Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biophysics

|

Physics, Atomic, Molecular & Chemical

Non-ionising ultraviolet radiation (UVR) and ionising radiation differ in their interactions with biomolecules, resulting in varied consequences. Here we describe the underlying molecular interactions of radiation in the context of biological systems and their outcomes from exposure.

- ionising radiation

- X-rays

- UVR

- radiation

- radiotherapy

- radiobiology

1. Introduction

Radiation exists in two main forms: Electromagnetic (EM) radiation in the form of alternating electric and magnetic waves that propagate energy, and particle radiation consisting of accelerated particles such as electrons and protons. EM radiation can be broadly categorised as non-ionising and ionising. Both types may be encountered clinically or environmentally, with exposure having potentially positive or negative effects on tissues and organisms (Table 1). In the case of non-ionising radiation, exposure of skin to ultraviolet radiation (UVR), for example, may be beneficial, as a consequence of vitamin D production [1], or detrimental, due photoageing [2] and/or photocarcinogenesis [3]. UVR is considered non-ionising as it is, in general, not sufficiently energetic to remove electrons from biomolecules. In contrast, energetic, ionising electromagnetic radiation (X-rays and gamma rays) can remove electrons. The undoubted importance of controlled exposure to ionising EM radiation in medical diagnostic imaging [4] and radiotherapy [5,6] must be balanced against side effects such as secondary cancers or tissue fibrosis [7,8]. Other forms of radiation, which rely on charged particles (e.g., α, β, protons), can also interact with biological systems and are clinically important (such as in proton therapy and in cosmic radiation exposure for space exploration), but being non-electromagnetic, they lie outside the scope of this review. The reader is referred to an excellent review by Helm et al. [9].

Table 1. Human exposure to ionising and non-ionising electromagnetic radiation can come from the environment or from clinical interventions. Exposure to both types of radiation can have clear clinical benefits but may also result in detrimental biological effects.

| Type | Environmental Exposure | Clinical Exposure | Biological Consequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionising | X-rays/Gamma rays | Cosmic radiation [10], Radon gas [11] |

Diagnostic imaging [12], Radiotherapy [13] | Fibrosis [14], Carcinogenesis [15] |

| Non-ionising | UVR | Sunlight [16] | UVR Phototherapy [17] | Skin photoageing [18], Vitamin D synthesis [19] |

| Visible light | Sunlight [20] | Photodynamic therapy [21] | Ocular phototoxicity [20] | |

| Infrared | Sunlight [22] | Neural stimulation [22] | Skin photoageing [23] | |

| Radiowaves | Lightning [24] | Hyperthermia [25] | Brain activity [26] |

Most investigations into the detrimental side effects of radiation on biological tissues have largely focused on cellular damage, and in particular, the sensitivity of DNA [27,28]. Whilst acute high radiation exposure may kill cells, it has become increasingly clear that lower doses may have sub-lethal effects that are complex, difficult to eliminate and delayed (persisting over long periods of time) [2,7,29,30]. Crucially, to understand the consequences of radiation exposure and hence to potentially prevent or reverse the damage, it is necessary to characterise the interactions of radiation with not only cells but also with their complex and dynamic extracellular environment. This review considers the consequences and causative mechanisms that drive electromagnetic radiation damage in biological tissues and in the extracellular matrix (ECM) in particular. Two clinical models of interest are discussed: skin exposed to UVR in sunlight and breast tissues exposed to diagnostic and therapeutic X-rays.

Electromagnetic Radiation

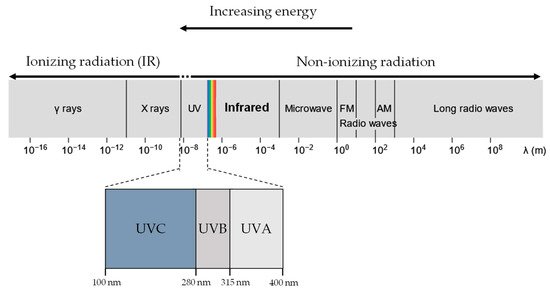

UVR and X-rays/Gamma rays, both being part of the EM radiation spectrum (Figure 1), differ only in wavelength, frequency and energy. When a molecule absorbs EM radiation, it undergoes one of three possible transitions: electronic, vibrational, or rotational [31]. In general, electronic transitions require the largest amount of energy, followed by vibrational then rotational [32].

