Abstract

Dentin–pulp complex is a term which refers to the dental pulp (DP) surrounded by dentin along its peripheries. Dentin and dental pulp are highly specialized tissues, which can be affected by various insults, primarily by dental caries. Regeneration of the dentin–pulp complex is of paramount importance to regain tooth vitality. The regenerative endodontic procedure (REP) is a relatively current approach, which aims to regenerate the dentin–pulp complex through stimulating the differentiation of resident or transplanted stem/progenitor cells. Hydrogel-based scaffolds are a unique category of three dimensional polymeric networks with high water content. They are hydrophilic, biocompatible, with tunable degradation patterns and mechanical properties, in addition to the ability to be loaded with various bioactive molecules. Furthermore, hydrogels have a considerable degree of flexibility and elasticity, mimicking the cell extracellular matrix (ECM), particularly that of the DP. The current review presents how for dentin–pulp complex regeneration, the application of injectable hydrogels combined with stem/progenitor cells could represent a promising approach. According to the source of the polymeric chain forming the hydrogel, they can be classified into natural, synthetic or hybrid hydrogels, combining natural and synthetic ones. Natural polymers are bioactive, highly biocompatible, and biodegradable by naturally occurring enzymes or via hydrolysis. On the other hand, synthetic polymers offer tunable mechanical properties, thermostability and durability as compared to natural hydrogels. Hybrid hydrogels combine the benefits of synthetic and natural polymers. Hydrogels can be biofunctionalized with cell-binding sequences as arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD), can be used for local delivery of bioactive molecules and cellularized with stem cells for dentin–pulp regeneration. Formulating a hydrogel scaffold material fulfilling the required criteria in regenerative endodontics is still an area of active research, which shows promising potential for replacing conventional endodontic treatments in the near future.

- Hydrogels

- Ploymers

- Stem Cells

- Tissue engineering

- Dentin-pulp Complex

- Regeneration

1. Introduction

Dentin–pulp complex is a term referring to the dental pulp surrounded by dentin along its peripheries. It reflects the close anatomical and functional relationship that exists between the dentin and dental pulp [3]. Dentin and dental pulp are highly specialized tissues, where the dental pulp is a vascular connective tissue responsible for the maintenance of tooth vitality, while dentin is the protective tissue for this vital pulp [4,5,6]. Maintaining dentin/pulp integrity and vitality are of importance for all dental practitioners and researchers [7]. Dental caries, among other insults to the tooth structure, can result in irreversible pulpal damage with devastating effects. Regeneration of the dentin–pulp complex to regain tooth vitality remains to be of paramount importance.

For damaged pulp tissue, direct and indirect pulp capping are considered to be the first line of treatment to maintain the pulpal tissue vitality, while the endodontic treatment, relying on three-dimensional shaping, cleaning and filling of the pulpal soft tissue space within the tooth via a biocompatible inert material, leads to loss of pulp vitality with its consequences on the integrity of the tooth structure. On the other hand, dentin–pulp complex regeneration through regenerative endodontic procedure (REP) [15,16] or revascularization relies on stimulating the differentiation of resident stem/progenitor cells [17]. REP involves the induction of intracanal bleeding and the formation of a blood clot, which act as a scaffold for stem/progenitor cells from the apical dental papilla (SCAP) migration and differentiation for regeneration [18].

