Tendon and ligament injury poses an increasingly large burden to society. With surgical repair and grafting susceptible to high failure rates, tissue engineering provides novel avenues for treatment.

- mesenchymal stem cells

- extracellular vesicles

- tendon

- ligament

- biomechanics

- macrophage

1. Introduction

Tendon and ligament injuries make up about 50% of all musculoskeletal injuries and cost $30 billion a year to manage [1]. These can be due to underlying tendon diseases, such as inflammatory or degenerative changes seen in tendinopathies, or due to acute traumatic injury. Tendons generally have limited vascularisation when compared to muscle, especially at the tendon–bone interface. There is reduced angiogenesis at these sites due to inhibitory factors such as endostatin, secreted from neighbouring cells [2]. The blood supply to tendons generally comes from three sources: the myotendinous junction, the osteotendinous junction, and the tendon sheath. Ligaments, on the other hand, have blood supply from the synovium as well as from the surrounding soft tissue. The healing response in ligaments can be divided into the hemorrhagic, inflammatory, reparative, and remodelling phases. The final phase can take up to months or years to complete, and is subject to a number of external factors, with minimal exercise, smoking, and high cholesterol associated with poorer outcomes [3]. These injuries can be severely debilitating, whether in athletes trying to return to their high level of sporting ability, or patients returning to independent living. Furthermore, a suboptimal healing process can cause scar tissue formation, increasing the chance of reinjury [4].

Traditional methods of tendon and ligament repair include suture anchors [5][6] and autogenous tendon grafts [7]. When tendons are divided, the ends can be approximated and sutured to promote healing. Complications such as adhesions [8], repair site gap formation [9], or chondrolysis [10] may occur. Tissue grafting is another well-established method of tendon repair. Autograft involves harvesting tissue from the patient’s own body to replace the damaged tissue, and despite the success rate, complications such as donor site morbidity issues or lack of adequate tissue may arise. Allograft and xenograft involve tissue transplantation from a human or animal, respectively. These have greater availability and flexibility but risk rejection, disease transmission, and zoonotic transmission [11].

In recent years, developments of stem cell therapies have created new avenues for treatment [12]. Induced pluripotent (iPSC) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) have the highest differentiation capacity and flexibility; however the unlimited regenerative nature of these cells can potentially increase the risk of teratoma development [13] or ectopic bone formation [14]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) do not have the ethical concerns that surround the use of ESCs but can potentially influence tumorigenesis and lead to cancer treatment resistance [11]. These cells can be used in isolation or with appropriate biomaterial using a suitable scaffolding technique to create the most appropriate environment for tissue regeneration. The purpose of an ideal scaffold should be to seamlessly transition from the artificial alignment of the damaged tissue to the natural regeneration of native tissue using the body’s inherent processes [15].

Recently, there has been a shift in the approach to cell-free therapy, with extracellular components shown to have similar regenerative properties without the potentially harmful effects of entire cell transplantations [16]. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are extracellular lipid membrane–bound particles that contain host cell-derived protein or nucleic acid messengers, and have an effect on target cells via paracrine or autocrine regulatory functions [17]. This new type of therapy has the potential to change the microenvironment of healing tissue, reducing the inflammatory process and promoting regeneration, as shown in various studies across different organ systems, such as neural [18], musculoskeletal [19], and cardiac [20] tissues.

2. Methodology

An initial review of the literature was performed to gauge the heterogeneity of the literature, after which our search criteria were formulated. This lowered the chance that important studies would be missed.

On 26 May 2021, a systematic search was performed on Embase, Medline, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library, which were considered comprehensive. No filters of any sort were used, and databases were searched from conception. The search strategy is shown in Supplementary Table S1 . All studies found were imported into Mendeley and deduplicated. VL and MT independently completed title and abstract screening and agreement between authors was assessed and generated 93% agreement. A third reviewer (WK) was contacted for unresolvable disagreements. Next, full-text screening was performed by VL and MT, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria shown in Supplementary Table S2 . Again, a third reviewer (WK) was consulted for any disagreements. A ‘snowball’ search was then performed on 2 June 2021, whereby references of the included studies as well as studies that cited any of the included studies were independently searched by VL and MT, using Google Scholar to identify and screen studies. Studies that performed in vivo experiments, using EVs isolated from human– or animal–derived MSCs, were included. Studies that characterised their MSC population using guidelines from the International Society for Cellular Therapy [21] and characterised their EV population using International Society for Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) standards were included [22]. In vitro, ex vivo, and in silico studies were excluded, and studies without a control arm were excluded.

Data extraction was independently performed by VL and MT, with a third reviewer (WK) to resolve disagreements. Data were extracted into data tables created in a standardised excel spreadsheet for assessment of study quality and evidence synthesis. Data from each study were split into 4 categories:

- Isolation and characterisation of MSCs, including source of MSCs, cellular origin, cell treatment to extract MSCs, and procedures to verify MSCs (e.g., flow cytometry, western blotting).

- Characterisation and purification of EVs, including MSC purification to extract EVs, EV dimensions, EV biomarkers, imaging used to visualise EVs, and EV active component.

- In vivo model, including method of EV delivery, type of in vivo model, how tendon/ligament injury was induced, animal age, animal weight, animal gender, total number of animals used per experimental group, and follow-up time.

