Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), a heterogeneous tumor with poor prognosis, can arise at any level in the biliary tree. It may derive from epithelial cells in the biliary tracts and peribiliary glands and possibly from progenitor cells or even hepatocytes. Several risk factors are responsible for CCA onset, however an inflammatory milieu nearby the biliary tree represents the most common condition favoring CCA development. Chemokines play a key role in driving the immunological response upon liver injury and may sustain tumor initiation and development. Chemokine receptor-dependent pathways influence the interplay among various cellular components, resulting in remodeling of the hepatic microenvironment towards a pro-inflammatory, pro-fibrogenic, pro-angiogenic and pre-neoplastic setting. Moreover, once tumor develops, chemokine signaling may influence its progression.

- CCA

- chemokines

- Tumor Reactive Stroma

1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) comprises a heterogeneous group of biliary cancers, which can originate from cholangiocytes located at any portion of biliary tree [1]. Based on the anatomical position, this tumor can be classified in intrahepatic (iCCA) and extrahepatic (eCCA) CCA, this latter further divided into perihilar (pCCA) and distal CCA (dCCA), depending on the site within the biliary system [1,2].

CCA represents the second most frequent hepatic malignancy, accounting for 10–20% of all primary liver cancers [2,3] and its incidence is increasing dramatically [3]; accordingly, CCA mortality has increased worldwide in the last decades [4–8].

CCA is commonly asymptomatic at early stages and is often diagnosed when the disease is disseminated [9,10]. This limits the effectiveness of the current therapeutic strategies, which are preferably based on surgical resection, because antitumor drugs have only limited effects, in part owing to the high chemoresistance of this tumor [9,10]. As a result, CCA prognosis is dismal, with a 5-year survival lower than 20% [9,10].

Although the resistance to drugs is an intrinsic feature of malignant cholangiocytes [11], an additional role is played by the extensive desmoplastic microenvironment wherein neoplastic cells are embedded. Recent data support the concept that the desmoplastic stroma, that is a main feature of CCA, contributes to the decreased sensitivity of this tumor to drug-cytotoxicity, hampering responses to chemotherapy and resulting in a poor clinical outcome [1,2,4].

Although most CCAs are diagnosed de novo without an apparent liver disease background, there are well-established risk factors indicating that the appearance of CCA is favored in the context of chronic inflammatory conditions of the biliary tree (such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)) [1]. In this setting several autocrine, paracrine and endocrine signals concur to modify the environment in which tumors eventually develop: a spectrum of soluble factors (growth factors, cytokines, chemokines and proteases), released in a dysregulated fashion, sustain the inflammatory response and induce the ECM remodeling, promoting CCA initiation and progress [12]. Among these, chemokines are emerging as key factors in the complex network of events involved in development, invasiveness and immune evasion of several malignancies, including CCA.

- CCA and CCA-Associated Tumor Microenvironment

Stromal desmoplasia is a prominent histopathological hallmark of CCA that profoundly affects neoplastic ducts, contributing to CCA pathogenesis [5,6].

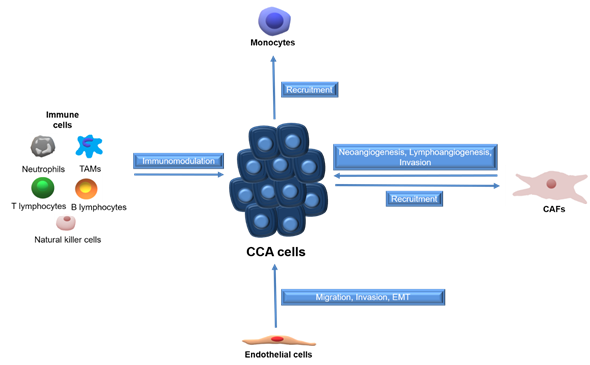

The highly reactive microenvironment is a dynamic and sophisticated compartment consisting of activated fibroblasts (cancer-associated fibroblasts, (CAFs)), endothelial and immune cells (tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), neutrophils, natural killer (NK) cells, T and B lymphocytes) embedded in a non-physiological, fibrillar ECM [1].

CAFs, the major cellular components of desmoplastic stroma, play a critical part in biliary carcinogenesis, from neoplastic transformation to tumor dissemination. Their activation is due to a wide range of soluble mediators produced by tumor cells, as well as by the multiple inflammatory cells populating the desmoplastic stroma. By secreting growth factors, cytokines and chemokines (CXCL2, CXCL12, CXCL14), CAFs recruit inflammatory and endothelial cells, sustaining neoangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis [7]. Moreover, CAFs elicit ECM structural changes, further supporting desmoplastic stroma and promoting cancer invasiveness [7].

Among the immune cell types infiltrating the desmoplastic stroma, TAMs play a crucial role in regulating angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, tumor proliferation and modulating ECM changes [1], through the release of inflammatory mediators [8].

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) represent a highly heterogeneous populations [9,10] that comprise CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, CD4+ T helper cells, Tregs and B lymphocytes. Whereas high levels of CD4+ and CD8+ within CCA microenvironment have been associated with better prognosis [10–12], low numbers of CD8+ TILs are correlated with poor overall survival [13]. Regarding B cells, no data on their pathogenic role of in CCA are available, even if high densities of CD20+ B cells have been observed in low-grade tumors and associated with a favorable overall survival [9,10]. Little is known regarding the pathogenic role of NK cells in CCA, although, according to recent studies, these cells seem to inhibit CCA growth and reduce tumor chemoresistance [11,12].