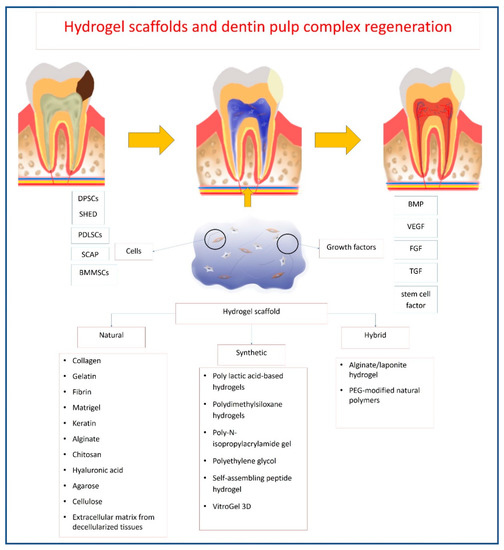

Dentin–pulp complex regeneration could also include approaches for replacing/repairing the damaged pulp tissues through tissue engineering approaches. Different tissue engineering approaches depend basically on the combination of three components: cells, bioactive molecules and scaffolds. Stem/progenitor cells investigated in the field of dentin–pulp complex regeneration include stem/progenitor cells of exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED), periodontal ligament stem/progenitor cells (PDLSCs), DPSCs, SCAP, and dental follicle stem/progenitor cells [23]. BMP, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), FGF-2 and TGF are the principal morphogens used frequently in conjunction with dental stem/progenitor cells to induce a variety of cellular activities and induce various tissue structures, even when used at very low concentrations [1].

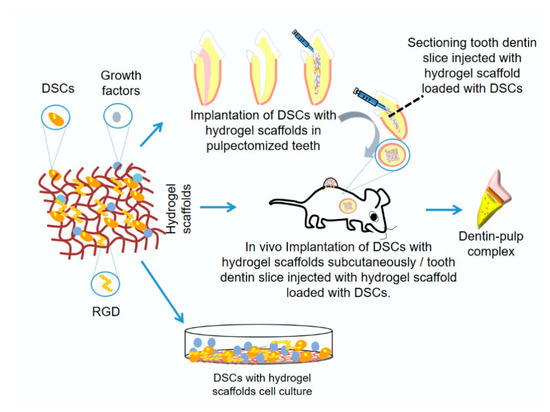

Recently, hydrogel-based scaffolds were introduced in the field of tissue engineering. They are a unique category of three-dimensional (3D) polymeric networks with water as the liquid component. Their hydrophilic nature renders them able to retain high water content and biological fluids, as well as diffusion of nutrients through their structure. In addition to their biocompatibility, their expected degradation pattern and their adjustable mechanical properties, they can maintain their network integrity and thus do not dissolve in high water concentrations due to their crosslinking structure. Furthermore, hydrogels have a considerable degree of flexibility and elasticity similar to a natural ECM, providing the essential cell support needed during tissue regeneration. Thus, they are considered an optimal choice for many tissue engineering applications due to such unique characteristics, in addition to their gelatinous structure and their ability to be loaded with different drugs, making them successful drug delivery system [7,27,28,29] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing hydrogel scaffold for dentin/pulp regeneration research methods.

2. Requirements of Ideal Hydrogel Scaffold for Dentin–Pulp Complex Regeneration

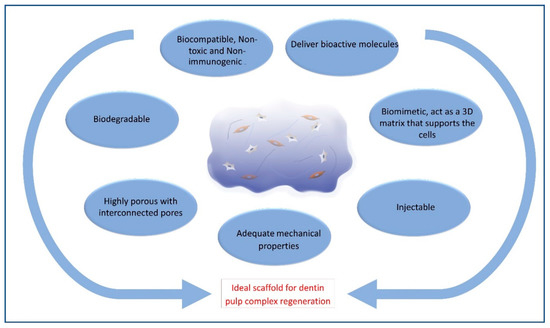

The ideal materials used for dentin–pulp complex regeneration (Figure 2) should be biocompatible and clinically applicable. They should be sterilizable, easy to use and apply, have the ability to be stored at clinical settings, with a reasonable shelf-life, injectable to adapt to canal morphology, have short setting times and be without any discomfort to the patient[1][2]. Scaffolds should also be cost-effective to allow mass production for clinical translation[3].

Figure 2. Schematic diagram showing criteria of ideal hydrogel scaffold.

3. Mechanism of Action of Hydrogels in Dentin–Pulp Regeneration

The hydrogels’ mechanisms of action in vivo include their role as a space filling material, in addition to their roles as carriers for cells and bioactive molecules[4]. Hydrogels should maintain the desired volume and structural integrity for the required time to perform this function[4]. For dentin–pulp complex regeneration, hydrogels act as carriers of stem/progenitor cells with odontogenic potential, such as DPSCs[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12], odontoblasts-like cells [13][14][15], HUVECs[9][16], SCAP[17][18], SHED[11][19][20][21], BMMSCs[11][22][23][24][25], PDLSCs[11], endothelial cells[23] and primary dental pulp cells[26]. They can also act as carriers for the local delivery of antibiotics, such as clindamycin[27] and bioactive molecules, aiming to promote tissue regeneration, such as VEGF[6][28], FGF [28][29][30], BMP[10], TGF-β1[31], stem cell factor[32], dentonin sequence[33] and RGD cell-binding motifs[33]. Once implanted in site, being biodegradable, hydrogels allow the release of bioactive molecules that influence the surrounding environment (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic diagram showing mechanism of hydrogel action for dentin–pulp complex regeneration.

