Goat meat is the main source of animal protein in developing countries, particularly in Asia and Africa. Goat meat consumption has also increased in the US in the recent years due to the growing ethnic population. The digestive tract of goat is a natural habitat for Escherichia coli organisms. While researchers have long focused on postharvest intervention strategies to control E. coli outbreaks, recent works have also included preharvest methodologies. In goats, these include minimizing animal stress, manipulating diet a few weeks prior to processing, feeding diets high in tannins, controlling feed deprivation times while preparing for processing, and spray washing goats prior to slaughter.

1. Introduction

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (E. coli) is considered one of the most economically important food-borne pathogens. Much of the research has focused on post-slaughter sanitation to improve the safety of meat products, and as a result, various strategies are practiced in meat plants to reduce carcass contamination. In recent years, researchers have also been working on developing intervention strategies in the live animal prior to slaughter to reduce foodborne pathogens. Because fecal shedding is correlated with carcass contamination, reducing bacterial loads in the gastrointestinal tracts of live animals is important in the production of safe and wholesome food products.

It is widely recognized that hygienic risks at slaughterhouses should be assessed in reference to the number of organisms indicative of fecal contamination [

1]. The Agricultural Marketing Service of the US Department of Agriculture has established 500 CFU g

−1 as a critical limit for generic

E. coli in red meat such as beef [

2]. Although

E. coli organisms are normal inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tracts of ruminants, some pathogenic strains can cause hemorrhagic colitis in humans [

3].

Escherichia coli O157:H7 is the most common enterohemorrhagic

E. coli serotype implicated in many outbreaks of bloody diarrhea and the hemolytic–uremic syndrome resulting in kidney failure.

Goat meat is one of the most widely consumed meats in the world, especially in Asia and Africa, and importation of goat meat into the US has steadily increased mainly due to increased demand by ethnic consumers. However, research on intervention strategies to reduce pathogens in goat carcasses, cuts, and products is very limited. Data available on preslaughter intervention strategies to reduce foodborne pathogens in goats are scanty.

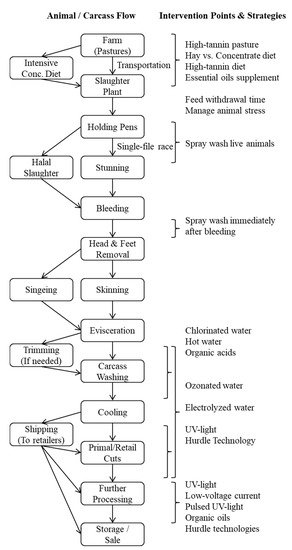

Dietary manipulation, feed deprivation duration prior to slaughter, supplementation with high tannin-containing diets, minimizing animal stress, and live animal washing have been studied as possible pre-harvest intervention strategies to reduce E. coli in goats. Research on postharvest methods in goats have included treating goat meat with ozonated water, electrolyzed oxidizing water, ultraviolet light, sonication, organic acids, and organic oils, to name a few. In addition, nonthermal hurdle technologies with different treatment-time combinations have also been found to be promising.

2. Prevalence of E. coli in Goats

Several countries from different continents have reported

E. coli O157:H7 in humans. Although this organism has been isolated from several animal species, ruminant livestock species are regarded as natural carriers of

E. coli. These food animals typically do not show any clinical signs while shedding

E. coli through feces. Isolation of

E. coli O157:H7 from goats was first reported in 1994 from a human outbreak of

E. coli O157:H7 in United Kingdom [

4].

Researchers have reported different prevalence rates in different countries. According to Dulo et al. [

5],

E. coli O157:H7 was present in 2.2% of cecal content samples and 3.2% of carcass swab samples obtained from goats in Somali region of Ethiopia. The researchers suggested that poor hygiene and slaughter practices may cause contamination of meat and human health risks as consumption of raw meat is a common practice in Ethiopia. A comparison of

E. coli O157:H7 contamination rate among beef, lamb, and chevon samples from slaughter plants and retail outlets in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, showed that beef was the most frequently contaminated meat, followed by sheep and goat meat [

6]. This study also revealed that contamination rates were higher at retail shops than at slaughterhouses for beef (21.9 vs. 4.7%), sheep (10.9 vs. 6.3%), and goat (9.4 vs. 6.3%) carcass and meat samples. Sixty percent of goat meat samples collected from different markets in Dhaka, Bangladesh has been reported to be positive for

E. coli O157:H7 strains, although no official infections have been reported either due to improper tracking of outbreaks and causative organisms or to possible acquired immunity in the population [

7]. Another report from Bangladesh also showed that prevalence of multidrug-resistant

E. coli was higher in younger goats than older goats. The authors also reported that the prevalence of drug-resistant

E. coli was higher in goats raised in poor hygienic conditions than those raised in good hygienic conditions, and higher in goats with recent history of transportation [

8]. Shiga toxin-producing

E. coli prevalence in Jordan was found to be greater in intensively reared goats with occasional grazing (65%) than in extensively reared goats with year-round grazing (50%) [

9].

Preharvest meat goat management, slaughter and processing, and postharvest carcass and meat handling methods vary among different countries and regions. The

E. coli counts on goat skin prior to slaughter generally range from 2.2 to 2.5 log

10 CFU cm

−2, and those on carcasses before washing range from 2.1 to 2.3 log10 CFU cm

−2 [

10,

11]. It is not clear to what extent factors such as sex, age, and breed can influence

E. coli shedding in goats. A generic flow diagram of various steps involved in pre- and post-harvest phases of chevon production is included to illustrate potential intervention points (

Figure 1).

Figure 1. A generic flow diagram of various steps involved in pre- and post-harvest phases of goat meat production to illustrate potential intervention points [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ani11102943