Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Psychology, Clinical

Existential suffering refers to one's angst due to a perceived loss of meaning, hope, relationships, and a sense of self in thinking about death and dying. Quality palliative care not only takes care of patients’ physical and existential suffering but also fills their last days with opportunities for redemption, spiritual growth, and reconciliation. We propose a holistic approach as illustrated by the healing wheel, involving health care providers, the community, patients, and a Higher Power.

- palliative care

- meaning therapy

- CALM therapy

- COVID-19

- existential positive psychology

- good death

- wellbeing

- mature happiness

- flourishing

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the inadequacies of palliative care services with over 4 million deaths and 100 million confirmed cases. All healthcare workers, including palliative care workers, have faced severe challenges such as shortage of beds and staff, long working hours, and a lack of personal protective equipment [1][2][3]. The Toronto palliative care situation illustrates the need to integrate palliative care into COVID-19 management, and to optimize it for the pandemic [4].

Demographic trends also demand strategic thinking and planning in order to meet the challenge of increased demands for palliative care because of increased longevity accompanied by an increase in psychological needs, such as meaning for living, will to live, and death acceptance [5][6][7]. The existential crisis is especially severe for those who are approaching the end of life with cumulative losses in all areas of life.

For end-of-life care, the best medicine is compassion: “The word compassion means ‘to suffer with.’ Compassionate care calls physicians to walk with people in the midst of their pain, to be partners with patients rather than experts dictating information to them.” [8]. “We are at our best, when we serve each other”, wrote Byock [9], one of the foremost palliative care physicians in the US. He argued that the healthcare system should not be dominated by high-tech procedures and a philosophy to “fight disease and illness at all costs.” To ensure the best possible elder care, we must not only remake our healthcare system, but also move beyond our cultural aversion to thinking about death.

2. Recent Research on Existential Anxieties and Wellbeing in Palliative Patients

2.1. Meaning-Centered Approach to End-of-Life Care

Given the prevalent loss of meaning and dignity in palliative patients, meaning-centered therapies demonstrated efficacy in improving spiritual wellbeing, sense of dignity, and meaning, and decreasing depression, anxiety, and desire for [10][11][12]. A sense of dignity, defined as “quality or state of being worthy, honored, or esteemed” [13], is importantly related to personal meaning. Dignity Therapy [14] is primarily concerned with what has been meaningful in the life of the patients and the legacy patients wants to pass on to family and loved ones.

Another scientifically validated meaning-centered therapy for advanced cancer is Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy [15]. Its aim is to sustain and enhance a sense of meaning in the face of existential crisis. Based on Frankl’s logotherapy, the protocol of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy [16] is composed of 7–8 sessions in which patients reflect on the concept of meaning and the impact that cancer has produced on their life and identity.

Breitbart’s meaning-centered group therapy for cancer patients [17] aims to help expand possible sources of meaning by teaching the philosophy of meaning, providing group exercises and homework for each individual participant, and by open-ended discussion. The eight group sessions are categorized under the following specific themes of meaning relevant to cancer patients:

-

Session 1—Concepts of meaning and sources of meaning

-

Session 2—Cancer and meaning

-

Sessions 3 and 4—Meaning derived from the historical context of life

-

Session 5—Meaning derived from attitudinal values

-

Session 6—Meaning derived from creative values and responsibility

-

Session 7—Meaning derived through experiential values

-

Session 8—Termination and feedback.

2.2. Wong’s Pioneering Work on Death Acceptance

Wong’s integrative meaning therapy is based on his pioneer work on death acceptance.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross [18] stage-model of coping with death (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance) was a milestone in death studies. Approximately 30 years later, Wong and his associates undertook a comprehensive study on death acceptance, which led to the development of the Death Attitudes Profile (DAP) [19] and the Death Attitudes Profile Revised (DAP-R) [20]. Both scales have been widely used worldwide.

In addition to death fear and death avoidance, Wong and associates identified three distinct types of death acceptance: (1) neutral death acceptance—accepting death rationally as part of life; (2) approach acceptance—accepting death as a gateway to a better afterlife; and (3) escape acceptance—choosing death as a better alternative to a painful existence.

