Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Forestry

Farmland tree cultivation is considered an important option for enhancing wood production. In South India, the native leaf-deciduous tree species Melia dubia is popular for short-rotation plantations. Exploration of key controls of biomass accumulation in tree is very much essential to guide farmers and update agricultural landscape carbon budget. Further, resource conservation and allocation for components of agroforestry. M. dubia growths depends on water availability and how water it requires for its aggressive carbon consumption strategy has yet to be explored.

- aboveground biomass

- climatological water deficit

- farm forestry

- farmland woodlots

1. Introduction

Increasing landscape tree cover and carbon sequestration is considered a cost-effective climate change mitigation tool. While natural secondary succession of native forest tree species is likely the preferred option from an ecological point of view, agroforests, farm woodlots and tree plantations are land-use options that can balance ecological and socio-economic needs [1,2,3,4]. They are considered particularly important regarding the extent and further expansion of global drylands [5,6,7]. Fast-growing short-rotation plantations constitute one potentially important component of future climate-smart ‘designer landscapes’ (see, e.g., [8]), particularly in tropical regions with climatically favorable conditions for fast growth. They can shift pressure from remaining forests and help to meet the booming wood demand in fast-emerging economies [9].

A prime example is India, which houses nearly 18% of the global human population on 2.4% of the world’s land area [10]. Its economic growth and increasing population are associated with an increasing demand for wood and wood-based products [11,12]. In 2019, India imported 8.7 billion USD worth of wood products (Figure S1) [13]. The further projected high economic growth rate [14], continued population growth [12] and forest policy reforms are expected to create substantial additional demand for wood-based products in the coming years [15]. An additional, intrinsic value of landscape tree cover may further arise from future ecosystem service payment schemes for carbon storage or other protective purposes.

Tree plantations in India and elsewhere in the tropics are often established from a very limited number of ‘classic’, highly productive plantation species [16,17,18,19]. Within relatively short rotation cycles, which vary among species but are often around ten years, substantial aboveground biomass (AGB) is accumulated. For example, an AGB of about 140 Mg ha−1 was reported for nine-year-old Eucalyptus tereticornis plantations in India [20]. There are, however, controversies about potential negative impacts of some introduced plantation species on soil, water and biodiversity [21,22,23]. This has led to a ban of Eucalyptus and Acacia plantations in some southern states of India [24].

Among the tree species commonly used for plantation establishment in India, the native Melia dubia Cav. (Meliaceae) is gaining popularity due to its fast growth, straight boles and self-pruning, and its ability to cope with different edaphic and climate conditions [25,26]. It occurs naturally in the moist tropical forests of peninsular and northeastern India and can also be found, either naturally or introduced, in Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Australia and Ghana [27,28]. M. dubia is a light-demanding, deciduous tree species [29,30] and its wood is suitable for plywood, paper and engineered-wood industries [27,31,32]. However, studies on AGB and the growth of M. dubia are rare so far, and with exception of one study on the effects of varying stand densities [33], its growth potential has not yet been assessed comprehensively across gradients in water and nutrient availability.

For tropical trees, several studies reported that biomass and growth are often largely controlled by climate and specifically by water availability, while factors such as soil or disturbance history are secondary [34,35,36,37,38]. Therein, higher precipitation and shorter and less intense dry periods were associated with significantly higher tree growth rates, while weak or no relationships with soil nitrogen or plant available phosphorus were found [34]. The climatic variable mean annual precipitation often explains a large part of the observed variation in AGB or growth [35,38]; however, the variable climatological water deficit is deemed even more suitable for studying the effects of water availability on growth because it reflects both the duration and severity of water-limited conditions over the course of a year [39,40]. Indications that water availability often is a crucial factor controlling tree growth are further strengthened by previous reports of vastly increased growth in irrigated compared to non-irrigated plantations, particularly in water-limited tropical regions [41,42,43,44,45]. To our knowledge, no previous studies investigating effects of natural or artificial water supply or their interaction on the growth of M. dubia are available. However, such information is essential for further improving its management, e.g., with regard to optimized site selection or drought-adapted irrigation schemes.

