Oxidative stress mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays a key role in the atherosclerotic process. ROS not only oxidize LDL, they also promote several pro-atherogenic effects, including inflammation, apoptosis, and alteration of vascular tone. The imbalance between pro- and antioxidant agents drives to the formation and progression of atherosclerotic plaque lesions. In this sense, the transcription factor Nuclear factor–erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is known to activate the expression of more than 250 antioxidant enzymes—such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), glutathione peroxidase, or glutamate-cysteine ligase —making it a master regulator of oxidative stress. Nrf2 has been associated with different cardiovascular-related pathologies—such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, hypertension, or heart failure. Currently, Nrf2 signaling pathway is considered an important defense mechanism against cardiovascular diseases (CVDs).

- atherosclerosis

- oxidative stress

- heme oxygenase-1

- Nrf2

1. Atherosclerosis and Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is highly involved in the initiation and development of atherosclerosis [1]. Apart from the active oxygen compounds, free radicals (O2.₋, .OH) and non-free radicals (H2O2, ½ O2), reactive nitrogen, copper, iron and sulfur species are also considered as oxidative stress related molecules, since they promote or participate through different mechanisms in the synthesis of ROS [2][1]. ROS production increases in response to many risk factors associated with atherosclerotic CVDs—such as hypertension, diabetes, smoking, or dyslipidemia [1]. Similarly, oxidative stress can result from the imbalance of oxidant and antioxidant agents, promoting cell toxicity related to atherosclerosis [3]. Under physiological conditions, antioxidants help to prevent damage from free radicals and other oxidant molecules without affecting redox reactions that are fundamental for appropriate cell function [4]. However, under pathological situations, an imbalance of oxidant (enhanced) versus antioxidant enzymes (reduced) leads to oxidative stress (Figure 1). Then, many different processes can take place, including NO inactivation; oxidation of lipids, proteins, or even DNA; cell apoptosis; or enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and ox-LDL receptors (CD36, LOX-1) [5][6]. Remarkably, ROS promotes the expression of SR in VSMCs, ox-LDL recognition and uptake, as well as their transformation into foam cells [1]. In the same way, ROS can activate the release of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which could degrade the basement membrane and atheroma plaque structure, disrupting it. Additionally, ECs and SMCs can generate different oxidant agents through several enzymes [7].

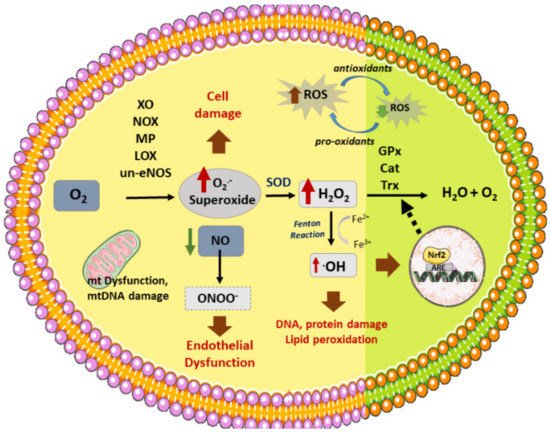

Figure 1. Vascular sources of ROS and related enzymes. Different enzymes participate in the formation of ROS: NOX (NADPH oxidase), XO (xanthine oxidase), un-eNOS (uncoupled nitric oxide synthase), LOX (lipoxygenase), MP (myeloperoxidase), generating superoxide (O2.-) from O2. In addition, dysfunctional mitochondrial (mt) respiratory chain is another source of (O2.₋). On the other hand, SOD (superoxide dismutase) produces H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) from superoxide, which can then be converted to H2O by several antioxidant enzymes: GPx (glutathione peroxidase), Cat (catalase), or Trx (Thyoredoxin). H2O2 reacts with transition metals such as Fe2+ (through the Fenton reaction) to produce hydroxyl radicals (.OH). Nitric oxide (NO) reacts with O2.₋ to produce peroxynitrite (ONOO₋). ROS stimulates Nrf2 activation and translocation to the nucleus, activating the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes. ROS production induces cell death, DNA and lipid peroxidation, and endothelial dysfunction, among other effects, which triggers the atherosclerotic process.

2. NRF2 Antioxidant Roles in Atherosclerosis

Nrf2, encoded by NFE2L2 gene, constitutes a transcription factor that has been closely linked to atherosclerosis, although its specific role in this pathology is not clear. Nrf2 might play antagonistic roles, both preventing and enhancing atherosclerotic development [8][9][10]. For instance, several studies related to laminar and oscillatory blood flow have revealed that the former stimulates the antiatherogenic activation of Nrf2, while the latter promotes the opposite effect [11]. Studies with ApoE₋/₋ and Nrf2₋/₋ or Nrf2+/₋ mice indicate a reduction of the atherosclerotic process in these animals, suggesting a deleterious role of the transcription factor [8][12]. Nrf2 expression in ApoE Knockout mice seems to accelerate the late stages—but not the early stages—of atherosclerosis [13], while in absence of macrophage Nrf2, both atherosclerotic stages are affected in LDLR KO mice [9]. Nrf2 might potentiate atherosclerosis through different pathways, as described [14], promoting among others the formation of foam cells [15] or the monocyte recruitment to the lesion areas by upregulation of IL-1α in macrophages [8]. Nrf2 modulates the expression of CD36 scavenger receptor in macrophages, responsible for ox-LDL uptake and accumulation and subsequent formation of foam cells [16]. In this regard, controversial results have been assigned to the Nrf2/CD36 pathway in atherosclerosis, with studies indicating reduced ox-LDL accumulation in Nrf2 KO macrophages and decreased CD36 levels in atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE₋/₋ Nrf2₋/₋ mice [13][16]. Conversely, lack of Nrf2 in peritoneal macrophages seems to increase modified LDL uptake, suggesting that CD36 is not the only factor responsible for ox-LDL accumulation [9][16].

