yoshitomi, H. CXCL13-producing PD-1(hi)CXCR5(-) helper T cells in chronic inflammation. Immunol. Med. 2020, 43, 156–160.

- Bransfield, R.C. The psychoimmunology of lyme/tick-borne diseases and its association with neuropsychiatric symptoms. Open Neurol. 2012, 6, 88–93.

- Traianos, E.Y.; Locke, J.; Lendrem, D.; Bowman, S.; Hargreaves, B.; Macrae, V.; Tarn, J.R.; Ng, W.-F. Serum CXCL13 levels are associated with lymphoma risk and lymphoma occurrence in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 541–548.

- Colafrancesco, S.; Priori, R.; Smith, C.G.; Minniti, A.; Iannizzotto, V.; Pipi, E.; Lucchesi, D.; Pontarini, E.; Nayar, S.; Campos, J.; et al. CXCL13 as biomarker for histological involvement in Sjogren’s syndrome. Rheumatology 2020, 59, 165–170.

- Shiao, Y.M.; Lee, C.C.; Hsu, Y.H.; Huang, S.F.; Lin, C.Y.; Li, L.H.; Fann, C.S.; Tsai, C.Y.; Tsai, S.F.; Chiu, H.C. Ectopic and high CXCL13 chemokine expression in myasthenia gravis with thymic lymphoid hyperplasia. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 221, 101–106.

- van der Vorst, E.P.C.; Daissormont, I.; Aslani, M.; Seijkens, T.; Wijnands, E.; Lutgens, E.; Duchene, J.; Santovito, D.; Döring, Y.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Interruption of the CXCL13/CXCR5 Chemokine Axis Enhances Plasma IgM Levels and Attenuates Atherosclerosis Development. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 120, 344–347.

- Bao, Y.-Q.; Wang, J.-P.; Dai, Z.-W.; Mao, Y.-M.; Wu, J.; Guo, H.-S.; Xia, Y.-R.; Ye, D.-Q. Increased circulating CXCL13 levels in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 39, 281–290.

- Rupprecht, T.A.; Manz, K.M.; Fingerle, V.; Lechner, C.; Klein, M.; Pfirrmann, M.; Koedel, U. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid CXCL13 for acute Lyme neuroborreliosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 1234–1240.

- Kusuyama, J.; Bandow, K.; Ohnishi, T.; Amir, M.S.; Shima, K.; Semba, I.; Matsuguchi, T. CXCL13 is a differentiation- and hypoxia-induced adipocytokine that exacerbates the inflammatory phenotype of adipocytes through PHLPP1 induction. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 3533–3548.

- Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Xiong, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Yin, L.; Tu, C.; Wang, H.; Xiang, X.; Xu, J.; et al. CXCL13/CXCR5 signaling contributes to diabetes-induced tactile allodynia via activating pERK, pSTAT3, pAKT pathways and pro-inflammatory cytokines production in the spinal cord of male mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019, 80, 711–724.

- Zhang, G.; Ducatelle, R.; De Bruyne, E.; Joosten, M.; Bosschem, I.; Smet, A.; Haesebrouck, F.; Flahou, B. Role of γ-glutamyltranspeptidase in the pathogenesis of Helicobacter suis and Helicobacter pylori infections. Vet. Res. 2015, 46, 31.

- Mazzucchelli, L.; Blaser, A.; Kappeler, A.; Scharli, P.; Laissue, J.A.; Baggiolini, M.; Uguccioni, M. BCA-1 is highly expressed in Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and gastric lymphoma. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 104, R49–R54.

- Yamamoto, K.; Nishiumi, S.; Yang, L.; Klimatcheva, E.; Pandina, T.; Takahashi, S.; Matsui, H.; Nakamura, M.; Zauderer, M.; Yoshida, M.; et al. Anti-CXCL13 antibody can inhibit the formation of gastric lymphoid follicles induced by Helicobacter infection. Mucosal. Immunol. 2014, 7, 1244–1254.

- Sahini, N.; Borlak, J. Genomics of human fatty liver disease reveal mechanistically linked lipid droplet-associated gene regulations in bland steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Transl. Res. 2016, 177, 41–69.

- Jiang, B.C.; Cao, D.L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.J.; He, L.N.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, W.W.; Wu, X.B.; Berta, T.; Ji, R.R.; et al. CXCL13 drives spinal astrocyte activation and neuropathic pain via CXCR5. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 745–761.