M. dubia is particularly popular in South India, a region characterized by a tropical monsoon climate with a distinct seasonality and steep gradients in annual rainfall. On South Indian farms, we studied 186 M. dubia farmland woodlots between one and nine years in age and covering a rainfall gradient from 420 to 2170 mm year−1.

2. Study Region

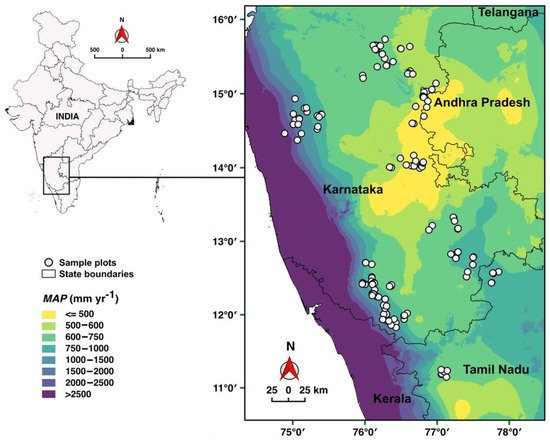

The studied woodlots were located in the South Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu (Figure 1). Tropical monsoon climate prevails in the region, with a rainy season from May to October and a dry season from November to April. Mean annual precipitation (MAP) increases from the interiors with around 400 mm year−1 towards the Western Ghats with more than 3000 mm year−1 (Figure 1). Mean annual temperature (MAT) ranges from 29.5 °C in the inland lowlands to 21.6 °C in the highlands (Ghats) [46]. The soils in the region are variable [47] and accommodate diverse vegetation formations ranging from open thorn scrub over wooded grasslands to closed forests [48,49]. The region has a long-standing history of diverse land-use practices; coffee, coconut, areca nut and rubber plantations dominate in the moist, humid and sub-humid zones, whereas rainfed and irrigated agriculture dominates in the dry lowland plains [50]. Today, forest cover in the region is about 14% [51].

Figure 1. Study region in South India and location of the 186 M. dubia woodlots. The sites span across a gradient in mean annual precipitation (MAP) ranging from 420 to 2170 mm year–1.

3. Study Sites and Plot Design

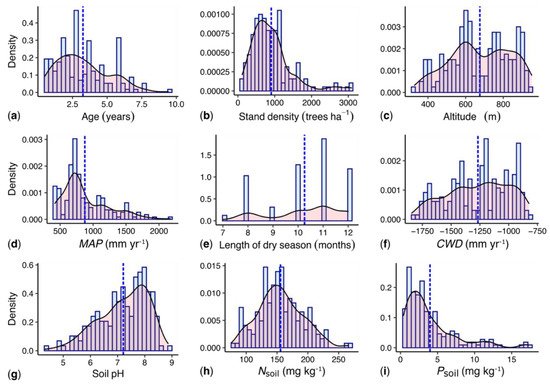

The woodlots ranged from approx. one to nine years in age; older stands were not found in the region. The woodlots covered a gradient in MAP from 420 to 2170 mm year−1 (Figure 2); M. dubia is commonly not grown at higher rainfall levels. The gradient encompasses four climatic zones (arid, semi-arid, dry-sub-humid and humid; zonation according to Trabucco and Zomer 2019 [52]). The plots were identified and located based on information from the Karnataka Forest Department, forestry colleges and research institutes, NGOs, nursery enterprises, media and farmers.

Figure 2. Key characteristics of the studied M. dubia woodlots. Histograms and kernel densities of selected key sites and management (a–c), climate (d–f) and soil variables (g–i) along the studied gradients. MAP: Mean annual precipitation; CWD: climatological water deficit; Nsoil: soil nitrogen content; Psoil: soil phosphorous content.