Figure 1. UVR, X-rays and gamma rays all lie in the electromagnetic spectrum. UVR (UV-A and UV-B) lie at a slightly higher energy range compared to visible light and are generally considered non-ionising. In contrast, X-rays and gamma rays have much higher energy than UVR and are considered ionising radiation.

Ionising radiation is often more energetic than non-ionising radiation and, as a result, is more likely to induce electronic transitions of atoms and molecules. In electronic excitation, an electron absorbing the radiation transits into a higher electronic state, becoming less bounded to the nucleus and therefore more reactive [33]. If the radiation has sufficient energy, the electron can escape the coulomb attraction of the nucleus, and the molecule is ionised. In contrast, molecules undergoing rotational or vibrational transitions (generally caused by non-ionising UVR exposure) experience minimal changes in the stability of the electron-nucleus attraction, resulting in negligible chemical effects. Therefore, exposure to ionising and non-ionising radiation results in significantly distinct biological molecular effects.

2. Non-Ionising Radiation (UVR)

UVR is conventionally designated as three categories of increasing energy, UVA (315 –400 nm), UVB (280–315 nm), and UVC (10–280 nm) [34]. UVA and UVB are of particular biological interest as they comprise the UVR in sunlight at the Earth’s surface (UV-A: 95%, UV-B: 5%) [35]. In contrast, UVC is absorbed efficiently in the atmosphere by ozone and oxygen and thus plays no role in environmental UVR damage [36,37].

2.1. Absorption of Non-Ionising Radiation (UVR)

Molecules or regions of molecules that absorb UVR are referred to as UV chromophores. Biological systems are rich in UV chromophores, including DNA and some amino acid residues [38]. In DNA, the nucleotides thymine and cytosine absorb UVB to become electronically excited [39,40]. In proteins, the amino acid residues tyrosine (Tyr), tryptophan (Trp) and cystine (double-bonded cysteine) absorb UVR from sunlight [41,42], with an absorbance peak at 280 nm for Tyr and Trp and lower for cystine [43,44]. For Tyr and Trp, their benzene ring structure facilitates an electronic transition from the ground state to the singlet excitation state that requires photons in the UVB region (180–270 nm) [45,46]. The excited chromophores can then transfer their energy or donate an electron to O2, forming several reactive oxygen species (ROS) [16,47,48]. The excess energy can cleave intermolecular bonds, such as disulphide bonds, or facilitate the formation of pyrimidine dimers in DNA [49,50].

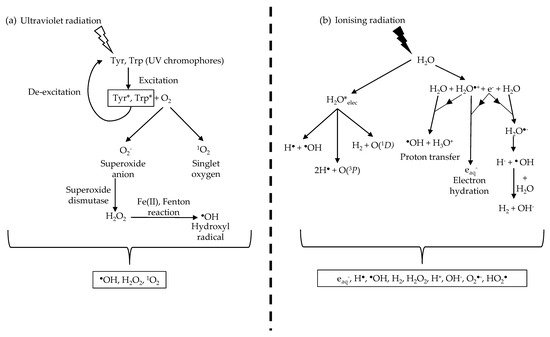

UVR damage in biological organisms is largely mediated indirectly via the photodynamic production of unstable ROS [51]. UVR exposure generates ROS via the reaction between the excited UV chromophores and molecular oxygen (O2) [2] (Figure 2). In brief, the excited UV chromophore reacts with O2 to produce, through electron transfer, either a superoxide anion radical (O2−) or singlet oxygen (1O2) through energy transfer. Superoxide dismutases, which are present in the cell [52] and the ECM [53], convert O2− into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). In the presence of Fe(II), H2O2 undergoes the Fenton reaction to generate hydroxyl radicals (HO·) [2,54]. The cellular effects of both 1O2 and HO· are well studied [47,49,54]. Intracellular ROS have been shown to react with and cause damage to both proteins and DNA [55,56].