- Trolese, M.C.; Mariani, A.; Terao, M.; de Paola, M.; Fabbrizio, P.; Sironi, F.; Kurosaki, M.; Bonanno, S.; Marcuzzo, S.; Bernasconi, P.; et al. CXCL13/CXCR5 signalling is pivotal to preserve motor neurons in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EBioMedicine 2020, 62, 103097.

- El-Haibi, C.P.; Singh, R.; Gupta, P.; Sharma, P.K.; Greenleaf, K.N.; Singh, S.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. Antibody Microarray Analysis of Signaling Networks Regulated by Cxcl13 and Cxcr5 in Prostate Cancer. J. Proteom. Bioinform. 2012, 5, 177–184.

- Yuvaraj, S.; Griffin, A.C.; Sundaram, K.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Norris, J.S.; Reddy, S.V. A novel function of CXCL13 to stimulate RANK ligand expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 2009, 7, 1399–1407.

- Cha, Z.; Gu, H.; Zang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, W.; Qin, A.; Zhu, L.; Tu, X.; Cheng, N.; et al. The prevalence and function of CD4(+)CXCR5(+)Foxp3(+) follicular regulatory T cells in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 61, 132–139.

- Meng, X.; Yu, X.; Dong, Q.; Xu, X.; Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhou, C. Distribution of circulating follicular helper T cells and expression of interleukin-21 and chemokine C-X-C ligand 13 in gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 3917–3922.

- Ohandjo, A.Q.; Liu, Z.; Dammer, E.B.; Dill, C.D.; Griffen, T.L.; Carey, K.M.; Hinton, D.E.; Meller, R.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. Transcriptome Network Analysis Identifies CXCL13-CXCR5 Signaling Modules in the Prostate Tumor Immune Microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14963.

- Hussain, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.Z.; Zhou, G.B. CXCL13 Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1302, 71–90.

- Goswami, S.; Chen, Y.; Anandhan, S.; Szabo, P.M.; Basu, S.; Blando, J.M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Natarajan, S.M.; Xiong, L.; et al. ARID1A mutation plus CXCL13 expression act as combinatorial biomarkers to predict responses to immune checkpoint therapy in mUCC. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, 548.

- Im, S.J.; Hashimoto, M.; Gerner, M.Y.; Lee, J.; Kissick, H.T.; Burger, M.C.; Shan, Q.; Hale, J.S.; Lee, J.; Nasti, T.H.; et al. Defining CD8+ T cells that provide the proliferative burst after PD-1 therapy. Nature 2016, 537, 417–421.

- He, R.; Hou, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, A.; Bai, Q.; Han, M.; Yang, Y.; Wei, G.; Shen, T.; Yang, X.; et al. Follicular CXCR5- expressing CD8(+) T cells curtail chronic viral infection. Nature 2016, 537, 412–428.

- Tian, F.; Ji, X.L.; Xiao, W.A.; Wang, B.; Wang, F. CXCL13 Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells by Inhibiting miR-23a Expression. Stem. Cells Int. 2015, 2015, 632305.

- Biswas, S.; Sengupta, S.; Roy Chowdhury, S.; Jana, S.; Mandal, G.; Mandal, P.K.; Saha, N.; Malhotra, V.; Gupta, A.; Kuprash, D.V.; et al. CXCL13-CXCR5 co-expression regulates epithelial to mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells during lymph node metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 143, 265–276.

- Sambandam, Y.; Sundaram, K.; Liu, A.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Ries, W.L.; Reddy, S.V. CXCL13 activation of c-Myc induces RANK ligand expression in stromal/preosteoblast cells in the oral squamous cell carcinoma tumor-bone microenvironment. Oncogene 2013, 32, 97–105.

- Ohtani, H.; Komeno, T.; Agatsuma, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Noguchi, M.; Nakamura, N. Follicular Dendritic Cell Meshwork in Angioimmunoblastic T-Cell Lymphoma Is Characterized by Accumulation of CXCL13(+) Cells. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 2015, 55, 61–69.

- Heinig, K.; Gatjen, M.; Grau, M.; Stache, V.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Gerlach, K.; Niesner, R.A.; Cseresnyes, Z.; Hauser, A.E.; Lenz, P.; et al. Access to follicular dendritic cells is a pivotal step in murine chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cell activation and proliferation. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 1448–1465.

- Ammirante, M.; Shalapour, S.; Kang, Y.; Jamieson, C.A.; Karin, M. Tissue injury and hypoxia promote malignant progression of prostate cancer by inducing CXCL13 expression in tumor myofibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14776–14781.