The majority of studies, however, have focused on the athero-protective properties of Nrf2, mainly as a key agent against oxidative stress [17]. Apart from being able to activate the expression of many antioxidant enzymes, Nrf2 has the potential to modulate NADPH oxidase activity as well. Thus, the levels of pro-atherogenic Nox2 appear to increase significantly in absence of Nrf2, whereas Nox4 is upregulated when Nrf2 is constitutively activated [18][19]. Interestingly, ROS produced by NADPH oxidase can also activate Nrf2, at least in cardiomyocites and pulmonary epithelial cells [20]. Such activation may represent an endogenous protecting mechanism against mitochondrial damage and cell death in the heart during chronic pressure overload [21]. Studies with Nrf2-KO mouse glio-neuronal cells have shown higher rates of mitochondrial ROS production in these cells than in wild type Nrf2 cells, suggesting a modulatory role for Nrf2 over the mitochondrial respiratory chain [18]. Indeed, Nrf2 enhances mitochondrial biogenesis, as well as the activation of OxPhos, among others. Finally, mitochondrial ROS also stimulates Nrf2 activation, thus representing a continuous regulatory loop [18][22].

Nrf2 not only protects against oxidative stress in ECs through activation of different antioxidant genes, it also exerts anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects on these cells [23]. Indeed, Nrf2 suppresses the expression of VCAM-1 and TNFα—induced expression of MCP-1 in HUVECs [24] and HAECs [25]. Likewise, endothelial Nrf2 antioxidant response can be activated in areas exposed to oscillatory shear stress, exerting an athero-protective role [26]. Similarly, Nrf2 reduces the inflammatory response in macrophages and foam cells by modulation of several inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 or TNFα [9]. Finally, Nrf2 could protect VSMCs against oxidative stress, and may protect against atherosclerosis progression by activation of athero-protective genes, such as HO-1 or NAD(P)H dehydrogenase quinone 1 (NQO1), which suppress proliferation of SMCs and VSMCs respectively [27][28].

Modulation of Nrf2 Activity

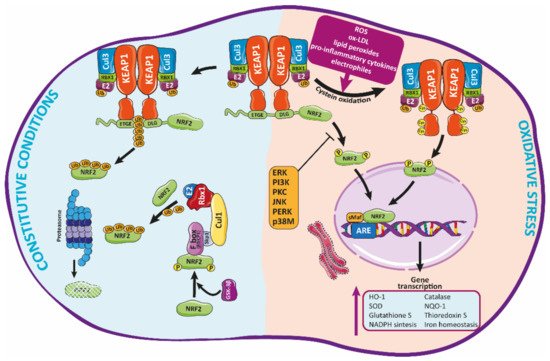

Nrf2 belongs to “Cap’n’Collar” (CNC) family of transcription factors with a b-ZIP domain [29][30] which modulate the cellular redox status [29]. Nrf2 has seven domains that regulate the stability and functional activity of this factor [31]. Under normal homeostatic conditions, Nrf2 is trapped in the cytosol, associated with the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 (KEAP-1) through the N-terminal (Neh2 domain) [31] (Figure 2). Keap1 acts as an endogenous inhibitor of Nrf2 [32]. In fact, Keap1 is the major regulator of Nrf2 activity [33], through the aforementioned interaction with Nrf2, which promotes the assembling with the Cullin3 (Cul3)/Rbx1 (Ring box-1)-based E3-ubiquitin ligase complex that targets Nrf2 for constant proteasomal degradation [31]. This complex keeps Nrf2 in the cytosol, avoiding its translocation to the nucleus and the transcription of antioxidant related genes [33].

Figure 2. Regulation of Nrf2 signaling and HO-1 expression. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is trapped into the cytosol associated with the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 (KEAP-1) through the N-terminal (Neh2 domain). Herein, Nrf2 is transferred to proteasomal degradation after being ubi-quinylated. In response to pathological agents such as ROS, Nrf2 is released from this complex after oxidation of Keap1 cysteine residues, moving toward the nucleus, where it binds to ARE regions, inducing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as HO-1.

Many factors—such as ROS, ox-LDL, lipid peroxides and their metabolites, electrophiles, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and many other molecules related to oxidative stress—can induce an alteration of Keap1 conformation (by modification of its cysteines residues) [34][15], promoting the release of Nrf2 which then translocates to the nucleus [15]. Herein, Nrf2 binds through the Neh1 functional domain to small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (sMaf) proteins, forming heterodimers with them [35]. Such dimerization allows Nrf2 to interact with the DNA through the antioxidant response element (ARE) sequence in specific gene regulatory regions [31]. Through this mechanism, Nrf2 modulates the expression of many genes encoding different antioxidant proteins—e.g., HO-1, catalase, SOD, or NQO-1 [36] among others—which will contribute to reduce cellular oxidative stress [15][37]. Likewise, Nrf2 regulates the glutathione and thioredoxin systems, NADPH production and utilization, and iron homeostasis. Many of these antioxidant factors actively participate in the detoxification and elimination of pro-oxidant compounds [36].

Currently, the Nrf2/Keap1 system is considered the principal mechanism against o-xidative stress, which is widely conserved, mainly in mammals [38]. This system is mainly modulated, as indicated above, by the interaction of diverse substances with several cysteines residues present in Keap1. Indeed, Keap1 contains more than 27 cysteine residues that have been described as potentially involved in the modulation of this protein and its interaction with Nrf2 [39]. Among them, Cys151 promotes Nrf2 release and activation, while Cys273, 288, and 297 facilitate the interaction of Keap1 with Nrf2, therefore inactivating this protein [40]. The current model postulates that, in response to different stimuli, modification of Keap1 thiols promotes conformational changes that negatively affect the ubiquitin ligase activity of the Keap1-Cul3 complex, as described before, releasing Nrf2 which then translocates to the nucleus and activates the synthesis of antioxidant genes [33]. Alternatively, the “hinge and latch” model suggests that, in response to stimuli, Nrf2 is synthesized de novo, instead of being released from Keap1, accumulating as well in the nucleus [41].

