Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Plant-based meat alternatives (PBMA) are highly processed products that aim to imitate the experience of eating meat by mimicking animal meat in its sensory characteristics such as taste, texture, or aesthetic appearance.

- plant-based diet

- plant-based meat alternatives

- motivational barriers

1. Introduction

In order to arrive at a sustainable future, it is important to rethink existing consumption practices. Meat consumption is in particular challenging in this regard as it places a heavy burden on the environment [4,5,6]. Animal-based foods have a bigger ecological footprint than plant-based foods, emitting more greenhouse gas emissions, requiring more land and nitrogen, and impacting terrestrial and aquatic biodiversity [7]. Consequently, increasing the consumption of plant-based foods, e.g., by replacing meat with meat substitutes, is normatively desirable [8] as it can be considered a ‘win–win’ situation with respect to both health and environmental protection [7].

Plant-based meat alternatives (PBMA) are highly processed products which try to mimic the ‘meaty’ characteristics of animal meat products, for example the ‘bleeding’ of a burger patty [9]. According to Slade [10] (p. 428), “there is a culinary race to create a plant-based burger that is indistinguishable from beef”. The highly successful Beyond Burger even advertises with a “Now even meatier” claim [11]. In addition to plant-based burger patties, there are also PBMA that mimic mince, sausages, or chicken with their typical taste, texture, and physical appearance. PBMA are intended to replace the meat component in many dishes due to their similarities in form, taste, and preparation method. However, that also means that those meat substitutes are oftentimes directly compared to their ‘original’ counterpart meat [12].

While the market for meat substitutes is booming, a majority of consumers are often still not attracted to these products [13]. Even in Switzerland, one of the most progressive countries in the world, average meat consumption per capita (47.8 kg in 2019) is above the global average and willingness to eschew meat among Swiss consumers is low [14].

Accordingly, while more than half of the Swiss population have already tried plant-based products [15], the question arises: what keeps consumers from changing their diet for good.

2. Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: What We Know

2.1. Why People Decide to Ban Meat from Their Diets

There are oftentimes multiple reasons why consumers decide to (at least gradually) remove meat from their diet [12], ranging from animal protection, protection of environmental resources, or personal health and weight control [12,16,21,22,23]. One of the most prominent reasons to renounce meat intake and to adopt a plant-based diet is motivated by health concerns [16,22,24,25,26,27,28]. Medical research indicates that high levels of (especially red and processed) meat consumption can be linked with several diseases, including cancer [29,30] and cardiovascular diseases [31,32,33]. Likewise, especially in high and middle-income countries, the intake of red meat is showing a negative impact on life expectancy [34]. Against this background, Izmirli and Philips [35] found that a large majority of vegetarians stated health reasons as one of the main motivators to refrain from eating meat. This finding is corroborated by self-reports indicating that vegetarians engage more with health issues [36,37,38,39] and are more weight-conscious [38,39,40].

While health concerns might be the reason to adopt a new diet, a recent study found that animal welfare is the main motivation to continue the diet [22]. In particular, vegetarian and/or vegan consumers link the consumption of meat to animal cruelty [35,41,42,43].

Besides ethical reasons (i.e., animal welfare) the role of environmental concerns in the context of meat consumption is growing. While sustainability and environmental concerns in general have been around for many years, its impact on consumer decision-making in the context of meat consumption is yet to unfold. One reason lies in the lack of awareness of the negative impact associated with meat production and consumption [25,44,45,46]. Only in recent years has meat consumption become a moralized issue for a growing number of consumers [47]. There is now a general consensus that meat production is associated with heightened greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity loss [5]. In fact, livestock farming is responsible for 14.5% of greenhouse gas emissions [48]—nearly a third of agriculture’s water footprint [6]—and is a major driver of deforestation [49]. From a consumption perspective, high meat-eaters cause almost twice as many carbon dioxide emissions than vegetarians [50].

2.2. Plant-Based Meat Alternatives (PBMA)

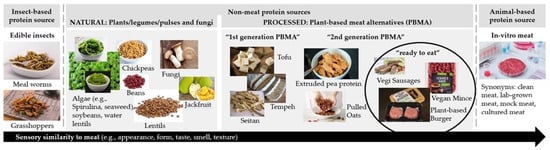

The alternative protein market is growing rapidly [51]. Besides alternative animal-based protein sources such as edible insects or lab-grown meat (i.e., meat produced in the lab without raising and slaughtering the animal, also termed clean meat, cultured meat, in vitro meat, or artificial meat), non-meat protein sources are a promising alternative to traditional meat. The market for non-meat proteins is booming and there is a variety of different products available in the market (see Figure 1). Non-meat protein sources vary in the extent to which they are processed. Foods are considered ‘natural’ if they are free from human intervention, such as removing negatives or adding positives [52,53], and examples of natural non-meat proteins are algae, lentils, pulses, soybeans, or fungi. These proteins are also typical ingredients in vegetarian and vegan cuisine.

Figure 1. Overview of alternative protein sources.