The role of neutrophils in CCA is still indefinite, even a significant commitment of infiltrated tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) in CCA tissues has been reported [14].

Tumors employ several mechanisms to establish a functional vascular system comprised of both blood and lymphatic vessels, to sustain cell growth [15,16]. CCA cells promote neo-vascularization by enhanced expression of angiogenic growth factors, whereas endothelial cells can release inflammatory chemokines to attract leukocytes and establish a pro-fibrotic and pro-angiogenic milieu, which in turn support migration, invasion and EMT [17]. The paracrine effects between CCA cells and surrounding stromal cells are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of paracrine effects between stromal cells and CCA cells. Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs), cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), cholangiocarcinoma (CCA).

- Chemokines Ligands and Receptors

Chemokines are a family of highly conserved small (8–12 kD) proteins, sharing the ability to chemoattract leukocytes. In humans, 48 chemokines have been identified, classified in four groups, according to the position of the first cysteine residues in their N-terminal sequence: XCL, CCL, CXCL and CX3CL, where X represents any other amino acid [18,19]. Chemokine signaling is transduced by G protein-coupled receptors, also divided in four groups (XCR, CCR, CXCR and CX3CR). Among the 19 receptors identified, most can bind to different chemokines, generally belonging to the same subfamily, with variable affinity and different functions [20]. Similarly, some chemokines bind and activate more than one receptor. As an important consequence of this promiscuity, chemokine-receptor interaction and the resulting signaling cascade are finely modulated, in concert with the modifications of the microenvironment.

Chemokines can also bind and activate a different category of receptors, named atypical receptors (ACKR1-6) [21], which show extreme ligand promiscuity. ACKRs lack a G protein activation motif and ligand-receptor interaction leads to β-arrestin recruitment and subsequent internalization and degradation/recycling of the ligand-receptor complex, thus serving as a chemokine reservoir or scavenger [21,23,24]. Deregulation of ACKR expression has been reported in many tumors and appears to correlate with the metastatic process [25].

Chemokines were firstly reported as key effectors of immune and inflammatory reactions, driving recruitment and homing of leukocytes into infected or injured tissues [26]. Subsequently, an essential role in several pathophysiological processes, including organ development, tissue homeostasis, angiogenesis and cancer has been recognized [27]. According to their biological functions, chemokines can be distinguished in homeostatic, which are constitutively expressed in specific cell types and contribute to immune homeostasis, and inducible, whose expression is related to certain conditions, such as inflammatory responses. Concomitantly, leukocytes express a broad spectrum of receptors, making them susceptible to many chemokine ligands [28]. In particular, CC ligands mainly act on monocytes/macrophages and T cells, while CXCL1–8 primarily exert their chemotactic action on neutrophils and CXCL9-11 on T-cells. Finally, a few chemokines display both homeostatic and pro-inflammatory functions, depending on the localization and the timing of expression [28,29].

- Regulation of Chemokine Expression and Effects

A variety of mechanisms have developed to control chemokine expression and/or activity, in order to ensure a proper cell trafficking and homing during innate and adaptive immune response. A number of polymorphisms have been identified in genes encoding chemokine and chemokine receptors, resulting in an altered expression/stability or improper ligand-receptor interaction. For instance, nine SNPs have been described in CCR2 gene, associated with various disorders, including cancer [22]. Alternative splicing of precursor mRNAs has been observed for chemokine receptors or their ligands. Splice variants can exhibit different functions and be implicated in pathological conditions, such as cancer. Interaction with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) is essential to maintain high chemokine levels in the site of release and altered chemokine binding to GAGs can result in impaired leukocytes extravasation [30]. GAG-chemokine interactions also influence the chemokine pattern and, consequently, the leukocyte populations recruited in specific areas. Finally, GAGs promote chemokine oligomerization preserving them by proteolytic cleavage and modulating chemokine-receptor linking [31]. Proteolytic cleavage can occur at either N- or C-terminal region by several proteases [32], including metalloproteases [33], dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) [34] or cathepsin B [35]. Cleaved chemokines can display either reduced or increased activity, or different receptor selectivity. Inactivation of chemokines through proteolytic cleavage may be an efficient mechanism adopted by cancer cells to evade immune response [36], as recently demonstrated for CXCL9-11 and CX3CL1 [37]. Other post-translational modifications of chemokines and their receptors include O- and N-glycosylation, citrullination, ubiquitination, sulfation, nitration and nitrosylation [22]. These processes have been shown to affect protein localization, stability and clearance, as well as their chemotactic properties [22].

- Chemokines and Cancer

Aberrant expression of chemokine ligands and receptors has been observed in several tumors, concurring to altered chemokine functions that contribute to tumorigenesis, sustained by inactivation of tumor suppressor genes, constitutive activation of transcription factors or deregulation of oncogenes regulating chemokines [38]. Indeed, in many tumors a constitutive activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) is associated with expression of chemokines that promote carcinogenesis [39]. Hypoxic conditions frequently occurring in tumor microenvironment lead to overexpression of chemokine ligands and receptors, both in cancer and stromal cells [40,41]. Cancer metabolism represents an additional element in chemokine regulation. Aerobic glycolysis and lactic acid were reported to induce NF-κB activity, and to increase CXCL8 expression and angiogenesis in breast and colon cancer [42]; ROS release has been associated with overexpression of CXCL14 and enhanced invasion and motility [43].

