Angiogenesis can be revisited as a complex biological process with numerous compensatory pathways that can be activated, challenging the discovery of predictive biomarkers, since the cancer microenvironment and the complex milieu are difficult to classify and several actors are simultaneously shaping the key pro-angiogenic ecosystem. Bevacizumab represents the archetypic example of the various mechanisms of action, which may differ between cancer types and chemotherapy, unveiling the multifaceted functions in driving regression of existing tumor vasculature, halting new vessel growth, shaping the anti-permeability of surviving vasculature, and priming vessel normalization and co-option. Unfortunately, a poor correlation between response and survival exists, and the effects are mainly limited to PFS, and from a clinical trials standpoint, cross-over events at progression make identification of response criteria and biomarkers difficult.

- angiogenesis

- anti-angiogenesis

- bevacizumab

- drug resistance

- VEGF

1. Introduction

Several anti-angiogenic drugs have been approved for cancer treatment, alone or in combination with other anti-tumoral agents, and anti-angiogenic therapy is essentially an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or anti-VEGF-receptor (VEGFR) therapy [1]. The first anti-angiogenic drug, bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF-A monoclonal antibody, was approved for the treatment of previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancers in combination with chemotherapy [2]. Ranibizumab is a humanized antibody based on a single antigen-binding site (Fab) derived from bevacizumab, but with a higher VEGF-A binding activity. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are additional anti-angiogenic drugs, which interfere with VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, platelet derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFRs), and Tie2 signaling [3]. VEGF-trap protein aflibercept, obtained by fusion of VEGF binding domain of VEGFR-1 and R-2, which acts as a ‘VEGF ligand trap’, has been approved for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer [4].

Anti-angiogenic drugs lead to an increase in patient’s overall survival (OS) in the range of weeks to months and a 3–6-month increase in progression-free survival (PFS), followed by relapse in tumor angiogenesis and growth. Discontinuation of the therapy is the principal factor responsible for the ineffectiveness of the anti-angiogenic therapies [5]. In fact, when VEGF-targeted therapies are discontinued, tumor vasculature is rapidly re-established [6], whereas continuation of bevacizumab treatment is associated with an increase in OS [7].

Angiogenesis inhibitors are responsible for metastasis formation and reduced delivery of chemotherapeutic agents, as a consequence of decrease of tumor vasculature. Increased invasiveness is secondary to enhanced expression of angiogenic cytokines or recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), favoring the formation of a pre-metastatic niche [8][9][10]. Clear cell renal carcinoma (CCRC) cells and glioblastoma multiforme cells show a high metastatic potential after treatment with bevacizumab and VEGF inhibition [11][12][13].

2. Vascular Normalization and Tumor Hypoxia

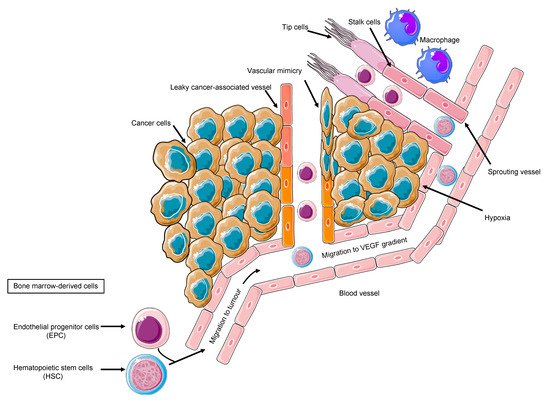

VEGF inhibition normalizes tumor vasculature, decreasing vascular permeability and enhancing delivery of oxygen and drugs to intratumoral sites [14]. Vascular homeostasis is transiently restored during the first days of therapy. The improvement in tumor oxygenation takes place in the last 2–4 days after anti-VEGF treatment [14]. Hypoxia re-increases, inducing systemic secretion of other angiogenic cytokines, selects more malignant cells, able to grow in hypoxic conditions, and stimulates β1 integrin expression, a marker of resistance to cancer treatment [15]. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) plays a critical role in resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies and is a survival factor used by cancer cells in a condition of oxygen deprivation. Moreover, HIF triggers epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis [16]. Invasiveness is increased as a consequence of the production of pro-migratory proteins, including stromal cells derived factor-1 alpha (SDF-1α), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and pro-invasive extracellular matrix proteins [17][18]. Circulating EPCs move to hypoxic sites and contribute to the generation of new blood vessels, and the inhibition of VEGF prevents the mobilization of EPCs to the tumor site [19][20]. Hypoxia triggers the differentiation of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells to M2-pro-angiogenic tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), the recruitment of EPCs, genetic instability in tumor endothelial cells, and the selection of more invasive metastatic tumor cell clones, resistant to anti-angiogenic agents [21][22][23].