- Singh, S.; Singh, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Singh, U.P.; Rai, S.N.; Chung, L.W.K.; Cooper, C.R.; Novakovic, K.R.; Grizzle, W.E.; Lillard, J.W. Serum CXCL13 positively correlates with prostatic disease, prostate-specific antigen and mediates prostate cancer cell invasion, integrin clustering and cell adhesion. Cancer Lett. 2009, 283, 29–35.

- Gu-Trantien, C.; Migliori, E.; Buisseret, L.; de Wind, A.; Brohee, S.; Garaud, S.; Noel, G.; Dang Chi, V.L.; Lodewyckx, J.N.; Naveaux, C.; et al. CXCL13-producing TFH cells link immune suppression and adaptive memory in human breast cancer. JCI Insight 2017, 2, 11.

- Thommen, D.S.; Koelzer, V.H.; Herzig, P.; Roller, A.; Trefny, M.; Dimeloe, S.; Kiialainen, A.; Hanhart, J.; Schill, C.; Hess, C.; et al. A transcriptionally and functionally distinct PD-1(+) CD8(+) T cell pool with predictive potential in non-small-cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 blockade. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 994–1004.

- Workel, H.H.; Lubbers, J.M.; Arnold, R.; Prins, T.M.; van der Vlies, P.; de Lange, K.; Bosse, T.; van Gool, I.C.; Eggink, F.A.; Wouters, M.C.A.; et al. A Transcriptionally Distinct CXCL13(+)CD103(+)CD8(+) T-cell Population Is Associated with B-cell Recruitment and Neoantigen Load in Human Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 784–796.

- Zhou, G. Tobacco, air pollution, environmental carcinogenesis, and thoughts on conquering strategies of lung cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2019, 16, 700.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/ (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Shiels, M.S.; Pfeiffer, R.M.; Hildesheim, A.; Engels, E.A.; Kemp, T.J.; Park, J.-H.; Katki, H.A.; Koshiol, J.; Shelton, G.; Caporaso, N.E.; et al. Inflammation Markers and Prospective Risk for Lung Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1871–1880.

- Zhao, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, G.; Bi, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liao, Y.; Jin, S.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Pan, L.; et al. CXCL13 promotes intestinal tumorigenesis through the activation of epithelial AKT signaling. Cancer Lett. 2021, 511, 1–14.

- Kazanietz, M.G.; Durando, M.; Cooke, M. CXCL13 and Its Receptor CXCR5 in Cancer: Inflammation, Immune Response, and Beyond. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 471.

- Zheng, Z.; Cai, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, D.; Zhong, Q.; Xie, W. CXCL13/CXCR5 Axis Predicts Poor Prognosis and Promotes Progression Through PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 682.

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, H.; Fu, L.; Pan, G.; Sun, Y. CXCL13-CXCR5 axis promotes the growth and invasion of colon cancer cells via PI3K/AKT pathway. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2015, 400, 287–295.

- Meijer, J.; Zeelenberg, I.S.; Sipos, B.; Roos, E. The CXCR5 chemokine receptor is expressed by carcinoma cells and promotes growth of colon carcinoma in the liver. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 9576–9582.

- El Haibi, C.P.; Sharma, P.K.; Singh, R.; Johnson, P.R.; Suttles, J.; Singh, S.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. PI3Kp110-, Src-, FAK-dependent and DOCK2-independent migration and invasion of CXCL13-stimulated prostate cancer cells. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 85.

- El-Haibi, C.P.; Singh, R.; Sharma, P.K.; Singh, S.; Lillard, J.W., Jr. CXCL13 mediates prostate cancer cell proliferation through JNK signalling and invasion through ERK activation. Cell Prolif. 2011, 44, 311–319.

- Ticchioni, M.; Essafi, M.; Jeandel, P.Y.; Davi, F.; Cassuto, J.P.; Deckert, M.; Bernard, A. Homeostatic chemokines increase survival of B-chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells through inactivation of transcription factor FOXO3a. Oncogene 2007, 26, 7081–7091.

- Ma, J.J.; Jiang, L.; Tong, D.Y.; Ren, Y.N.; Sheng, M.F.; Liu, H.C. CXCL13 inhibition induce the apoptosis of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells through blocking CXCR5/ERK signaling pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 8755–8762.

- Hu, C.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.; Yang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Shen, Q.; et al. PEG10 activation by CXCR5 and CCR7 CD19+CD34+ B cells acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2004, 1, 280–294.