- In vivo findings, including macroscopic appearance, imaging results, histopathological results, biochemical findings, and biomechanical findings.

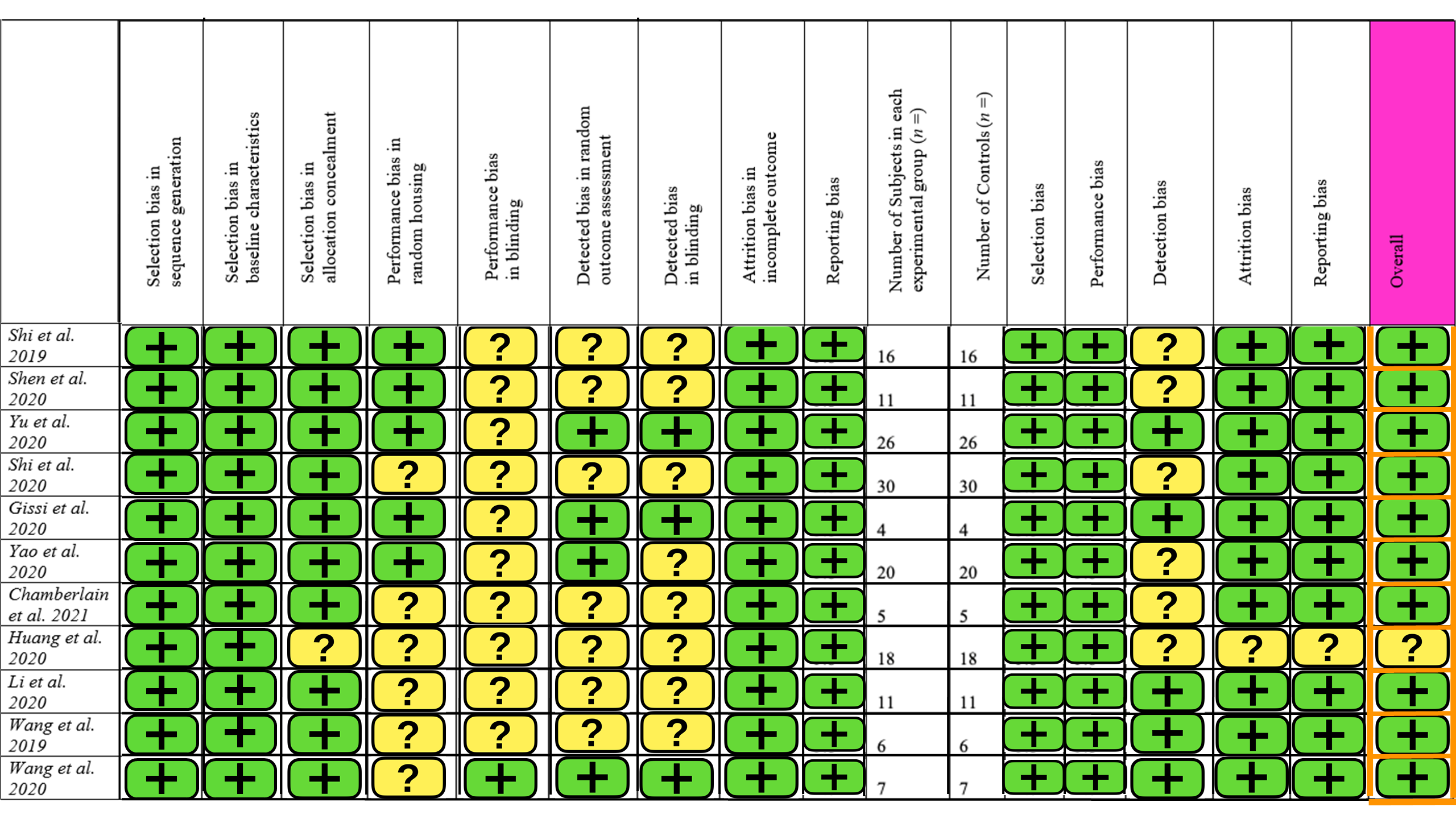

Quality assessment was carried out independently by MT and VL using the SYstematic Review Center for Laboratory animal Experimentation (SYRCLE) tool [23]. The main categories assessed were selection bias, performance bias, blinding bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias. Discrepancies were consulted with WK.