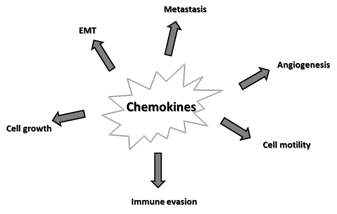

Alterations in the chemokine system are implicated in many aspects of tumorigenesis, as depicted in Figure 2 and listed below.

Figure 2. Major effects of chemokines on cancer. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

5.1. Tumor Growth

Most chemokine/GPCRs sustain cancer cell survival and proliferation, which are mainly mediated by activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [44,45] and PI3K/Akt [46] pathways. In contrast, some chemokine systems can transduce inhibitory signals, e.g., CCR1 [47] or CCR5 [48].

5.2. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

The CXCL8/CXCR1 system has been frequently associated to EMT [49–51]. Among atypical receptors, CXCR7 (ACKR3) has been reported to induce EMT and sustain tumor development in bladder cancer [46].

5.3. Angiogenesis

A high variety of chemokines directly or indirectly affect angiogenesis, with positive or negative actions. Angiogenic effects have been reported for CXCL1–3, CXCL5–6, CXCL8, CXCL12, CCL2, CCL11 and CCL16 [52,53]. In general, chemokines displaying the ELR motif, which allows leukocytes to roll on activated endothelium and migrate to the site of injury, are angiogenic [54]. Angiogenesis can be mediated by the expression of pro-angiogenic factors (such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) and others), or directly promoting endothelial cell recruitment and proliferation. Alternatively, these chemokines can recruit immune cells, as neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs), myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and TAMs [55–57] able to secrete angiogenic factors [39,58,59]. MDSCs and TAMs can even adopt endothelial cell features, contributing to vessel formation [60].

5.4. Metastasis

Changes induced by chemokines and their receptors on endothelium are crucial for cancer cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Chemokines released by the tumor microenvironment (TME) increase vessel permeability, promoting intra/extravasation and migration of malignant cells expressing the appropriate receptors and driving them to distant organs [61]. A primary role is played by TAMs, whose recruitment/activation is mainly mediated by CCL2, although other proteins, as CCL3, CCL5, CCL8 [62] or CCL18 can be also effective. Some of these molecules, e.g., CCL3, CCL8, CCL22, further sustain chemokine secretion, thus favoring the accumulation of pro-metastatic immune cells [63].

5.5. Immune Evasion

As mentioned above, many tumors express proteinases able to process and inactivate chemokines, thus impairing leukocyte recruitment and host defense [37]. Cancer cells, as well as the diverse cell types of the surrounding stroma, produce cytokines and chemokines, such as CXCL5 and CXCL8 that induce neutrophil recruitment and phenotypical transition into pro-tumorigenic MDSCs [64–66]. In the TME, MDSCs exert pro-cancer actions secreting soluble factors able to suppress TIL trafficking and anti-cancer activity [67,68].

- Chemokines and CCA

Molecular mechanisms favoring the development of a tumor reactive stroma (TRS) are crucial in the progression of CCA. Gene expression profiling of human CCA tissues identified a number of stromal-specific dysregulated genes correlated with poor clinical outcome, including genes encoding chemokines or chemokine receptors (CXCR4, CCR7, CCL2, CCL19, CCL21) [69]. CAFs have been identified as major contributors of soluble mediators with pro-tumorigenic functions, and CCA cells co-cultured with CAFs or exposed to CAF conditioned medium exhibit increased survival, proliferation and motility [70–72]. In addition, immunodeficient mice co-inoculated with CCA cells and myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) showed higher tumor development respect to animals only injected with CCA cells [73,74]. Moreover, CAF depletion in TRS reduced tumor growth in a rat model of CCA [75]. Thus, chemokines involved in the cross-talk between tumor and stroma can modulate the biological activities of cancer cells, as growth and invasiveness, acting in autocrine or paracrine fashion [64]. Soluble factors secreted by CAFs also recruit and activate inflammatory and endothelial cells, providing additional mechanisms to sustain tumor progression and metastasis [76].

Chemotactic factors released by both tumor and stromal cells contribute to recruitment and activation of TAMs [77]. Soluble mediators also induce the switch toward the M2 macrophage phenotype, although M1 and M2 features can often coexist [78]. Recently, Raggi et al. [19] have shown that CCA stem-like cells (CSC) can be involved in recruitment of circulating monocytes and their differentiation into TAMs. These CSC-associated TAMs co-express M1- (CXCL9 and CXCL10) and M2-related (CCL1chemokines, suggesting that diverse TAM subpopulations can coexist in the TRS, displaying different phenotype and functions.

Under the chemotactic action of tumor-secreted chemokines, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can be also recruited into the primary tumors. MSCs release soluble mediators that contribute to cancer progression, by promoting angiogenesis, impairing immune cell activity and increasing cancer invasiveness [79–81].