The Nrf2/Keap1 system can also be regulated by the autophagy regulator protein p62 (Sequestosome1, SQSTM1). Phosphorylation of p62 in response to many factors such as oxidative stress [42] allows the direct binging of this protein to Keap1, promoting its degradation by autophagia, and subsequent displacement and activation of Nrf2 [43]. Remarkably, p62 expression is also induced by Nrf2 in response to ROS [44]. Thus, the p62/Nrf2 route might represent an attractive candidate to promote Nrf2 activation and antioxidant response. However, given the strong correlation found between p62 upregulation and activation of Nrf2 pathway with several cancer types, major efforts have been made mainly toward the identification of potential pharmacological inhibitors of this p62/Nrf2 pathway [45].

Apart from Keap1, other molecules can regulate Nrf2 activity through additional control points at transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational level [34][46] (Table 1). Several kinases, such as glycogen synthase kinase-3-beta (GSK3β), have been described as modulators of Nrf2 activity [47]. Nrf2 phosphorylation by GSK-3β activates the recognition and binding of Nrf2 to β-transducin repeat-containing protein (β-TrCP), an adaptor for the Skp1-Cul1-Rbx1-F-box protein (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Similarly to the Nrf2-Keap1-Cul3 complex, this complex promotes Nrf2 ubiquitination and further proteasomal degradation [48][49]. Other kinases—such as protein kinase-C (PKC), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), PERK, p38 MAPK, JNK, and PI3K—can also influence Nrf2 activity [10][50][51]. Remarkably, while phosphorylation of certain residues of Nrf2 (Ser40, Ser558) by kinases like PKC or AMPK-mediated phosphorylation enhance nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and transcription of antioxidant enzymes [50][51], phosphorylation or other residues (Tyr576, Ser44, Ser347) by enzymes such as Fyn kinase or GSK3B, can promote Nrf2 to be exported from the nucleus to the cytosol, which activates its proteasomal degradation [48].

Table 1. Modulators of Nrf2. Protein kinases and miRNA known to regulate Nrf2 activity are shown. Acronyms: GSK-3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3β; FYN: Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Fyn; p38: p38 MAP kinase; PI3K/Akt: Phopshoinositide 3-kinase/Protein kinase B (Akt); PKC: Protein kinase C; JNK: c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; PERK: Protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; miRNA: micro RNA.

| Protein Kinases | Identified in | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSK-3β | HEK293T | Inhibits NRF2 | [48] Rada et al., 2011 [52] Salazar et al., 2006 |

| HepG2 | Inhibits NRF2 | [53] Jain et al., 2006 | |

| FYN | HepG2 | Inhibits NRF2, via GSK-3B | [47] Jain et al., 2007 |

| P38 MAP kinase | Thymocytes and 293T; HepG2 | Inhibits HO-1/Nrf2 Activates HO-1/Nrf2 |

[54] Thornton et al., 2008; [55] Shen et al., 2004 [56] Elbirt et al. 1998 |

| PI3k /Akt | 293T | Activates NRF2, by Gsk-3β inhibition. | [52] Salazar M et al. 2006 |

| PKC | HepG2 | Activates NRF2 | [50] Huang et al., 2002 |

| JNK | HepG2 | Activates NRF2 | [55] Shen et al., 2004 |

| ERK | HepG2 | Activates NRF2, through GSK-3β inhibition. | [55] Shen et al., 2004 [56] Elbirt et al., 1998 |

| PERK | Mouse embryonic fibroblasts | Activates NRF2 | [57] Cullinan et al. 2003 |

| AMPK | HepG2, HEK293 | Activates Nrf2 | [51] Joo et al. 2016 |

| miRNA | Identified in | Effect | References |

| miR-28 | Breast cancer cell lines | Inhibits | [58] Yang et al., 2011 |

| miR-34a | Hepatocytes | Inhibits | [59] Huang et al., 2014 |

| Cardiomyocytes | [60] Wang et al., 2019 | ||

| miR-132, miR-200c | Renal proximal tubular cell line | Inhibits | [61] Stachurska et al., 2012 |

| miR-144 | Neuronal cell lines; Lymphoblast cell lines (k562 cell line) |

Inhibits | [62] Zhou et al., 2017 |

| miR-153, miR27a, miR-142-5p | Neuronal cell lines | Inhibits | [63] Narashimhan et al., 2012 |

| miR-200a | OB-6 osteoblastic cells | Increases | [64] Zhao et al., 2017 |

| miR-140-5p | HK2 cells | Increases NRF2 expression | [65] Liao W et al., 2017 |

| miR873-5p | Mouse renal tubular epithelial cells (mRTECs) | Increases NRF2 and HO-1 expression | [66] Wang J et al., 2019 |

Alternatively, several studies suggest that different microRNAs (miRNAs) (i.e., miR-27a, miRNA-28a or -34a) can also regulate, directly or indirectly, Nrf2 expression and moreover, to control the antioxidant activity of the Keap1-Nrf2 complex and Nrf2/ARE signaling pathways [46][67]. miRNAs are small noncoding molecules that bind to specific regions of mRNA (UTRs), promoting either their degradation or blocking their translation, reducing their levels. Thus, several miRNAs—such as miR-28, miR-507, mi-450a or miR-634—have been found to inhibit Nrf2 expression in studies involving cancer cells [45]. Another study found that downregulation of miRNA-93 increases Nrf2 expression, reducing ROS and cell apoptosis and diabetic retinopathy [68]. Additionally, miRNA-153 promoted oxidative stress by inhibiting Nrf2 activity in an in vitro model of Parkinson´s disease [69]. As concerning Keap1, miR-141 was the first miRNA identified to suppress Keap1 levels in ovarian cancer cell lines [70]. Similarly, miR-432-3p was found to impair Keap1 mRNA translation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, positively modulating Nrf2 activity [71], while increased levels of miR-200a promoted Keap1 degradation and Nrf2 stabilization in OB-6 osteoblastic cells [64]. Overall, there is a growing number of studies supporting the potential use of miRNAs as an strategy to modulate the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway, either inhibiting (as it happens in cancer) or promoting the activation of Nrf2 as an antioxidant approach. Future research could benefit from these findings.

3. HO-1 Antioxidant Role in Atherosclerosis

HO-1 has many important roles that contribute to the protection against atherosclerosis, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiapoptotic, or immunomodulatory effects [14]. HO-1 is expressed in the main cell types detected in human and mouse athe-rosclerotic lesions, including EC, macrophages, or SMCs [14][72].