3. Results

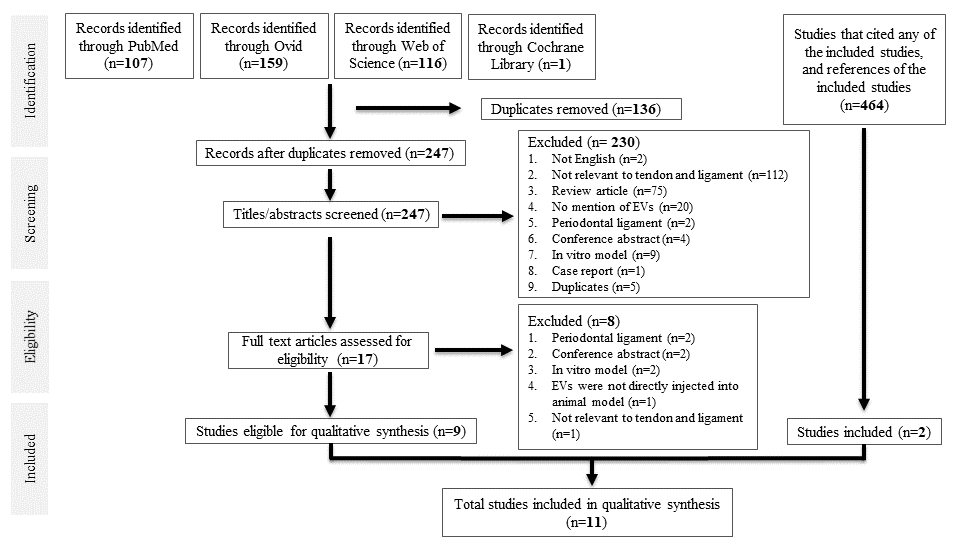

A total of 383 studies were identified from database searching. After de-duplication, 247 studies were identified for title and abstract screening, of which 17 full-text studies were reviewed. Nine studies were eligible for data synthesis. Searching references of the included studies, as well as studies that cited any of the included studies, yielded two more studies, giving a total of 11 studies for qualitative synthesis. All were case–control studies. A PRISMA diagram is shown in Figure 1.

3.1. Characterisation of MSCs

The majority of studies used animal-derived MSCs rather than human-derived MSCs. Of the seven studies that used animal-derived MSCs (involving 310 subjects), the most common MSC donor was Sprague–Dawley rats, with four studies involving 172 subjects utilising them. One study involving 16 subjects used the Lewis rat, and one study involving 32 subjects used NF-_B–luciferase reporter mice [26]. This was done to investigate how MSC-EVs could alter macrophage NF-_B inflammatory signalling. Of the four studies that used human-derived MSCs, involving 138 subjects, two studies involving 93 subjects obtained MSCs from the umbilical cord, one study involving 35 subjects from adipose tissue, and one study involving 10 subjects from bone marrow cells. Regarding the culture medium, alpha-modified minimum essential medium (_-MEM) was most commonly employed, used in seven studies involving 325 subjects. Other culture methods include Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) utilised in two studies involving 72 subjects, MesenCult™ Basal Medium utilised in one study involving 16 subjects [29], and serum-free medium (OriCell) utilised in one study involving 35 subjects.

Regarding the culture medium, alpha-modified minimum essential medium (α-MEM) was most commonly employed, used in seven studies involving 325 subjects. Other culture methods include Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) utilised in two studies involving 72 subjects [24][25], MesenCult™ Basal Medium utilised in one study involving 16 subjects [26], and serum-free medium (OriCell) utilised in one study involving 35 subjects [27].

The two most common methods for characterising MSCs were surface-maker expression using flow cytometry (used in seven studies with 310 subjects [28][29][30][31][26][24][25]), and testing for the absence of haematopoietic surface markers CD34 and CD45 (used in five studies involving 226 subjects [28][31][26][24][25]). Another, less common method was trilineage differentiation into adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes, seen in four studies involving 140 subjects [30][26][24][25].

The most widespread method of visualising EVs was using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (used in nine studies involving 372 subjects [28][29][30][31][32][24][33][25][27]), and of those, three studies involving 105 subjects used the method to also measure EV dimensions [24][33][25]. Other methods of visualising EVs included atomic force microscopy (ATM), used in one study involving 16 subjects [26], and an 80kV electron microscope [34]. Additional methods for visualising EVs include tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS) using Izon’s qNano Gold in four studies involving 125 subjects [28][29][32][27], nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) with ZetaView in three studies involving 202 studies [30][31][34], and AFM in one study [26]. EVs were characterised by flow cytometry and western blotting, with CD9, CD63, TSG-101 being the most common EV markers identified. Gissi et al. attributed the increased extracellular matrix–tendon remodelling to MMP14 and pro-collagen1A2, which were identified in EVs by dot blot [26]. Yao et al. concluded that human umbilical cord-derived MSCs release low levels of miR-21a-3p, which manipulates p65 activity to inhibit tendon adhesion [34].

All studies were designed in a case-control format. Three studies involving 116 subjects divided their experimental subjects into two groups, a control and MSC-EV group [30][32][24]. The rest included multiple experimental groups, with one study involving 35 subjects including a sham surgery group, whereby the tendon would be exposed but not surgically manipulated [27]. One study investigating a dose-dependent relationship between EV concentration and tendon repair further separated their EVs into high (8.4 × 10 12 EVs) and low concentrations (2.8 × 10 12 EVs) [26]. One study utilised hydrogel to promote long-term exosome retention and encourage sustained exosome release, and hence created a separate group that only received hydrogel [31]. Shen et al. compared the efficacy of IFNγ-primed MSC-EVs versus naïve MSC-EVs and hence had three experimental groups in total [29].