Figure 2. UVR and ionising radiation indirectly damage biological molecules by ROS production. (a) UVR produces ROS through UV chromophores that absorb UVR and undergo excitation. The excited chromophores react with oxygen molecules to form singlet oxygen and the superoxide anion. The superoxide anion is converted to hydrogen peroxide by superoxide dismutase before undergoing the Fenton reaction in the presence of Fe (II) to form the hydroxyl radical. (b) Ionising radiation produces a range of ROS and, more crucially, the hydroxyl radical through water radiolysis. This results in a larger concentration of hydroxyl radicals produced during ionising radiation irradiation compared to UVR due to the abundance of water molecules. Information from Figure (b) was sourced from Meesungnoen J. et al. [57].

2.2. Biological Consequences of UVR Exposure

Intracellularly, UV-B photons can be absorbed directly by the DNA nucleotides thymine and cytosine to form cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) [50] and 6-4 photoproducts (6-4PP) [39]. These photoproducts can further absorb UV-A to form Dewar valence isomers [58]. CPDs, 6-4PP, and Dewar valence isomers are known as photolesions which disrupt the base pairing of DNA, preventing DNA transcription and replication [16]. Photo-dynamically produced ROS may cleave the DNA sugar backbone causing single-stranded breaks (SSB) [59] or oxidise guanine nucleotides to produce another photolesion, 8-oxoguanine, which can cause mismatched pairing between the DNA bases [48].

The ROS, 1O2 and HO· produced by UVR are strong oxidising agents that also target amino acids vulnerable to oxidation, including tryptophan [60], tyrosine [61], histidine [62], cystine [63], cysteine [64], methionine [65], arginine [66] and glycine [67]. For a more comprehensive summary of photo-oxidation of amino acids, the reader is directed to the review by Pattisson et al. [42]. Oxidation-associated changes in protein structure may, in turn, affect function [67,68,69]. UVR exposure can also break or form intermolecular bonds in proteins. In particular, di-sulphide bonded cystine can be reduced to cysteine [56]. These amino acid level changes can affect protein function, with high and low UVR doses decreasing and increasing the thermal stability of collagen, respectively [70,71,72]. UVR can also disrupt the function and structure of lipids via lipid peroxidation [73], resulting in compromised cell membranes. Extracellularly, ROS may cause damage to abundant ECM proteins, such as collagen and elastin [74,75], and to UVR-chromophore-rich proteins, such as fibrillin microfibrils and fibronectin [76]. The differential impacts of UVR exposure on the matrisome (the extracellular proteome) are discussed in detail in Section 4 and Section 5 of this review.

2.3. Repair and Prevention of UVR Damage

In response to the damage caused by UVR and/or photodynamically produced ROS, cells can initiate repair mechanisms, including nucleotide excision, to remove photolesions in the DNA [77]. Enzymes in the cell can repair reversibly oxidised proteins, such as cystine, which can be reduced back to cysteine by the thioredoxin reductase system [78], or may break down irreversibly oxidised proteins, typically products of hydroxylation and carbonylation processes [79,80]. In addition, ROS scavengers, such as superoxide dismutases, help restore the ROS balance in the intracellular and extracellular spaces by converting the superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide [53,81], which is then converted to water and oxygen by catalase and glutathione peroxidase 3 to prevent the formation of hydroxyl radicals [54,82]. We have recently proposed that the biological location of some UVR-chromophore-rich proteins (including β and γ lens crystallins, late cornified envelope proteins in the stratum corneum and elastic fibre-associated proteins in the papillary dermis) may mean that these components act as sacrificial, and hence protective, endogenous antioxidants [76].

3. Ionising Radiation (X-rays/Gamma Rays)

In the EM spectrum, ionising radiation is comprised of X-rays (0.01 nm < λ (wavelength) < 10 nm) and gamma rays (λ < 0.001 nm) (Figure 1). Naturally occurring radon gases and cosmic radiation provide a background of ionising radiation of, on average, 2.4 mSv a year [83]. On the other hand, man-made sources of ionising radiation, such as mammography, would commonly only expose the patient to a dose of 0.36 mSv per screening [84,85]. Another key source of man-made ionising radiation that is of particular interest is radiotherapy.