3. Role of Inflammatory Cells, Endothelial Cells, and Tumor Cells

TAMs and tumor associated fibroblasts (TAFs) are both involved in resistance to anti-VEGF agents. Blocking TAM recruitment is the winning strategy to overcome resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Both TAMs and TAFs promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through the release of growth factors and proteases. Tumors refractory to anti-VEGF therapy display an increased number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [24]. In addition to tumor cells, tumor endothelial cells also undergo epigenetic modifications involved in resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies [25]. Furthermore, the effect that the anti-VEGF treatment has on the cancer cell itself has been largely ignored and only recently has been receiving the attention it deserves. Studies like the one from Luo and co-workers [26] demonstrate a direct effect of VEGF on the actual cancer cell rather than the vasculature, although this is something not taken into account so far in clinical trials. The importance of VEGF is further supported by the findings that, in some cases, tumors cells can become more aggressive after treatment with bevacizumab. This is, for example, the case with human glioma cells in which bevacizumab treatment induces invasion through the activation of the beta catenin pathway [27]. Moreover, bevacizumab-treated glioblastoma patients have an increased relapse in comparison to bevacizumab-untreated patients, linked to an upregulation of c-MET and phospho-c-MET [28].

4. Pleiotropic Role of VEGF in Angiogenesis, Inflammation, and Immunity

Tumor cells, the secreted soluble factors the interstitial stroma and extracellular matrix, pericytes, and endothelial cells represent a complex neighborhood in which a vicious cycle develops, acting as a pro-angiogenic reservoir. The endothelial cells are main actors on the angiogenic field, expressing a plethora of tyrosine kinase receptors that trigger proliferation, migration, and differentiation signals [29]. Costa et al. uncovered Int-2 oncogene as an angiogenesis inductor [30] and prompted further studies on additional mechanism, including VEGF [31]. VEGF family comprises VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, VEGF-E, and VEGF-F. VEGFR-2, also known as placental growth factor (PGF), is the main signal transducer and activates the main mechanism of PI3K, MAPK, IP3, and eNOS, which imprint one of the main features of malignant angiogenesis: the vasodilatation with endothelial detachment paralleling the cellular dynamics alteration [32]. The eNOS activation and NO production explain one of the major adverse events of anti-angiogenic treatment, namely the arterial hypertension, due to the decreased NO production. Conversely, VEGF production is related to vasodilation; VEGFR-2 is also related to cell survival and migration, and VEGFR-1 is additionally related to vascular stabilization, whereas VEGFR-3 is much more related to lymphangiogenesis [32]. By looking into the cellular system and compartmentalization for cell motility, it is important to highlight that an anaerobic metabolism is developed, and the proliferating endothelial cells (tip cell) trigger the sprouting angiogenesis via motile filopodia anchored to an extracellular matrix, attracting the cells through a VEGF gradient. Bystander cells suffice for an integrated system (stalk cell) while the cancer cell enhances the glycolytic activity supporting its migratory activity [33]. Thus, the actors on the scene are the neoplastic cells, the tip cells, rapidly migrating, the stalk cells, with supporting function, and the quiescent phalanx cells from which this structure is sprouting [33], tip and stalk cells being the most responsive to VEGF and its receptor VEGFR-2. The tumor vascular pattern largely differs from the normal vascular one in terms of morphology due to an abnormal vascular pattern of growth in which the blood and nutrient flow is absolutely aberrant, driving ischemia and abnormal solute and drugs delivery as demonstrated by VEGF expression tumor imaging performed with [34] Zr-Bevacizumab, with a decay in the drug concentration in 168 h. Contrariwise, as a proof of concept, VEGF within the tumor site is high. Imaging of VEGFR-2 expression addressed with [35] CU-DOTA-VEGF121 paralleled VEGF expression behavior in vivo models [36]. Remarkably, the role of hypoxia and VEGF in cancer is multifaced; nonetheless, in a hypoxic tumor, an overproduction of VEGF exerts an inhibitory effect on the dendritic cell and a stimulatory effect on the tumor-associated macrophages and on MDSCs, boosting Treg lymphocytes. Therefore, the result is an aberrant vasculogenesis within an immune-permissive niche [37] ( Figure 1 ).