Approach acceptance is rooted in religious/spiritual beliefs in a desirable afterlife. To those who embrace such beliefs, the afterlife is more than symbolic immortality, thus offering hope and comfort to the dying as well as the bereaved. Escape acceptance is primarily based on the perception that death offers a welcome relief from the unbearable pain and meaninglessness of staying alive. The construct of neutral acceptance means to accept the reality of death in a rational manner and make best use of one’s limited time on earth.

Approach acceptance may also incorporate neutral acceptance with regard to making the best use of our finite life on earth, but it has the advantage that belief in an afterlife can be a source of comfort and hope in the face of death. Maybe that is why most people believe in heaven or an afterlife [21].

Consistent with Wong’s dual-system model, death anxiety and death acceptance can co-exist. Some form of death anxiety is always present over a wide range of factors, such as ultimate loss, fear of the pain and loneliness of dying, fear of failing to complete one’s life work, the uncertainty of what follows death, annihilation anxiety or fear of non-existence, and worrying about the survivors after one’s death. Even with the constant presence of some level of death anxiety, one can achieve death acceptance through three stages: (1) avoiding death, (2) confronting or facing death, and (3) accepting or embracing death.

2.3. Meaning Management and Death Acceptance

Meaning plays an important role in death acceptance because once one has found something worth dying for, one is no longer afraid of death. Meaning-making can help us rise above fear of death and motivate us to strive towards something that is bigger and longer lasting than ourselves. Personally, I (the first author) have gone through the same existential struggles of finding meaning when coping with cancer [22] and loneliness during hospitalization [23].

Wong has described the meaning management theory (MMT) as a conceptual framework to understand and facilitate death acceptance [24]. MMT is based on the existential positive psychology and dual-system model described earlier. According to MMT, it is more productive and fulfilling to confront our death anxiety courageously and honestly and at the same time passionately pursue a meaningful goal [25][26].

MMT is more than cognitive reframing or rationalization. It actually requires a fundamental shift to from pleasure-seeking to the meaning mindset [27], and from self-centeredness to self-transcendence [28]. Meaning therapy [29][30] equips people to squeeze out meaning and hope even from the darkest moments of life.

2.4. Some Key Concepts of IMT in Palliative Care

In addition to helping palliative care patients work through their suffering and come to the point of death acceptance through meaning seeking, we want to briefly explain (1) the concept of meaning, (2) the importance of faith, hope, and love, (3) the importance of courage, acceptance, and transformation, and (4) provide a few practical tips for palliative care workers (for details regarding IMT, please read [31]):

-

Wong’s Definition of Meaning. Meaning has been defined by different researchers differently. Wong [29] proposes that a comprehensive way to clarify the concept of meaning is PURE (purpose, understanding, responsibility, and enjoyment):

- (a)

-

A meaningful life is purposeful. We all have the desire to be significant, we all want our lives to matter. The intrinsic motivation of striving to improve ourselves to achieve a worth goal is a source of meaning (as in the movie Ikiru). That is why purpose is the cornerstone of a meaningful life. Even if you want to live an ordinary life, you can still do your best to improve yourself as a good parent, spouse, neighbor, or a decent human being.

- (b)

-

A meaningful life is understandable or coherent. We need to know who we are, the reasons for our existence, or the reason or objective of our actions [32]. Having a cognitive understanding or a sense of coherence is equally important for meaning.

- (c)

-

A meaningful life is a responsible one. We must assume full responsibility for our life or for choosing our life goal. Self-determination is based on the responsible use of our freedom. This involves the volition aspect of personality. That is why for both Frankl [33] and Peterson [34] have noted that responsibility equals meaning.

- (d)

-

A meaningful life is enjoyable and fulfilling. It is the deep life satisfaction that comes from having lived a good life and made some difference in the world. This is a natural by-product of self-evaluation that “my life matters”.

