Devastated bladder outlet (including bladder neck and posterior urethra) is defined as an entity associated with refractory, recalcitrant stenosis, significant necrosis, and/or end-stage urinary incontinence, that is deemed unfeasible for reconstruction. It can originate from neurogenic dysfunction, external trauma, or more often from complications of pelvic cancer treatments, predominantly prostate cancer.

- devastated bladder outlet

- posterior urethral stenosis

- vesicourethral anastomotic stenosis

- bladder neck contracture

- prostate cancer

- radical prostatectomy

- adverse effects

- reconstructive urology

1. Introduction and Terminology

Devastated bladder outlet (including bladder neck and posterior urethra) is defined as an entity associated with refractory, recalcitrant stenosis, significant necrosis, and/or end-stage urinary incontinence, that is deemed unfeasible for reconstruction [1]. It can originate from neurogenic dysfunction, external trauma, or more often from complications of pelvic cancer treatments, predominantly prostate cancer.

Posterior urethral stenosis (PUS) is an encompassing term describing a narrowing from the distal bladder neck to the proximal bulbar urethra, which is based on anatomical location and presence/absence of the prostate. When the prostate is present, PUS can be classified as bladder neck stenosis or contracture, prostatic urethral stenosis, and membranous/bulbomembranous urethral stenosis. The term vesicourethral anastomotic stenosis (VUAS) should be reserved for posterior urethral stenosis that usually occurs at the anastomosis after prostatectomy. The vesicourethral anastomosis is the most prevalent location of stenosis following radical prostatectomy, and the bulbomembranous urethra is the location typically affected by radiation therapy [2]. Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is a non-specific term covering all of the above.

Management of VUAS after radical prostatectomy is often simple and can be successfully treated by well-described surgical methods, either minimally invasive endoluminal procedures, or open or robotic reconstructive alternatives. The latter treatment alternatives are usually required in patients with recurrent PUS with a history of RT, which can surely result in devastated bladder outlet. In this scenario of devastated bladder outlet, these unfortunate patients are left with few easy and straightforward options: (1) they can either undergo repeated endoluminal treatments with little hope of long-term success, (2) live with a long-term indwelling catheter, or (3) undergo complex, at times extremely difficult, open/robotic reconstruction. These choices must be weighed in the presence of a good functional bladder and urinary continence status.

2. Incidence, Etiology, and Epidemiology

The detection of the accurate and realistic incidence of PUS and its most severe form, the devastated bladder outlet, resulting from prostate cancer treatments is profoundly dependent on the duration and reliability of long-term follow-up. Unfortunately, follow-up was short in most single institutional series and randomized studies rendering the exact incidence of PUS and devastated bladder outlet difficult to estimate. Jarosek et al. showed that the 10-year cumulative incidence of PUS ranged from 9.6% to 25.9%, according to etiology, i.e., EBRT (9.6%), RP (19.3%), EBRT + BT (19.4%), and RP + EBRT (25.9%) [3]. The merits of this report are a more accurate measure of PUS rates in the community rather than from single institution data, longer follow-up frames, and comparison of the incidence rates after all types of treatment.

Although occurring less frequently than VUAS in the CaPSURE study, rates of irradiation-induced stenosis were reported to rise at the time of latest follow-up, whereas post-surgery BOO plateaued after the initial 6 months of surgery [4].

The rates of BOO caused by EBRT or BT vary widely across the literature. This variation results from RT delivery modality and RT dosage protocol employed. Although current RT protocols globally showed obstruction rates similar to post-RP, combination therapy with EBRT and BT showed the highest rates at 32% after 2 years of follow-up [5]. However, Hindson et al. reported rates from 4% to 9% for combination treatment protocols [6].

Salvage treatment for prostate tumor recurrence increases the risk for BOO, as it understandably exposes the previously treated tissues to additional injury. In a small series of salvage RP after primary RT, Corcoran et al. reported VUAS rates of up to 40% [7]. However, other authors in a series of close to 200 patients achieved an obstruction rate of 22%, that was, almost half of the rates in the study by Corcoran [8]. The risk for obstruction in patients who received EBRT after RP, as either adjuvant or salvage treatment, ranged between 3% and10% [9][10]. Both salvage cryoablation and salvage HIFU also produced BOO in 5–12% and 15–30% of patients, respectively [11][12][13][14][15]. Salvage treatment protocols also carried a high risk for other severe debilitating complications such as UI, rectourethral, and urosymphyseal fistulae, for which urinary diversion with or without exenteration may be required, as not uncommonly, reconstruction is unfeasible in these settings.

3. Pathophysiology

Bladder outlet obstruction that arises after pelvic cancer treatments, predominantly RP or RT/energy-ablative treatments is believed to result from a combination of several treatment and patient factors, such as previous bladder neck or prostate procedures, surgical approaches, severe hemorrhage, significant urinary extravasation, prior radiotherapy, surgeon’s experience, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, smoking, BMI, and age [16].