General land-use history and management information on each woodlot were raised through interviewing farmers with semi-structured questionnaires. All studied M. dubia woodlots were established on former agricultural land. To avoid early-stage failures of the woodlots, all interviewed farmers irrigated the seedlings for at least one growing season. Most farmers (66%) continued supplemental irrigation for more than one growing season, but with reduced irrigation frequencies (hereafter referred to as ‘irrigated’). A total of 34% moved to exclusively rainfed cultivation after the initial irrigation period (hereafter referred to as ‘non-irrigated’); MAP at all non-irrigated woodlots was higher than 670 mm year−1. In each woodlot, biometric data were collected within a 20 m × 20 m plot. The plots were established near the center of the woodlots to avoid edge effects, at locations typical for the average growth conditions (based on visual assessment and discussion with the owner).

4. Aboveground Biomass of M. dubia

In South India, the native M. dubia is a popular plantation species due to its versatile use, fast growth, straight boles and its ability to cope with different edaphic and climate conditions [25,26] (Figure 3). On farmland woodlots across large gradients in management, climate and soil conditions, our regression model predicts an average stand-level AGB of 93.8 Mg ha–1 for nine-year-old M. dubia stands. At this age, trees are commonly harvested, and we did not observe any older stands across the studied woodlots. Predictions from our regression model for a hypothetic landscape with a homogeneous distribution of M. dubia plantations across nine age classes (i.e., one to nine years in steps of one year, then immediate harvest and replanting) yield an average AGB stock of 44.1 Mg ha–1. Assuming a carbon content of AGB of approx. 50% [71], this corresponds to an average permanent aboveground carbon stock of 22.1 Mg ha–1. In comparison, dry forests in South India were reported to have aboveground carbon stocks of 37 to 116 Mg ha–1 [72,73,74]. Such carbon stock quantifications may be of interest for life cycle analysis of M. dubia products, carbon offset programs or other climate change mitigation mechanisms.

Figure 3. Fully leafed one-year-old M. dubia woodlot with MAP over 700 mm (a) and a leaf-shed four-year-old woodlot at MAP below 500 mm (b). M. dubia logs at an industrial yard for peeling veneers (c) and extracted veneers (d).

5. Growth Potential of M. dubia

Of central interest for short-rotation plantation species is their growth, i.e., their average annual AGBI over a typical rotation cycle. Based on the AGB estimate for an average nine-year old woodlot from our simple regression model, the mean AGBI across our study region is 10.4 Mg ha−1 year–1. This estimate falls within the range of values reported for four-year-old M. dubia plantations in South India (9.6 to 12.7 Mg ha−1 year−1, estimates derived in analogy to our study using DBH and height data [33]. The AGBI rate of M. dubia is comparable to or higher than those reported for several other popular plantation species across India. This includes reports from teak (Tectona grandis) of varying ages (2.6 to 16 Mg ha−1 year−1, [75,76]), five- to eleven-year-old Populus deltoides (6.3 to 16.4 Mg ha−1 year−1, [77,78]), four- to six-year-old Gmelina arborea (0.6 to 8.5 Mg ha−1 year−1, [79,80]), three- to ten-year-old Dalbergia sissoo (2.5 to 7.8 Mg ha−1 year−1, [41,77,81,82]) as well as from nine-year-old plantations of Casuarina equisetifolia (10.9 Mg ha−1 year−1), Pterocarpus marsupium (7.5 Mg ha−1 year−1), Ailanthus triphysa (4.6 Mg ha−1 year−1) and Leucaena leucocephala (2.6 Mg ha−1 year−1) [81]. Other studies on common plantation species reported higher AGBI (12.2 to 37.5 Mg ha−1 year−1) than we found for M. dubia, both for India [20,44,81,83,84] and other tropical countries [85,86,87,88]. However, these studies commonly examine only one or few sites. In contrast, our average M. dubia AGBI estimate is based on studying 186 woodlots across steep environmental gradients. At single sites in our study, AGBI rates of well over 20 Mg ha−1 year−1 were observed.