Together, these four criteria constitute the PURE definition of meaning in life. Most meaning researchers support a tripartite definition of meaning in life: comprehension, purpose, and mattering [35][36]. However, these elements are predicated on the assumption that individuals assume the responsibility to choose the narrow path of meaning rather than the broad way of hedonic happiness.

In the existential literature, freedom and responsibility are essential values for an authentic and meaningful life (Frankl, Rollo May, Irvin D. Yalom, Emmy van Deuzen, etc.). For instance, my (the first author) life is meaningful because I chose the life goal of reducing suffering, as well as bringing meaning and hope to suffering people. This was not an easy choice, but it was the only choice if I wanted to be true to my nature and my calling.

- 2.

-

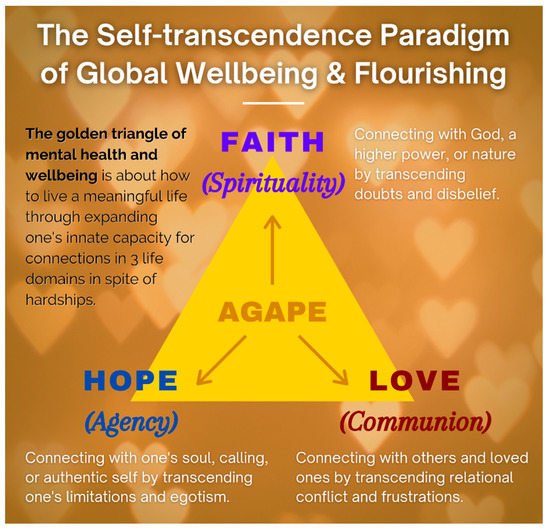

The Golden Triangle of Faith, Hope, and Love: We have a serious mental health crisis because we are like fish out of water, living in a materialistic consumer society and a digital world without paying much attention to our spiritual needs. Technological progress contributes to our physical wellbeing, but it also destroys the soul if we do not make an intentional effort to care for our soul. IMT aims to help people get back into the water—to meet people’s basic psychological needs for loving relationships, a meaningful life, and faith in God and some transcendental values, as shown in the symbol of the Golden Triangle (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Golden Triangle.

Figure 1. The Golden Triangle.

Briefly, faith in God or a higher power represent our spiritual core value:

- (a)

-

The power of IMT is derived from faith—faith in a better future, in the self, in others, in God, and in a happy afterlife. It does not matter whether you have faith in Jesus, Buddha, or in your medical doctors. If you have faith in someone or something greater than yourself, you will have a better chance of overcoming seemingly insurmountable problems. Faith, nothing but faith, can counteract the horrors of life and death. For Frankl, faith is the key to healing:“The prisoner who had lost faith in the future—his future—was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and become subject to mental and physical decay.”([33], p. 95)

- (b)

-

Hope represents one’s role as an agent to discover one’s true calling and work towards a better future. Even palliative care patients can work towards a better tomorrow. The saddest thing my (the first author) father said to me during my last visit to Hong Kong was “I have no hope. I’m going to die soon, and none of my children are interested in taking over my business”. This was because he had no hope beyond his own personal interest. Tragic optimism [37][38] enables one to transcend such hopelessness.

- (c)

-

Love for others and developing connections indicate that we are always part of a larger whole, and relationships are a major source of meaning of life [39]. By withholding love, people perish due to loneliness and meaninglessness. Do we realize that love is the most powerful force on earth? Do we know that love can give us the strength to endure anything, the courage to face any danger, and the joy to make sacrifices for others?

Faith, hope, and love are as essential to our mental health as air, food, and water are essential to our physical health. This positive triad, as depicted by the golden triangle, has enabled humanity to survive since the beginning of time; it is still essential in overcoming depression, addiction, and suffering, and creating a better future. Wellbeing even in palliative care patients, can be conceptualized in terms of the golden triangle.

- 3.