HO-1 is a highly conserved enzyme—also known as 32-kDa heat shock protein—encoded by the hmox1 gene [73][74]. There are currently three isoforms of HO: HO-1, HO-2, and HO-3, although the last one seems to derive from HO-2 transcripts [75]. While HO-2 is constitutively expressed, HO-1 is usually present at low levels in many tissues but it can be stimulated by many factors [14]. For instance, HO-1 expression can be enhanced in response to ROS, ischemia-reperfusion, carcinogenesis, atherosclerosis itself, or other inflammatory processes [76]. Moreover, different transcriptor factors such as Nrf2, activator protein-1 (AP-1), or nuclear factor-kappa B (NFκB) have been shown to activate HO-1 expression, together with several up-stream kinases, like protein kinases A and C or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [76][77].

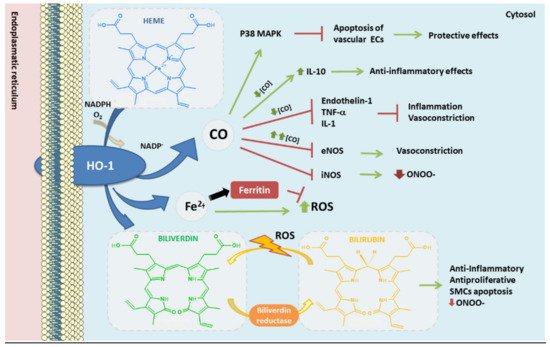

In mammals, heme oxygenase enzymes are located on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum, anchored to it by hydrophobic amino acids at its COOH-terminal ends. Its ca-talytic part contains a “heme binding pocket” of 24 amino acids, oriented to the cytosol [78][74], together with a histidine-imidazole residue where it binds to the heme iron [78]. HO-1 enzymatically catalyzes the oxidative cleavage of the heme group (mainly heme b) of metalloproteins in equimolar amounts of carbon monoxide (CO), Fe2+ and biliverdin IXα [78] (Figure 3). Biliverdin is then converted to bilirubin by the cytosolic biliverdin reductase (BVR). All these three products have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiapoptotic, antithrombotic, and antiproliferative functions in vascular cells [14][79]. Thus, the anti-atherogenic role assigned to HO-1 appears to be associated, among others, with the bioproducts, biliverdin, bilirubin, and the vasodilator CO, providing arterial protection against oxidant-induced injury [79].

Figure 3. Heme oxygenase-1 antioxidant products derived from heme degradation. Heme oxyge-nase-1 (HO-1) catabolizes heme degradation into equimolar amounts of carbon monoxide (CO), Fe2+ and biliverdin. Biliverdin is converted to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase (BVR). All these products have shown antioxidant, anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory properties. In addition, HO-1 induces the production of ferritin, an iron storing protein—reducing the levels of Fe2+ which could derive into ROS via Fenton reaction.

Different cell-based and in vivo research studies have demonstrated that HO-1 upregulation protects vascular walls from endothelial dysfunction and pathological remodeling, significantly inhibiting the atherosclerotic process [79][80][81][82][83]. Besides, diverse genetic population studies have indicated the importance of HO-1 expression as a protecting phenomenon against atherosclerosis [14]. Under basal conditions HO-1 is under-expressed in most tissues, however when a vascular injury occurs, the expression is higher [79]. High blood HO-1 levels have been found in different chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus [84] or Parkinson´s disease [85][86], mainly released into the plasma by different cell types in response to inflammation or oxidative stress [87]. Remarkably, the expression of HO-1 arising from macrophages during oxidative conditions was found higher in coronary artery disease (CAD) patients when compared to healthy subjects [88]. Likewise, HO-1 plasma levels are higher in patients with carotid plaques compared to those without plaques, and these levels increase with the severity of the plaques [89]. HO-1 expression is high in atherosclerotic lesions, correlating with plaque instability and pro-inflammatory markers [73]. However, such upregulation enhances the stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques, therefore representing an athero-protective mechanism [79][90]. Similarly, increased levels of bilirubin in plasma have been associated with lower incidence of CVDs [91] while low levels of bilirubin correlate with endothelial dysfunction and increased intima-media thickness [73][92], being inversely correlated the levels of bilirubin in serum with the severity of atherosclerosis in men [93]. Such anti--atherogenic role relies mainly on the antioxidant properties of bilirubin/biliverdin. Bilirubin seems capable to scavenge oxygen radicals and inhibit oxidation of LDL and other lipids, as well as presenting anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative roles [14]. For instance, bilirubin enhances SMCs apoptosis, preventing its accumulation in vascular walls, and it blocks the recruitment and infiltration of leukocytes into these walls [94]. Finally, bilirubin cytoprotective action might be related to its capacity to inhibit inducible NOS (iNOS), reducing the production of the free radical ONOO- [95].

In the same way, CO inhibits apoptosis in vascular ECs by activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [96]. Besides, CO blocks LPS-derived upregulation of iNOS and therefore an overproduction of NO in macrophages [97], modulating the response of these cells against bacterial LPS [98]. At low concentrations, CO inhibits vasoconstrictor enzymes, such as endothelin-1, as well as the production of TNFα and IL-1 (pro-inflammatory interleukin) and increases IL-10 (anti-inflammatory interleukin) [99]; while at high concentrations it has a vasoconstriction effect, inhibiting the action of eNOS. Among other properties of CO, the antioxidant role of this molecule might be due to its capability to bind Fe2+ in the heme group, preventing oxidation of hemoproteins, and avoiding the release of free heme [14][100].

