The so-called paper-based analytical devices (PADs) have arisen as an efficient, affordable, user-friendly, rapid, and equipment-free technology that is available to citizens. The development of PADs in areas such as clinical diagnostics, food safety and environmental monitoring, etc., as well as fabrication methods, target analytes and analytical performance, has been extensively reviewed during the last decade, with the scientific community showing great interest toward these appealing analytical approaches.

- paper-based analytical devices

- mercury

- nanomaterials

1. Introduction

Hg can reach aquatic ecosystems through point-source discharges or atmospheric deposition. Thus, volcanic eruptions and the solubilization of rocks, soils and sediments are among the most relevant natural sources [1]. Anthropogenic sources such as small-scale gold mining, the combustion of solid fuels (coal, lignite, wood), chlor-alkali, paper, paint and pharmaceutical industries, dental implants, agriculture products (germicides, pesticides, etc.); although mostly restricted in many countries, they still contribute to increasing the Hg levels in the environment [2]. Therefore, stringent analytical controls are needed to assess the contamination of environmental samples with Hg.

Hg can be found in different environmental compartments as a variety of species; each one has different behavior, and hence, toxicological properties, bioavailability and environmental impact depend on its physicochemical forms (i.e., speciation). Thus, in natural waters, the main forms in which Hg can be present are elemental mercury (Hg 0), inorganic mercury ( Hg 2+ ) and organic mercury, i.e., CH 3-Hg + and (CH 3) 2Hg. Biomagnification of Hg through the food chain may occur as a result of the high hydrophobicity of organic Hg species. In this way, Hg can accumulate in some fish by a factor of ca. 10 6 in respect to the concentration levels in the aquatic environment [3].

For the determination of Hg at the (ultra)trace level, conventional instrumentation is typically used in central labs on a routine basis, such as cold vapor-atomic absorption spectrometry (CV-AAS) [4], cold vapor-atomic fluorescence spectrometry (CV-AFS) [5], electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry (ETAAS) [6], inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) [7] and total reflection X-ray fluorescence (TXRF) [8]. While these techniques provide adequate sensitivity and precision, they require suitable sampling, preservation procedures, sample pretreatment and a fully controlled laboratory environment, which makes it difficult to extend their application for on-field analysis [9]. In addition, problems may arise in the sampling and sample preparation procedures prior to the determination of Hg at the (ultra)trace level by conventional analytical techniques, which can lead to systematic errors and unacceptable analytical uncertainties [3].

In recent years, several trends have emerged concerning the analytical control of environmental pollutants, such as a remarkable increase in the miniaturization, portability and greenness of analytical approaches, thus facilitating on-site measurements [10]. The latter possibility is particularly interesting, since it could allow real time measurements without the need for preservation, transport and sample storing prior to analysis by a conventional technique. Further appealing features include the possibility of performing temporally and spatially discriminated analysis and the access to remote sites so that the source of pollutants, their distribution and environmental impact can be more easily assessed [11].

2. Development of Paper-Based Analytical Devices for the Detection of Mercury

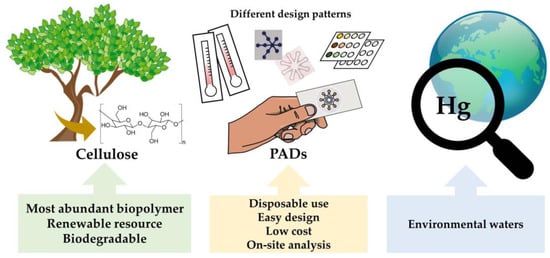

Lab-on-chip (LOC) technologies have emerged as miniaturized, low cost and fast analytical approaches allowing a decrease in sample, reagents and energy consumption through the integration of typical stages of bench-scale laboratories within a single device [12]. From the standpoint of green chemistry, the use of cellulose instead of typical substrates employed in LOC systems such as polymers, silicon or glass represent a significant step forward. Cellulose-based materials have been established in the last years as efficient, versatile and universal biopolymers for the design of novel microscale analytical systems [13] ( Figure 1 ). As compared to other scaffolds used for building sensors and microfluidic devices, cellulose is a biodegradable, biocompatible, hydrophilic and highly porous material. In addition, it possesses high capillarity, and a large variety of recognition elements can be immobilized for sensing. When used along the widespread colorimetric transduction, white color is excellent to achieve good analytical performance [14].