The expression of angiogenic factors in gastrointestinal cell lines behaves as an archetype of the spectrum of a new vessel-sustaining phenotype. Across the plethora of pro-angiogenic molecules, VEGF largely predominates over PIGF, interleukin-8 (IL-8), and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) [38]. Remarkably, one of the paramount features of the tumor angiogenesis is the presence of precursors progenitors within the newly formed vessels expressing VEGFR-2. EPCs promote angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma [39]. Ligand neutralization, antibody targeting extracellular domain of VEGFR, and small molecules’ tyrosine kinase inhibitors are valuable strategies [40]. However, the parameters involved in the dynamics of blood flow are crucial in order to modulate and normalize the pathological vicious cycle of angiogenesis. Amid the cancerous vascularization, shunts are predominant over perfusion, due to a high interstitial pressure halting the soluble factors diffusion within the tumor. Therefore, allowing a normalized perfusion and restoring the angiogenic homeostasis are optimal activity markers [41]. Moreover, a markedly elevated interstitial fluid pressure in human tumors and normal tissues decreases the drug effect [42]. Among the tumor diseases, the stronger rationale behind the use of an antiangiogenic therapy in case of kidney tumors is due to VHL gene mutation [11][43]; nonetheless, in gastric cancer, HIF-1 overproduction boosts pro-angiogenic factor production [44]. Indeed, gastric cancer represents an ideal model to discuss anti-angiogenic approaches’ challenges in oncology. VEGF and VEGFR are significant molecular targets in gastric cancer [45][46][47]. Furthermore, VEGF and PDGF production in gastric cancer is expressed in the different subtypes [48], holding biological implications since the Kaplan–Meier OS curve significantly differs in relation to preoperative serum VEGF levels [49]. Wang et al. corroborated these findings by stratifying patients according to type A vs. type C VEGF [50]. A synergic action between chemotherapy and angiogenesis inhibition is plausible due to the experimental model’s results showing that bevacizumab improves the penetration of paclitaxel and the antitumor effect on a MX-1 breast cancer xenograft [51]. Moreover, VEGF and HIF-1alpha are dose-dependently decreased by SN-38 in experimental models [52]. These results prompted an intensive investigation in order to better sketch the proper patient for the proper treatment. However, the adaptive–evasive responses by tumors to anti-angiogenic therapies represent an unmet need [40], due to the lack of validated soluble biomarkers, despite the intensive investigation also in the field of liquid biopsy [53][54]. A paradigm shift has been opened by the discovery of the glycosylation-dependent galectin-VEGFR-2 binding, which preserves angiogenesis in anti-VEGF refractory tumors [55]. This study initiated an intense investigation regarding efforts aiming to overcome resistance to angiogenesis inhibitors.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13143433

References

- Marmé, D. Tumor Angiogenesis A Key Target for Cancer Therapy; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-3-319-31215-6.

- Hurwitz, H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Novotny, W.; Cartwright, T.; Hainsworth, J.; Heim, W.; Berlin, J.; Baron, A.; Griffing, S.; Holmgren, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus Irinotecan, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2335–2342.

- Hartmann, J.T.; Haap, M.; Kopp, H.-G.; Lipp, H.-P. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors—A Review on Pharmacology, Metabolism and Side Effects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009, 10, 470–481.

- Gaya, A.; Tse, V. A Preclinical and Clinical Review of Aflibercept for the Management of Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2012, 38, 484–493.

- Van der Veldt, A.A.M.; Lubberink, M.; Bahce, I.; Walraven, M.; de Boer, M.P.; Greuter, H.N.J.M.; Hendrikse, N.H.; Eriksson, J.; Windhorst, A.D.; Postmus, P.E.; et al. Rapid Decrease in Delivery of Chemotherapy to Tumors after Anti-VEGF Therapy: Implications for Scheduling of Anti-Angiogenic Drugs. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 82–91.