3.2 In vivo Findings

Six studies involving 280 subjects performed macroscopic analysis [27,28,30,31,33,35], but one only used it to look for fatty infiltration, confirming the establishment of a rotator cuff tear model (Table 4) [35]. Yu et al. showed that the appearance of the injured tendon better approximated normal tendon after exosome treatment. Two studies involving 100 subjects observed reduced scar formation and two studies involving 93 subjects reported reduced tendon adhesion to peri-tendinous tissue. Histological analysis was performed by all studies. Five studies utilised scoring systems; Shi et al. utilised a fibre alignment score as a proxy for tendon healing. The other four studies involving 161 subjects used histological scores, which includes sub-scores such as fibre structure, cellularity, vascularity, degree of adhesion . Collagen deposition and alignment were assessed by eight studies involving 345 subjects , all of which reported more compact and regularly aligned collagen fibres in EV-treated tendons. One study utilised angiography to show that exosomes promoted angiogenesis around the injury site.

All studies performed biochemical analysis. Four studies involving 227 subjects explicitly mentioned that EVs reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1_ and IL-6, and increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL- 10 and TGF-_1. Shen et al. demonstrated decreased gene expression and protein expression in the tendon not performed. Three studies involving 154 subjects directly tested the impact of EVs on macrophage polarisation . Huang et al. showed that exosomes decreased CD86, anM1 macrophage surface marker, whilst Shi et al. demonstrated that exosomes decreased iNOS+M1 macrophages and increased Arg1+ M2 macrophages, despite the former being done in vitro. However, Chamberlain et al. reported that exosome treatment had no significant effect on M1 or M2 macrophage number, whilst EV-educated macrophages (made by exposing CD14+ macrophages to MSC-EVs) decreased endogenous M1/M2 macrophage ratio. Virtually all studies reported increased expression of genes related to collagen and tendon matrix formation, such as COL1a1, COL2a1, COL3a1, SCX, Sox9. Gissi et al. also reported a more favourable collagen ratio after EV treatment, i.e., increased collagen type I and decreased collagen type III expression [29].

Eight studies performed biomechanical analysis. In a bilateral rotator cuff tear model, Wang et al. found that the mean ultimate load to failure in the MSC-EV treated group was significantly greater (132.7 N versus 96 N) than in the control group. In a murine patellar tendon injury model, Yu et al. noticed that stress at the failure of the regenerated tendons and Young’s modulus were 1.84-fold and 1.86-fold higher in the MSC-EV treated group than controls. Most other studies reported that EV treatment increased the maximum stiffness, breaking load, and tensile strength of regenerated tendons; however, three studies reported no significant difference in biomechanical properties between EVtreated and control groups.

3.3. Risk of Bias

The SYRCLE risk of bias tool for animal studies was used, containing 15 different parameters. A summary of this is provided in Figure 2. Ten studies had a low level of concern overall, but one study had some concern about the risk of bias. The main contributors to bias were blinding and detection bias. There was little selection and reporting bias. Overall, the studies included in this review are of high quality with a low risk of bias.

4. Discussion

Over the past 30 years, MSCs have become a cornerstone of tissue engineering and biotechnology research, having been used in a variety of scenarios, such as evaluating the optimum cell dose for treatment of non-union bone fractures [37] and evaluating the capacity of MSCs for managing osteochondral defects [38]. There has recently been increasing interest in the use of MSCs and their derived EVs for tendon and ligament repair, presenting the need for a review of the current literature in this field.

All studies in this review reported better tendon/ligament repair following treatment with MSC-EVs. A variety of outcome measures were employed in each study to examine the impact of EVs on tendon/ligament repair, but not all studies found improvements in every parameter measured. All 448 subjects were treated with MSC-EVs without immunogenic or significant complications.

4.1. Modifying EVs to Enhance their Biological Function

There are many strategies that can modify bioactive molecules to enhance their treatment effectiveness, such as the active loading of EVs with short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) via electroporation [67] and the genetic modification of human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) to load miR-375 into hASC-derived exosomes to improve osteogenic differentiation [68]. Huang et al. pre-treated MSCs with atorvastatin to increase their cardioprotective function. This resulted in lower cardiomyocyte apoptosis and greater angiogenesis in rat models of acute myocardial infarction [32]. Wang et al. performed cyclic stretch on human periodontal ligament cells resulting in the secretion of exosomes that were better at inhibiting proinflammatory IL-1β secretion from macrophages [34]. Li et al. pre-treated human umbilical MSCs with hydroxycamptothecin, resulting in a greater suppression on fibroblast proliferation and a better extrinsic fibrotic tendon repair, paving the way for improved natural intrinsic tenocyte regeneration [33]. Studies suggest that pro-inflammatory stimuli increase the immunosuppressive functions of MSC-EVs [69,70]. Shen et al. found that IFNγ-primed MSCs produced EVs that can better reduce NF-κB activity and the subsequent expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in injured tenocytes, and promote macrophage differentiation into the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype [26]. A similar effect has also been reported in in vivo models of cartilage injury, with IFNγ-stimulated MSCs enhancing chondrogenesis [71].