- Chunsong, H.; Yuling, H.; Li, W.; Jie, X.; Gang, Z.; Qiuping, Z.; Qingping, G.; Kejian, Z.; Li, Q.; Chang, A.E.; et al. CXC chemokine ligand 13 and CC chemokine ligand 19 cooperatively render resistance to apoptosis in B cell lineage acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia CD23+CD5+ B cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 6713–6722.

- Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, W. Age-related macular degeneration phenotypes are associated with increased tumor necrosis-alpha and subretinal immune cells in aged Cxcr5 knockout mice. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173716.

- Wang, W.J.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.S.; Huang, Y.Q.; Ma, Y.Y.; Qi, J.; Shi, J.P.; Li, W. Assessing the prognostic value of stemness-related genes in breast cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18325.

- Sorrentino, C.; Ciummo, S.L.; Cipollone, G.; Caputo, S.; Bellone, M.; Di Carlo, E. Interleukin-30/IL27p28 Shapes Prostate Cancer Stem-like Cell Behavior and Is Critical for Tumor Onset and Metastasization. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 2654–2668.

- Shalapour, S.; Font-Burgada, J.; Di Caro, G.; Zhong, Z.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; Dhar, D.; Willimsky, G.; Ammirante, M.; Strasner, A.; Hansel, D.E.; et al. Immunosuppressive plasma cells impede T-cell-dependent immunogenic chemotherapy. Nature 2015, 521, 94–98.

- Zhang, G.; Miao, F.; Xu, J.; Wang, R. Mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow regulate invasion and drug resistance of multiple myeloma cells by secreting chemokine CXCL13. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 20, 209.

- Zhang, G.; Luo, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, E.; Xu, J.; Wang, F.; Cao, G.; Ju, Z.; Jin, D.; Huang, X.; et al. CXCL-13 Regulates Resistance to 5-Fluorouracil in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2020, 52, 622–633.

- Fornecker, L.M.; Muller, L.; Bertrand, F.; Paul, N.; Pichot, A.; Herbrecht, R.; Chenard, M.P.; Mauvieux, L.; Vallat, L.; Bahram, S.; et al. Multi-omics dataset to decipher the complexity of drug resistance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 895.

- Medina, D.J.; Goodell, L.; Glod, J.; Gélinas, C.; Rabson, A.B.; Strair, R.K. Mesenchymal stromal cells protect mantle cell lymphoma cells from spontaneous and drug-induced apoptosis through secretion of B-cell activating factor and activation of the canonical and non-canonical nuclear factor κB pathways. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1255.

- Ammirante, M.; Luo, J.L.; Grivennikov, S.; Nedospasov, S.; Karin, M. B-cell-derived lymphotoxin promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature 2010, 464, 302–305.

- Pylayeva-Gupta, Y.; Das, S.; Handler, J.S.; Hajdu, C.H.; Coffre, M.; Koralov, S.B.; Bar-Sagi, D. IL35-Producing B Cells Promote the Development of Pancreatic Neoplasia. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 247–255.

- Takahashi, R.; Macchini, M.; Sunagawa, M.; Jiang, Z.; Tanaka, T.; Valenti, G.; Renz, B.W.; White, R.A.; Hayakawa, Y.; Westphalen, C.B.; et al. Interleukin-1beta-induced pancreatitis promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via B lymphocyte-mediated immune suppression. Gut 2020, 70, 330–341.

- Lee, K.E.; Spata, M.; Bayne, L.J.; Buza, E.L.; Durham, A.C.; Allman, D.; Vonderheide, R.H.; Simon, M.C. Hif1a Deletion Reveals Pro-Neoplastic Function of B Cells in Pancreatic Neoplasia. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 256–269.

- Chen, X.; Takemoto, Y.; Deng, H.; Middelhoff, M.; Friedman, R.A.; Chu, T.H.; Churchill, M.J.; Ma, Y.; Nagar, K.K.; Tailor, Y.H.; et al. Histidine decarboxylase (HDC)-expressing granulocytic myeloid cells induce and recruit Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in murine colon cancer. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1290034.

- Ding, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, W. CD40 controls CXCR5-induced recruitment of myeloid-derived suppressor cells to gastric cancer. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 38901–38911.

- Gillard-Bocquet, M.; Caer, C.; Cagnard, N.; Crozet, L.; Perez, M.; Fridman, W.H.; Sautes-Fridman, C.; Cremer, I. Lung tumor microenvironment induces specific gene expression signature in intratumoral NK cells. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 19.

- Keeley, E.C.; Mehrad, B.; Strieter, R.M. CXC chemokines in cancer angiogenesis and metastases. Adv. Cancer Res. 2010, 106, 91–111.

