The Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization of METI is different from the general survey of cultural relics, based more on the industrial significance in the process of modernization of Japan, focusing on the economic value and development function of heritage, and facilitating the cooperation and promotion between local governments and industries [

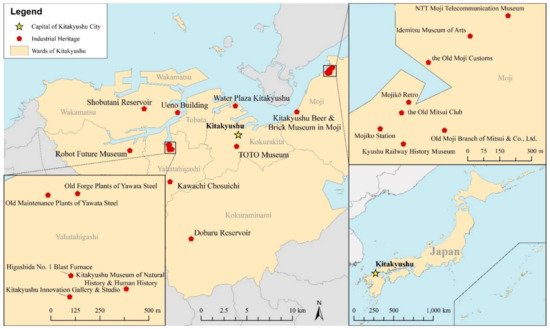

64]. Under the guidance of national policy, industrial heritage was increasingly regarded by traditional industrial cities as an important resource to rejuvenate the local economy [

65]. In other words, industrial heritage was commercialized for touristic activities, since it was expected not only to meet the new needs of tourists (e.g., night sightseeing, leisure, and cultural creativity, but also to transform industrial structure and increase employment.

3. Industrial Heritage Tourism Development in Early Years

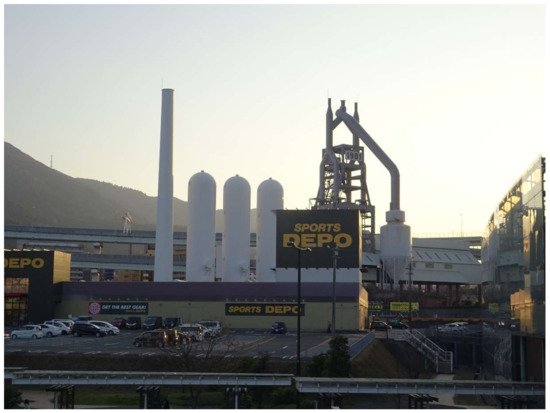

As we mentioned above, because of both the global and national postindustrial transformation and local pollution, since the 1970s, many industrial facilities in Kitakyushu City were forced to be relocated, and some former industrial spaces were transformed for recreational and touristic activities. The most famous was the Yawata Steelworks of Nippon Steel Corporation, which was often regarded as an important symbol of Japan’s modernization. One of its landmark buildings, Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace, stopped operation in 1972 due to the steel industry restructuring (Figure 2). The following year, after environmental improvement (planting cherry and other trees around it), this place was transformed from a traditional industrial landscape into a space for leisure and relaxation (a memorial square open to the public).

Figure 2. Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace, photography: Toshiyuki Morishima.

In 1989, the Nippon Steel Corporation planned to use its idle space after the relocation of the factory for commerce and tourism development, where commercial residences, theme parks, luxury hotels, etc. were set up. Its landmark building, Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace was supposed to be demolished. However, this led to a protection movement spontaneously organized and volunteered by local residents, many of whom were former employees of the Yawata Steel Works. With active lobbying from all walks of life, the government of the Yawata District and the municipal government of Kitakyushu finally identified the Blast Furnace as a National Historic Site in 1996, thus preserving it. The project has thus become a model for local residents in Japan to promote the protection of industrial heritage from the bottom to the top. After the renovation, the Blast Furnace was opened to ordinary tourists before the Kitakyushu Expo Festival in 2001. Concomitantly, the refining furnace and special train for transporting coal and iron ore near it were also preserved and exhibited. With the increase in the number of tourists, the Nippon Steel Corporation opened up a unique viewing site, equipped it with detailed signs and guides, and arranged its employees to make oral explanations when there were a large number of tourists. A few of them commented:

For us, it is not so much to develop tourism as to preserve better and display the history of our enterprise, so we do not care about tourism revenue.

Many local citizens are so active that they volunteer to help make oral explanations on weekends. We applaud this very much.