4. Hydrogels Used in Dentin–Pulp Complex Regeneration

Table 1. Natural hydrogels.

| Natural Hydrogels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Hydrogel Used | Type of Study | Hydrogel Modification | Hydrogel Properties | Cells Used | Upregulated Biological Molecules | Outcomes |

| Collagen Hydrogel | |||||||

| Souron et al., 2014 | Collagen | In vivo | 3D collagen matrices, mimic in vivo cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions, and regulate cell growth | Rat pulp cells labeled with indium-111-oxine | 1 month following implantation, active fibroblasts, new blood vessels and nervous fibers were present in the cellularized 3D collagen hydrogel. | ||

| Kwon et al., 2017 | Collagen | In vitro | Crosslinked with cinnamaldehyde (CA). | Crosslinked collagen with shorter gelation time enhances cellular adhesion. Higher stiffness enhances odontogenic differentiation. | Human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) | Dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), Dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP-1), Matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE), Osteonectin (ON) |

CA shortened the setting time, increased compressive strength and surface roughness of collagen hydrogels. CA-crosslinked hydrogels promoted the proliferation and odontogenic differentiation of human DPSCs |

| Pankajakshan et al., 2020 | Collagen | In vitro | Varying hydrogel stiffnesses through varying oligomer concentrations. Incorporation of Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) into 235 Pa collagen or Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) into the 800 Pa ones. |

Stiffness affect cytoskeletal organization and cell shape and specify stem cell lineage. | DPSCs | von Willebrand Factor (vWF), platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1), vascular endothelial-cadherin |

Collagen hydrogels with tunable stiffness supported cell survival, and favored differentiation of cells to a specific lineage. DPSCs cultured in 235 Pa matrices showed an increased expression of endothelial markers, cells cultured in 800 Pa showed increased alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and Alizarin S staining. |

| Gelatin Hydrogel | |||||||

| Kikuchi et al., 2007 | Gelatin hydrogel | In vivo | Crosslinked gelatin hydrogel microspheres were impregnated with fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2) and mixed with collagen sponge pieces. | Gelatin hydrogel microspheres (the water content is 95 vol%; diameters ranged from 5–15 µm; the average of diameter was 10 µm) |

DSPP | Controlled release of FGF2 from gelatin hydrogels induced the formation of dentin-like particles with dentin defects above exposed pulp. | |

| Ishimatsu et al., 2009 | Gelatin hydrogel | In vivo | Gelatin hydrogel microspheres incorporating FGF-2. | Gelatin hydrogel microspheres (the water content is 95 vol%, the average diameter was 10 µm) |

DMP-1 | Dentin regeneration on amputated pulp can be regulated by adjusting the dosage of FGF-2 incorporated in biodegradable gelatin hydrogels. | |

| Nageh et al., 2013 | Gelatin hydrogel | Clinical trial | FGF incorporated in gelatin hydrogel. | Acidic gelatin hydrogel microspheres with a mean diameter of 59 µm and 95.2% water content. | Follow-up X-ray revealed an increase in root length and width with a reduction in apical diameter confirming the root’s development. | ||

| Bhatnagar et al., 2015 | Gelatin hydrogel | In vitro | enzymatically crosslinked with microbial transglutaminase (mTG). | Hard and soft gelatin–mTG gels consist of 1.125 mL and 1.488 mL of a 10% gelatin solution with 0.375 mL (3:1 (v/v) gelatin: mTG), and 0.012 mL (125:1 (v/v) gelatin: mTG) of mTG respectively |