-

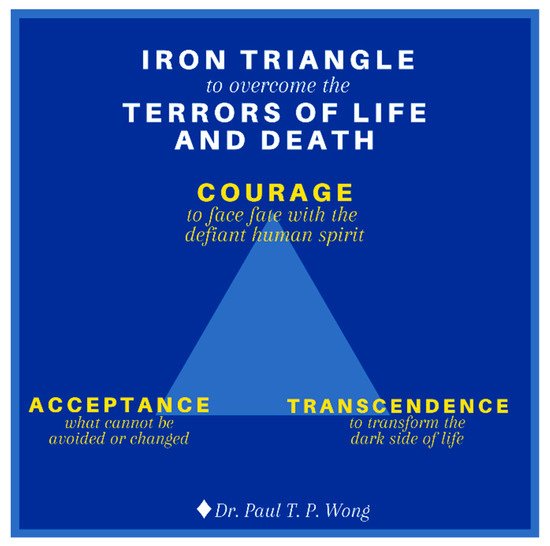

The Iron Triangle of Courage, Acceptance, and Transformation. Life is tough, especially during old age with all the inevitable losses. During the end-of-life stage, one needs a lot of courage to face all the challenges associated with death and dying [40]. One needs courage to cope with the distress of sickness and dying, to accept all the losses, and for the final exit. One also needs courage to connect with their own inner resources, family, and community in order to enhance their dignity and well-being. The main thrust of my (the first author) recent book [41] is that we are wired in such a way that our genes and brain have the necessary capacities to survive and thrive in any adverse situations, provided that we are awakened to our spiritual nature and cultivate our psychological resources. In addition to the golden triangle, our other resources come from the iron triangle of courage, acceptance, and transcendence as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The Iron Triangle.

Figure 2. The Iron Triangle.

- (a)

-

Existential courage is the courage “necessary to make being and becoming possible” ([42], p. 4). As discussed earlier, existential courage is needed in all stages of human development: The courage to embrace the dark side of human existence makes it possible for us make positive changes, to face what cannot be changed or is beyond our control, and to transform all the setbacks and obstacles. The most comprehensive treatment of courage can be found in Yang et al. [43]. They treat courage as a spiritual concept “similar to the existential thoughts of the will to power.” (p. 13). In their words, “To Adler, the will to power is a process of creative energy or psychological force desiring to exert one’s will in overcoming life problems.” (p. 12). Courage is also similar to Frankl’s [33] defiant power of the human spirit.

Courage unleashes the hidden strength and optimism in us to forge ahead in spite of the dangers, obstacles, and sufferings; courage is an attitude of affirmation, of saying “Yes” no matter what, an attitude that has been steeled by prior experience of overcoming adversities and hardships [44].

Existential courage consists of the courage to be true to oneself (authenticity), the courage to belong to a group or serve others (horizontal self-transcendence), and the courage to believe and trust in God or a higher power (vertical self-transcendence). Such existential courage encompasses the three vital connections covered by the golden triangle. In sum, courage is a matter of the heart and the will. It is an attitude of affirmation and optimism that enables one to have the true grit to face whatever life throws at them.

- (b)

-

Death acceptance is the other side of life acceptance. David Kuhl [45] writes:

“Do I embrace life, or do I prepare to die? And for all of us, the answers are ultimately similar. Living fully and dying well involve enhancing one’s sense of self, one’s relationships with others, and one’s understanding of the transcendent, the spiritual, and the supernatural. And only in confronting the inevitability of death does one truly embrace life.”

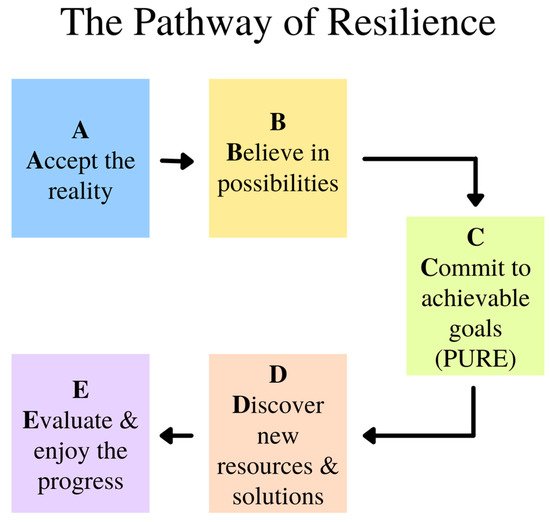

The pathway towards resilience is shown in Figure 3 and explained in Wong [46]. Acceptance is also the first step in facing death anxiety. We are more likely to embrace life when we recognize the spiritual values in the life–death cycle, celebrate the completion of our life’s mission, and live life to the fullest right up to the final moment. There are different levels of acceptance: cognitive, emotional, realistic, existential, and transformative. Death acceptance can transform our life only if we accept it at the deepest existential level.