All these early tourism facilities of industrial heritage were directly undertaken and managed by the Nippon Steel Corporation. As the development of industrial heritage tourism is an integral part of corporate social responsibility and enhances the corporate image and reputation, the Nippon Steel Corporation chose to open the site to the public free of charge. In fact, although Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace is used for preservation and exhibition, most buildings of the Yawata Steel Works are still in use and operation today, including the earliest First Head Office building, which was completed in 1899, and the earliest steel structure building in the Japan Maintenance Plants, which has been in operation for more than 110 years. Old Forge Plants, which is now used as the corporate archive center, has not yet been opened to the general public. Therefore, a series of enterprise-led planning and construction of industrial heritage exhibition spaces can only be regarded as the extension of the established path.

Likewise, Mojiko, another important industrial heritage site of Kitakyushu, was founded in 1889 and initially developed as a vital coal transportation port, which gradually became an important commercial port and an important center of railways, logistics, finance, and trade in modern Japan. However, in the second half of the 20th century, with the decline of heavy industry and the launch of the Kanmon Tunnel, the port declined gradually in terms of both freight and passenger transport. Concurrently, the previous finance and trade enterprises, and other commercial businesses out-migrated in succession, and many modern industrial factories and commercial buildings were left vacant. The Mojiko Station in Moji Ward is the only station building as an industrial heritage in Kitakyushu City, which was designated as one of two named as an Important National Cultural Property of Japan (the other is Tokyo Station). The Mojiko Station was built in 1914 in the Renaissance style, modeled on the Termini Station in Italy, and is still in operation. Another essential industrial heritage is Kitakyushu Beer & Brick Museum in Moji. This museum was transformed from the main building of the Kyushu factory in 2005. This factory was established in 1913 by Sapporo Beer, but was relocated in 2000. Since then, it has been idled before it was redeveloped as a museum.

Other former industrial spaces were successively transformed into cultural and commercial facilities. For example, the Kyushu Railway History Museum located near Mojiko Station was the previous headquarter of the Kyushu Railway Company established in 1891. After renovation, the museum was officially opened to the public in 2003, which was mainly used to display the storied history of Kyushu’s railway system. To enhance the tourists’ experience function, the historical museum introduced a simulated driving cab and amusement space for children.

Similarly, the NTT Moji Telecommunication Museum was transformed from the Moji Post and Telecommunications Office which was built in 1924. After its relocation, NTT developed the space into a telecommunication-themed museum and opened it to the public free of charge. The museum exhibits a variety of historical materials on the telegraph and on the telephones that were used in the past in Japan. Many historical museums were established by private enterprises. The phenomenon is attributed partly to the industrial heritage-related preferential policies from the central government of Japan, as a senior staff of the NTT Moji Telecommunication Museum pointed out when he was interviewed:

The Japanese government has implemented tax relief measures for private enterprises to set up museums. The Agency for Cultural Affairs also encouraged support projects for creative activities of museums cooperating with local governments. Thus, enterprises have much enthusiasm to apply for a certain amount of funds.

4. Heritage Transformation Drivn by Regional Policies

While local enterprises spontaneously launched the protection of industrial heritage and the construction of museums, Kitakyushu’s municipal government formulated a series of development plans. In 1988, the municipal government officially proposed the Renaissance Plan, which repositioned the development direction of Kitakyushu City in the 21st century as “a green industrial city centered on industries of science and technology, environmental protection and tourism by promoting the transformation of old industrial areas.” In 1991, in order to promote the revitalization of local culture, the municipal government established the Cultural Promotion Fund to support various art and cultural activities launched and organized by local residents spontaneously.

For more than 20 years, the Kitakyushu City has made remarkable achievements in environmental improvement and scientific and technological innovation. It was awarded the first “Eco-City”, and “Green Asia International Strategic Comprehensive Special Zone” by the central government of Japan, and “one of four Green Growth Model Cities” by OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). In April 2007, the Kitakyushu Innovation Gallery & Studio (KIGS) was opened in the original site of the Yawata Steelworks. It stimulated the emergence of a cluster of cultural sites, for instance, the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History & Human History, the Kitakyushu Environment Museum, and the Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace.