It is generally agreed that post-RP VUAS occurs in the initial few months after surgery, extremely rarely after the first year, making the treatment rate of VUAS after the initial 12-month post-operative period close to nil [3][17][18]. This finding reflects that VUAS after RP is a peri-operative phenomenon, as opposed to PUS due to RT, which typically occurs several years following the insult.

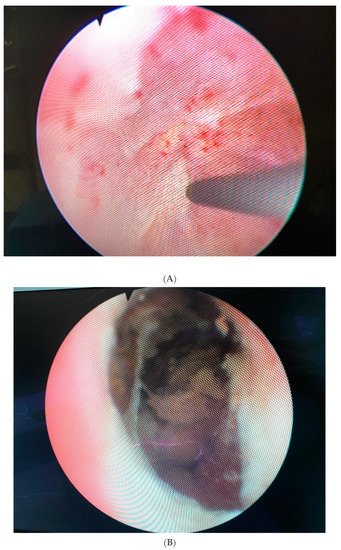

Figure 1. (A). Completely obliterated bulbomembranous stenosis (B). Fibrotic and necrotic posterior urethral tissue with calcifications caused by radiation.

Overall, EBRT, BT and cryotherapy usually result in worse PUS compared to RP, which is translated into more common and more invasive treatment modalities needed for the management of PUS after non-surgical therapies compared to PUS after surgery [6][19]. You can read more about potential consequences of radical prostatectomy, radiation therapy, and focal therapies in the article.

4. Diagnostic Evaluation and Decision Making

Diagnostic evaluation should begin with a detailed history with emphasis on filling and emptying LUTS aided by voiding diaries, validated questionnaires, details of past treatments for pelvic cancer, adjuvant or salvage radiotherapy, and previous interventions for PUS and/or UI [62]. Patients being considered for reconstruction should undergo careful examination including blood tests covering renal function parameters and PSA, urine culture and urinary cytology. Cystourethroscopy gives anatomic evaluation of the location and severity of the obstruction, degree of tissue damage with areas of calcification and necrosis, bladder stones, degree of rabdosphincter function or destruction, and concurrent neoplasms. The appearance of the bladder and bladder neck will assist in determining the salvageability of the lower urinary tract. If poor bladder capacity and compliance is suspected and if augmentation cystoplasty is considered, urodynamic evaluation should be performed [66]. Retrograde and voiding cystourethrograms are mandatory in the evaluation of PUS, especially if reconstruction is planned. These studies should complement a full endoscopic evaluation [62]. A CT scan and/or MRI of the pelvis provide relevant information regarding the anatomy as well as any concurrent diagnosis such as fistula formation, prostatic abscess or cavitation, and recurrent malignancy.

5. Management

Treatment of bladder outlet obstruction must be individualized and take several critical factors into account such as etiology of the stricture, stricture length and location, health status and wound healing capacity of local tissues, bladder urodynamic features, and continence status to maximize therapeutic success. The SIU/ICUD has recommended an algorithmic approach to the management of BOO [62]. This algorithm has multiple options, ranging from self-dilatation to open surgical reconstruction or urinary diversion. The algorithm for surgical intervention of bladder outlet obstruction can be stratified by severity, length, and location. Short, non-obliterative stenoses are treated with minimally invasive procedures and progressing to more invasive ones for recurrence, while complex stenoses should be initially, and preferentially, approached with open reconstruction, as minimally invasive alternatives are generally doomed to failure.

Endoluminal management and surgical reconstructive options are described in detail in the article.

6. Post-Reconstructive Complications

Treatments of pelvic cancer, predominantly prostate cancer, can lead to important complications such as BMUS, PUS, and VUAS. Treatment of these complications can lead to even further and more severe complications. These potential post-reconstructive complications are de novo UI (up to 50%), new onset ED (up to 35%), fistulation, and any complication of perineal and intra-abdominal surgery, including vascular and septic complications. If UI occurs, an AUS can be safely implanted even in men after RT. Urethral reconstruction appears to have minimal impact on ED. Injury of the neurovascular bundle and cavernosal bodies occurs predominantly because of oncologic treatments.

7. Conclusions

Posterior urethral obstruction, and in its more severe form a devastated bladder outlet, is a frequent adverse event of pelvic malignancy management, especially prostate cancer, with significant morbidity and detriment to patient’s QoL. To state that these posterior urethral complications can be a reconstructive challenge is surely an understatement. Radiation therapy significantly increases a negative impact on treatment outcomes. Endoluminal interventions can be considered for all patients, including after RT, due to the high potential for complications resulting from open reconstruction. In select, refractory cases, successful reconstruction with durable outcomes is feasible even for challenging RT-induced stenoses and these men should be referred to high-volume institutions with expert surgeons for treatment. Nonetheless, urinary diversion with/without extirpative surgery is indicated as a last resort when reconstruction is unfeasible or futile such as in unmotivated patients not accepting a high complication rate, in the presence of unfavorable local anatomy making reconstruction extremely difficult or impossible or in the presence of a dysfunctional bladder and a necrotic, calcified, or densely scarred bladder outlet/posterior urethra. These patients are often satisfied with the outcomes of this last resort option.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm10214920

References

- Anderson, K.M.; Higuchi, T.T.; Flynn, B.J. Management of the devastated posterior urethra and bladder neck: Refractory incontinence and stenosis. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2015, 4, 60–65.