An in depth analysis of the main chemokine systems involved in biliary malignancies is presented in the review. They are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Major chemokines and their receptors involved in CCA biology.

|

Chemokine Family |

Chemokine |

Chemokine Receptor |

Target Cells |

Key Functions |

References |

|

CXCL |

CXCL12 |

CXCR4 |

CAFs CCA cells |

CCA cell survival, migration and invasion; EMT transition; metastasis; poor prognosis |

[71,82–84] |

|

CXCR7 |

CCA cells |

CCA cell adhesion, migration, invasion, growth and survival |

[85] |

||

|

CXCL7 |

CXCR2 |

CCA cells Fibroblasts Immune cells |

CCA cell proliferation and invasion; poor prognosis |

[86] |

|

|

CXCL9 |

CXCR3 |

CCA cells Immune cells Fibroblasts |

Inflammation |

[87] |

|

|

CXCL5 |

CXCR2 |

CCA cells Neutrophils |

CCA cell migration and invasion; poor prognosis; neutrophil infiltration |

[88–91] |

|

|

CCL |

CCL2 |

CCR2 |

Monocytes, Macrophages MDCs |

Immune cell migration; poor prognosis |

[77,92] |

|

CCL5 |

CCR5 |

CCA cells Immune cells Stem cells |

CCA cell migration and invasion |

[93] |

|

|

CCL20 |

CCR6 |

CCA cells Immune cells |

CCA cell migration; EMT transition |

[94,95] |

|

|

CX3CL |

CX3CL1 |

CX3CR1 |

Mononuclear cells |

Infiltration of immune cells; inflammation |

[96,97] |

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

A deep understanding of chemokine-induced molecular cascades implicated in CCA biology could be helpful to develop novel approaches to complement surgery and chemotherapy. Moreover, by interfering with pro-inflammatory, -angiogenic and -fibrogenic chemokine pathways, chemokine-based treatments might even contribute to reduce the risk to develop CCA in patients with chronic liver diseases. Understanding the roles of CCA chemokine associated molecular mechanisms could be crucial to identify predictive and prognostic biomarkers.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers12082215

References

- Gentilini, A.; Pastore, M.; Marra, F.; Raggi, C. The Role of Stroma in Cholangiocarcinoma: The Intriguing Interplay between Fibroblastic Component, Immune Cell Subsets and Tumor Epithelium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, doi:10.3390/ijms19102885.

- Chen, Z.; Guo, P.; Xie, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G. The role of tumour microenvironment: A new vision for cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 59–69, doi:10.1111/jcmm.13953.

- Pejin, B.; Jovanović, K.K.; Mojović, M.; Savić, A.G. New and highly potent antitumor natural products from marine-derived fungi: Covering the period from 2003 to 2012. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 2745–2766, doi:10.2174/15680266113136660197.

- Brivio, S.; Cadamuro, M.; Strazzabosco, M.; Fabris, L. Tumor reactive stroma in cholangiocarcinoma: The fuel behind cancer aggressiveness. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 455–468, doi:10.4254/wjh.v9.i9.455.

- Sirica, A.E.; Gores, G.J.; Groopman, J.D.; Selaru, F.M.; Strazzabosco, M.; Wei Wang, X.; Zhu, A.X. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Continuing Challenges and Translational Advances. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1803–1815, doi:10.1002/hep.30289.

- Cadamuro, M.; Brivio, S.; Spirli, C.; Joplin, R.E.; Strazzabosco, M.; Fabris, L. Autocrine and Paracrine Mechanisms Promoting Chemoresistance in Cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, doi:10.3390/ijms18010149.

- Sirica, A.E. The role of cancer-associated myofibroblasts in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 9, 44–54, doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.222.

- Roy, S.; Glaser, S.; Chakraborty, S. Inflammation and Progression of Cholangiocarcinoma: Role of Angiogenic and Lymphangiogenic Mechanisms. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 293, doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00293.

- Kasper, H.U.; Drebber, U.; Stippel, D.L.; Dienes, H.P.; Gillessen, A. Liver tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: Comparison of hepatocellular and cholangiolar carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 15, 5053–5057, doi:10.3748/wjg.15.5053.

- Goeppert, B.; Frauenschuh, L.; Zucknick, M.; Stenzinger, A.; Andrulis, M.; Klauschen, F.; Joehrens, K.; Warth, A.; Renner, M.; Mehrabi, A.; et al. Prognostic impact of tumour-infiltrating immune cells on biliary tract cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 2665–2674, doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.610.

- Jung, I.H.; Kim, D.H.; Yoo, D.K.; Baek, S.Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Jung, D.E.; Park, S.W.; Chung, Y.Y. Study of Natural Killer (NK) Cell Cytotoxicity Against Cholangiocarcinoma in a Nude Mouse Model. In Vivo 2018, 32, 771–781, doi:10.21873/invivo.11307.

- Morisaki, T.; Umebayashi, M.; Kiyota, A.; Koya, N.; Tanaka, H.; Onishi, H.; Katano, M. Combining cetuximab with killer lymphocytes synergistically inhibits human cholangiocarcinoma cells in vitro. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 2249–2256.

- Jonuleit, H.; Schmitt, E.; Schuler, G.; Knop, J.; Enk, A.H. Induction of interleukin 10-producing, nonproliferating CD4(+) T cells with regulatory properties by repetitive stimulation with allogeneic immature human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1213–1222, doi:10.1084/jem.192.9.1213.

- Tan, D.W.; Fu, Y.; Su, Q.; Guan, M.J.; Kong, P.; Wang, S.Q.; Wang, H.L. Prognostic Significance of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio in Oncologic Outcomes of Cholangiocarcinoma: A Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33789, doi:10.1038/srep33789.

- Fabris, L.; Alvaro, D. The prognosis of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma after radical treatments. Hepatology 2012, 56, 800–802, doi:10.1002/hep.25808.

- Sha, M.; Jeong, S.; Wang, X.; Tong, Y.; Cao, J.; Sun, H.Y.; Xia, L.; Xu, N.; Xi, Z.F.; Zhang, J.J.; et al. Tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis predicts unfavorable prognosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 208, doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5420-z.

