Mobile health applications (MHA) are discussed to contribute in overcoming this gap in treatment by fostering CHD management. First, MHA may support daily monitoring of activities and symptoms. Second, adherence to treatment and lifestyle changes can be increased by self-tracking, feedback, and reminder functions of MHA.

- coronary heart disease (CHD)

- apps

- mobile health

- eHealth

- systematic evaluation

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases and especially coronary heart diseases (CHD) are one of the leading causes of death worldwide [1][2]. According to the global burden of disease study 17.8 million people died from cardiovascular diseases in 2017 [1]. According to the heart disease and stroke statistics the prevalence of CHD in the US ranges from 5.3% for female adults to 7.4% for male adults [3].

Disease management and behavior change including lifestyle changes are key aspects of CHD care but often not adequately and enduringly considered in care settings [4]. The large number of risk and lifestyle factors render the prevention and self-management of CHD extensive and complex for patients [4][5]. Therefore, means of promoting disease management and lifestyle changes as well as information are necessary to improve prevention and conventional treatment of CHD [4][6][7]. Mobile health applications (MHA) are discussed to contribute in overcoming this gap in treatment by fostering CHD management [6][8]. First, MHA may support daily monitoring of activities and symptoms [9]. Second, adherence to treatment and lifestyle changes can be increased by self-tracking, feedback, and reminder functions of MHA [9][10]. Third, MHA are accessible at all times and at relatively little costs [11] making MHA a scalable solution to provide general information about CHD, symptoms, and specific lifestyle modifications [12][13]. Fourth, MHA can increase patients’ perception to play an active role in their own healthcare and hereby foster self-sufficiency, disease management, and patient autonomy [9][11][14].

However, high-quality applications with suitable content are required, while the quality of MHA is largely unknown due to an intransparent MHA market and a lack of methodologically sound quality assessments [9][15]. Previous studies focused on other cardiological conditions examining the quality of MHA for heart failure [16][17], atrial fibrillation [18], and blood pressure [19]. Hereby the quality of MHA was reported as mostly acceptable [17] or mainly poor [16][19]. This is particularly alarming because MHA can also be harmful [12][15]. Risks and constraints regarding MHA concern data security, privacy, and confidentiality, since missing privacy policies and information transfer to third parties have been observed [15][20]. Furthermore, possible misinformation poses potential risks to users and the sheer number of MHA may lead to consumer confusion [4][12][21][22][23]. No evaluation of MHA specifically for CHD was found [9].

2. Research Methods

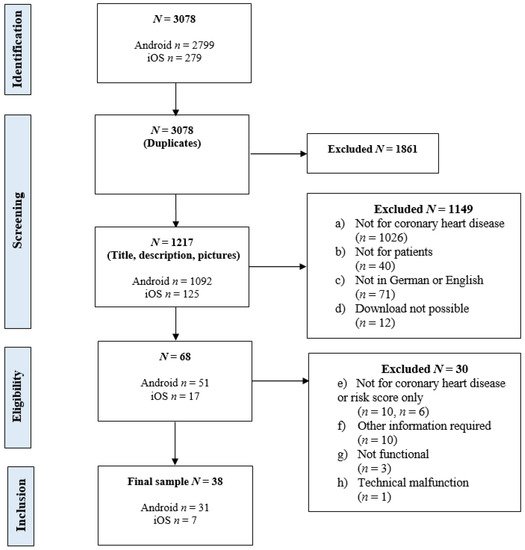

The identified MHA were examined for eligibility in a two-step procedure. In the first step, the title and app description were screened and the inclusion criteria for the download of MHA were applied. Apps were downloaded if (a) in the app title or description the subject of coronary heart disease was stated, (b) the app was developed for patients with CHD, persons at risk, or otherwise affected individuals, (c) the MHA was available in German or English language, and (d) download was possible.

In a second step, the identified apps were downloaded and the criteria for inclusion in the evaluation were examined within the app. MHA were included if (a) CHD was focused, a CHD-specific section was included, or the app description stated its use for CHD, (b) no other specific information (such as login/ access data) was required for usage of the app, (c) the application was functional, and d) there were no further technical reasons to eliminate the MHA. Technical malfunctions were tested on two devices.

For this study the MARS classification section was adapted to include the following general characteristics: (1) app name, (2) platform (Android, iOS), (3) affiliation, (4) price, (5) embedment in therapy, (6) user star rating, (7) number of user ratings, (8) app store category, (9) methods, (10) technical aspects, and (11) security and privacy.

For the quality rating with the MARS 19 items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (inadequate) to 5 (excellent). These items constitute the four dimensions: (A) engagement (five items: entertainment, interest, individual adaptability, interactivity, target group), (B) functionality (four items: performance, usability, navigation, gestural design), (C) aesthetics (three items: layout, graphics, visual appeal), and (D) information quality (seven items: accuracy of app description, goals, quality of information, quantity of information, quality of visual information, credibility, evidence base). To assess the evidence-base, for each MHA Google Scholar was searched for published studies.

