Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are non-steroid nuclear receptors, which dimerize with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and bind to PPAR-responsive regulatory elements (PPRE) in the promoter region of target genes. Recently, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-α and γ isoforms have been gaining consistent interest in neuropathology and treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders.

1. Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are non-steroid nuclear receptors, which dimerize with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and bind to PPAR-responsive regulatory elements (PPRE) in the promoter region of target genes (

Figure 1) [

1]. PPARs are expressed in many cellular types and tissues and exhibit differences in ligand specificity and activation of metabolic pathways [

2]. In humans, among all known transcriptional factors belonging to the nuclear receptor superfamily, three isoforms of PPARs have been characterized: PPAR-α, PPAR-β/δ, and PPAR-γ, also known as

NR1C1, NR1C2, and

NR1C3, respectively [

3]. PPARs are a target for fatty acids (unsaturated, mono-unsaturated, and poly-unsaturated), for which they mediate binding and transport, as well as oligosaccharides, polyphenols, and numerous synthetic ligands [

4]. Furthermore, they are involved in a series of molecular processes, ranging from peroxisomal regulation and mitochondrial β-oxidation to thermogenesis and lipoprotein metabolism [

5]. PPAR distribution changes in different organs and tissues. In rodent central nervous system, the three isoforms are widely co-expressed across brain areas and in circuitry that are responsible for mediating stress-responses, which supports a role in several neuropsychopathologies by mediating anti-inflammatory and metabolic actions [

6,

7]. Intriguingly, both synthetic and endogenously-produced PPAR agonists have shown benefits for treatment of mood disorders and neurological diseases [

8].

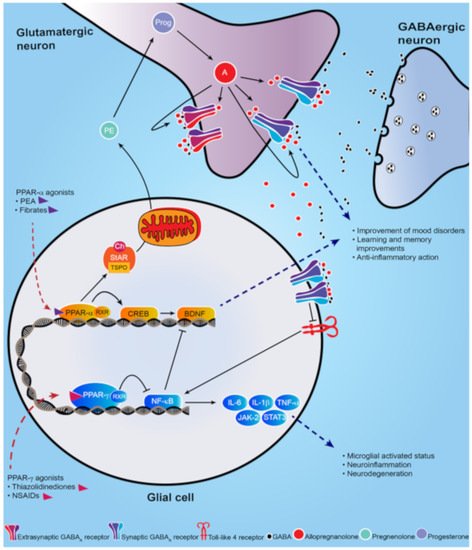

Figure 1. Schematic representation of PPAR-α and PPAR-γ signal cascade following their activation by endogenous or synthetic ligands. PPAR-α endogenous and synthetic agonists, including PEA and the fibrates, activate PPAR-α that dimerizes with the retinoid X-receptor (RXR) and activates the calcium influx through transcriptional regulation of cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB), which in turn promotes hippocampal brain derived neurotropic factor (BDNF) signaling cascade. PPAR-α activation also upregulates both the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), which forms a complex with cholesterol and translocator protein (TSPO) allowing the entry of cholesterol into the inner mitochondria membrane where cholesterol is transformed into pregnenolone (PE), the precursors of all neurosteroids, through the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc). PE, which is translocated to cortical and hippocampus glutamatergic pyramidal neurons is then converted in allopregnanolone. Allopregnanolone enhances γ-aminobutyric acid action at GABA

A receptors [

9,

10] and improves emotional behavior. Allopregnanolone may also exert an important anti-inflammatory action by binding at α2-containing GABA

A receptor subtypes located in glial cells, through inhibition of toll-like 4 receptor/NF-κB pathway [

11]. PPAR-γ agonists potentiate the PPAR-γ-induced inhibitory action on NF-κB, which is responsible for microglial activated status, neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Moreover, NF-κB inhibits the hippocampal BDNF signaling cascade [

12,

13]. Thus, PPAR-γ agonists exert an anti-inflammatory effect, by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, as well as the JAK-2/STAT3 pathway, which is involved in immunity processes. Additionally, activation of PPAR-γ plays a neuroprotective action by decreasing the inhibition on BDNF signaling pathway.