Figure 3. The Pathway of Resilience.

- (c)

-

There are different pathways in transforming negative events and emotions into wellbeing [47][48]. Transformative coping takes on different forms, such as reframing, re-authoring, or recounting one’s life event in terms of a larger narrative or meta-story. For palliative care patients, life review or reminiscence [49] and small self-transcendental acts, as shown in Ikiru, seems most helpful. In life review, we ask patients to reflect on the following questions: What are your happiest moments (with someone special in your life)? What is your best early memory? What are your proudest moments (for your achievement and contribution)? What are your most meaningful moments?

- 4.

-

Some Practical Tips in Palliative Counselling. Here are some practical tips to help transform a victim’s journey into a hero’s adventure and discover meaning and hope in boundary situations. IMT seeks to awaken the client’s sense of responsibility and meaning, and guide them to (a) achieve a deeper understanding of the problems from a larger perspective and (b) discover their true identity and place in the world.

The transformative approach to spiritual care is based on what you say and do with patients rather than what you do to the patients. “Serving patients may involve spending time with them, holding their hands, and talking about what is important to them.” [8]. It often includes the following elements in a healing relationship:

-

The healing silence—listening to the inner voice.

-

The healing touch—touching the heart and soul.

-

The healing connection—establishing an I–You relationship.

-

The healing presence—providing a caring, compassionate presence.

-

The healing process—nurturing spiritual growth.

Self-transcendence is a natural way to prepare us for finally transcending our physical self and the material world. Lucas [50] is correct that self-transcendence is “the best possible help” for palliative care patients because it broadens their values, opens the door for them to discover something worthy of self-transcendence, and it enables them to find meaning and happiness.

Here are a few methods of engaging in meaningful or self-transcendental activities:

- (1)

-

Do some random acts of kindness to others.

- (2)

-

Engage in creative or worthwhile work as a gift to the community or family.

- (3)

-

Reach out to get reconciled with estranged loved ones.

- (4)

-

Make a useful contribution to society.

- (5)

-

Be true to oneself and do something one has always wanted to do.

- (6)

-

Construct a coherent life story with photos as a legacy to one’s family.

Encourage them to reflect on the following self-affirmations:

-

I believe that life has meaning until my last breath.

-

I am grateful that the reality of suffering and death has showed me what I was meant to be.

-

I can live a happy and meaningful life until my last breath.

-

Life has been very tough but I am grateful that I have overcome its obstacles.

-

I have my regrets but I have found forgiveness.

Practical tips in spiritual care:

-

Show compassion through gentle touch (e.g., holding hand) and smile.

-

Ask them if there is anything you can do for them.

-

Ask them about any concerns (e.g., someone they want to see).

-

Help them see that they have lived a life of meaning and purpose.

-

Assure them their life stories are worth telling and remembering.

-

Assure them they have made a difference in the lives of others.

-

Assure them they can still have hope beyond death through faith.

-

Assure them that they can accept death with inner peace.

-

Offer a prayer if it seems appropriate.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/medicina57090924

References

- Hannon, B.; Mak, E.; Al Awamer, A.; Banerjee, S.; Blake, C.; Kaya, E.; Lau, J.; Lewin, W.; O’Connor, B.; Saltman, A.; et al. Palliative care provision at a tertiary cancer center during a global pandemic. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2501–2507.