- Xiao, K.; Ouyang, Z.; Tang, H.H. Inhibiting the proliferation and metastasis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma cells by blocking the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor with small interfering RNA. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 1841–1848, doi:10.3892/ol.2018.8840.

- Zlotnik, A.; Yoshie, O. Chemokines: A new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity 2000, 12, 121–127, doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x.

- Raggi, C.; Correnti, M.; Sica, A.; Andersen, J.B.; Cardinale, V.; Alvaro, D.; Chiorino, G.; Forti, E.; Glaser, S.; Alpini, G.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma stem-like subset shapes tumor-initiating niche by educating associated macrophages. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 102–115, doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.012.

- Wescott, M.P.; Kufareva, I.; Paes, C.; Goodman, J.R.; Thaker, Y.; Puffer, B.A.; Berdougo, E.; Rucker, J.B.; Handel, T.M.; Doranz, B.J. Signal transmission through the CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) transmembrane helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9928–9933, doi:10.1073/pnas.1601278113.

- Bachelerie, F.; Graham, G.J.; Locati, M.; Mantovani, A.; Murphy, P.M.; Nibbs, R.; Rot, A.; Sozzani, S.; Thelen, M. New nomenclature for atypical chemokine receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 207–208, doi:10.1038/ni.2812.

- Stone, M.J.; Hayward, J.A.; Huang, C.; E Huma, Z.; Sanchez, J. Mechanisms of Regulation of the Chemokine-Receptor Network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, doi:10.3390/ijms18020342.

- Vacchini, A.; Busnelli, M.; Chini, B.; Locati, M.; Borroni, E.M. Analysis of G Protein and β-Arrestin Activation in Chemokine Receptors Signaling. Methods Enzymol. 2016, 570, 421–440, doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2015.09.016.

- Bonecchi, R.; Savino, B.; Borroni, E.M.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. Chemokine decoy receptors: Structure-function and biological properties. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2010, 341, 15–36, doi:10.1007/82_2010_19.

- Borroni, E.M.; Savino, B.; Bonecchi, R.; Locati, M. Chemokines sound the alarmin: The role of atypical chemokine in inflammation and cancer. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 38, 63–71, doi:10.1016/j.smim.2018.10.005.

- Le, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Iribarren, P.; Wang, J. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: Their manifold roles in homeostasis and disease. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2004, 1, 95–104.

- Chen, K.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yoshimura, T.; Gong, W.; Le, Y.; Tessarollo, L.; Wang, J.M. Signal relay by CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) and formylpeptide receptor 2 (Fpr2) in the recruitment of monocyte-derived dendritic cells in allergic airway inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 16262–16273, doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.450635.

- Graham, G.J. D6 and the atypical chemokine receptor family: Novel regulators of immune and inflammatory processes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 342–351, doi:10.1002/eji.200838858.

- Zlotnik, A.; Burkhardt, A.M.; Homey, B. Homeostatic chemokine receptors and organ-specific metastasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 597–606, doi:10.1038/nri3049.

- Proudfoot, A.E.I.; Johnson, Z.; Bonvin, P.; Handel, T.M. Glycosaminoglycan Interactions with Chemokines Add Complexity to a Complex System. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, doi:10.3390/ph10030070.

- Wang, X.; Sharp, J.S.; Handel, T.M.; Prestegard, J.H. Chemokine oligomerization in cell signaling and migration. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2013, 117, 531–578, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386931-9.00020-9.

- Mortier, A.; Van Damme, J.; Proost, P. Regulation of chemokine activity by posttranslational modification. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 120, 197–217, doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.08.006.

- Starr, A.E.; Dufour, A.; Maier, J.; Overall, C.M. Biochemical analysis of matrix metalloproteinase activation of chemokines CCL15 and CCL23 and increased glycosaminoglycan binding of CCL16. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 5848–5860, doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.314609.

- Mortier, A.; Van Damme, J.; Proost, P. Overview of the mechanisms regulating chemokine activity and availability. Immunol. Lett. 2012, 145, 2–9, doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2012.04.015.

- Bronger, H.; Karge, A.; Dreyer, T.; Zech, D.; Kraeft, S.; Avril, S.; Kiechle, M.; Schmitt, M. Induction of cathepsin B by the CXCR3 chemokines CXCL9 and CXCL10 in human breast cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 4224–4230, doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5994.

- Barreira da Silva, R.; Laird, M.E.; Yatim, N.; Fiette, L.; Ingersoll, M.A.; Albert, M.L. Dipeptidylpeptidase 4 inhibition enhances lymphocyte trafficking, improving both naturally occurring tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 850–858, doi:10.1038/ni.3201.

- Bronger, H.; Magdolen, V.; Goettig, P.; Dreyer, T. Proteolytic chemokine cleavage as a regulator of lymphocytic infiltration in solid tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 417–430, doi:10.1007/s10555-019-09807-3.

- Sarvaiya, P.J.; Guo, D.; Ulasov, I.; Gabikian, P.; Lesniak, M.S. Chemokines in tumor progression and metastasis. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 2171–2185, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.1426.

- Richmond, A. Nf-kappa B, chemokine gene transcription and tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 664–674, doi:10.1038/nri887.