The heme molecule itself is fundamental for many biological functions, due to its role as prosthetic group in hemoproteins like Hemoglobin (Hb), a major transporter of O2. However, free heme can be toxic for several reasons [101]. For instance, heme can affect vascular ECs integrity by oxidation of LDL [73][102], and it can enhance cellular cytotoxicity through different sources of ROS [103]. Moreover, free heme increases the chances of releasing Fe2+ from its porphyrin pocket [101], which can be oxidized to Fe3+ through the Fenton reaction, an important source of ROS. Fe3+ can promote LDL oxidation in presence of superoxide anion (O2.₋) [73]. Moreover, excessive amounts of iron can also modulate the activity of several enzymes directly involved in regulating cholesterol and triglyceride levels, which could have a negative effect over lipid metabolism [104]. For instance, different studies have demonstrated the correlation between iron overload and endothelial dysfunction, suggesting a critical role of redox active iron in the proinflammatory res-ponse of ECs [105]. Notably, elevated concentrations of iron can be found in atherosclerotic lesions compared to non-atherosclerotic vessels [78]. Therefore, the presence of redox active iron in atherosclerotic plaques may enhance the progression of atherosclerotic lesions by promoting an increase of free radicals, lipid peroxidation, and endothelial dysfunction.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox10091463

References

- Kattoor, A.J.; Pothineni, N.V.K.; Palagiri, D.; Mehta, J.L. Oxidative Stress in Atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017, 19, 42.

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, D.; Gao, Y.; Xing, Y.; Shang, H. Oxidative Stress-Mediated Atherosclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapies. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 600.

- Marchio, P.; Guerra-Ojeda, S.; Vila, J.M.; Aldasoro, M.; Victor, V.M.; Mauricio, M.D. Targeting Early Atherosclerosis: A Focus on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 8563845.

- Tousoulis, D.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Androulakis, E.; Papageorgiou, N.; Papaioannou, S.; Oikonomou, E.; Synetos, A.; Stefanadis, C. Oxidative stress and early atherosclerosis: Novel antioxidant treatment. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2015, 29, 75–88.

- Chen, M.; Masaki, T.; Sawamura, T. LOX-1, the receptor for oxidized low-density lipoprotein identified from endothelial cells: Implications in endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 95, 89–100.

- Nicholson, A.C.; Han, J.; Febbraio, M.; Silversterin, R.L.; Hajjar, D.P. Role of CD36, the macrophage class B scavenger receptor, in atherosclerosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 947, 224–228.

- Wassmann, S.; Wassmann, K.; Nickenig, G. Modulation of oxidant and antioxidant enzyme expression and function in vascular cells. Hypertension 2004, 44, 381–386.

- Freigang, S.; Ampenberger, F.; Spohn, G.; Heer, S.; Shamshiev, A.T.; Kisielow, J.; Hersberger, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Bachmann, M.F.; Kopf, M. Nrf2 is essential for cholesterol crystal-induced inflammasome activation and exacerbation of atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 2040–2051.

- Ruotsalainen, A.K.; Inkala, M.; Partanen, M.E.; Lappalainen, J.P.; Kansanen, E.; Makinen, P.I.; Heinonen, S.E.; Laitinen, H.M.; Heikkila, J.; Vatanen, T.; et al. The absence of macrophage Nrf2 promotes early atherogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 98, 107–115.

- Mimura, J.; Itoh, K. Role of Nrf2 in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 221–232.

- Hosoya, T.; Maruyama, A.; Kang, M.I.; Kawatani, Y.; Shibata, T.; Uchida, K.; Warabi, E.; Noguchi, N.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M. Differential responses of the Nrf2-Keap1 system to laminar and oscillatory shear stresses in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 27244–27250.

- Sussan, T.E.; Jun, J.; Thimmulappa, R.; Bedja, D.; Antero, M.; Gabrielson, K.L.; Polotsky, V.Y.; Biswal, S. Disruption of Nrf2, a key inducer of antioxidant defenses, attenuates ApoE-mediated atherosclerosis in mice. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3791.

- Harada, N.; Ito, K.; Hosoya, T.; Mimura, J.; Maruyama, A.; Noguchi, N.; Yagami, K.; Morito, N.; Takahashi, S.; Maher, J.M.; et al. Nrf2 in bone marrow-derived cells positively contributes to the advanced stage of atherosclerotic plaque formation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 2256–2262.

- Araujo, J.A.; Zhang, M.; Yin, F. Heme oxygenase-1, oxidation, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2012, 3, 119.

- Ooi, B.K.; Goh, B.H.; Yap, W.H. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Involvement of Nrf2 Antioxidant Redox Signaling in Macrophage Foam Cells Formation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2336.

- Ishii, T.; Itoh, K.; Ruiz, E.; Leake, D.S.; Unoki, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Mann, G.E. Role of Nrf2 in the regulation of CD36 and stress protein expression in murine macrophages: Activation by oxidatively modified LDL and 4-hydroxynonenal. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 609–616.

- Howden, R. Nrf2 and cardiovascular defense. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 104308.

- Kovac, S.; Angelova, P.R.; Holmstrom, K.M.; Zhang, Y.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abramov, A.Y. Nrf2 regulates ROS production by mitochondria and NADPH oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 794–801.

- Brewer, A.C.; Murray, T.V.; Arno, M.; Zhang, M.; Anilkumar, N.P.; Mann, G.E.; Shah, A.M. Nox4 regulates Nrf2 and glutathione redox in cardiomyocytes in vivo. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 205–215.

- Papaiahgari, S.; Kleeberger, S.R.; Cho, H.Y.; Kalvakolanu, D.V.; Reddy, S.P. NADPH oxidase and ERK signaling regulates hyperoxia-induced Nrf2-ARE transcriptional response in pulmonary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 42302–42312.

- Smyrnias, I.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Murray, T.V.; Brandes, R.P.; Schroder, K.; Brewer, A.C.; Shah, A.M. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-4-dependent upregulation of nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 protects the heart during chronic pressure overload. Hypertension 2015, 65, 547–553.

- Kasai, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tatara, Y.; Mimura, J.; Itoh, K. Regulation of Nrf2 by Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Physiology and Pathology. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 320.

- Chen, X.L.; Dodd, G.; Thomas, S.; Zhang, X.; Wasserman, M.A.; Rovin, B.H.; Kunsch, C. Activation of Nrf2/ARE pathway protects endothelial cells from oxidant injury and inhibits inflammatory gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H1862–H1870.