4.2. Role of MMP-14 and miR-21 in Tendon/Ligament Repair

The tendon regeneration capabilities of MSC-EVs have been ascribed to various active components that they secrete. Gissi et al. partly attributed the increased tendon healing in a rat Achilles tendon injury model to pro-collagen1A2 and MMP-14 expression in EVs derived from rat bone marrow MSCs (rBMSCs-EVs) [29]. Gulotta et al. suggested that MMP-14, which plays a role in tendon-bone insertion site formation during embryogenesis, is responsible for increased biomechanical strength and fibrocartilage presence at tendon–bone insertion sites [72]. In a complete flexor tendon laceration rat model, Oshiro et al. noted that MMP-14 levels steadily increased in the intermediate to later stages of tendon healing [73]. This suggests that in addition to its key role during embryogenesis [74], MMP-14 is necessary for the remodelling phase of tendon healing. The exact mechanism is unknown; however, some studies suggest that MMP-14 is a key player in the cell surface activation of MMP-2 [75], MMP-9, and MMP-13 [73], resulting in tissue remodelling. Mechanistically, tendon repair via MSC-derived MMP-14 could happen by increased degradation of weaker fibrotic tissue, as suggested by increased cardiac fibroblast degradation after MSC treatment in a rat model of post-ischaemic heart failure [76]. Furthermore, studies have shown that MMP-14 is a collagenolytic enzyme that plays a crucial role in collagen homeostasis, whose inhibition in a mice MMP-14 knockout model led to a fibrosis-like phenotype [77]. MMP-14 could also trigger COX-2 expression, as shown in a study using U87 glioma cells [78]. COX-2 inhibition has been shown to be detrimental to healing at the tendon-to-bone interface in a study where the tendon healing failure rate was significantly higher in rats treated by NSAIDs than in the control group [79]. Thus, it is possible that MMP-14 re-establishes a niche that is similar to native tissue, and conducive to tendon healing.

The beneficial effects of MSC-EVs have also been ascribed to the decreased secretion of mediators. miR-21 is a known regulator of tissue fibrosis. A recent study used high-throughput miRNA sequencing to show that miR-21a-5p was highly enriched in macrophage exosomes and promoted tendon adhesion via Smad7 expression [80]. With this theoretical basis, Yao et al. sequenced human umbilical MSCs (HUMSCs) and their derived exosomes and found that miR-21a-3p was among the most highly expressed [30]. In vivo studies showed that HUMSCs-derived exosomes had a lower expression of miR-21a-3p than HUMSCs, leading to reduced TGF-β1-induced fibroblast proliferation. Excessive extracellular matrix deposition, as indicated by increased collagen III and α-SMA expression, are pathognomonic for fibrotic disease. The lower expression of miR-21a-3p in HUMSCs-derived exosomes resulted in significantly lower collagen III and α-SMA expression, consistent with the conclusion that a low abundance of miR-21 activity leads to decreased fibrosis and tendon adhesion [30].

4.3. EV Educated Macrophages

There is evidence that a main path by which MSC-EVs contribute to tendon and ligament repair is through effects on other cells, with macrophages being important targets. These macrophages are known as EV-educated macrophages (EEVs). It is well known that macrophages play a key role in all stages of tissue repair. Regarding tendon healing, biomechanical testing demonstrated that macrophage metalloelastase-deficient mice had a lower ultimate force and stiffness and a decreased level of type I pro-collagen mRNA compared to wild-type mice [81]. In vivo macrophage depletion using clodronate liposomes during the early healing process (day 5) limited granulation tissue formation and comprised final ligament strength, even though macrophage levels returned to normal after day five [82]. de la Durantaye et al. injected mice four hours prior to tenotomy with clodronate liposomes, with daily injections until four days post-surgery, and found a decreased extracellular matrix formation and cell proliferation compared to PBS-treated mice [83]. However, it was reported that clodronate-treated mice had greater Young’s modulus and maximal stress than PBS-treated mice. The superior ultimate tensile stress in clodronate-treated mice appears to contradict the findings of Schlundt et al. [84]. Yet, this could be explained by the fact that clodronate treatment was limited to four days post-surgery, thus mainly affecting M1 macrophage levels, which is the first subset to invade tissues. After an injury, an acute inflammatory reaction is usually accompanied by extensive M1 macrophage infiltration, which secretes pro-inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β) to increase vessel wall permeability, recruit leukocytes and fibroblasts [85]. M1 macrophages have also been reported to inhibit chondrogenesis, exacerbate experimental osteoarthritis [86] and inhibit the tenogenic differentiation of tendon-derived stem cells [87]. Afterwards, macrophages are polarised into the M2 phenotype which secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines (TGF-β, IL-10) for inflammation resolution and repair. However, excessive M1 macrophage activity encourages excessive fibroblast activity, leading to scar tissue formation. This hampers tissue remodelling at tendon–bone interfaces and fibrocartilage repair, whilst increasing fibrosis and tendon adhesion [88]. This suggests that excessive M1 macrophage activity is likely responsible for the inferior mechanical properties of Achilles tendons in the study by de la Durantaye et al. [83].