The so-called paper-based analytical devices (PADs) have arisen as an efficient, affordable, user-friendly, rapid, and equipment-free technology that is available to citizens. The development of PADs in areas such as clinical diagnostics, food safety and environmental monitoring, etc., as well as fabrication methods, target analytes and analytical performance, has been extensively reviewed during the last decade [15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29], with the scientific community showing great interest toward these appealing analytical approaches.

Under the general term ‘paper-based analytical devices’ (PADs), two systems can be distinguished, i.e., microfluidic paper-based analytical devices’ (μ-PAD), where a fluidic network is built in the paper substrate, and ‘paper-based assay devices’, also known as ‘paper-based sensors’ or ‘spot tests’, where the sample is directly deposited onto the paper surface. First systems, introduced by Whitesides for the first time [30], include different configurations, such as two-dimensional (2D), three-dimensional (3D) and distance-based devices. In these microfluidic devices, the sample and reagents are transported to the detection zone by capillarity. Second designs derive from the classical qualitative analysis tests, where the detection of inorganic cations and anions could be performed on filter paper using suitable colorimetric and fluorescent reagents [31]. In paper-based assay devices, the sample comes directly into contact with the receptor, which remains stationary on the cellulose scaffold.

In this review, we provide an overview on the state of the art of PADs for the detection of Hg in environmental samples, their main shortcomings and future prospects.

3. Paper-Based Sensors Integrated with Organic Chromogenic/Fluorogenic Receptors for Hg Detection

Several chromogenic/fluorogenic reagents have been used as recognition elements for the detection of Hg(II) in both paper-based sensors [32][33][34][35][36][37][38] and μ-PADs [39][40][41][42] ( Table 1 ). In a few cases, multiplexed systems for the detection of other metal ions have been reported [41][42]. An array of paper strips has also been designed for the detection of several metals, including Hg [43]. Environmental samples analyzed mostly include several types of waters, yet applications to biological samples, soils and creams have also been described [32][39][40]. With some exceptions where inorganic chromogenic species are involved [32][40], the most reported applications use organic chromogenic reagents for analyte recognition.

| Material | Type of PAD | Recognition Element | Signal Readout |

Sample/Matrix | LOD (ppb) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 MM Whatman chromatography paper |

Paper-based sensor | CuI | Scanner | Fish | 7 (ng/g) | [32] |

| Cellulose | Paper-based sensor | bis(ferrocenyl) azine | Naked eye | Aqueous media | 104 | [33] |