DPSCs | Osteocalcin (OCN), ALP, DSPP |

Enzymatically crosslinked gelatin hydrogels are a potential effective scaffold for dentin regeneration regardless of matrix stiffness or chemical stimulation using dexamethasone. |

| Miyazawa et al., 2015 | Gelatin hydrogel | In vitro In vivo |

Simvastatin-lactic acid grafted gelatin micelles, mixed with gelatin, followed by chemical crosslinking to form gelatin hydrogels. | Carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) value of micelles was 79 μg/mL. Water solubilization of Simvastatin 43 wt.%. Simvastatin in the gelatin 3.23 wt.%. The sizes of granules 500 μm with rough surfaces and uniformly sized pores | DPSCs | ALP, Dentin sialoprotein (DSP), BMP-2 |

It is possible to achieve odontoblastic differentiation of DPSCs through the controlled release of Simvastatin from gelatin hydrogel. |

| Gelatin Methacrylate Hydrogel | |||||||

| Athirasala et al., 2017 | Gelatin Methacrylate hydrogel (GelMA) | In vitro | Gelatin with methacrylic anhydride. | GelMA hydrogels of 5, 10 and 15% (w/v) concentrations showed a honeycomb-like structure. Both 10% and 15% hydrogel groups appeared to have smaller pore sizes than 5% GelMA. | Odontoblasts like cells (OD21) and endothelial colony- forming cells | Pre-vascularized hydrogel scaffolds with microchannels fabricated using GelMA is a simple and effective strategy for dentin–pulp complex regeneration. | |

| Khayat et al., 2017 | GelMA | In vivo | Gelatin with methacrylic anhydride. | DPSCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | GelMA hydrogel combined with human DPSC/human umbilical vein endothelial cells as promising pulpal revascularization treatment to regenerate human dental pulp tissues. | ||

| Ha et al., 2020 | GelMA | In vitro | Gelatin with methacrylic anhydride hydrogels of increasing concentrations. | Increasing polymer concentrations from 5% to 10% and 15% (w/v), resulting in increasing extents of crosslinking. The elastic moduli of hydrogels, increased with increase in polymer concentration from 1.7 kPa for 5% GelMA to 7 kPa and 16.4 kPa for 10% and 15% GelMA hydrogels, respectively. |

stem cells of the apical papilla (SCAP) | Substrate mechanics and geometry have a statistically significant influence on SCAP response. | |

| Park et al., 2020 | GelMA | In vitro | GelMA conjugated with synthetic BMP-2 mimetic peptide prepared into bioink. | GelMA exhibited a ~2 kPa storage modulus (G’) before crosslinking and ~4 kPa after crosslinking. | DPSCs | DSPP, OCN | BMP peptide-tethering bioink could accelerate the differentiation of human DPSCs in 3D bioprinted dental constructs. |

| Jang et al., 2020 | GelMA | In vitro In vivo |

Thrombin solution added to GelMA hydrogel. | DPSCs | Gelatin hemostatic hydrogels may serve as a viable regenerative scaffold for pulp regeneration. | ||

| Fibrin Hydrogel | |||||||

| Meza 2019 | Platelet Rich Fibrin (PRF) |

Case report | DPSCs | Autologous DPSCs isolated from extirpated autologous inflamed dental pulp were loaded on autologous PRF in lower premolar tooth with irreversible pulpitis for successful regeneration. | |||

| Ducret et al., 2019 | Fibrin–chitosan | In vitro | Enriching the fibrin-hydrogel with chitosan. | 10 mg/mL fibrinogen and 0.5% (w/w), 40% DA chitosan, formed a hydrogel at physiological pH (≈7.2), which was sufficiently fluid to preserve its injectability without affecting fibrin biocompatibility | DPSCs | Chitosan imparted antibacterial activity to fibrin hydrogel, reducing E. faecalis growth. The blending of chitosan in fibrin hydrogels did not affect the viability, proliferation and collagen-forming capacity of encapsulated DPSCs as compared to unmodified fibrin. |

|

| Mittal et al., 2019 | PRF | Clinical trial | PRF and collagen are better scaffolds than placentrex and chitosan for apexogenesis of immature necrotic permanent teeth. | ||||

| Bekhouche et al., 2020 | Fibrin | In vitro | Incorporation of clindamycin loaded Poly (D, L) Lactic Acid nanoparticles (CLIN-loaded PLA NPs). |