- Schioppa, T.; Uranchimeg, B.; Saccani, A.; Biswas, S.K.; Doni, A.; Rapisarda, A.; Bernasconi, S.; Saccani, S.; Nebuloni, M.; Vago, L.; et al. Regulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 by hypoxia. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1391–1402, doi:10.1084/jem.20030267.

- Staller, P.; Sulitkova, J.; Lisztwan, J.; Moch, H.; Oakeley, E.J.; Krek, W. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 downregulated by von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor pVHL. Nature 2003, 425, 307–311, doi:10.1038/nature01874.

- Végran, F.; Boidot, R.; Michiels, C.; Sonveaux, P.; Feron, O. Lactate influx through the endothelial cell monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 supports an NF-κB/IL-8 pathway that drives tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2550–2560, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2828.

- Pelicano, H.; Lu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Y.; Huang, P. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species imbalance promote breast cancer cell motility through a CXCL14-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2375–2383, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3359.

- Zhou, Y.; Larsen, P.H.; Hao, C.; Yong, V.W. CXCR4 is a major chemokine receptor on glioma cells and mediates their survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 49481–49487, doi:10.1074/jbc.M206222200.

- Barbero, S.; Bonavia, R.; Bajetto, A.; Porcile, C.; Pirani, P.; Ravetti, J.L.; Zona, G.L.; Spaziante, R.; Florio, T.; Schettini, G. Stromal cell-derived factor 1alpha stimulates human glioblastoma cell growth through the activation of both extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 and Akt. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 1969–1974.

- Murakami, T.; Cardones, A.R.; Finkelstein, S.E.; Restifo, N.P.; Klaunberg, B.A.; Nestle, F.O.; Castillo, S.S.; Dennis, P.A.; Hwang, S.T. Immune evasion by murine melanoma mediated through CC chemokine receptor-10. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1337–1347, doi:10.1084/jem.20030593.

- Lu, P.; Nakamoto, Y.; Nemoto-Sasaki, Y.; Fujii, C.; Wang, H.; Hashii, M.; Ohmoto, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Mukaida, N. Potential interaction between CCR1 and its ligand, CCL3, induced by endogenously produced interleukin-1 in human hepatomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 162, 1249–1258, doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63921-1.

- Mañes, S.; Mira, E.; Colomer, R.; Montero, S.; Real, L.M.; Gómez-Moutón, C.; Jiménez-Baranda, S.; Garzón, A.; Lacalle, R.A.; Harshman, K.; et al. CCR5 expression influences the progression of human breast cancer in a p53-dependent manner. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1381–1389, doi:10.1084/jem.20030580.

- Bates, R.C.; DeLeo, M.J.; Mercurio, A.M. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colon carcinoma involves expression of IL-8 and CXCR-1-mediated chemotaxis. Exp. Cell Res. 2004, 299, 315–324, doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.05.033.

- Bertran, E.; Caja, L.; Navarro, E.; Sancho, P.; Mainez, J.; Murillo, M.M.; Vinyals, A.; Fabra, A.; Fabregat, I. Role of CXCR4/SDF-1 alpha in the migratory phenotype of hepatoma cells that have undergone epithelial-mesenchymal transition in response to the transforming growth factor-beta. Cell Signal. 2009, 21, 1595–1606, doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.06.006.

- Hwang, W.L.; Yang, M.H.; Tsai, M.L.; Lan, H.Y.; Su, S.H.; Chang, S.C.; Teng, H.W.; Yang, S.H.; Lan, Y.T.; Chiou, S.H.; et al. SNAIL regulates interleukin-8 expression, stem cell-like activity, and tumorigenicity of human colorectal carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 279–291, 291.e271-275, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.008.

- Kiefer, F.; Siekmann, A.F. The role of chemokines and their receptors in angiogenesis. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 2811–2830, doi:10.1007/s00018-011-0677-7.

- Mehrad, B.; Keane, M.P.; Strieter, R.M. Chemokines as mediators of angiogenesis. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 97, 755–762.

- Burger, J.A.; Tsukada, N.; Burger, M.; Zvaifler, N.J.; Dell'Aquila, M.; Kipps, T.J. Blood-derived nurse-like cells protect chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells from spontaneous apoptosis through stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood 2000, 96, 2655–2663.

- Lazennec, G.; Richmond, A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: New insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol. Med. 2010, 16, 133–144, doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2010.01.003.

- Singh, S.; Wu, S.; Varney, M.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, R.K. CXCR1 and CXCR2 silencing modulates CXCL8-dependent endothelial cell proliferation, migration and capillary-like structure formation. Microvasc. Res. 2011, 82, 318–325, doi:10.1016/j.mvr.2011.06.011.

- Lewis, C.E.; Pollard, J.W. Distinct role of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 605–612, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4005.

- Mantovani, A.; Schioppa, T.; Porta, C.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 315–322, doi:10.1007/s10555-006-9001-7.

- Sozzani, S.; Rusnati, M.; Riboldi, E.; Mitola, S.; Presta, M. Dendritic cell-endothelial cell cross-talk in angiogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 385–392, doi:10.1016/j.it.2007.07.006.

- Rehman, J.; Landman, J.; Sundaram, C.; Clayman, R.V. Tissue chemoablation. J. Endourol. 2003, 17, 647–657, doi:10.1089/089277903322518662.

- Wolf, M.J.; Hoos, A.; Bauer, J.; Boettcher, S.; Knust, M.; Weber, A.; Simonavicius, N.; Schneider, C.; Lang, M.; Stürzl, M.; et al. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2-Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 91–105, doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.023.