Shi et al. used an Achilles tendon murine model and showed that seven days after tenotomy, bone marrow MSC-derived exosomes (BMSC-exos) increased Arg1+ M2 macrophages and decreased iNOS+ M1 macrophages [28]. In an in vitro study, Chamberlain et al. generated EEVs, which were M2-like macrophages, by exposing CD14+ macrophages to EVs [31]. The functional benefits conferred by an increased M2:M1 macrophage ratio was shown macroscopically by reduced scar hyperplasia in the BMSC-exos treated group and histologically by an increased Safranin O-positive area, suggesting increased regeneration at the tendon–bone interface. Finally, the BMSC-exos treated group enjoyed increased maximum force and Young’s modulus compared to controls, with no significant difference with the normal group [28]. Nevertheless, TGF-β secreted by M2 macrophages can promote fibrosis and pathological scarring. The persistence of M2 macrophages at the injury site can result in rebound localised fibrosis and the incomplete resolution of inflammation after a tendon injury, as shown by decreased lipoxin A4 production [89]. Li et al. showed that hydroxycamptothecin (HCPT)-primed EVs or unprimed EVs reduced TGF-β1 mediated cell proliferation compared to the control group, with HCPT-EVs almost abolishing TGF-β1 mediated fibroblast proliferation [33]. This was shown histologically by reduced collagen III and α-SMA expression. Furthermore, MSC-EV modulation of macrophage polarisation can be context dependent. Systemic administration of IL-1β-primed MSCs increased macrophage M2 polarisation and increased the survival rate of murine sepsis only in the presence of miR-146a. Exosome-mediated transfer of miR-146a was shown to be necessary for the immunomodulatory response of MSCs [36]. Proteomics has also identified differences in the fibrotic potential of EVs harvested from different tissue, with tendon fibroblast-derived EVs containing a much higher amount of TGFβ1 than EVs from myoblasts and muscle fibroblasts. Nevertheless, Xu et al. reported that TGFβ is necessary for tendon-derived stem cell (TSC) exosomes to induce MSCs to secrete type I collagen [90]; this was confirmed by a rat Achilles collagenase-indued tendinopathy model, which reported a more ordered collagen fibre arrangement and increased ultimate stress and maximum loading [34].

4.4. In Vivo Findings

No standardised histological or immunohistochemical tests were used across the studies. Gissi et al. utilised a semi-quantitative histomorphometric scoring system [29] that was modified from that proposed by Soslowsky et al., Svensson et al., and Cook et al. [93,127,128]. This considered four parameters, namely cartilage formation, vascularity, cellularity, and fibre structure. Yu et al. defined their own unique histological scoring system with six parameters [27]. Both Yao et al. and Li et al. utilised the same histological adhesion scoring system and histological healing scoring system; the former took into account the percentage of adhesion area on the tendon surface, and the latter was based on whether or not the collagen fibres looked smooth and regular [30,33]. Although many histological scoring systems overlap in the parameters they look for, they nevertheless present difficulty in pooling data, precluding any meta-analysis.

The organization of fibrous connective tissue within the defect site was evaluated using a parallel fibre alignment scoring method [129]. While the histological grading methods have been proven in vitro to be hallmarks of better healing, there are no studies directly linking histological evidence of healing to mechanical strength. Yao et al. showed that the exosome treated group had significantly decreased COL III, α-SMA, p-p65, and COX2 expression; however, these favourable immunohistochemical tests did not translate into improved maximal tensile strength [30]. Similarly, Chamberlain et al. showed that exosome treatment increased type I and type III collagen production within the granulation tissue; however, it did not significantly improve mechanical function [31]. Li et al. demonstrated that both unprimed EVs treatment and HCPT-EVs treatment dramatically lowered the adhesion grade of the tendon; however, this did not increase the maximal tensile strength of the regenerated tendon [33].

Biomechanical properties are the ultimate index for evaluating tendon–bone healing. Although the animal models varied by species, joint and time post-EV delivery, when the tendons were harvested for biomechanical testing, the methods used were very similar across all studies (Table 4). All loaded tendons into universal testing machines and stretched them to failure at a constant speed. Wang et al. [35] removed sutures prior to biomechanical testing, allowing for the accurate testing of the repaired tendon segment. Challenges exist with biomechanical testing of tendons. Many lab animals are quadrupeds and subject their tendons to different magnitudes of load than their human counterparts, making it difficult to replicate the pathology seen clinically. For all included studies, mechanical properties were assessed in vitro after tendon dissection and removal of surrounding tissue. Ex vivo testing of viable tendon samples provides information concerning the initial cellular and matrix response to loading but still cannot take into account in vivo healing. The in vitro testing methods discussed thus far can provide very controlled loading conditions, but cannot mirror the complexity of the native tissue environment. In vivo, so-called animal overuse models, overcome this by enabling the consideration of cellular responses within the native tissue environment. However, the degree of reproducibility of loading can be harder to control [130].

In vitro limitations include considerable issues associated with the gripping of the two tendon ends, which precludes the testing of the tendon-to-bone attachment. Testing the strength of the tendon-to-bone attachment is of considerable clinical value as rotator cuff re-tears usually develop at the junction between the tendon and the bone [131,132]. Although there are limitations with the biomechanical models used, the data reviewed is useful and all included studies faced the same limitations, making results comparable, with a trend towards improved maximum force, elastic modulus, and strength in EV treated groups.

Recommendations for future work would be the ex vivo testing of biomechanics using novel 3D-printed fixtures that exactly match the anatomies of the humerus and calcaneus to mechanically test supraspinatus tendon and Achilles tendon, respectively. Kurtaliaj et al.’s new approach eliminated artifactual gripping failures (e.g., growth plate failure rather than in the tendon), decreased overall testing time, and increased reproducibility [132]. Furthermore, it is challenging to generate models which mimic the cumulative damage seen in age or overuse related tendinopathy. The mechanically and chemically induced models used in these studies better model acute injuries. A representative pathophysiological tendon model can be established by combining mild overstimulation for a longer period of time (e.g., three weeks), mimicking the chronic situation, and acute extreme overloading and/or scratch, representing the acute injury [133].