- Mancuso, M.R.; Davis, R.; Norberg, S.M.; O’Brien, S.; Sennino, B.; Nakahara, T.; Yao, V.J.; Inai, T.; Brooks, P.; Freimark, B.; et al. Rapid Vascular Regrowth in Tumors after Reversal of VEGF Inhibition. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2610–2621.

- Grothey, A.; Sugrue, M.M.; Purdie, D.M.; Dong, W.; Sargent, D.; Hedrick, E.; Kozloff, M. Bevacizumab beyond First Progression Is Associated with Prolonged Overall Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Results from a Large Observational Cohort Study (BRiTE). J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 5326–5334.

- Argentiero, A.; Solimando, A.G.; Brunetti, O.; Calabrese, A.; Pantano, F.; Iuliani, M.; Santini, D.; Silvestris, N.; Vacca, A. Skeletal Metastases of Unknown Primary: Biological Landscape and Clinical Overview. Cancers 2019, 11, 1270.

- Antonio, G.; Oronzo, B.; Vito, L.; Angela, C.; Antonel-La, A.; Roberto, C.; Giovanni, S.A.; Antonella, L. Immune System and Bone Microenvironment: Rationale for Targeted Cancer Therapies. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 480.

- Kaplan, R.N.; Riba, R.D.; Zacharoulis, S.; Bramley, A.H.; Vincent, L.; Costa, C.; MacDonald, D.D.; Jin, D.K.; Shido, K.; Kerns, S.A.; et al. VEGFR1-Positive Haematopoietic Bone Marrow Progenitors Initiate the Pre-Metastatic Niche. Nature 2005, 438, 820–827.

- Argentiero, A.; Solimando, A.G.; Krebs, M.; Leone, P.; Susca, N.; Brunetti, O.; Racanelli, V.; Vacca, A.; Silvestris, N. Anti-Angiogenesis and Immunotherapy: Novel Paradigms to Envision Tailored Approaches in Renal Cell-Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1594.

- Shen, C.; Kaelin, W.G. The VHL/HIF Axis in Clear Cell Renal Carcinoma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013, 23, 18–25.

- Goldman, C.K.; Kim, J.; Wong, W.L.; King, V.; Brock, T.; Gillespie, G.Y. Epidermal Growth Factor Stimulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Production by Human Malignant Glioma Cells: A Model of Glioblastoma Multiforme Pathophysiology. Mol. Biol. Cell 1993, 4, 121–133.

- Jain, R.K. Normalizing Tumor Microenvironment to Treat Cancer: Bench to Bedside to Biomarkers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2205–2218.

- Wilson, W.R.; Hay, M.P. Targeting Hypoxia in Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 393–410.

- Lu, K.V.; Chang, J.P.; Parachoniak, C.A.; Pandika, M.M.; Aghi, M.K.; Meyronet, D.; Isachenko, N.; Fouse, S.D.; Phillips, J.J.; Cheresh, D.A.; et al. VEGF Inhibits Tumor Cell Invasion and Mesenchymal Transition through a MET/VEGFR2 Complex. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 21–35.

- Finger, E.C.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxia, Inflammation, and the Tumor Microenvironment in Metastatic Disease. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010, 29, 285–293.

- Semenza, G.L. Oxygen Sensing, Hypoxia-Inducible Factors, and Disease Pathophysiology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2014, 9, 47–71.

- Solimando, A.G.; Summa, S.D.; Vacca, A.; Ribatti, D. Cancer-Associated Angiogenesis: The Endothelial Cell as a Checkpoint for Immunological Patrolling. Cancers 2020, 12, 3380.

- Sounni, N.E.; Cimino, J.; Blacher, S.; Primac, I.; Truong, A.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Paye, A.; Calligaris, D.; Debois, D.; De Tullio, P.; et al. Blocking Lipid Synthesis Overcomes Tumor Regrowth and Metastasis after Antiangiogenic Therapy Withdrawal. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 280–294.

- Vandyke, K.; Zeissig, M.N.; Hewett, D.R.; Martin, S.K.; Mrozik, K.M.; Cheong, C.M.; Diamond, P.; To, L.B.; Gronthos, S.; Peet, D.J.; et al. HIF-2α Promotes Dissemination of Plasma Cells in Multiple Myeloma by Regulating CXCL12/CXCR4 and CCR1. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 5452–5463.

