Cardiovascular diseases are the most common causes of hospitalization, death and disability in Europe. Despite our knowledge of nonmodifiable and modifiable cardiovascular classical risk factors, the morbidity and mortality in this group of diseases remains high, leading to high social and economic costs. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new factors, such as the gut microbiome, that may play a role in many crucial pathological processes related to cardiovascular diseases. Diet is a potentially modifiable cardiovascular risk factor. Fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and minerals are nutrients that are essential to the proper function of the human body.

- gut microbiome

- diet

- heart

- cardiovascular risk factors

- cardiovascular diseases

1. Introduction

2. Diet pattern

2.1. Traditional vs. Modern Industrialized Diet

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

3. Diet Compound

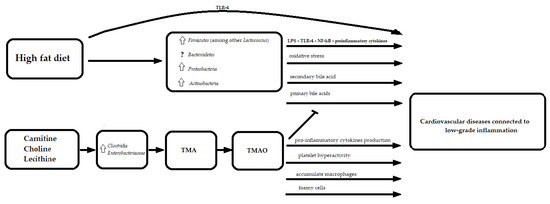

3.1. Fats

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

| Pattern of the Diet | Increase in Microbiome | Decrease in Microbiome |

|---|---|---|

| High fat diet |

|

|

| High protein plant diet |

|

|

| High protein animal diet |

|

|

| Dietary protein amount: 100 to 200 g/kg |

|

|

| Dietary protein amount: dose greater than 200 g/kg |

|

|

| High carbohydrates diet |

|

|

| High fiber diet |

|

|

| Diet sufficient with vitamin D |

|

|

| Diet sufficient with vitamin A |

|

|

| Diet sufficient with vitamin B12 |

|

|

| Diet sufficient with vitamin E |

|

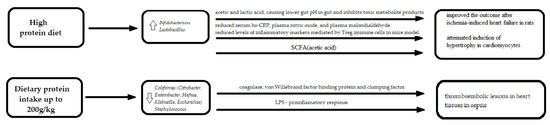

3.2. Proteins

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

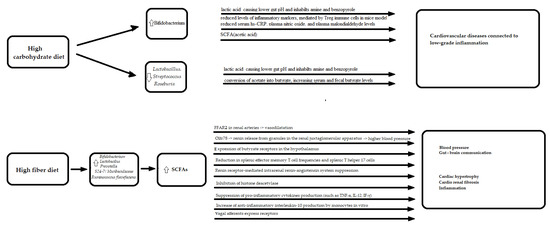

3.3. Carbohydrates

3.3.1. Dietary Fiber

3.3.2. What Does It Mean for the Heart?

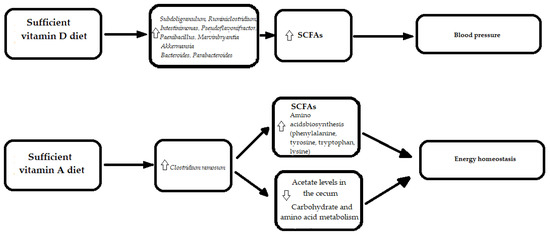

3.4. Vitamins

What Does It Mean for the Heart?

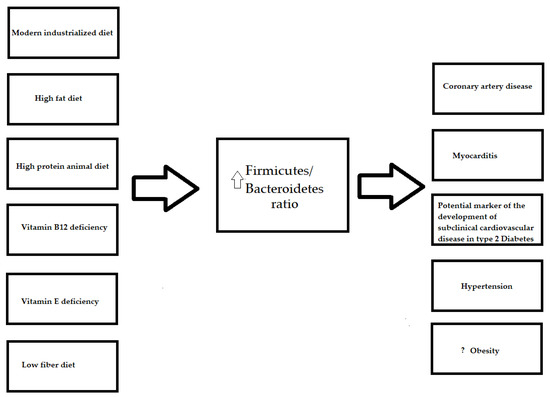

3.5. Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio and Diet

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13114146