- Halvorsen, E.C.; Hamilton, M.J.; Young, A.; Wadsworth, B.J.; LePard, N.E.; Lee, H.N.; Firmino, N.; Collier, J.L.; Bennewith, K.L. Maraviroc decreases CCL8-mediated migration of CCR5(+) regulatory T cells and reduces metastatic tumor growth in the lungs. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1150398, doi:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1150398.

- Kitamura, T.; Pollard, J.W. Therapeutic potential of chemokine signal inhibition for metastatic breast cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 100, 266–270, doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.08.004.

- Verbeke, H.; Struyf, S.; Laureys, G.; Van Damme, J. The expression and role of CXC chemokines in colorectal cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 345–358, doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.09.002.

- Haider, C.; Hnat, J.; Wagner, R.; Huber, H.; Timelthaler, G.; Grubinger, M.; Coulouarn, C.; Schreiner, W.; Schlangen, K.; Sieghart, W.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β and Axl Induce CXCL5 and Neutrophil Recruitment in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2019, 69, 222–236, doi:10.1002/hep.30166.

- Najjar, Y.G.; Rayman, P.; Jia, X.; Pavicic, P.G.; Rini, B.I.; Tannenbaum, C.; Ko, J.; Haywood, S.; Cohen, P.; Hamilton, T.; et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cell Subset Accumulation in Renal Cell Carcinoma Parenchyma Is Associated with Intratumoral Expression of IL1β, IL8, CXCL5, and Mip-1α. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 2346–2355, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1823.

- Lecot, P.; Sarabi, M.; Pereira Abrantes, M.; Mussard, J.; Koenderman, L.; Caux, C.; Bendriss-Vermare, N.; Michallet, M.C. Neutrophil Heterogeneity in Cancer: From Biology to Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2155, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02155.

- Granot, Z. Neutrophils as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1710, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01710.

- Andersen, J.B.; Spee, B.; Blechacz, B.R.; Avital, I.; Komuta, M.; Barbour, A.; Conner, E.A.; Gillen, M.C.; Roskams, T.; Roberts, L.R.; et al. Genomic and genetic characterization of cholangiocarcinoma identifies therapeutic targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1021–1031.e1015, doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.005.

- Heits, N.; Heinze, T.; Bernsmeier, A.; Kerber, J.; Hauser, C.; Becker, T.; Kalthoff, H.; Egberts, J.H.; Braun, F. Influence of mTOR-inhibitors and mycophenolic acid on human cholangiocellular carcinoma and cancer associated fibroblasts. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 322, doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2360-8.

- Gentilini, A.; Rombouts, K.; Galastri, S.; Caligiuri, A.; Mingarelli, E.; Mello, T.; Marra, F.; Mantero, S.; Roncalli, M.; Invernizzi, P.; et al. Role of the stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)-CXCR4 axis in the interaction between hepatic stellate cells and cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 813–820, doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2012.06.012.

- Okabe, H.; Beppu, T.; Hayashi, H.; Horino, K.; Masuda, T.; Komori, H.; Ishikawa, S.; Watanabe, M.; Takamori, H.; Iyama, K.; et al. Hepatic stellate cells may relate to progression of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 2555–2564, doi:10.1245/s10434-009-0568-4.

- Claperon, A.; Mergey, M.; Aoudjehane, L.; Ho-Bouldoires, T.H.; Wendum, D.; Prignon, A.; Merabtene, F.; Firrincieli, D.; Desbois-Mouthon, C.; Scatton, O.; et al. Hepatic myofibroblasts promote the progression of human cholangiocarcinoma through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Hepatology 2013, 58, 2001–2011, doi:10.1002/hep.26585.

- Okabe, H.; Beppu, T.; Hayashi, H.; Ishiko, T.; Masuda, T.; Otao, R.; Horlad, H.; Jono, H.; Ueda, M.; Shinriki, S.; et al. Hepatic stellate cells accelerate the malignant behavior of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1175–1184, doi:10.1245/s10434-010-1391-7.

- Mertens, J.C.; Fingas, C.D.; Christensen, J.D.; Smoot, R.L.; Bronk, S.F.; Werneburg, N.W.; Gustafson, M.P.; Dietz, A.B.; Roberts, L.R.; Sirica, A.E.; et al. Therapeutic effects of deleting cancer-associated fibroblasts in cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 897–907, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2130.

- Cadamuro, M.; Morton, S.D.; Strazzabosco, M.; Fabris, L. Unveiling the role of tumor reactive stroma in cholangiocarcinoma: An opportunity for new therapeutic strategies. Transl. Gastrointest. Cancer 2013, 2, 130–144, doi:10.3978/j.issn.2224-4778.2013.04.02.

- Yang, X.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, W.; Yin, W.; Dang, Y.; Chu, Y.; Fan, J.; He, R. FAP Promotes Immunosuppression by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in the Tumor Microenvironment via STAT3-CCL2 Signaling. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 4124–4135, doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2973.

- Sica, A.; Invernizzi, P.; Mantovani, A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in liver homeostasis and pathology. Hepatology 2014, 59, 2034–2042, doi:10.1002/hep.26754.

- Haga, H.; Yan, I.K.; Takahashi, K.; Wood, J.; Zubair, A.; Patel, T. Tumour cell-derived extracellular vesicles interact with mesenchymal stem cells to modulate the microenvironment and enhance cholangiocarcinoma growth. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 24900, doi:10.3402/jev.v4.24900.