Foods are considered ‘processed’ if they have gone through different production steps or if other ingredients have been added to create the final product. Due to their comparable texture to processed meat products, these products are often perceived and consumed as plant-based meat alternatives (PBMA, also referred to as meat substitutes or meat analogues). Some of them, for example, tofu and tempeh, have been consumed in Asia for centuries [54]. This ‘first generation’ of PBMA were mainly based on soy. While Asian consumers perceive soy as a traditional food in their diet, Western consumers often have a negative image of soy [55]. Moreover, consumers in many countries hold unjustified concerns about genetically modified foods, and soy is often among those foods of concern [56]. ‘Second generation’ PBMA use different ingredients, are more highly processed, and thus manage to improve the sensory experience. New technologies such as extrusion has facilitated the development of food products from extracted pea or oat protein, which create a meat-like structure [19,20]. As part of this second generation PBMA, ‘ready to eat’ PBMA have recently been entering a market that tries to imitate the meaty original and tends to be rather highly processed.

PBMA have the best chance of successfully replacing meat when they closely resemble highly processed meat products in taste and texture and are offered at competitive prices [18].

2.3. Barriers to PBMA Consumption

2.3.1. Structural Adoption Barriers

Several authors have examined barriers that hinder consumers from limiting or banning meat and switching to a plant-based diet (for recent reviews, see [8,14,16,17,18,19,20]). Some of these barriers are predominantly structural and are tied to the general demand of PBMA. For example, it may not always be convenient to purchase PBMA as they have limited availability in grocery stores or restaurants [22]. Another structural barrier is the relative newness of PBMA and a corresponding lack of exposure [12].

In summary, over time and with increasing consumer demand, the structural barriers will likely diminish and may even disappear entirely. According to self-reports, consumers would eat more plant-based foods if these structural barriers disappeared [22].

2.3.2. Motivational Adoption Barriers

Besides structural barriers, motivational barriers exist that will likely persist regardless of improvements in availability, exposure, and affordability. These motivational barriers are summarized as follows: (1) food neophobia, (2) social norms and rituals, and (3) conflicting eating goals. Table 1 lists these barriers as well as exemplary research findings. The motivational barriers jointly contribute to prevailing meat attachment, a positive emotional bond people have with meat [66]. Overcoming meat attachment is a key challenge for increasing PBMA adoption.

Table 1. Motivational Barriers to PBMA Adoption.

| Motivational Barrier | Research Findings |

|---|---|

| Food neophobia |

|

| Social norms and rituals |

|

| Conflicting eating goals | Indulgence:

|

3. Solutions to Increase Consumption of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives

3.1. Solutions to Counter Food Neophobia

It may be difficult to promote plant-based diets among consumers with high food neophobia, as neophobia is very difficult to transform [12]. Yet, one way to reduce neophobia is to make novel foods resemble familiar foods [119], which is the central idea behind PBMA. Against this background, the “Now even meatier” claim on the Beyond Burger can be seen as a good tactic to spark interest in PBMA. Product improvement is therefore seen as the most promising path to counter food neophobia, while providing information on environmental benefits is not likely to be effective in this regard [12].

Beyond product improvement, marketers could try to spark curiosity or turn supposed disadvantages into strength. Labels can be used to highlight aspects of PBMA that grab consumers’ attention and make them reconsider their typical choices. For example, recent consumer research has shown that unattractive produce can be sold more effectively, if it contained “ugly” labels [120]. Notably, this is a different labeling strategy than the more common claims that focus on scientifically verifiable characteristics (e.g., “low fat” or “high vitamins”) or the food’s natural preservation (e.g., “no additives” or “unprocessed”) [52]. This difference is important as sustainability labeling faces the problem that even certified claims are not always trusted [121]. Such skepticism is partly due to consumers using different sources and types of knowledge to decode sustainability claims, in addition to the sheer number of different claims [121]. A label that aligns with the visual assessment of the food (such as “ugly” labels) has a clear advantage in this regard. Using creative labels could therefore be a way to increase consumers’ willingness to try PBMA.

3.2. Solutions to Counter Social Norms and Rituals

Social norms are difficult to ignore, which effectively leaves two solutions to counter their inhibiting influence on a ‘meat-free’ diet. The first option would be to change these norms, but this is admittedly a process that takes time. However, younger generations are much more willing to eat plant-based and try novel foods [122,123]. In a recent study, younger age was associated with increased willingness to try in vitro meat [124], which points to a slow shift in norms over time. In these situations, it is advisable to communicate what is called a trending norm and not the prevalent norm [125]. Instead of highlighting the current state of a behavior (i.e., X% of a reference group show the ‘static norm’), trending norms emphasize the increasingly changing norm over time to elicit (pre-) conformity to this change. Compared to static norms, the dynamic norm information that increasingly more people are beginning to engage in sustainable behavior can effectively foster sustainable behavior that is not yet the norm [126].

3.3. Solutions to Minimize the Influence of Conflicting Eating Goals

Supposedly, the biggest challenge to PBMA adoption is minimizing the inhibiting influence of conflicting eating goals. While continuation in the path towards increased mimicking of traditional meat could be useful in some areas, it may have detrimental effects in others. For example, we have mentioned that PBMA products that closely resemble traditional meat can help overcome food neophobia, and it may also boost perceptions that PBMA can actually be as indulgent as meat. This strategy, however, can backfire with regard to the goal of consuming food that is natural. The more closely PBMA resemble meat dishes, the more obvious the highly processed state will become. Another strategic option is to emphasize both health and environmental benefits in all marketing communication.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su132313271

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!