In recent years, inspired by the theory of Creative Cities, the municipal government further formulated the Cultural Promotion Plan in 2010 to build Kitakyushu as a “city with rich education and culture”, and special funds were created to support the establishment of local art galleries and museums. Under the government supports, some industrial heritage buildings were transformed into the places for the inheritance of traditional skills to cultivate future artists and folk craftsmen. Furthermore, the municipal government of Kitakyushu created a number of spectacular factory night views as the Kitakyushu cityscape view at night. The nighttime views include the complete-set cluster of equipment of the past chemical factories, ironmaking plants, and huge chimneys. Thus, Kitakyushu City has become one of the three most beautiful cities at night in Japan.

A group of abandoned traditional industrial buildings was registered in the 2000s as national cultural assets, such as the Ueno Building, the Old Moji Customs, and the Kawachi Chosuichi (Figure 3). The municipal government reached an agreement of property rights transfer with some of their original owners and spent money rebuilding them for public cultural spaces. For example, the Old Moji Branch of Mitsui & Co., Ltd. the highest office building in Kyushu in the Taisho period (1912–1926), has been owned by the Kyushu Railway Company since World War II. In 2005, its ownership was transferred to Kitakyushu City. Later, the municipal government made a series of reconstructions to make it an important cultural space with a concert hall, an art gallery, a historical data room, and a maritime information center. An additional example is the Idemitsu Museum of Arts. It was the former site of the material warehouse built by the petroleum company Idemitsu Kosan in the early 20th century and was opened to the public in 2000, displaying a large number of calligraphy and painting works and ceramic ware.

Figure 3. Mojiko Retro in Kitakyushu, photography: Zhengyuan Zhao.

However, to reduce the burden of local finance, the municipal government of Kitakyushu has consciously transformed some spaces into commercial spaces such as cafes, restaurants, and wedding venues. For example, the Old Moji Customs in the Moji ward, was opened to the public in 1995. In addition to the exhibition space for introducing customs history, commercial facilities, such as a retro cafe, art gallery, and prospect room, were given for lease. The Old Mitsui Club was built by Mitsui Co., Ltd. in 1921 as a reception center to provide accommodation for VIPs. Albert Einstein stayed here during his visit to Japan with his wife in 1922. On the second floor of the Old Mitsui Club, the “Einstein Memory Showcase” is displayed together with the life and creation of Fumiko Hayashi, a Japanese writer born in Moji, while the first floor of the Old Mitsui Club has been transformed into a restaurant.

With the recognition of the Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization since 2007, the industrial heritage has been regarded by local governments in Kitakyushu City as an important tourism resource. With their efforts, many industrial heritage sites have been included in different categories. First, the Yawata Steelworks and the Old Moji Customs were selected into “33 Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization” as heritage constellations of the modern steel industry and heritage constellations of the coal industry in Kyushu and Yamaguchi, respectively. Later, more industrial heritage sites, modern buildings, public facilities, and museums distributed in various parts of the city were selected into “33 Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization Vol. 2” in 2009 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Heritage Constellations of Industrial Modernization in Kitakyushu City.

| Major Heritage in Kitakyushu |

Heritage Constellations |

| Higashida No. 1 Blast Furnace; Yawata Steel Works et al. |

Heritage constellations of modern steel industry |

| Old Moji Customs; Old Mitsui Club et al. |

Heritage constellations of coal industry in Kyushu and Yamaguchi |

| JR Mojiko Station |

Heritage constellations of train ferry |

| Dobaru Reservoir: Shobutani Reservoir |

Heritage constellations of modern water supply |

| NTT Moji Telecommunication Museum |

Heritage constellations of modern telecommunications |

| Buildings in Kyushu Institute of Technology |

Heritage constellations of engineering education |

| Kitakyushu Beer & Brick Museum in Moji; TOTO Museum et al. |

Heritage constellations of ceramic industry in North Kyushu |

The municipal government of Kitakyushu began to actively cooperate with the central government and surrounding areas in the later 2000s to boost the declaration of world heritage. After the Kyushu and Yamaguchi Modern Industrial Heritage Group was included in the Tentative List of World Heritage in January 2009, as Japan’s first serial nomination project, it received generous support from the central and local governments. The central government took the lead role in promoting cross-regional cooperation to initiate and direct the World Heritage nomination process. Finally, in 2015, the First Head Office Building, the Maintenance Plants, the Old Forge Plants, and other modern buildings of Yawata Steelworks were included in The World Cultural Heritage List as part of the Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution.