- Pae, H.O.; Oh, G.S.; Lee, B.S.; Rim, J.S.; Kim, Y.M.; Chung, H.T. 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid, one of L-tryptophan metabolites, inhibits monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 secretion and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression via heme oxygenase-1 induction in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2006, 187, 274–284.

- Chen, X.L.; Dodd, G.; Kunsch, C. Sulforaphane inhibits TNF-alpha-induced activation of p38 MAP kinase and VCAM-1 and MCP-1 expression in endothelial cells. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 513–521.

- Dai, G.; Vaughn, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, E.T.; Garcia-Cardena, G.; Gimbrone, M.A., Jr. Biomechanical forces in atherosclerosis-resistant vascular regions regulate endothelial redox balance via phosphoinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent activation of Nrf2. Circ. Res. 2007, 101, 723–733.

- Kim, S.Y.; Jeoung, N.H.; Oh, C.J.; Choi, Y.K.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Hwang, J.H.; Tadi, S.; Yim, Y.H.; et al. Activation of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 prevents arterial restenosis by suppressing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 842–850.

- Cheng, C.; Haasdijk, R.A.; Tempel, D.; den Dekker, W.K.; Chrifi, I.; Blonden, L.A.; van de Kamp, E.H.; de Boer, M.; Burgisser, P.E.; Noorderloos, A.; et al. PDGF-induced migration of vascular smooth muscle cells is inhibited by heme oxygenase-1 via VEGFR2 upregulation and subsequent assembly of inactive VEGFR2/PDGFRbeta heterodimers. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 1289–1298.

- Sykiotis, G.P.; Bohmann, D. Stress-activated cap’n’collar transcription factors in aging and human disease. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, re3.

- Moi, P.; Chan, K.; Asunis, I.; Cao, A.; Kan, Y.W. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 9926–9930.

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell. Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733.

- Canning, P.; Sorrell, F.J.; Bullock, A.N. Structural basis of Keap1 interactions with Nrf2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 101–107.

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139.

- Guerrero-Hue, M.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Vazquez-Carballo, C.; Palomino-Antolin, A.; Garcia-Caballero, C.; Opazo-Rios, L.; Morgado-Pascual, J.L.; Herencia, C.; Mas, S.; Ortiz, A.; et al. Protective Role of Nrf2 in Renal Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 39.

- Cuadrado, A.; Rojo, A.I.; Wells, G.; Hayes, J.D.; Cousin, S.P.; Rumsey, W.L.; Attucks, O.C.; Franklin, S.; Levonen, A.L.; Kensler, T.W.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of the NRF2 and KEAP1 partnership in chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 295–317.

- Nguyen, T.; Nioi, P.; Pickett, C.B. The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 13291–13295.

- Bryan, H.K.; Olayanju, A.; Goldring, C.E.; Park, B.K. The Nrf2 cell defence pathway: Keap1-dependent and -independent mechanisms of regulation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 85, 705–717.

- Yuji Fuse, M.K. Conservation of the Keap1-Nrf2 System: An Evolutionary Journey through Stressful Space and Time. Molecules 2017, 22, 436.

- Holland, R.; Hawkins, A.E.; Eggler, A.L.; Mesecar, A.D.; Fabris, D.; Fishbein, J.C. Prospective type 1 and type 2 disulfides of Keap1 protein. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 2051–2060.

- He, X.; Ma, Q. Critical cysteine residues of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 in arsenic sensing and suppression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 332, 66–75.

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.I.; Watai, Y.; Tong, K.I.; Shibata, T.; Uchida, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative and electrophilic stresses activate Nrf2 through inhibition of ubiquitination activity of Keap1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 221–229.

- Jain, A.; Lamark, T.; Sjottem, E.; Larsen, K.B.; Awuh, J.A.; Overvatn, A.; McMahon, M.; Hayes, J.D.; Johansen, T. p62/SQSTM1 is a target gene for transcription factor NRF2 and creates a positive feedback loop by inducing antioxidant response element-driven gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22576–22591.

- Komatsu, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Waguri, S.; Taguchi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ichimura, Y.; Sou, Y.S.; Ueno, I.; Sakamoto, A.; Tong, K.I.; et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2010, 12, 213–223.

- Ishii, T.; Itoh, K.; Takahashi, S.; Sato, H.; Yanagawa, T.; Katoh, Y.; Bannai, S.; Yamamoto, M. Transcription factor Nrf2 coordinately regulates a group of oxidative stress-inducible genes in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 16023–16029.

- Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Potential Applications of NRF2 Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8592348.

- Tian, C.; Gao, L.; Zucker, I.H. Regulation of Nrf2 signaling pathway in heart failure: Role of extracellular vesicles and non-coding RNAs. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 167, 218–231.

- Jain, A.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. GSK-3beta acts upstream of Fyn kinase in regulation of nuclear export and degradation of NF-E2 related factor 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 16502–16510.

- Rada, P.; Rojo, A.I.; Evrard-Todeschi, N.; Innamorato, N.G.; Cotte, A.; Jaworski, T.; Tobon-Velasco, J.C.; Devijver, H.; Garcia-Mayoral, M.F.; Van Leuven, F.; et al. Structural and functional characterization of Nrf2 degradation by the glycogen synthase kinase 3/beta-TrCP axis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 3486–3499.

- Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, Y.; McMahon, M.; Sutherland, C.; Cuadrado, A.; Hayes, J.D. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct beta-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene 2013, 32, 3765–3781.

- Huang, H.C.; Nguyen, T.; Pickett, C.B. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 at Ser-40 by protein kinase C regulates antioxidant response element-mediated transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 42769–42774.

- Joo, M.S.; Kim, W.D.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Koo, J.H.; Kim, S.G. AMPK Facilitates Nuclear Accumulation of Nrf2 by Phosphorylating at Serine 550. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 36, 1931–1942.

- Salazar, M.; Rojo, A.I.; Velasco, D.; de Sagarra, R.M.; Cuadrado, A. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits the xenobiotic and antioxidant cell response by direct phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 14841–14851.

- Jain, A.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. Phosphorylation of tyrosine 568 controls nuclear export of Nrf2. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 12132–12142.