- Solimando, A.G.; Vacca, A.; Ribatti, D. A Comprehensive Biological and Clinical Perspective Can Drive a Patient-Tailored Approach to Multiple Myeloma: Bridging the Gaps between the Plasma Cell and the Neoplastic Niche. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 6820241.

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxic Control of Metastasis. Science 2016, 352, 175–180.

- Shojaei, F.; Wu, X.; Zhong, C.; Yu, L.; Liang, X.-H.; Yao, J.; Blanchard, D.; Bais, C.; Peale, F.V.; van Bruggen, N.; et al. Bv8 Regulates Myeloid-Cell-Dependent Tumour Angiogenesis. Nature 2007, 450, 825–831.

- Ciesielski, O.; Biesiekierska, M.; Panthu, B.; Vialichka, V.; Pirola, L.; Balcerczyk, A. The Epigenetic Profile of Tumor Endothelial Cells. Effects of Combined Therapy with Antiangiogenic and Epigenetic Drugs on Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2606.

- Luo, M.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Shao, S.; Huang, S.; Meng, D.; Liu, L.; Feng, L.; Xia, P.; Qin, T.; et al. VEGF/NRP-1axis Promotes Progression of Breast Cancer via Enhancement of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Activation of NF-ΚB and β-Catenin. Cancer Lett. 2016, 373, 1–11.

- Shimizu, T.; Ishida, J.; Kurozumi, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Otani, Y.; Oka, T.; Tomita, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Uneda, A.; Matsumoto, Y.; et al. δ-Catenin Promotes Bevacizumab-Induced Glioma Invasion. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 812–822.

- Jahangiri, A.; De Lay, M.; Miller, L.M.; Carbonell, W.S.; Hu, Y.-L.; Lu, K.; Tom, M.W.; Paquette, J.; Tokuyasu, T.A.; Tsao, S.; et al. Gene Expression Profile Identifies Tyrosine Kinase C-Met as a Targetable Mediator of Antiangiogenic Therapy Resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 1773–1783.

- Finley, S.D.; Chu, L.-H.; Popel, A.S. Computational Systems Biology Approaches to Anti-Angiogenic Cancer Therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 187–197.

- Costa, M.; Danesi, R.; Agen, C.; Di Paolo, A.; Basolo, F.; Del Bianchi, S.; Del Tacca, M. MCF-10A Cells Infected with the Int-2 Oncogene Induce Angiogenesis in the Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane and in the Rat Mesentery. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 9–11.

- Ferrara, N.; Carver-Moore, K.; Chen, H.; Dowd, M.; Lu, L.; O’Shea, K.S.; Powell-Braxton, L.; Hillan, K.J.; Moore, M.W. Heterozygous Embryonic Lethality Induced by Targeted Inactivation of the VEGF Gene. Nature 1996, 380, 439–442.

- Roy, H.; Bhardwaj, S.; Ylä-Herttuala, S. Biology of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 2879–2887.

- Verdegem, D.; Moens, S.; Stapor, P.; Carmeliet, P. Endothelial Cell Metabolism: Parallels and Divergences with Cancer Cell Metabolism. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2, 19.

- Aird, W.C. Endothelial Cell Heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006429.

- Krebs, M.; Solimando, A.G.; Kalogirou, C.; Marquardt, A.; Frank, T.; Sokolakis, I.; Hatzichristodoulou, G.; Kneitz, S.; Bargou, R.; Kübler, H.; et al. MiR-221-3p Regulates VEGFR2 Expression in High-Risk Prostate Cancer and Represents an Escape Mechanism from Sunitinib In Vitro. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 670.

- Cai, W.; Chen, X. Multimodality Molecular Imaging of Tumor Angiogenesis. J. Nucl. Med. 2008, 49, 113S–128S.

- Chouaib, S.; Messai, Y.; Couve, S.; Escudier, B.; Hasmim, M.; Noman, M.Z. Hypoxia Promotes Tumor Growth in Linking Angiogenesis to Immune Escape. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 21.

- Yamashita-Kashima, Y.; Fujimoto-Ouchi, K.; Yorozu, K.; Kurasawa, M.; Yanagisawa, M.; Yasuno, H.; Mori, K. Biomarkers for Antitumor Activity of Bevacizumab in Gastric Cancer Models. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 37.

- Sun, X.-T.; Yuan, X.-W.; Zhu, H.-T.; Deng, Z.-M.; Yu, D.-C.; Zhou, X.; Ding, Y.-T. Endothelial Precursor Cells Promote Angiogenesis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 4925–4933.