Three studies reported no significant difference in biomechanical properties between EV-treated and control groups [30,31,33]. Yao et al. did not find a difference in terms of biomechanical strength in the exosome-treated group [30]. The maximum tensile strength was evaluated at three weeks following exosome treatment and primary repair with a 6-0 polypropylene suture. Li et al. also repaired the Achilles tendon using the 6-0 polypropylene suture and harvested it after three weeks [33]. Chamberlain et al. utilised a rat medial collateral ligament (MCL) injury model, and performed biomechanical testing 14 days post-injury [31]. The MCL was not subject to primary repair in this model. Based on these findings, we postulate that at three weeks post-injury, the tensile strength of the tendon repair was predominantly due to the tensile strength of the 6-0 polypropylene suture repair. Wang et al. found that ultimate stress and maximum loading were significantly increased in the exosome treated group compared with injury; however, they did not compare TSCs to TSC-derived EVs regarding biomechanics [34]. Only TSC versus phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and EVs versus PBS were compared, raising the possibility of reporting bias. No included studies reported stem cells versus EVs. For those studies which did report EVs having a positive impact on the biomechanics of ligament/tendon, the shortest follow-up time post-injury was four weeks. This might suggest that the effect of EVs on healing is mostly realised beyond the four-week point. Studies with a larger sample size and animals sacrificed at multiple time points to allow for biochemical and biomechanical studies need to explore this hypothesis and plot a timeline for histological and biomechanical improvement.

5. Conclusions

Tendinopathy is a common disorder that results in a significant disease burden. Regenerative approaches via tissue engineering are a promising option, especially novel cell-free therapies utilising MSC-EVs, which have been shown to be effective in in vitro studies. Randomised studies in suitable animal models that mimic human disease are necessary before progression to human trials. In this review, all included in vivo studies reported better tendon/ligament repair following MSC-EV treatment, but not all found improvements in every parameter measured. Although biomechanical properties are very relevant for assessing tendon and ligament healing, this was not consistently assessed. Even if it was assessed, evidence linking biomechanical alterations to functional improvement was weak; studies are needed that rigorously examine the underlying mechanisms for the enhancement of biomechanical properties after MSC-EV treatment. The progression of promising preclinical data to achieve successful clinical market authorisation remains a bottleneck. One hurdle for progress to the clinic is the transition from small animal research to advanced preclinical studies in large animals to test for the safety and efficacy of products. However, it is likely that there will be translational questions not completely answered by animal models as co-morbidities (e.g., obesity, smoking) will be challenging to model. Nevertheless, the studies in this review have showcased the safety and efficacy of MSC-EV therapy for tendon/ligament healing, by attenuating the initial inflammatory response and accelerating tendon matrix regeneration, providing a basis for potential clinical use in tendon/ligament repair.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells10102553

References

- Wu, F.; Nerlich, M.; Docheva, D. Tendon injuries: Basic science and new repair proposals. EFORT Open Rev. 2017, 2, 332–342.

- Parmar, K. Tendon and ligament: Basic science, injury and repair. Orthop. Trauma 2018, 32, 241–244.

- Andarawis-Puri, N.; Flatow, E.L.; Soslowsky, L.J. Tendon basic science: Development, repair, regeneration, and healing. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 780–784.

- Yuan, T.; Zhang, C.Q.; Wang, J.H. Augmenting tendon and ligament repair with platelet-rich plasma (PRP). Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2013, 3, 139–149.

- Arner, J.W.; Johannsen, A.M.; Ruzbarsky, J.J.; Godin, J.A. Open Popliteal Tendon Repair. Arthrosc. Tech. 2021, 10, e499–e505.

- Kainth, G.; Goel, A. A useful technique of using anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction jig for preparing patellar tunnel in surgical repair of extensor tendon ruptures. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2021, 103, 142–143.

- Villalba, J.; Molina-Corbacho, M.; García, R.; Martínez-Carreres, L. Home-Based Intravenous Analgesia with an Elastomeric Pump after Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Repair: A Case Series. J. PeriAnesthesia Nurs. 2021.

- Linderman, S.W.; Gelberman, R.H.; Thomopoulos, S.; Shen, H. Cell and Biologic-Based Treatment of Flexor Tendon Injuries. Oper. Tech. Orthop. 2016, 26, 206–215.

- Thomopoulos, S.; Parks, W.C.; Rifkin, D.B.; Derwin, K.A. Mechanisms of tendon injury and repair. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 832–839.

- Carlson, J.; Fox, O.; Kilby, P. Massive Chondrolysis and Joint Destruction after Artificial Anterior Cruciate Ligament Repair. Case Rep. Orthop. 2021, 2021, 1–5.

- Lim, W.L.; Liau, L.L.; Ng, M.H.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Law, J.X. Current Progress in Tendon and Ligament Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 16, 549–571.