By enhancing free fatty acid uptake, PPARs may improve insulin sensitivity and beta-cell properties in hyperglycemia in patients affected with type 2 diabetes [

14]. For example, thiazolidinediones, including pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, are synthetic ligands that selectively bind at PPAR-γ and are used clinically for the treatment of diabetes [

15]. However, given their side effects on weight gain, congestive heart failure, bone fractures, and macular and peripheral edema, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has limited their use [

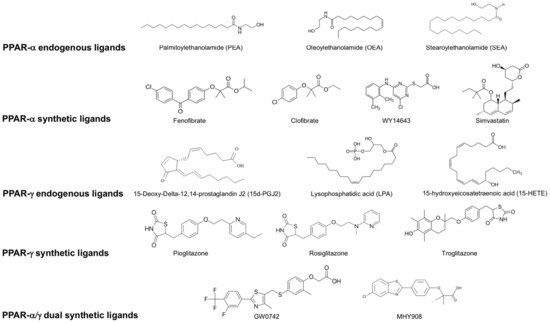

16]. PPAR-α synthetic ligands, including the fibrates (fenofibrate, clofibrate) (depicted in

Figure 2) are characterized by a much safer pharmacological profile and are widely prescribed to lower high cholesterol blood levels and triglycerides [

17]. While PPAR-α and γ endogenous and synthetic ligands have been well characterized for the treatment of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, their central neuronal effects on behavior and neuropathology have only emerged recently [

7].

Figure 2. List of endogenous and synthetic PPAR- α, PPAR-γ and dual PPAR- α/γ ligands.

The efficacy of PPAR-γ agonists on behavior was initially shown in rodent models of anxiety and depression, where the administration of rosiglitazone significantly reduced the immobility time in the forced swim test [

18]. This antidepressant effect was also observed in clinical trials where administration of pioglitazone or rosiglitazone improved symptoms in patients with major depression [

16]. Importantly, the improvement in depression correlated with normalization of inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., IL-6) and insulin resistance, suggesting an intriguing link among PPAR-γ-activation, depression, inflammation, and metabolism [

16].

These findings highlight the potential therapeutic value of PPAR-γ agonists in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders [

16,

18,

19]. Furthermore, they encourage developing new antidepressant drugs beyond the traditional selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs are relatively inefficient because they only improve symptoms in about half of patients with mood disorders, including major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [

9]. Hence, there is an urgent need for developing new treatment strategies and identifying novel neurobiological targets and biomarkers that may stimulate discovery of novel ligands [

9].

2. Brain Distribution of PPARs in the Rodent Brain

The distribution of PPARs changes over different tissues. In rat brain, the three isoforms are co-expressed during neurodevelopment. Later in life, PPAR-β/δ becomes the most predominant isoform and subsequently there is a decrease in the expression of PPAR-α and PPAR-γ [

28]. However, PPAR-α is widely expressed in amygdala, prefrontal cortex, thalamic nuclei, nucleus accumbens, ventral tegmental area, and basal ganglia [

29,

30]. In these regions, PPAR-α expression is found at the highest levels in neurons, followed by astrocytes, where it was detected in cell body and astrocytic processes, and is weakly expressed in microglia. PPAR-α is the only isotype that colocalizes with all cell types and it is the most expressed isotype in astrocytes [

30]. PPAR-β/δ has a ubiquitous distribution across the brain. It is the most widely expressed isotype both in the brain and the periphery, and studies suggest a regulatory role for PPAR-β/δ on the other isoforms [

31]. PPAR-γ is highly expressed in the amygdala, piriform cortex, dental gyrus and basal ganglia, with lower levels in thalamic nuclei and hippocampal formation [

6,

30]. PPAR-γ is also more widely expressed in neurons than astrocytes where it varies across brain regions, with higher expression in nucleus accumbens followed by the prefrontal cortex. Interestingly, PPAR-γ is not expressed in microglia of mouse or human brain unless there is a condition of a microglial functional state, as it appears after lipopolysaccharide (LPS) treatment [

30]. While PPAR-β/δ is not found in microglia, PPAR-α is the only isotype expressed under normal and LPS conditions [

30]. PPAR expression across brain areas in circuitry that regulates stress-response suggests that they may play a role in several neuropsychopathologies by mediating anti-inflammatory and metabolic actions. Intriguingly, both synthetic and endogenously-produced PPAR agonists have shown benefits for treatment of mood disorders and neurological diseases [

7,

8,

10,

32,

33].

3. Neuropsychiatric Disorders and PPARs

3.1. Mood Disorders

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects 15%–20% of the general American population, thereby representing a remarkable burden for society, exacerbated by its chronicity and comorbidity with other prevalent mood disorders, such as PTSD and suicide, and drug use disorder [

34,

35]. It is the second most common cause of disability worldwide and it is expected to become the main cause in high-income countries by 2030 [

36]. Currently, FDA-approved treatments for depression include the SSRI antidepressants and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRIs), which have a high rate of non-responders [

37]. Additionally, these medications might take up to several weeks to induce pharmacological effects and patients often drop-off treatment because of a variety of unwanted secondary effects, which comprise insomnia, headache, sexual dysfunction, and dry mouth [

38]. While novel therapeutic strategies are urgently needed for the management of MDD, PTSD, and other mood disorders, the nuclear receptors PPAR-α and γ are gaining consistent interest as new promising targets for treating behavioral dysfunction (please see

Table 1 and

Table 2 for a summary) [

39]. This is further substantiated by the recent discovery that stimulation of PPAR-α can enhance neurosteroid biosynthesis [

10], which is implicated in the etiopathology of mood disorders and their treatment [

7,

40,

41,

42,

43].