- Mundy, A.R.; Andrich, D.E. Posterior urethral complications of the treatment of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012, 110, 304–325.

- Jarosek, S.L.; Virning, B.A.; Chu, H.; Elliott, S.P. Propensity-weighted long-term risk of urinary adverse events after prostate cancer surgery, radiation, or both. Eur. Urol. 2015, 67, 173–180.

- Elliott, S.P.; Meng, M.V.; Elkin, E.P.; McAninch, J.W.; Duchane, J.; Carroll, P. Incidence of urethral stricture after primary treatment for prostate cancer: Data from CaPSURE. J. Urol. 2007, 178, 529.

- Hindson, B.R.; Millar, J.L.; Matheson, B. Urethral strictures following high-dose-rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer: Analysis of risk factors. Brachytherapy 2013, 12, 50–55.

- Sullivan, L.; Williams, S.G.; Tai, K.H.; Faroudi, F.; Cleeve, L.; Duchesne, G.M. Urethral stricture following high dose rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 9, 232–236.

- Corcoran, N.M.; Godoy, G.; Studd, R.C.; Casey, R.G.; Hurtado-Coll, A.; Tyldesly, S.; Goldenberg, S.L.; Gleave, M.E. Salvage prostatectomy post-definitive radiation therapy: The Vancouver experience. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2013, 7, 87–92.

- Ward, J.F.; Sebo, T.J.; Blute, M.L.; Zincke, H. Salvage surgery for radiorecurrent prostate cancer: Contemporary outcomes. J. Urol. 2005, 173, 1156–1160.

- MacDonald, O.K.; Lee, R.J.; Snow, G.; Lee, C.M.; Tward, J.D.; Middleton, A.W.; Middleton, G.W.; Sause, W.T. Prostate-specific antigen control with low-dose adjuvant radiotherapy for high-risk prostate cancer. Urology 2007, 69, 295–299.

- Daly, T.; Hickey, B.E.; Lehman, M.; Francis, D.P.; See, A.M. Adjuvant radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 12, CD007234.

- Vora, A.; Agarwal, V.; Singh, P.; Patel, R.; Rivas, R.; Nething, J.; Muruve, N. Single-institution comparative study on the outcomes of salvage cryotherapy versus salvage robotic prostatectomy for radio-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2016, 4, 7–10.

- Yutkin, V.; Ahmed, H.U.; Donaldson, I.; McCartan, N.; Siddiqui, K.; Emberton, M.; Chin, J.L. Salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound for patients with recurrent prostate cancer after brachytherapy. Urology 2014, 84, 1157–1162.

- de la Taille, A.; Hayek, O.; Benson, M.C.; Bagiella, E.; Olsson, C.A.; Fatal, M.; Katz, A.E. Salvage cryotherapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy: The Columbia experience. Urology 2000, 55, 79–84.

- Kvorning Ternov, K.; Krag Jakobsen, A.; Bratt, O.; Ahlgren, G. Salvage cryotherapy for local recurrence after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Scand. J. Urol. 2015, 49, 115–119.

- Crouzet, S.; Blana, A.; Murat, F.J.; Pasticier, G.; Brown, S.C.W.; Conti, G.N.; Ganzer, R.; Chapet, O.; Gelet, A.; Chaussy, C.G.; et al. Salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for locally recurrent prostate cancer after failed radiation therapy: Multi-institutional analysis of 418 patients. BJU Int. 2017, 119, 896–904.

- Babaian, R.J.; Donnelly, B.; Bahn, D.; Baust, J.G.; Dineen, M.; Ellis, D.; Katz, A.; Pisters, L.; Rukstakis, D.; Shinohara, K.; et al. Best practice statement on cryosurgery for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 1993–2004.

- Breyer, B.N.; Davis, C.B.; Cowan, J.E.; Kane, C.J.; Carroll, P.R. Incidence of bladder neck contracture after robotic-assisted laparoscopic and open radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2010, 106, 1734–1738.

- Moltzahn, F.; Pra, A.D.; Furrer, M.; Thalmann, G.; Spahn, M. Urethral strictures after radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Investig. Clin Urol. 2016, 57, 309–315.

- Lieberman, D.; Jarosek, S.; Virnig, B.A.; Chu, H.; Elliott, S.P. The patient burden of bladder outlet obstruction after prostate cancer treatment. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 1459–1463.