| Porous silica matrix onto cellulose |

Paper-based sensor * | Rhodamine B thiolactone | Flatbed scanner and naked eye |

Water | 0.24 (Scanner) | [34] |

| Filter paper | Paper-based sensor | Rhodamine appended vinyl ether |

Naked eye | Drinking water Tap water |

27.2 (in solution) 104 (paper strip) |

[35] |

| Whatman paper | Paper-based sensor | Ir complex (Phosphorescent) |

Naked eye | --- | 3.56 (fluorimetry) | [36] |

| Cellulose paper | Paper-based sensor (Hg, I, Zn) |

Calix[4]arene (fluorescent) |

Digital camera (UV irradiation) |

Wastewater | 0.58 (fluorimetry) | [37] |

| Filter paper | Paper-based sensor | Tetrahydrophenazine-based Fluorophore |

Digital camera | --- | 8 × 103 (neutral pH) 3 × 103 (pH 1.6–2.3) |

[38] |

| Filter paper | μ-PAD | Dithizone | Naked eye | Whitening cream | 930 | [39] |

| Whatman No. 4 filter paper |

μ-PAD | HgI42− complex | Digital camera | Contaminated soil and water |

2 × 104 | [40] |

| Whatman grades No. 1 and 4 |

μ-PAD (Hg, Pb, Cr, Cu, Fe) |

Three indicators (ligands) | Digital camera | Waters | 20 | [41] |

| Whatman No. 1 paper | μ-PAD (Cu, Co, Ni, Mn, Hg) |

Dithizone (for Hg) | Scanner | Drinking, pond and tap water |

200 (scanner) ca. 104 (naked eye) |

[42] |

| Whatman grade No. 1 filter paper |

Array paper strip (for Hg, Ag, Cu) |

5 indicators (18 formulations) |

Flatbed scanner | Pond water | 38 (Hg) | [43] |

While naked eye detection is carried out in many PADs, devices related to information and communication technologies (ICTs) such as digital cameras, scanners, smartphones, etc., have been mostly used for capturing images on PADs. Further image processing is employed for measuring color intensity. LODs at the ppm level are generally reported for many applications of PADs concerning Hg detection, with the exception of approaches involving any kind of preconcentration (e.g., [34]). In a significant number of papers, LODs corresponding to the use of receptors in a solution followed by detection with a conventional instrument are provided (e.g., [36][37]).

Patil and Das [35] described a selective colorimetric and fluorometric chemosensor based on a rhodamine appended vinyl ether (RDV) probe for Hg(II) recognition. Paper strips were employed by immersing filter paper into a RDV solution. Although an LOD of 136 nM was obtained using a solution assay, the paper strip was useful for Hg detection at the ppm level (above ca. 10 ppm).

The immobilization of an infrared fluorescence protein (IFP) and its chromophore biliverdin (BV) has been applied by Gu et al. [44] for Hg(II) detection. An LOD of less than 50 nM was achieved. The IFP/BV sensor can serve as a tool for the detection of Hg in living organisms or tissues. A protein-hydrogel-based paper assay was also used for the immobilization of IFP onto paper strips for detection of Hg(II). Enrichment by multiple addition/drying steps onto the paper strip allows detection at the 20 nM level.

4. Paper-Based Analytical Devices Integrated with Nanomaterials as Receptors for Hg Detection

When the light of appropriate frequency interacts with some metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag, Cu), a collective oscillation of electrons at their conduction bands occurs, which is the basis for the surface plasmon resonance (SPR) phenomenon [45]. When the dimensions of metal nanoparticles are lesser than the radiation wavelength, the phenomenon is known as ‘localized surface plasmon resonance’ (LSPR). Absorption of radiation takes place when light has the same frequency as oscillations. The localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) absorption bands are characteristics of the metal involved in the colloidal solution, i.e., it depends on size, shape, interparticle distance, composition of the nanoparticles and refractive index of the surrounding medium. Thus, the colors displayed by colloidal solutions of AuNPs, AgNPs and CuNPs are pink, yellow and red, respectively. More interestingly, these NPs possess much higher molar extinction coefficients as compared to chromogenic agents. The molar extinction coefficients corresponding to the LSPR absorption bands of AuNPs and AgNPs are 10 8 and 10 10 M −1 cm −1 , respectively. Typically, the wavelength of the LSPR band is largely affected by the size and chemical environment surrounding the nanoparticles, such as the presence of capping agents, formation of amalgams, species adsorbed, etc. Noble metal nanoparticles have been widely applied for the detection of metal ions [46].

A paper-based sensor was developed by Apilux et al. [47] for the detection of Hg(II) in waters using AgNPs and silver nanoplates (AgNPls). The color change of AgNPls on a paper test in the presence of Hg(II) can be monitored by the naked eye. A quantitative assay can be accomplished following image capture by a digital camera along with an image processing software to yield an LOD of 0.12 ppm. Upon the accumulation of Hg on paper through multiple applications of 2 μL, an LOD of 2 ppb can be achieved. The color change of AgNPs and AgNPls can be ascribed to changes in size and shape. A sensing mechanism based on the redox reaction between Hg(II) and AgNPls was proposed.