- Spinetti, G.; Camarda, G.; Bernardini, G.; Romano Di Peppe, S.; Capogrossi, M.C.; Napolitano, M. The Chemokine CXCL13 (BCA-1) Inhibits FGF-2 Effects on Endothelial Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 289, 19–24.

- Tsai, C.H.; Chen, C.J.; Gong, C.L.; Liu, S.C.; Chen, P.C.; Huang, C.C.; Hu, S.L.; Wang, S.W.; Tang, C.H. CXCL13/CXCR5 axis facilitates endothelial progenitor cell homing and angiogenesis during rheumatoid arthritis progression. Cell Death Disease 2021, 12, 846.

- Nagai, M.; Noguchi, R.; Takahashi, D.; Morikawa, T.; Koshida, K.; Komiyama, S.; Ishihara, N.; Yamada, T.; Kawamura, Y.I.; Muroi, K.; et al. Fasting-Refeeding Impacts Immune Cell Dynamics and Mucosal Immune Responses. Cell 2019, 178, 1072–1087.e14.

- Jordan, S.; Tung, N.; Casanova-Acebes, M.; Chang, C.; Cantoni, C.; Zhang, D.; Wirtz, T.H.; Naik, S.; Rose, S.A.; Brocker, C.N.; et al. Dietary Intake Regulates the Circulating Inflammatory Monocyte Pool. Cell 2019, 178, 1102–1114.

- Garg, R.; Blando, J.M.; Perez, C.J.; Abba, M.C.; Benavides, F.; Kazanietz, M.G. Protein Kinase C Epsilon Cooperates with PTEN Loss for Prostate Tumorigenesis through the CXCL13-CXCR5 Pathway. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 375–388.

- Zhang, L.; Teng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Qu, J.; Hou, K.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Qu, X. C-Src-mediated RANKL-induced breast cancer cell migration by activation of the ERK and Akt pathway. Oncol Lett. 2012, 3, 395–400.

- Irshad, S.; Flores-Borja, F.; Lawler, K.; Monypenny, J.; Evans, R.; Male, V.; Gordon, P.; Cheung, A.; Gazinska, P.; Noor, F.; et al. RORgammat(+) Innate Lymphoid Cells Promote Lymph Node Metastasis of Breast Cancers. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1083–1096.

- Yan, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Yankui, L.; Jingjie, F.; Linfang, J.; Yong, P.; Dong, H.; Xiaowei, Q. The Expression and Significance of CXCR5 and MMP-13 in Colorectal Cancer. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 73, 253–259.

- Baeuerle, P.A.; Henkel, T. Function and activation of NF-kappa B in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 141–179.

- Biswas, S.; Roy Chowdhury, S.; Mandal, G.; Purohit, S.; Gupta, A.; Bhattacharyya, A. RelA driven co-expression of CXCL13 and CXCR5 is governed by a multifaceted transcriptional program regulating breast cancer progression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis. Dis. 2019, 1865, 502–511.

- Mitkin, N.A.; Hook, C.D.; Schwartz, A.M.; Biswas, S.; Kochetkov, D.V.; Muratova, A.M.; Afanasyeva, M.A.; Kravchenko, J.E.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Kuprash, D.V. p53-dependent expression of CXCR5 chemokine receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9330.

- Geil, W.M.; Yen, A. Nuclear Raf-1 kinase regulates the CXCR5 promoter by associating with NFATc3 to drive retinoic acid-induced leukemic cell differentiation. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 1170–1180.

- Benard, J.; Douc-Rasy, S.; Ahomadegbe, J.C. TP53 family members and human cancers. Hum. Mutat. 2003, 21, 182–191.

- Mitkin, N.A.; Muratova, A.M.; Sharonov, G.V.; Korneev, K.V.; Sviriaeva, E.N.; Mazurov, D.; Schwartz, A.M.; Kuprash, D.V. p63 and p73 repress CXCR5 chemokine receptor gene expression in p53-deficient MCF-7 breast cancer cells during genotoxic stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2017, 1860, 1169–1178.

- Petitprez, F.; de Reynies, A.; Keung, E.Z.; Chen, T.W.; Sun, C.M.; Calderaro, J.; Jeng, Y.M.; Hsiao, L.P.; Lacroix, L.; Bougouin, A.; et al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature 2020, 577, 556–560.

- Xu, L.; Liang, Z.; Li, S.; Ma, J. Signaling via the CXCR5/ERK pathway is mediated by CXCL13 in mice with breast cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 9293–9298.