3. Findings

In Figure 1 the screening and inclusion process is illustrated. A total of 3078 apps were found through the web crawler. From 1217 apps without duplicates, 38 MHA (3.12%) were included in the evaluation. Of those, 30 apps (78.95%) were available on android, seven apps (18.42%) on iOS, and one app (2.63%) for both.

The characteristics of included MHA are depicted in Table 1 . The apps were affiliated with commercial companies ( n = 20, 52.63%), non-governmental organizations (NGO; n = 2, 5.26%), universities ( n = 2, 5.26%), and governments ( n = 1, 2.63%). For 13 apps (34.21%) the affiliation was unknown. The basic version was free of cost for most apps ( n = 34, 89.47%) and required payment for four apps (10.53%) with prices ranging from EUR 1.09 to EUR 3.69 ( M = 2.57, SD = 1.08). In three apps (7.89%) an upgraded or extended pro version was available or in-app purchases were possible. No app was embedded in a treatment concept or had a certification to comply for example with the medical device regulation.

| n (%) | M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Platform Android iOS Both |

30 (78.95%) 7 (18.42%) 1 (2.63%) |

|

| Affiliation Commercial company NGO University Government Unknown |

20 (52.63%) 2 (5.26%) 2 (5.26%) 1 (2.63%) 13 (34.21%) |

|

| Obligatory payment Google Play store Apple App store |

2 (5.26%) 2 (5.26%) |

2.84 (0.85) 2.29 (1.20) |

| User ratings Google Play store Apple App store |

12 (31.58%) 1 (2.63%) |

4.26 (0.47) 1.0 (0.00) |

| Technical aspects Internet required App community |

19 (50.0%) 1 (2.63%) |

|

| Methods Information and education Tips and advice Feedback Alternative medicine Bodily exercises |

34 (89.47%) 25 (65.79%) 16 (42.11%) 3 (7.89%) 2 (5.26%) |

|

| Security & privacy Privacy policy Contact information Informed consent Login Password |

26 (68.42%) 33 (86.84%) 7 (18.42%) 6 (15.79%) 3 (7.89%) |

For 12 apps (31.58%) a user rating was available in the Google Play store and for one app (2.63%) in the Apple App store. The median user star rating in the Google Play store was 4.4 ( M = 4.26, SD = 0.47) with five to 1276 ratings ( M = 220.42, SD = 403.29) and the user star rating in the Apple App store was 1.0 with one rating (user ratings last updated on 4 April 2021). MHA were classified in eight app store categories: ‘Health & Fitness’ ( n = 18, 47.37%), ‘Medical’ ( n = 10, 26.32%), ‘Education’, ‘Books & Reference’ ( n = 3, 7.89% each), ‘Lifestyle’, ‘Food & Drink’, ‘Entertainment’, and ‘Social Networking’ ( n = 1, 2.63% each). In 19 apps (50.00%) internet was required for some or all functions and one app (2.63%) had an app community. Most common methods were information and education ( n = 34, 89.47%), tips and advice ( n = 25, 65.79%), and feedback ( n = 16, 42.11%). For most apps a privacy policy ( n = 26, 68.42%) and contact information ( n = 33, 86.84%) was provided and in seven apps (18.42%) active consent was required. Login was necessary in six apps (15.79%) and a password protection in three apps (7.89%).

The functions of the ten highest-rated apps are shown in Table 2 and a full table depicting all employed functions per MHA is included in Appendix C . In general, many MHA had one ( n = 17, 44.74%) or two functions ( n = 14, 36.84%) and in seven apps (18.42%) three or more functions were employed. Of those MHA with three or more functions, five apps (71.43%) were among the ten highest-rated apps. A significant positive correlation with a large effect size was found between the MARS total score and the number of employed functions ( r (36) = 0.66, p < 0.001).

| Provision of Information | Data Acquisition, Processing and Evaluation | Calendar and Appointment-Related | Support | Other | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | News | Reference | Learning Material | Player/Viewer | Broker | Decision Support | Calculator | Meter | Monitor | Surveillance/Tracker | Diary | Reminder | Calendar | Utility/Aid | Coach | Health Manager | Communicator/Social Network |

| CardiaCare | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | - |

| Love My Heart for Women | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - |

| CardioVisual: Heart Health Built by Cardiologists | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Heart Disease Yoga & Diet–Cardiovascular disease | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | ✓ | - |

| My Heart Age | - | ✓ | - | - | - | ✓ | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Texas Heart Institute | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| The Heart App © | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Angina | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Heart Disease 101 Audio Book | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

4. Conclusions

This first systematic evaluation of MHA for CHD demonstrated an average overall quality of MHA ( M = 3.38, SD = 0.36). The most common functions were information texts and risk score calculators. Only few MHA provide a set of multiple functions and incorporate behavior change techniques limiting the potential for lifestyle changes and support in disease management of users. Most MHA were not developed by a credible source and there is a considerable lack of scientific evidence for the usefulness and efficacy of the included MHA. Nevertheless, some potentially helpful MHA were identified.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph181910323

References

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788.