- Oluyase, A.O.; Hocaoglu, M.; Cripps, R.L.; Maddocks, M.; Walshe, C.; Fraser, L.K.; Preston, N.; Dunleavy, L.; Bradshaw, A.; Murtagh, F.E.; et al. The Challenges of Caring for People Dying from COVID-19: A Multinational, Observational Study (CovPall). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 460–470.

- Pastrana, T.; De Lima, L.; Pettus, K.; Ramsey, A.; Napier, G.; Wenk, R.; Radbruch, L. The impact of COVID-19 on palliative care workers across the world: A qualitative analysis of responses to open-ended questions. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 19, 187–192.

- Wentlandt, K.; Cook, R.; Morgan, M.; Nowell, A.; Kaya, E.; Zimmermann, C. Palliative Care in Toronto During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, 615–618.

- Araújo, L.; Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Paúl, M.C. Successful aging at 100 years: The relevance of subjectivity and psychological resources. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2016, 28, 179–188.

- Wong, P.T. Personal meaning and successful aging. Can. Psychol. Can. 1989, 30, 516–525.

- Wong, W.-C.P.; Lau, H.-P.B.; Kwok, C.-F.N.; Leung, Y.-M.A.; Chan, M.-Y.G.; Chan, W.-M.; Cheung, S.-L.K. The well-being of community-dwelling near-centenarians and centenarians in Hong Kong a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2014, 14, 63.

- Puchalski, C.M. The Role of Spirituality in Health Care. Bayl. Univ. Med. Cent. Proc. 2001, 14, 352–357.

- Byock, I. The Best Care Possible: A Physician’s Quest to Transform Care through the End of Life; Avery: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Breitbart, W.; Poppito, S.; Rosenfeld, B.; Vickers, A.; Li, Y.; Abbey, J.; Olden, M.; Pessin, H.; Lichtenthal, W.; Sjoberg, D.; et al. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1304–1309.

- Breitbart, W.; Rosenfeld, B.; Gibson, C.; Pessin, H.; Poppito, S.; Nelson, C.; Tomarken, A.; Timm, A.K.; Berg, A.; Jacobson, C.; et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology 2009, 19, 21–28.

- Chochinov, H.M.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Breitbart, W.; McClement, S.; Hack, T.; Hassard, T.; Harlos, M. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally ill patients: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 753–762.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Arslan, G.; Bowers, V.L.; Peacock, E.J.; Kjell, O.N.E.; Ivtzan, I.; Lomas, T. Self-transcendence as a buffer against COVID-19 suffering: The development and validation of the self-transcendence measure-B. Frontiers 2021, in press.

- Hack, T.F.; McClement, S.; Chochinov, H.M.; Cann, B.J.; Hassard, T.H.; Kristjanson, L.J.; Harlos, M. Learning from dying patients during their final days: Life reflections gleaned from dignity therapy. Palliat. Med. 2010, 24, 715–723.

- Breitbart, W.; Applebaum, A. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy. In Handbook of Psychotherapy in Cancer Care; Watson, M., Kissane, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 137–148.

- Breitbart, W.; Poppito, S. Individual Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Treatment Manual; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014.

- Breitbart, W.; Gibson, C.; Poppito, S.R.; Berg, A. Psychotherapeutic Interventions at the End of Life: A Focus on Meaning and Spirituality. Can. J. Psychiatry 2004, 49, 366–372.

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying; Scribner: New York, NY, USA, 1997.

- Gesser, G.; Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T. Death Attitudes across the Life-Span: The Development and Validation of the Death Attitude Profile (DAP). Omega J. Death Dying 1988, 18, 113–128.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Reker, G.T.; Gesser, G. Death Attitude Profile–Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. In Death Anxiety Handbook: Research Instrumentation and Application; Neimeyer, R.A., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 121–148.

- Bethune, B. Why So Many People—Including Scientists—Suddenly Believe in an Afterlife: Heaven is Hot Again, and Hell is Colder Than Ever. Maclean’s. Available online: http://www.macleans.ca/society/life/the-heaven-boom/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Wong, P.T.P. Living with Cancer, Suffering, and Death: A Case for PP 2.0. (Autobiography, Ch. 27). DrPaulWong.com. Available online: http://www.drpaulwong.com/living-with-cancer-suffering-and-death-a-case-for-pp-2-0-autobiography-ch-27/ (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Wong, P.T.P. A meaning-centered approach to overcoming loneliness during hospitalization, old age, and dying. In Addressing Loneliness: Coping, Prevention and Clinical Interventions; Sha’ked, A., Rokach, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 171–181.