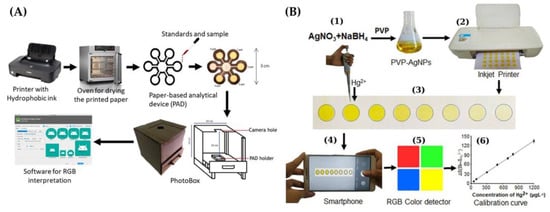

An inkjet-printed paper-based colorimetric sensor with AgNPs, along with a smartphone and RGB color detection, was developed by Shrivas et al. [48] ( Figure 2 B). A color change from yellow to colorless was observed in the presence of Hg(II). A reaction mechanism responsible for the color change was proposed as a result of the interaction of Hg(II) and a PVP stabilizing agent employed as a capping agent for AgNPs, and an oxidation of Ag 0 to Ag + . An LOD of 10 ppb was obtained.

Metal nanoclusters (NCs) made of Au, Ag, Cu, etc., with a size of less than 2 nm, does do not undergo the SPR effect, unlike metal nanoparticles (NPs), but they possess strong luminescence [50].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/s21227571

References

- Raj, D.; Maiti, S.K. Sources, toxicity, and remediation of mercury: An essence review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 566.

- Mercury Emissions: The Global Context. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/mercury-emissions-global-context (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Leopold, K.; Foulkes, M.; Worsfold, P. Methods for the determination and speciation of mercury in natural waters: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 663, 127–138.

- Kozaki, D.; Mori, M.; Hamasaki, S.; Doi, T.; Tanihata, S.; Yamamoto, A.; Takahashi, T.; Sakamoto, K.; Funado, S. Simple mercury determination using an enclosed quartz cell with cold vapour-atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 1106–1109.

- da Silva, M.J.; Paim, A.P.S.; Pimentel, M.F.; Cervera, M.L.; de la Guardia, M. Determination of total mercury in nuts at ultratrace level. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 838, 13–19.

- Guerrero, M.M.L.; Cordero, M.T.S.; Alonso, E.V.; Pavón, J.M.C.; de Torres, A.G. High resolution continuum source atomic absorption spectrometry and solid phase extraction for the simultaneous separation/preconcentration and sequential monitoring of Sb, Bi, Sn and Hg in low concentrations. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2015, 30, 1169–1178.

- Chen, Y.; He, M.; Chen, B.; Hu, B. Thiol-grafted magnetic polymer for preconcentration of Cd, Hg, Pb from environmental water followed by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry detection. Spectrochim. Acta Part B 2021, 177, 106071.

- Romero, V.; Gryglicka, M.; de la Calle, I.; Lavilla, I.; Bendicho, C. Ultrasensitive determination of mercury in waters via photochemical vapor deposition onto quartz substrates coated with palladium nanoparticles followed by total reflection X-ray fluorescence analysis. Microchim. Acta 2016, 183, 141–148.

- Lim, J.W.; Kim, T.-Y.; Woo, M.-A. Trends in sensor development toward next-generation point-of-care testing for mercury. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 183, 113228.

- Pena-Pereira, F.; Bendicho, C.; Pavlović, D.M.; Martín-Esteban, A.; Álvarez, M.D.; Pan, Y.; Cooper, J.; Yang, Z.; Safarik, I.; Pospiskova, K.; et al. Miniaturized analytical methods for determination of environmental contaminants of emerging concern: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1158, 238108.

- Botasini, S.; Heijo, G.; Méndez, E. Toward decentralized analysis of mercury (II) in real samples. A critical review on nanotechnology-based methodologies. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 800, 1–11.

- Keçili, R.; Hussain, C.M. Green micro total analysis systems (G μTAS) for environmental samples. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2021, 30, e00128.