- Thornton, T.M.; Pedraza-Alva, G.; Deng, B.; Wood, C.D.; Aronshtam, A.; Clements, J.L.; Sabio, G.; Davis, R.J.; Matthews, D.E.; Doble, B.; et al. Phosphorylation by p38 MAPK as an alternative pathway for GSK3beta inactivation. Science 2008, 320, 667–670.

- Shen, G.; Hebbar, V.; Nair, S.; Xu, C.; Li, W.; Lin, W.; Keum, Y.S.; Han, J.; Gallo, M.A.; Kong, A.N. Regulation of Nrf2 transactivation domain activity. The differential effects of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and synergistic stimulatory effect of Raf and CREB-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 23052–23060.

- Elbirt, K.K.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Davis, R.J.; Bonkovsky, H.L. Mechanism of sodium arsenite-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1 in hepatoma cells. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 8922–8931.

- Cullinan, S.B.; Zhang, D.; Hannink, M.; Arvisais, E.; Kaufman, R.J.; Diehl, J.A. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 7198–7209.

- Yang, M.; Yao, Y.; Eades, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q. MiR-28 regulates Nrf2 expression through a Keap1-independent mechanism. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 129, 983–991.

- Huang, X.; Gao, Y.; Qin, J.; Lu, S. The role of miR-34a in the hepatoprotective effect of hydrogen sulfide on ischemia/reperfusion injury in young and old rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113305.

- Wang, X.; Yuan, B.; Cheng, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Yang, B.; Gong, G. Crocin Alleviates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress via Regulation of miR-34a/Sirt1/Nrf2 Pathway. Shock 2019, 51, 123–130.

- Stachurska, A.; Ciesla, M.; Kozakowska, M.; Wolffram, S.; Boesch-Saadatmandi, C.; Rimbach, G.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J.; Loboda, A. Cross-talk between microRNAs, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2, and heme oxygenase-1 in ochratoxin A-induced toxic effects in renal proximal tubular epithelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 504–515.

- Zhou, C.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, K.; Deng, H.; Liu, P.; Chen, L.; Mu, H. MicroRNA-144 modulates oxidative stress tolerance in SH-SY5Y cells by regulating nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2-glutathione axis. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 655, 21–27.

- Narasimhan, M.; Patel, D.; Vedpathak, D.; Rathinam, M.; Henderson, G.; Mahimainathan, L. Identification of novel microRNAs in post-transcriptional control of Nrf2 expression and redox homeostasis in neuronal, SH-SY5Y cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51111.

- Zhao, S.; Mao, L.; Wang, S.G.; Chen, F.L.; Ji, F.; Fei, H.D. MicroRNA-200a activates Nrf2 signaling to protect osteoblasts from dexamethasone. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 104867–104876.

- Liao, W.; Fu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Wen, D.; Ma, H.; Zhou, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, W. MicroRNA-140-5p attenuated oxidative stress in Cisplatin induced acute kidney injury by activating Nrf2/ARE pathway through a Keap1-independent mechanism. Exp. Cell. Res. 2017, 360, 292–302.

- Wang, J.; Ishfaq, M.; Xu, L.; Xia, C.; Chen, C.; Li, J. METTL3/m(6)A/miRNA-873-5p Attenuated Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Colistin-Induced Kidney Injury by Modulating Keap1/Nrf2 Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 517.

- Cheng, X.; Ku, C.H.; Siow, R.C. Regulation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway by microRNAs: New players in micromanaging redox homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 64, 4–11.

- Yin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; Min, X. Downregulation of miR-93 elevates Nrf2 expression and alleviates reactive oxygen species and cell apoptosis in diabetic retinopathy. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 12, 10235–10243.

- Zhu, J.; Wang, S.; Qi, W.; Xu, X.; Liang, Y. Overexpression of miR-153 promotes oxidative stress in MPP(+)-induced PD model by negatively regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 4179–4187.

- Yamamoto, S.; Inoue, J.; Kawano, T.; Kozaki, K.; Omura, K.; Inazawa, J. The impact of miRNA-based molecular diagnostics and treatment of NRF2-stabilized tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 58–68.

- Akdemir, B.; Nakajima, Y.; Inazawa, J.; Inoue, J. miR-432 Induces NRF2 Stabilization by Directly Targeting KEAP1. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1570–1578.

- Ishikawa, K.; Navab, M.; Lusis, A.J. Vasculitis, Atherosclerosis, and Altered HDL Composition in Heme-Oxygenase-1-Knockout Mice. Int. J. Hypertens. 2012, 2012, 948203.

- Vinchi, F.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Da Silva, M.C.; Balla, G.; Balla, J.; Jeney, V. Atherogenesis and iron: From epidemiology to cellular level. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 94.

- Gottlieb, Y.; Truman, M.; Cohen, L.A.; Leichtmann-Bardoogo, Y.; Meyron-Holtz, E.G. Endoplasmic reticulum anchored heme-oxygenase 1 faces the cytosol. Haematologica 2012, 97, 1489–1493.

- Hayashi, S.; Omata, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Higashimoto, Y.; Hara, T.; Sagara, Y.; Noguchi, M. Characterization of rat heme oxygenase-3 gene. Implication of processed pseudogenes derived from heme oxygenase-2 gene. Gene 2004, 336, 241–250.

- Ferrandiz, M.L.; Devesa, I. Inducers of heme oxygenase-1. Curr Pharm Des. 2008, 14, 473–486.

- Funes, S.C.; Rios, M.; Fernandez-Fierro, A.; Covian, C.; Bueno, S.M.; Riedel, C.A.; Mackern-Oberti, J.P.; Kalergis, A.M. Naturally Derived Heme-Oxygenase 1 Inducers and Their Therapeutic Application to Immune-Mediated Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1467.

- Ayer, A.; Zarjou, A.; Agarwal, A.; Stocker, R. Heme Oxygenases in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2016, 96, 1449–1508.

- Kishimoto, Y.; Kondo, K.; Momiyama, Y. The Protective Role of Heme Oxygenase-1 in Atherosclerotic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3628.