Table 1. Studies of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) ligands in models of neuropsychiatric disorders.

|

Preclinical Studies

|

|

Models of mood disorders

|

|

|

|

|

Disease

|

Model

|

Agonist

|

Molecular Target

|

Effect

|

References

|

|

Depression

|

GW-9662 treatment

|

Rosiglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Antidepressant effect; reduce the immobility time in the forced swim test

|

[18]

|

| |

Chronic social defeat stress

|

WY14643

|

PPAR-α

|

Improve depressive-like behavior in the tail suspension test and forced swim test

|

[44]

|

| |

Chronic social defeat stress

|

Fenofibrate

|

PPAR-α

|

Antidepressant-like effects

|

[45]

|

| |

CMS-exposed rats

|

Simvastatin

|

PPAR-α

|

Reverse the depression-like behaviors promoting BDNF signaling pathway

|

[46]

|

| |

CMS-exposed mice

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Decrease microglial activated status (Iba1+) and pro-inflammatory cytokines

|

[47]

|

|

PTSD

|

Socially isolated mice

|

Fenofibrate PEA

|

PPAR-α

|

Increase brain levels of allopregnanolone; Improve anxiety-like behavior; facilitate contextual fear extinction and fear extinction retention

|

[10], [48], [49]

|

|

Models of neurodevelopmental disorders

|

|

|

|

|

Schizophrenia

|

GluN1 knockdown

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve long-term memory and help restoring cognitive endophenotypes

|

[50]

|

|

ASD

|

Propionic acid autism-like rat

|

Pioglitazone (from postnatal day 24)

|

PPAR-γ

|

Mitigate the ASD-like behavior and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation

|

[51]

|

| |

VPA-autism like Wistar rat

|

Fenofibrate

|

PPAR-α

|

Reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in several brain regions

|

[52]

|

| |

BTBR

|

PEA

|

PPAR-α

|

Revert the altered phenotype and improve ASD-like behavior

|

[53]

|

| |

BTBR

|

GW0742

|

PPAR-β/δ

|

Improve repetitive behaviors and lowers thermal sensitivity responses; decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines

|

[54]

|

|

Model of neurological disorders

|

|

|

|

|

PD

|

MPTP

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Protect against neurotoxicity; decrease microglial activation and iNOS-positive cells

|

[55]

|

| |

MPTP

|

Rosiglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Protect from dopaminergic neurons loss; prevents olfactory and motor alteration

|

[56], [57]

|

| |

MPTP

|

MHY908

|

PPAR-α/γ dual agonist

|

Neuroprotective effects; reduce microglial activation and neuroinflammation

|

[58]

|

| |

MPTP

|

MDG548

|

PPAR-γ

|

Mediate neuroprotection in microglia; promote anti-inflammatory cytokines

|

[59]

|

| |

MPTP

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Decrease microglial activation and iNOS-positive cells

|

[60]

|

|

Epilepsy

|

WAG/Rij rats

|

PEA

|

PPAR-α

|

Attenuate seizures

|

[61]

|

|

AD

|

Genetically modified AD mouse

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve memory and learning deficits; prevent neurodegeneration

|

[62]

|

| |

Streptozotocin rat L165, 041 and F-L-Leu

|

L165, 041 and F-L-Leu, simultaneously

|

PPAR-β/δ and PPAR-γ,

|

Improve myelin and neuronal maturation, mitochondrial proliferation and function; decrease neuroinflammation

|

[63]

|

|

MS

|

EAE

|

Troglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Attenuate inflammation

|

[64]

|

Table 2. Effects of PPAR ligands in neuropsychiatric disorders.

|

Clinical Studies

|

|

Mood disorders

|

|

|

|

|

MDD

|

Clinical Trial

|

Rosiglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve symptoms; normalize pro-inflammatory cytokines

|

[16]

|

| |

Double-blind, randomized clinical trial; 24-week.