- Fu, L.-M.; Wang, Y.-N. Detection methods and applications of microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 107, 196–211.

- López-Marzo, A.M.; Merkoçi, A. Paper-based sensors and assays: A success of the engineering design and the convergence of knowledge areas. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3150–3176.

- Almeida, M.I.G.S.; Jayawardane, B.M.; Kolev, S.D.; McKelvie, I.D. Developments of microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs) for water analysis: A review. Talanta 2018, 177, 176–190.

- Meredith, N.A.; Quinn, C.; Cate, D.M.; Reilly, T.H.; Volkens, J.; Henry, C.S. Paper-based analytical devices for environmental analysis. Analyst 2016, 141, 1874–1887.

- Aydindogan, E.; Celik, E.G.; Timur, S. Paper-based analytical methods for smartphone sensing with functional nanoparticles: Bridges from Smart Surfaces to Global Health. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 12325–12333.

- Yang, Y.; Noviana, E.; Nguyen, M.P.; Geiss, B.J.; Dandy, D.S.; Henry, C.S. Paper-based microfluidic devices: Emerging themes and applications. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 71–91.

- Nery, E.W.; Kubota, L.T. Sensing approaches on paper-based devices: A review. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 7573–7595.

- Liana, D.D.; Raguse, B.; Gooding, J.J.; Chow, E. Recent advances in paper-based sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 11505–11526.

- Kaneta, T.; Alahmad, W.; Varanusupakul, P. Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices with instrument free detection and miniaturized portable detectors. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2019, 54, 117–141.

- Morbioli, G.G.; Mazzu-Nascimento, T.; Stockton, A.M.; Carrilho, E. Technical aspects and challenges of colorimetric detection with microfluidic paper-based analytical devices (μPADs)-A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 970, 1–22.

- Cate, D.M.; Adkins, J.A.; Mettakoonpitak, J.; Henry, C.S. Recent developments in paper-based microfluidic devices. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 19–41.

- Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Tian, L.; Wang, Z. Portable and smart devices for monitoring heavy metal ions integrated with nanomaterials. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 98, 190–200.

- Ullah, N.; Mansha, M.; Khan, I.; Qurashi, A. Nanomaterial-based optical chemical sensors for the detection of heavy metals in water: Recent advances and challenges. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 100, 155–166.

- Sriram, G.; Bhat, M.P.; Patil, P.; Uthappa, U.T.; Jung, H.-Y.; Altalhi, T.; Kumeria, T.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Pai, R.K.; Madhuprasad; et al. Paper-based microfluidic analytical devices for colorimetric detection of toxic ions: A review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2017, 93, 212–227.

- Noviana, E.; Ozer, T.; Carrell, C.S.; Link, J.S.; McMahon, C.; Jang, I.; Henry, C.S. Microfluidic paper-based analytical devices: From design to applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11835–11885.

- Ozer, T.; McMahon, C.; Henry, C.S. Advances in paper-based analytical devices. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2020, 13, 85–109.

- Bendicho, C.; Lavilla, I.; Pena-Pereira, F.; de la Calle, I.; Romero, V. Nanomaterial-integrated cellulose platforms for optical sensing of trace metals and anionic species in the environment. Sensors 2021, 21, 604.

- Martinez, A.W.; Phillips, S.T.; Butte, M.J.; Whitesides, G.M. Patterned paper as a platform for inexpensive, low-volume, portable bioassays. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1318–1320.

- Feigl, F.; Anger, V. Spot Tests in Inorganic Analysis, 6th ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1972.

- Paciornik, S.; Yallouz, A.V.; Campos, R.C.; Gannerman, D. Scanner image analysis in the quantification of mercury using spot-tests. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 156–161.

- Díez-Gil, C.; Caballero, A.; Ratera, I.; Tárraga, A.; Molina, P.; Veciana, J. Naked-eye and selective detection of mercury (II) ions in mixed aqueous media using a cellulose-based support. Sensors 2007, 7, 3481–3488.

- Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Yana, X.; Guan, Y. Naked-eye sensor for rapid determination of mercury ion. Talanta 2013, 116, 563–568.

- Patil, S.K.; Das, D. A nanomolar detection of mercury(II) ion by a chemodosimetric rhodamine-based sensor in an aqueous medium: Potential applications in real water samples and as paper strips. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2019, 210, 44–51.

- Ponram, M.; Balijapalli, U.; Sambath, B.; Iyer, S.K.; Kakaraparthi, K.; Thota, G.; Bakthavachalam, V.; Cingaram, R.; Sung-Ho, J.; Sundaramurthy, K.N. Inkjet-printed phosphorescent Iridium(III) complex based paper sensor for highly selective detection of Hg2+. Dyes Pigm. 2019, 163, 176–182.

- Sutariya, P.G.; Soni, H.; Gandhi, S.A.; Pandya, A. Luminescent behavior of pyrene-allied calixarene for the highly pH-selective recognition and determination of Zn2+, Hg2+ and I− via the CHEF-PET mechanism: Computational experiment and paper-based device. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 9855–9864.

- Ergun, E.G.C. Three in one sensor: A fluorometric, colorimetric and paper based probe for the selective detection of mercury(II). New J. Chem. 2021, 45, 4202–4209.

- Cai, L.; Fang, Y.; Mo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M. Visual quantification of Hg on a microfluidic paper-based analytical device using distance-based detection technique. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 085214.

- Nashukha, H.L.; Sitanurak, J.; Sulistyarti, H.; Nacapricha, D.; Uraisin, K. Simple and equipment-free paper-based device for determination of mercury in contaminated soil. Molecules 2021, 26, 2004.

- Idros, N.; Chu, D. Triple-indicator-based multidimensional colorimetric sensing platform for heavy metal ion detections. ACS Sens. 2018, 3, 1756–1764.

- Kamnoet, P.; Aeungmaitrepirom, W.; Menger, R.F.; Henry, C.S. Highly selective simultaneous determination of Cu(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Hg(II), and Mn(II) in water samples using microfluidic paper-based analytical devices. Analyst 2021, 146, 2229–2239.

- Liu, L.; Lin, H. Paper-based colorimetric array test strip for selective and semiquantitative multi-ion analysis: Simultaneous detection of Hg2+, Ag+, and Cu2+. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 8829–8834.

- Gu, Z.; Zhao, M.; Sheng, Y.; Bentolila, L.A.; Tang, Y. Detection of mercury ion by infrared fluorescent protein and its hydrogel-based paper assay. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 2324–2329.

- Li, M.; Cushing, S.K.; Wu, N. Plasmon-enhanced optical sensors: A review. Analyst 2015, 140, 386–406.

- Yu, L.; Song, Z.; Peng, J.; Yang, M.; Zhi, H.; He, H. Progress of gold nanomaterials for colorimetric sensing based on different strategies. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2020, 127, 115880.

- Apilux, A.; Siangproh, W.; Praphairaksit, N.; Chailapakul, O. Simple and rapid colorimetric detection of Hg(II) by a paper-based device using silver nanoplates. Talanta 2012, 97, 388–394.

- Monisha; Shrivas, K.; Kant, T.; Patel, S.; Devi, R.; Dahariya, N.S.; Pervez, S.; Deb, M.K.; Rai, M.K.; Rai, J. Inkjet-printed paper-based colorimetric sensor coupled with smartphone for determination of mercury (Hg2+). J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125440.

- Firdaus, M.L.; Aprian, A.; Meileza, N.; Hitsmi, M.; Elvia, R.; Rahmidar, L.; Khaydarov, R. Smartphone coupled with a paper-based colorimetric device for sensitive and portable mercury ion sensing. Chemosensors 2019, 7, 25.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, E. Metal nanoclusters: New fluorescent probes for sensors and bioimaging. Nano Today 2014, 9, 132–157.