6. Controls of Biomass and Growth of M. dubia

A power-law growth curve represented the changes in AGB with increasing woodlot age well for the studied stands between one and nine years of age (Figure 3). Our findings are in line with several previous studies in monocultural short-rotation tree plantations showing similar relationships (e.g., [44,78,89,90]).

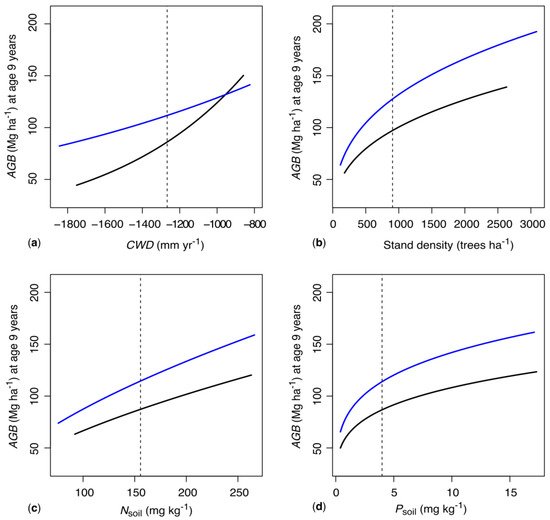

The multiple regression model (Table 1) explained 65% of the observed variance in stand-scale AGB. It indicates a key role of water availability for the growth of M. dubia. Therein, both natural (CWD) and artificial (irrigation) water supply have strong effects on AGB, and the effects of irrigation vary strongly along the studied CWD gradient (Figure 4a). The annual CWD was highly significant in the model (Table 1). Its standardized effect size on growth was 28% larger than that of irrigation and 72–150% larger than the effect sizes of Nsoil and Psoil. These results are in line with several previous studies reporting that the natural water availability is closely related to the growth of tropical trees, while soil conditions and further factors such as land-use history are often secondary [34,35,36,37,38].

Figure 4. Partial predictions of stand-level aboveground biomass (AGB, Mg ha–1) of harvest-ready, nine-year-old woodlots as influenced by key management, climate, and soil variables. Along the observed gradients in climatological water deficit (CWD) (a), stand density (b) and soil nitrogen (Nsoil) (c) and phosphorus (Psoil) (d), AGB is predicted separately for irrigated (blue lines) and non-irrigated woodlots (black lines) from the multiple model. All variables other than tree age (kept at nine years) and the respective displayed variable were kept at their average values (dashed vertical lines). Predictions were computed for the observed ranges of CWD, stand density, Nsoil and Psoil in the irrigated and non-irrigated woodlots, respectively.

Table 1. Results of the multiple regression model for stand-level aboveground biomass (AGB) using stand age and preselected key management, climate and soil variables and their interactions as predictors. AGB and predictors (except irrigation, CWD) were natural log-transformed. Except for the main predictor, age, numeric variables were scaled by their standard deviations and centered around zero. The model explains 65% of the variance in AGB across the studied woodlots (F-statistic 41.6 on 8 and 177 DF, p < 0.001). CWD: climatological water deficit; Nsoil: soil nitrogen content; Psoil: soil phosphorus content.

| Parameters | Estimate | SE | t Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 4.52 | 0.32 | 14.27 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.45 | 0.09 | 16.28 | <0.001 |

| Stand density | 0.54 | 0.29 | 1.84 | 0.06 |

| Age: Stand density | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.83 | 0.40 |

| Age: Irrigation (irrigated) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.67 | 0.09 |

| Age: CWD | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.62 | <0.01 |

| Age: Nsoil | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.62 | 0.10 |

| Age: Psoil | 0.05 | 0.02 | 2.89 | <0.01 |

| Age: CWD: Irrigation (irrigated) | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.37 | 0.17 |

Likewise, the observed strong positive influence of irrigation of AGB growth is in line with several previous studies in tree plantations [41,42,43,44]. Our model goes a step further in including an interaction between natural and artificial water supply, which showed an expected decreasing benefit of irrigation as the natural water availability increases (i.e., as CWD becomes less negative). This results in similar AGB predictions for mature irrigated and non-irrigated woodlots at the wet end of the studied CWD gradient past approx. –1000 mm year–1, while an almost twice as high AGB is predicted for irrigated woodlots at the dry end at around –1800 mm year–1 (Figure 4a). Such information is essential for further optimizing the growth of M. dubia through enhanced site selection and water management schemes.