- Ramdass, B. Ligament and Tendon Repair through Regeneration Using Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 84–88.

- Blum, B.; Bar-Nur, O.; Golan-Lev, T.; Benvenisty, N. The anti-apoptotic gene survivin contributes to teratoma formation by human embryonic stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 281–287.

- Harris, M.T.; Butler, D.L.; Boivin, G.P.; Florer, J.B.; Schantz, E.J.; Wenstrup, R.J. Mesenchymal stem cells used for rabbit tendon repair can form ectopic bone and express alkaline phosphatase activity in constructs. J. Orthop. Res. 2004, 22, 998–1003.

- Law, J.X.; Liau, L.L.; Bin Saim, A.; Yang, Y.; Idrus, R. Electrospun Collagen Nanofibers and Their Applications in Skin Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2017, 14, 699–718.

- Bobis-Wozowicz, S.; Kmiotek, K.; Sekula, M.; Kedracka-Krok, S.; Kamycka, E.; Adamiak, M.; Jankowska, U.; Madetko-Talowska, A.; Sarna, M.; Bik-Multanowski, M.; et al. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Microvesicles Transmit RNAs and Proteins to Recipient Mature Heart Cells Modulating Cell Fate and Behavior. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 2748–2761.

- Bernardo, M.E.; Fibbe, W.E. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Sensors and Switchers of Inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402.

- Jia, Y.-J.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, L.-L.; Li, Y.-F.; Wu, K.-M.; Duan, R.-R.; Yao, Y.-B.; Jing, L.-J.; Gong, Z.; Teng, J.-F. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells protect the injured spinal cord by inhibiting pericyte pyroptosis. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 194–202, in press.

- Liao, Q.; Li, B.J.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zeng, H.; Liu, J.M.; Yuan, L.X.; Liu, G. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes osteoarthritic cartilage regeneration by BMSC-derived exosomes via modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107824.

- Wang, X.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, G.; Yan, B. The Application Potential and Advance of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Myocardial Infarction. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 1–15.

- Witwer, K.W.; Van Balkom, B.W.M.; Bruno, S.; Choo, A.; Dominici, M.; Gimona, M.; Hill, A.F.; De Kleijn, D.; Koh, M.; Lai, R.C.; et al. Defining mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived small extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1609206.

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750.

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43.

- Huang, Y.; He, B.; Wang, L.; Yuan, B.; Shu, H.; Zhang, F.; Sun, L. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote rotator cuff tendon-bone healing by promoting angiogenesis and regulating M1 macrophages in rats. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–16.

- Wang, Y.; He, G.; Guo, Y.; Tang, H.; Shi, Y.; Bian, X.; Zhu, M.; Kang, X.; Zhou, M.; Lyu, J.; et al. Exosomes from tendon stem cells promote injury tendon healing through balancing synthesis and degradation of the tendon extracellular matrix. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 5475–5485.

- Gissi, C.; Radeghieri, A.; Passeri, C.A.L.; Gallorini, M.; Calciano, L.; Oliva, F.; Veronesi, F.; Zendrini, A.; Cataldi, A.; Bergese, P.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from rat-bone-marrow mesenchymal stromal/stem cells improve tendon repair in rat Achilles tendon injury model in dose-dependent manner: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229914.

- Wang, C.; Hu, Q.; Song, W.; Yu, W.; He, Y. Adipose Stem Cell–Derived Exosomes Decrease Fatty Infiltration and Enhance Rotator Cuff Healing in a Rabbit Model of Chronic Tears. Am. J. Sports Med. 2020, 48, 1456–1464.

- Shi, Z.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, D. Extracellular vesicles from bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells regulate inflammation and enhance tendon healing. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 1–12.

- Shen, H.; Yoneda, S.; Abu-Amer, Y.; Guilak, F.; Gelberman, R.H. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the early inflammatory response after tendon injury and repair. J. Orthop. Res. 2020, 38, 117–127.

- Yu, H.; Cheng, J.; Shi, W.; Ren, B.; Zhao, F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, P.; Duan, X.; Zhang, J.; Fu, X.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote tendon regeneration by facilitating the proliferation and migration of endogenous tendon stem/progenitor cells. Acta Biomater. 2020, 106, 328–341.

- Shi, Y.; Kang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bian, X.; He, G.; Zhou, M.; Tang, K. Exosomes Derived from Bone Marrow Stromal Cells (BMSCs) Enhance Tendon-Bone Healing by Regulating Macrophage Polarization. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26.

- Chamberlain, C.S.; Kink, J.A.; Wildenauer, L.A.; McCaughey, M.; Henry, K.; Spiker, A.M.; Halanski, M.A.; Hematti, P.; Vanderby, R. Exosome-educated macrophages and exosomes differentially improve ligament healing. Stem Cells 2020, 39, 55–61.

- Li, J.; Yao, Z.; Xiong, H.; Cui, H.; Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Qian, Y.; Fan, C. Extracellular vesicles from hydroxycamptothecin primed umbilical cord stem cells enhance anti-adhesion potential for treatment of tendon injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–14.

- Yao, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Peng, S.; Ning, J.; Qian, Y.; Fan, C. MicroRNA-21-3p Engineered Umbilical Cord Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Inhibit Tendon Adhesion. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 303–316.