- Ishikawa, K.; Sugawara, D.; Wang, X.; Suzuki, K.; Itabe, H.; Maruyama, Y.; Lusis, A.J. Heme oxygenase-1 inhibits atherosclerotic lesion formation in ldl-receptor knockout mice. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 506–512.

- Orozco, L.D.; Kapturczak, M.H.; Barajas, B.; Wang, X.; Weinstein, M.M.; Wong, J.; Deshane, J.; Bolisetty, S.; Shaposhnik, Z.; Shih, D.M.; et al. Heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages plays a beneficial role in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 1703–1711.

- Yet, S.F.; Layne, M.D.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.H.; Ith, B.; Sibinga, N.E.; Perrella, M.A. Absence of heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular remodeling. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1759–1761.

- Liu, D.; He, Z.; Wu, L.; Fang, Y. Effects of Induction/Inhibition of Endogenous Heme Oxygenase-1 on Lipid Metabolism, Endothelial Function, and Atherosclerosis in Rabbits on a High Fat Diet. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 118, 14–24.

- Bao, W.; Song, F.; Li, X.; Rong, S.; Yang, W.; Zhang, M.; Yao, P.; Hao, L.; Yang, N.; Hu, F.B.; et al. Plasma heme oxygenase-1 concentration is elevated in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12371.

- Bento-Pereira, C.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Activation of transcription factor Nrf2 to counteract mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 785–802.

- Petrillo, S.; Schirinzi, T.; Di Lazzaro, G.; D’Amico, J.; Colona, V.L.; Bertini, E.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mari, L.; Mercuri, N.B.; Piemonte, F.; et al. Systemic activation of Nrf2 pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 180–184.

- Abraham, N.G.; Kappas, A. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of heme oxygenase. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008, 60, 79–127.

- Fiorelli, S.; Porro, B.; Cosentino, N.; Di Minno, A.; Manega, C.M.; Fabbiocchi, F.; Niccoli, G.; Fracassi, F.; Barbieri, S.; Marenzi, G.; et al. Activation of Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway and Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Vulnerability:an In Vitro and In Vivo Study. Cells 2019, 8, 356.

- Kishimoto, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Saita, E.; Niki, H.; Ohmori, R.; Kondo, K.; Momiyama, Y. Plasma Heme Oxygenase-1 Levels and Carotid Atherosclerosis. Stroke 2018, 49, 2230–2232.

- Cheng, C.; Noordeloos, A.M.; Jeney, V.; Soares, M.P.; Moll, F.; Pasterkamp, G.; Serruys, P.W.; Duckers, H.J. Heme oxygenase 1 determines atherosclerotic lesion progression into a vulnerable plaque. Circulation 2009, 119, 3017–3027.

- Schwertner, H.A.; Jackson, W.G.; Tolan, G. Association of low serum concentration of bilirubin with increased risk of coronary artery disease. Clin. Chem. 1994, 40, 18–23.

- Erdogan, D.; Gullu, H.; Yildirim, E.; Tok, D.; Kirbas, I.; Ciftci, O.; Baycan, S.T.; Muderrisoglu, H. Low serum bilirubin levels are independently and inversely related to impaired flow-mediated vasodilation and increased carotid intima-media thickness in both men and women. Atherosclerosis 2006, 184, 431–437.

- Novotny, L.; Vitek, L. Inverse relationship between serum bilirubin and atherosclerosis in men: A meta-analysis of published studies. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 568–571.

- Durante, W. Targeting heme oxygenase-1 in vascular disease. Curr. Drug. Targets 2010, 11, 1504–1516.

- Wang, W.W.; Smith, D.L.; Zucker, S.D. Bilirubin inhibits iNOS expression and NO production in response to endotoxin in rats. Hepatology 2004, 40, 424–433.

- Brouard, S.; Otterbein, L.E.; Anrather, J.; Tobiasch, E.; Bach, F.H.; Choi, A.M.; Soares, M.P. Carbon monoxide generated by heme oxygenase 1 suppresses endothelial cell apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1015–1026.

- Srisook, K.; Han, S.S.; Choi, H.S.; Li, M.H.; Ueda, H.; Kim, C.; Cha, Y.N. CO from enhanced HO activity or from CORM-2 inhibits both O2- and NO production and downregulates HO-1 expression in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 307–318.

- Otterbein, L.E.; Bach, F.H.; Alam, J.; Soares, M.; Tao Lu, H.; Wysk, M.; Davis, R.J.; Flavell, R.A.; Choi, A.M. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 422–428.

- Otterbein, L.E.; Foresti, R.; Motterlini, R. Heme Oxygenase-1 and Carbon Monoxide in the Heart: The Balancing Act Between Danger Signaling and Pro-Survival. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1940–1959.

- Balla, J.; Jacob, H.S.; Balla, G.; Nath, K.; Eaton, J.W.; Vercellotti, G.M. Endothelial-cell heme uptake from heme proteins: Induction of sensitization and desensitization to oxidant damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 9285–9289.

- Kumar, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 157, 175–188.

- Jeney, V.; Balla, J.; Yachie, A.; Varga, Z.; Vercellotti, G.M.; Eaton, J.W.; Balla, G. Pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of circulating heme. Blood 2002, 100, 879–887.

- Balla, J.; Vercellotti, G.M.; Jeney, V.; Yachie, A.; Varga, Z.; Jacob, H.S.; Eaton, J.W.; Balla, G. Heme, heme oxygenase, and ferritin: How the vascular endothelium survives (and dies) in an iron-rich environment. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2007, 9, 2119–2137.

- Brunet, S.; Thibault, L.; Delvin, E.; Yotov, W.; Bendayan, M.; Levy, E. Dietary iron overload and induced lipid peroxidation are associated with impaired plasma lipid transport and hepatic sterol metabolism in rats. Hepatology 1999, 29, 1809–1817.

- Rooyakkers, T.M.; Stroes, E.S.; Kooistra, M.P.; van Faassen, E.E.; Hider, R.C.; Rabelink, T.J.; Marx, J.J. Ferric saccharate induces oxygen radical stress and endothelial dysfunction in vivo. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 32 (Suppl. 1), 9–16.