Notably, both interaction terms involving irrigation were associated with substantial uncertainties and were thus only marginally significant and non-significant, respectively, in the multiple model (Table 1). There are several potential reasons for this: Firstly, there is uncertainty arising from a lack of information on irrigation frequency and volume, as irrigation only appears as a categorical variable. Secondly, first- and second-order interaction terms in general have much higher uncertainties than main effects. Thirdly, irrigation is a conscious and complex management decision by the farmers likely already taking into account local conditions and planting densities, which are not considered in our relatively simplistic model. Finally, the irrigation effect refers to a woodlot of average characteristics, i.e., at average CWD, while differences at the dry end of the gradient would likely be more pronounced. Despite such limitations, our model does confirm a key role of the water supply for the AGB growth of tropical trees, in our case for M. dubia in South India: growth is strongly constrained at the dry end of the studied CWD gradient, but can be increased considerably by irrigation.

Within the studied stand density range (116 to 3086 trees ha–1, 67% between 116 and 1000 trees ha–1), the model showed a marginally significant positive effect of stand density on initial AGB and a negative effect of stand density on AGB growth; the latter was non-significant in our model (Table 1). As for irrigation, a potential explanation for the lack of significant growth effects is that stand density is a management decision by farmers that is likely based on prior knowledge on recommended planting distances under the respective site conditions. For mature, non-irrigated woodlots at average CWD (–1293 mm year–1) and of average soil characteristics, increases in stand density lead to pronounced increases in predicted AGB until a stand density of approx. 1000 trees ha–1; higher densities result in under-proportional further increases in AGB (Figure 4b). Our results of increasing stand-scale AGB with increasing stand densities up to over 3000 trees ha–1 somewhat contrast the results from a previous experimental study on M. dubia in South India, which showed slightly higher growth at lower stand densities (below 833 trees ha–1) compared to higher stand densities (1000–2500 trees ha–1) [33]. However, the study was based on few spatial replicates, the observed differences were not examined statistically and the stands were only four years old at the time of study. Overall, the influence of the stand density of AGB growth of M. dubia is still associated with too many uncertanties to derive clear management recommendations and requires further experimental studies. Our results do, however, suggest that M. dubia can achieve considerable stand-scale growth over a relatively broad range of stand densities, which gives farmers flexibility with regard to producing wood of variable, locally desired dimensions.

The effect of nutrient availability on AGB growth was small compared to the effect of water availability (Table 1). Our model contained Nsoil and Psoil as predictors for soil nutrient effects, as these are the two macronutrients that are commonly found to limit plant growth [91,92]. Nsoil varied three-fold across the studied woodlots, and Psoil varied forty-fold. While the relatively small positive effect of Nsoil on AGB was non-significant (p = 0.107), the stronger positive effect of Psoil was highly significant, indicating partially pronounced soil phosphorus limitations in our study region. Our result of a rather moderate influence of soil nutrient status on AGBI is in line with several previous studies on tropical tree species; exceptions are typically only found on severely nutrient-limited sites with drastically reduced growth [34,91,92,93]. This is also indicated by the distinctly non-linear effect of Psoil on AGB of mature, non-irrigated woodlots: while increases in Psoil from near zero to approx. 5 mg kg–1 result almost in a doubling of AGB, further increases in Psoil are associated with relatively small increases in AGB (Figure 4d). This suggests that there may be room for further growth optimization by enhanced site selection and by (moderate) fertilizer application on nutrient-poor sites.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/f12121675

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!