- Backer, M.V.; Backer, J.M. Imaging Key Biomarkers of Tumor Angiogenesis. Theranostics 2012, 2, 502–515.

- Laking, G.R.; West, C.; Buckley, D.L.; Matthews, J.; Price, P.M. Imaging Vascular Physiology to Monitor Cancer Treatment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2006, 58, 95–113.

- Goel, S.; Duda, D.G.; Xu, L.; Munn, L.L.; Boucher, Y.; Fukumura, D.; Jain, R.K. Normalization of the Vasculature for Treatment of Cancer and Other Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 1071–1121.

- Linehan, W.M.; Vasselli, J.; Srinivasan, R.; Walther, M.M.; Merino, M.; Choyke, P.; Vocke, C.; Schmidt, L.; Isaacs, J.S.; Glenn, G.; et al. Genetic Basis of Cancer of the Kidney: Disease-Specific Approaches to Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 6282S–6289S.

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jin, H.; Sun, L.; Dong, H.; Xu, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; et al. HIF-1α and HIF-2α Correlate with Migration and Invasion in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 10, 376–382.

- Tanigawa, N.; Amaya, H.; Matsumura, M.; Shimomatsuya, T. Correlation between Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Tumor Vascularity, and Patient Outcome in Human Gastric Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997, 15, 826–832.

- Youssoufian, H.; Hicklin, D.J.; Rowinsky, E.K. Review: Monoclonal Antibodies to the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 in Cancer Therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 5544s–5548s.

- Maeda, K.; Chung, Y.S.; Ogawa, Y.; Takatsuka, S.; Kang, S.M.; Ogawa, M.; Sawada, T.; Sowa, M. Prognostic Value of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Expression in Gastric Carcinoma. Cancer 1996, 77, 858–863.

- Suzuki, S.; Dobashi, Y.; Hatakeyama, Y.; Tajiri, R.; Fujimura, T.; Heldin, C.H.; Ooi, A. Clinicopathological Significance of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF)-B and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A Expression, PDGF Receptor-β Phosphorylation, and Microvessel Density in Gastric Cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 659.

- Villarejo-Campos, P.; Padilla-Valverde, D.; Martin, R.M.; Menéndez-Sánchez, P.; Cubo-Cintas, T.; Bondia-Navarro, J.A.; Fernández, J.M. Serum VEGF and VEGF-C Values before Surgery and after Postoperative Treatment in Gastric Cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 15, 265–270.

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Fang, J.; Yang, C. Overexpression of Both VEGF-A and VEGF-C in Gastric Cancer Correlates with Prognosis, and Silencing of Both Is Effective to Inhibit Cancer Growth. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2013, 6, 586–597.

- Yanagisawa, M.; Yorozu, K.; Kurasawa, M.; Nakano, K.; Furugaki, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Mori, K.; Fujimoto-Ouchi, K. Bevacizumab Improves the Delivery and Efficacy of Paclitaxel. Anticancer Drugs 2010, 21, 687–694.

- Kamiyama, H.; Takano, S.; Tsuboi, K.; Matsumura, A. Anti-Angiogenic Effects of SN38 (Active Metabolite of Irinotecan): Inhibition of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Alpha (HIF-1alpha)/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Expression of Glioma and Growth of Endothelial Cells. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 131, 205–213.

- Giuliano, S.; Pagès, G. Mechanisms of Resistance to Anti-Angiogenesis Therapies. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1110–1119.

- Russano, M.; Napolitano, A.; Ribelli, G.; Iuliani, M.; Simonetti, S.; Citarella, F.; Pantano, F.; Dell’Aquila, E.; Anesi, C.; Silvestris, N.; et al. Liquid Biopsy and Tumor Heterogeneity in Metastatic Solid Tumors: The Potentiality of Blood Samples. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 95.

- Croci, D.O.; Cerliani, J.P.; Dalotto-Moreno, T.; Méndez-Huergo, S.P.; Mascanfroni, I.D.; Dergan-Dylon, S.; Toscano, M.A.; Caramelo, J.J.; García-Vallejo, J.J.; Ouyang, J.; et al. Glycosylation-Dependent Lectin-Receptor Interactions Preserve Angiogenesis in Anti-VEGF Refractory Tumors. Cell 2014, 156, 744–758.