5. The Formation of Industrial Tourism and Its Expansion

Although the industrial heritage tourism in Kitakyushu emerged at the end of the 20th century, driven by local manufacturing enterprises, it entered a stage of rapid development after 2010. In 2010, the Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Kitakyushu City officially declared industrial heritage as a strategic tourism resource to revitalize the region. In 2014, the municipal government of Kitakyushu, Kitakyushu Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and Kitakyushu Tourism Association jointly established the Kitakyushu Industrial Tourism Center (KITC) and launched a one-stop industrial tourism window service. The KITC works with travel agencies to develop tourist routes, and hires approximately 80 local citizens as tour guides.

With the expansion of the industrial heritage tourism, in recent years tourists have not only visited factory buildings and facilities, but also showed a strong interest in visiting the living areas of workers in the past industrial era. Thus, the KITC has completed the planning of teaching materials and projects in cooperation with local primary and secondary schools. Some individuals remarked:

I worked here before retirement. I would like to introduce my own past life experiences to arouse the common feeling of our generation. Many students from local and surrounding primary and secondary schools come here for school trips, and teachers lead them to conduct various surveys and interviews.

The vigorous development of industrial heritage tourism has also directly driven the development of science and technology tourism, environmental tourism, and other types of industrial tourism. A head of KITC commented:

Traditionally, the impression of Kitakyushu by ordinary Japanese was mainly focused on Kanmon Straits and Mojikō. However, in recent years, we have developed new projects in cooperation with well-known enterprises centered on industrial heritage and high technology, and actively explored the MICE market, which has tremendously changed the destination image of the entire city.

As the KITC summarized, the sources of industrial tourism in Kitakyushu consists of industrial heritage, factory tour, and factory night view. By combining industrial heritage with modern cityscape and high-tech experience sightseeing, Kitakyushu has become a major industrial tourism destination of Japan. First, as a model of successful transformation among Japan’s heavy industrial cities, the municipal government of Kitakyushu created several research and study tourism projects for environmental protection, for instance, the visits of the Water Plaza Kitakyushu (an integrated seawater desalination and sewage reuse system applying cutting-edge technologies) and other environmental protection and recycling technology facilities.

Second, the municipal government developed industrial tourism projects with advanced technology in cooperation with local enterprises. Under the generous government support, for instance, Zenrin (a mapping and navigation software enterprise), TOTO (a sanitary ceramics manufacturer), and Yaskawa Electric (a leading global manufacturer of industrial robots) have been active in developing industrial tourism. Yaskawa Electric established the Robot Future Museum, and TOTO set up the Enterprise Information Museum in 2015.

Third, KITC worked with tourism agencies to integrate various former industrial facilities and the night views into tourist routes. To satisfy the increasing demand of night sightseeing tourists, the municipal government and travel companies have cooperated to officially launch a new project of factory zone night view suitable for office workers since 2011, so that tourists can enjoy the night view in various parts of the city by bus and cruise ships. Moreover, in Mojikō Retro, the “Romantic Lantern Festival in the Nostalgic Area of Moji” has been launched in winter since 2013. The historical buildings and trees around the Mojikō Retro are illuminated to create a romantic atmosphere. In addition, KITC has helped develop and promote new tourist souvenirs for local unique products. As a result, the number of industrial sightseeing tourists increased from 428,000 in 2014 to nearly 700,000 in 2019. A senior staff at KITC pointed out in our interview:

We will also invite film and television crews and cartoonists to find views from the old landscape preserved by industrial heritage. These works can not only contribute to the spread of Kitakyushu industrial heritage at home and abroad, but also attract fans and tourists who pursue a pilgrimage to a holy land.