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve anxiety and depression

|

[65]

|

| |

Bipolar depression

|

Pioglitazone (15–30 mg/day for 8 weeks)

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve depressive symptoms

|

[66]

|

| |

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

|

Pioglitazone (15–45 mg/day for 8 weeks)

|

PPAR-γ

|

Fail to improve bipolar depression symptoms

|

[67]

|

| |

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

|

Pioglitazone (30 mg/day for 12 weeks)

|

PPAR-γ

|

Differential improvement according to metabolic and depressive status

|

[68]

|

| |

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

|

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA)

|

PPAR-α

|

Improve depressive symptoms

|

[69]

|

|

Neurodevelopmental disorders

|

|

|

|

|

ASD

|

16-week prospective study of autistic children

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

Improve repetitive and externalizing behaviors, social withdrawal

|

[70]

|

|

Neurological disorders

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

AD

|

Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial

|

Pioglitazone (45 mg/day for 18 months)

|

PPAR-γ

|

No significant effect

|

[71]

|

|

MS

|

Clinical trial, 12 month-treatment

|

Pioglitazone

|

PPAR-γ

|

No improvement in clinical symptoms; decrease grey matter atrophy

|

[72]

|

3.2. Neurodevelopmental Disorders

The involvement of PPARs in psychiatric disorders is not limited to MDD and PTSD. Schizophrenia has been associated with increased inflammation, suggesting that the neuroinflammatory processes may play a role in the pathophysiology of this prevalent mental disorder [

107]. In peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) extracted from chronic schizophrenic patients, a decreased expression and activity of PPAR-γ correlated with lower plasma levels of its endogenous ligand, 15d-prostaglandin J2, which overall indicates a state of increased inflammation [

108]. Another study in patients affected by schizophrenia investigated the expression of inflammatory and metabolic genes [

109]. Expression of PPAR-γ was increased while PPAR-α was decreased, suggesting a metabolic-inflammatory imbalance in schizophrenia [

109]. Pioglitazone provided benefits in reversing this metabolic condition. Also, administration of pioglitazone to the GluN1 knockdown model of schizophrenia improved long-term memory and helped to restore cognitive endophenotypes [

50]. Unlike most anti-psychotics, pioglitazone had a restorative effect on cognitive function (measured by the puzzle box assay), thus suggesting a potential impact of pioglitazone as an augmentation therapy in schizophrenia [

50,

110].

Consistent with a PPAR-α activation, neurobehavioral and biochemical benefits in an ASD animal model were observed following administration with fenofibrate that resulted in reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in several brain regions [

52]. PPAR-α is required for normal cerebral functions and its genetic ablation leads to repetitive behaviors and cognitive inflexibility in mice [

118]. In another rodent model of ASD, the BTBR T + tf/J (BTBR) mouse, PEA reverted the altered phenotype and improved ASD-like behavior through a PPAR-α activation. This effect was accompanied by decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines in serum, hippocampus, and colon [

53]. PEA administration restored the hippocampal BDNF signaling pathway in BTBR mice and improved mitochondrial dysfunction, which has been observed in ASD (

Table 1 and

Table 2) [

53].

PPAR-β/δ has also an effect in improving inflammation related to ASD [

119]. Treatment with the selective agonist, GW0742, improved repetitive behaviors and lowered thermal sensitivity responses in the BTBR rodents, while decreasing pro-inflammatory and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines [

54].

3.3. Neurological Disorders

In Alzheimer’s disease (AD) the deposition of amyloid β triggers neuroinflammation and oxidative damage [

122,

123]. However, the pathogenic mechanisms for AD onset and progression are far from being elucidated. For their involvement in neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and energy metabolism, PPARs have been considered as promising therapeutic target for AD (please see

Table 1 and

Table 2) [

123,

124]. PPAR-γ signaling is coordinated with the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in opposite ways. Wnt/beta-catenin is downregulated when PPAR-γ is upregulated in AD [

125]. Imbalance in the Wnt/beta-catenin/PPAR-γ regulation plays a role in physiopathology of neurological disorders owing to its involvement in oxidative stress and cell death through regulation of metabolic enzymes [

125]. Administration of pioglitazone in a genetically modified AD mouse model showed reductions in both soluble and insoluble amyloid β, while improving memory, learning deficits, and preventing neurodegeneration [

126]. However, in clinical studies, pioglitazone showed no significant effects on cognitive outcomes [

62,

71].

To remediate the effects of neurodegeneration, the agonists L165, 041, and F-L-Leu, acting on PPAR-β/δ and PPAR-γ, respectively, have been simultaneously administered in a Streptozotocin rat model of AD [

63]. The treatment improved myelin and neuronal maturation, mitochondrial proliferation, and function, while decreasing neuroinflammation, indicating a role, not only for PPAR-γ, but also for PPAR-β/δ in the pathology of AD [

63]. On the other hand, activation of PPAR-α by PEA has proven efficacy in inhibiting amylogenesis, neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and Tau hyperphosphorylation [

124]. Whether PEA could play a role alone or adjuvant of other AD therapeutics should be further investigated [

127]. The Aβ-induced tau protein hyperphosphorylation is also reduced by cannabidiol (CBD) administration, through the PPAR-γ and Wtn/β-catenin stimulation, which underscores a role for this phytocannabinoid in reducing neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [

128].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules25051062