- Wang, W.; Zhong, W.; Yuan, J.; Yan, C.; Hu, S.; Tong, Y.; Mao, Y.; Hu, T.; Zhang, B.; Song, G. Involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the mesenchymal stem cells promote metastatic growth and chemoresistance of cholangiocarcinoma. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 42276–42289, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.5514.

- Chen, F.; Zhuang, X.; Lin, L.; Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hu, G.; Sun, Y. New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: Challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 45, doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0278-7.

- Ohira, S.; Itatsu, K.; Sasaki, M.; Harada, K.; Sato, Y.; Zen, Y.; Ishikawa, A.; Oda, K.; Nagasaka, T.; Nimura, Y.; et al. Local balance of transforming growth factor-beta1 secreted from cholangiocarcinoma cells and stromal-derived factor-1 secreted from stromal fibroblasts is a factor involved in invasion of cholangiocarcinoma. Pathol. Int. 2006, 56, 381–389, doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01982.x.

- Okamoto, K.; Tajima, H.; Nakanuma, S.; Sakai, S.; Makino, I.; Kinoshita, J.; Hayashi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Oyama, K.; Nakagawara, H.; et al. Angiotensin II enhances epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through the interaction between activated hepatic stellate cells and the stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 axis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2012, 41, 573–582, doi:10.3892/ijo.2012.1499.

- Miyata, T.; Yamashita, Y.I.; Yoshizumi, T.; Shiraishi, M.; Ohta, M.; Eguchi, S.; Aishima, S.; Fujioka, H.; Baba, H. CXCL12 expression in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 3197–3203, doi:10.1111/cas.14151.

- Gentilini, A.; Caligiuri, A.; Raggi, C.; Rombouts, K.; Pinzani, M.; Lori, G.; Correnti, M.; Invernizzi, P.; Rovida, E.; Navari, N.; et al. CXCR7 contributes to the aggressive phenotype of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2246–2256, doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.04.020.

- Guo, Q.; Jian, Z.; Jia, B.; Chang, L. CXCL7 promotes proliferation and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1114–1122, doi:10.3892/or.2016.5312.

- Fukuda, Y.; Asaoka, T.; Eguchi, H.; Yokota, Y.; Kubo, M.; Kinoshita, M.; Urakawa, S.; Iwagami, Y.; Tomimaru, Y.; Akita, H.; et al. Endogenous CXCL9 affects prognosis by regulating tumor-infiltrating natural killer cells in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 323–333, doi:10.1111/cas.14267.

- Veenstra, M.; Ransohoff, R.M. Chemokine receptor CXCR2: Physiology regulator and neuroinflammation controller? J. NeuroImmunol. 2012, 246, 1–9, doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.02.016.

- Zhou, S.L.; Dai, Z.; Zhou, Z.J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.S.; Hu, Z.Q.; Huang, X.Y.; Yang, G.H.; Shi, Y.H.; et al. CXCL5 contributes to tumor metastasis and recurrence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by recruiting infiltrative intratumoral neutrophils. Carcinogenesis 2014, 35, 597–605, doi:10.1093/carcin/bgt397.

- Hu, B.; Fan, H.; Lv, X.; Chen, S.; Shao, Z. Prognostic significance of CXCL5 expression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2018, 18, 68, doi:10.1186/s12935-018-0562-7.

- Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, S.T.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H.; Park, J.O.; Kang, W.K.; Park, Y.S.; Lim, H.Y. The Correlation Between Serum Chemokines and Clinical Outcome in Patients with Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 353–357, doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2018.01.007.

- Yoshimura, T. The chemokine MCP-1 (CCL2) in the host interaction with cancer: A foe or ally? Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 335–345, doi:10.1038/cmi.2017.135.

- Liu, G.T.; Chen, H.T.; Tsou, H.K.; Tan, T.W.; Fong, Y.C.; Chen, P.C.; Yang, W.H.; Wang, S.W.; Chen, J.C.; Tang, C.H. CCL5 promotes VEGF-dependent angiogenesis by down-regulating miR-200b through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 10718–10731, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.2532.

- Comerford, I.; Bunting, M.; Fenix, K.; Haylock-Jacobs, S.; Litchfield, W.; Harata-Lee, Y.; Turvey, M.; Brazzatti, J.; Gregor, C.; Nguyen, P.; et al. An immune paradox: How can the same chemokine axis regulate both immune tolerance and activation?: CCR6/CCL20: A chemokine axis balancing immunological tolerance and inflammation in autoimmune disease. Bioessays 2010, 32, 1067–1076, doi:10.1002/bies.201000063.

- Maung, H.M.W.; Chan-On, W.; Kunkeaw, N.; Khaenam, P. Common transcriptional programs and the role of chemokine (CC motif) ligand 20 (CCL20) in cell migration of cholangiocarcinoma. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 154–166, doi:10.17179/excli2019-1893.

- Isse, K.; Harada, K.; Zen, Y.; Kamihira, T.; Shimoda, S.; Harada, M.; Nakanuma, Y. Fractalkine and CX3CR1 are involved in the recruitment of intraepithelial lymphocytes of intrahepatic bile ducts. Hepatology 2005, 41, 506–516, doi:10.1002/hep.20582.

- Sasaki, M.; Ikeda, H.; Sato, Y.; Nakanuma, Y. Decreased expression of Bmi1 is closely associated with cellular senescence in small bile ducts in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 831–845, doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.051237.