- Wong, P.T.P. Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes; Tomer, A., Eliason, G.T., Wong, P.T.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 65–87.

- Tomer, A.; Eliason, G.T.; Wong, P.T.P. (Eds.) Existential and Spiritual Issues in Death Attitudes; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2008.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Tomer, A. Beyond Terror and Denial: The Positive Psychology of Death Acceptance. Death Stud. 2011, 35, 99–106.

- Wong, P.T.P. What is the meaning mindset? Int. J. Existent. Psychol. Psychother. 2012, 4, 1–3.

- Wong, P.T.P. Self-Transcendence: A Paradoxical Way to Become Your Best. Int. J. Existent. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 6, 9. Available online: http://journal.existentialpsychology.org/index.php/ExPsy/article/view/178 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Wong, P.T.P.; Gingras, D. Finding Meaning and Happiness While Dying of Cancer: Lessons on Existential Positive Psychology. PsycCritiques 2010, 55.

- Wong, P.T.P. (Ed.) The Human Quest for Meaning: Theories, Research, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Wong, P.T.P. Existential positive psychology and integrative meaning therapy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 565–578.

- Antonovsky, A. The Jossey-Bass Social and Behavioral Science Series and the Jossey-Bass Health Series. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987.

- Frankl, V.E. Man’s Search for Meaning; Washington Square Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985.

- Peterson, J.B. 12 Rules for Life: An Antidote to Chaos; Random House Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018; ISBN 978-0-345-81602-3.

- George, L.S.; Park, C.L. Meaning in Life as Comprehension, Purpose, and Mattering: Toward Integration and New Research Questions. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2016, 20, 205–220.

- Martela, F.; Steger, M.F. The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 531–545.

- Leung, M.M.; Arslan, G.; Wong, P.T.P. Tragic Optimism as a Buffer against COVID-19 Suffering and the Psychometric Properties of a Brief Version of the Life Attitudes Scale (LAS-B). Frontiers 2021, 12, 2800.

- Wong, P.T.P. Compassion: The hospice movement. In The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization; Kurian, G., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009.

- Wong, P.T.P. Implicit theories of meaningful life and the development of the Personal Meaning Profile. In The Human Quest for Meaning: A Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications; Wong, P.T.P., Fry, P., Eds.; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 111–140.

- Wong, P.T.P. Meaning Therapy: An Integrative and Positive Existential Psychotherapy. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2009, 40, 85–93.

- Wong, P.T.P. Made for Resilience and Happiness: Effective Coping with COVID-19; INPM Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020.

- May, R. The Courage to Create; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1975.

- Yang, J.; Milliren, A.; Blagen, M. The Psychology of Courage: An Adlerian Manual of Healthy Social Living; Routledge: London, UK, 2010.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Worth, P. The deep-and-wide hypothesis in giftedness and creativity. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 54, 11–23.

- Kuhl, D. What Dying People Want: Practical Wisdom for the End of Life; Anchor Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003.

- Wong, P.T.P. Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy; Russo-Netzer, P., Schulenberg, S.E., Batthyány, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 323–342.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Wenzel, A. Coping and Stress. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology; Wenzel, A., Ed.; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 886–890.

- Wong, P.T.P.; Wong, L.C.J.; Scott, C. Beyond stress and coping: The positive psychology of transformation. In Handbook of Multicultural Perspectives on Stress and Coping; Wong, P.T.P., Wong, L.C.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–26.

- Wong, P.T.; Watt, L.M. What types of reminiscence are associated with successful aging? Psychol. Aging 1991, 6, 272–279.

- Lucas, A.M. Introduction to The Disciplinefor Pastoral Care Giving. J. Health Care Chaplain. 2000, 10, 1–33.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!