The efficacy of radiotherapy lies in the ability of ionising radiation to penetrate biological tissues, allowing non-invasive targeting and killing of aberrant cells by causing irreparable DNA damage. Historically, radiotherapy utilised naturally occurring sources such as Co-60, which emits 1.2 MeV gamma rays. Modern external beam radiotherapy treatment regimens use linear accelerators (linacs) to accelerate electrons towards a metal target to produce ionising radiation [86], with exposures up to doses of 50 Gy for breast cancer radiotherapy patients [87]. Other forms of radiotherapy include Brachytherapy, where a radioactive source is placed within the patient near the tumour (commonly prostate cancer) site [88]. Inadvertent exposure of healthy tissues along the irradiation path can lead to detrimental side effects, including radiation fibrosis [7] and secondary cancers [89]. While there are newer radiotherapy machines utilising proton or heavy ion beams to reduce exposures to healthy tissue by exploiting the Bragg peak [90] see Appendix A, these treatment options are less widely available and are often reserved for paediatric patients [91]. X-ray/gamma ray radiotherapy remains the foremost therapeutic option, and hence, the impact of these radiation exposures on healthy tissues is a key biological and medical issue.

3.1. Absorption of Ionising Radiation (X-rays/Gamma Rays)

In contrast to UVR, photons of ionising radiation are energetic enough to ionise most molecules and atoms [92], potentially leading to the disruption of intermolecular bonds [93]. An abundance of water molecules in biological systems results in a large percentage of ionising radiation being absorbed by water in a process called water radiolysis [94], producing multiple ROS species. Water radiolysis induces the formation of not only hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion and the hydroxyl radical [57] but also an abundance of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals [95] (Figure 2).

3.2. Biological Consequences of Exposure to Ionising Radiation

The exposure of DNA to ionising radiation may directly induce oxidation via deprotonation or electron removal, again producing photolesions such as 8-oxoguanine [96]. Hydroxyl radicals produced from water radiolysis can also disrupt the bonds in the sugar backbone of DNA, resulting in SSBs [49,97]. As ionising radiation is highly energetic, electrons ejected from radical formation could potentially cause further radiolysis of nearby water molecules, resulting in a high density of hydroxyl radicals [95,98], increasing the probability of SSB occurring close enough to each other (within 10 base pairs) to promote the formation of double-stranded breaks (DSBs) [28,99]. DSBs are potentially highly cytotoxic due to the risk of failed repair, such as in non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination, resulting in gene mutations [100,101], clastogenic effects [102], teratogenesis [103] and carcinogenesis [99].

Ionising radiation-induced water radiolysis can cause significant ROS-mediated damage to proteins through the disruption of peptide bonds, thereby altering their structure and function [67,104,105]. This leads to similar outcomes to those already described in Section 2 including both protein oxidation [106] and lipid peroxidation [107]. The direct impact of ionising radiation on proteins can be observed during X-ray diffraction studies of protein crystals, where cryogenic temperatures reduce the effects of radicals produced by the solvent [108]. These studies demonstrate that di-sulphide bonds and carboxyl groups are most susceptible to localised radiation damage [109,110]. However, this damage may not be evenly distributed throughout the protein [111]. For example, Weik et al. (2000) have shown that the specific disulphide bond between Cys-254 and Cys-265 residues for Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase, as well as the disulphide bond between Cys-6 and Cys-127 for hen egg white lysozyme, are most susceptible to radiation damage. Radiation damage may also localise at active sites in proteins [110,112,113] such as for bacteriorhodopsin [114], DNA photolyase [115], malate dehydrogenases [116], and carbonic anhydrase [117]. This damage localisation has been hypothesised to be mediated either by the presence of metal ions, which have high proton numbers and hence more electrons for photo-absorption to propagate subsequent ionisation events [118], or by the relative accessibility of exposed active sites to ROS [110]. Key extracellular protein targets of ionising radiation are discussed in Section 4 and Section 5.

3.3. Repair and Prevention of Ionising Radiation Damage

As both ionising and non-ionising radiation produce ROS, the prevention and repair of damage are largely mediated by the same mechanisms (see Section 2). However, to repair DNA damage specific to ionising radiation, cells utilise base excision repair (BER) for oxidised nucleotides, such as 8-oxoguanine [119,120], while NHEJ and homologous recombination repair (HRR) is activated to remove DSBs [121,122,123].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells10113041

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!