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/148114/9789241564854_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0712F3C8D5628766B719D32D4DB31713?sequence=1 (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Benjamin, E.J.; Virani, S.S.; Callaway, C.W.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Chang, A.R.; Cheng, S.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Delling, F.N.; Deo, R.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 137, 67–492.

- Hale, K.; Capra, S.; Bauer, J. A framework to assist health professionals in recommending high-quality apps for supporting chronic disease self-management: Illustrative assessment of type 2 diabetes apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015, 3, 1–12.

- Piette, J.D.; List, J.; Rana, G.K.; Townsend, W.; Striplin, D.; Heisler, M. Mobile health devices as tools for worldwide cardiovascular risk reduction and disease management. Circulation 2015, 132, 2012–2027.

- Park, L.G.; Beatty, A.; Stafford, Z.; Whooley, M.A. Mobile phone interventions for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 58, 639–650.

- Piepoli, M.F.; Corrà, U.; Dendale, P.; Frederix, I.; Prescott, E.; Schmid, J.P.; Cupples, M.; Deaton, C.; Doherty, P.; Giannuzzi, P.; et al. Challenges in secondary prevention after acute myocardial infarction: A call for action. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 1994–2006.

- Frederix, I.; Vanhees, L.; Dendale, P.; Goetschalckx, K. A review of telerehabilitation for cardiac patients. J. Telemed. Telecare 2015, 21, 45–53.

- Frederix, I.; Caiani, E.G.; Dendale, P.; Anker, S.; Bax, J.; Böhm, A.; Cowie, M.; Crawford, J.; de Groot, N.; Dilaveris, P.; et al. ESC e-Cardiology Working Group Position Paper: Overcoming challenges in digital health implementation in cardiovascular medicine. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2019, 26, 1166–1177.

- Harrison, V.; Proudfoot, J.; Wee, P.P.; Parker, G.; Pavlovic, D.H.; Manicavasagar, V. Mobile mental health: Review of the emerging field and proof of concept study. J. Ment. Health 2011, 20, 509–524.

- Pejovic, V.; Mehrotra, A.; Musolesi, M. Anticipatory mobile digital health: Towards personalised proactive therapies and prevention strategies. Anticip. Med. 2015, 253–267.

- Burke, L.E.; Ma, J.; Azar, K.M.J.; Bennett, G.G.; Peterson, E.D.; Zheng, Y.; Riley, W.; Stephens, J.; Shah, S.H.; Suffoletto, B.; et al. Current science on consumer use of mobile health for cardiovascular disease prevention: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2015, 132, 1157–1213.

- Sheridan, S.L.; Viera, A.J.; Krantz, M.J.; Ice, C.L.; Steinman, L.E.; Peters, K.E.; Kopin, L.A.; Lungelow, D. The effect of giving global coronary risk information to adults: A systematic review. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 230–239.

- Honeyman, E.; Ding, H.; Varnfield, M.; Karunanithi, M. Mobile health applications in cardiac care. Interv. Cardiol. 2014, 6, 227–240.

- Cowie, M.R.; Bax, J.; Bruining, N.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Koehler, F.; Malik, M.; Pinto, F.; Van Der Velde, E.; Vardas, P. E-Health: A position statement of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 63–66.

- Athilingam, P.; Jenkins, B. Mobile phone apps to support heart failure self-care management: Integrative review. JMIR Cardio 2018, 2.

- Creber, R.M.M.; Maurer, M.S.; Reading, M.; Hiraldo, G.; Hickey, K.T.; Iribarren, S. Review and analysis of existing mobile phone apps to support heart failure symptom monitoring and self-care management using the mobile application rating scale (MARS). JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2016, 4.

- Ayyaswami, V.; Padmanabhan, D.L.; Crihalmeanu, T.; Thelmo, F.; Prabhu, A.V.; Magnani, J.W. Mobile health applications for atrial fibrillation: A readability and quality assessment. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 293, 288–293.

- Jamaladin, H.; van de Belt, T.H.; Luijpers, L.C.H.; de Graaff, F.R.; Bredie, S.J.H.; Roeleveld, N.; van Gelder, M.M.H.J. Mobile apps for blood pressure monitoring: Systematic search in app stores and content analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018, 6.

- Zang, J.; Dummit, K.; Graves, J.; Lisker, P.; Sweeney, L. Who Knows What About Me? A Survey of Behind the Scenes Personal Data Sharing to Third Parties by Mobile Apps. Available online: https://techscience.org/a/2015103001/ (accessed on 19 September 2021).

- Nguyen, H.H.; Silva, J.N.A. Use of smartphone technology in cardiology. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 26, 376–386.

- Martínez-Pérez, B.; de la Torre-Díez, I.; López-Coronado, M.; Herreros-González, J. Mobile apps in cardiology: Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2013, 1, e15.

- Treskes, R.W.; Wildbergh, T.X.; Schalij, M.J.; Scherptong, R.W.C. Expectations and perceived barriers to widespread implementation of e-Health in cardiology practice: Results from a national survey in the Netherlands. Netherlands Hear. J. 2019, 27, 18–23.