Fibrin hydrogel constituted a reservoir of CLIN-loaded PLA NPs inhibiting E. faecalis growth without affecting cell viability and function. | DPSCs | Fibrin hydrogels containing CLIN-loaded PLA NPs showed an antibacterial effect against E. faecalis and inhibited biofilm formation. DPSCs viability and type I collagen synthesis in cellularized hydrogels were similar to the unmodified groups. | |

| Renard et al., 2020 | Fibrin-chitosan | In vivo | Same formulation of fibrin–chitosan hydrogel as used by Ducret et al., 2019 | 40% DA chitosan incorporation in the fibrin hydrogel did not modify modify dental pulpi inflammatory/immune response and triggered polarization of pro-regenerative M2 macrophages. | In in vivo model of rat incisor pulpotomy, fibrin–chitosan hydrogels imparted a similar inflammatory response in the amputated pulp as unmodified fibrin. Both groups enhanced the polarization of pro-regenerative M2 macrophages. | ||

| Zhang et al., 2020 | Fibrin | In vitro | Fibrin hydrogel loaded with DPSCs-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs). | 2 mg/mL fibrinogen formed a hydrogel which was able to retain and preserve the activity of EVs. Forming the most extensive tubular network forming at an EVs concentration of 200 µg/mL | Co-culture of DPSCs and HUVECs | VEGF | Investigated hydrogels enhanced rapid neovascularization under starvation culture, increased deposition of collagen I, III, and IV, and promoted the release of VEGF. |

| Matrigel 3D | |||||||

| Mathieu et al., 2013 | Matrigel | In vitro | DPSCs | Encapsulating transforming growth factor beta1 (TGF-b1) and FGF-2 in a biodegradable Poly glycolide-co-lactide (PGLA) microsphere |

|||

| Ito et al., 2017 | Matrigel | In vivo | Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) | Nestin, DSPP | Pulp tissue regeneration was successfully achieved. | ||

| Sueyama et al., 2017 | Matrigel | In vivo | BMMSCs and endothelial cells (ECs). | DSPP, Nestin Bcl-2, Cxcl1, Cxcr2, VEGF |

The implantation of ECs with mesenchymal stem cells accelerated pulp tissue regeneration/healing and dentin bridge formation. | ||

| Gu et al., 2018 | Matrigel | In vivo | BMMSCs | M1-to-M2 transition of macrophages plays an important role in creating a favorable microenvironment necessary for pulp tissue regeneration. | |||

| Kaneko et al., 2019 | Matrigel | In vivo | BMMSCs nucleofected with pVectOZ-LacZ plasmid encoding β-galactosidase |

DSPP | BMMSCs could differentiate into cells involved in mineralized tissue formation in the functionally relevant region. | ||

| Keratin Hydrogel | |||||||

| Sharma et al., 2016 | Keratin hydrogel | In vitro | Highly branched interconnected porous micro-architecture with a maximum average pore size of 160 µm and minimum pore size of 25 µm. G′ > G″ indicates the elastic solid-like nature of the gel. After 3 months the degradation rate was 68%. |

odontoblast-like cells (MDPC-23) |

ALP, DMP-1 | Keratin enhanced proliferation and odontoblastic differentiation of odontoblast-like cells. Keratin hydrogels may be a potential scaffold for pulp–dentin regeneration. | |

| Sharma et al., 2016 | Keratin hydrogel | In vitro In vivo |

Highly branched interconnected porous micro-architecture with a maximum average pore size of 160 µm and minimum pore size of 25 µm. G′ > G′′ indicates the elastic solid-like nature of the gel. After 3 months the degradation rate was 68%. |

odontoblast-like cells (MDPC-23) and DPSCs |

Keratin hydrogel enhanced odontogenic differentiation of odontoblast-like cells and enhanced reparative dentin formation. | ||

| Sharma et al., 2017 | Keratin hydrogel | In vivo | Branched interconnected porous micro-architecture with average pore size 163.5 and porosity 82.8%. There was a gradual increase in G’ from 7% to 20% (w/v) gel concentration. The average contact angle was 35.5°. | Keratins hydrogel can be a source for biological treatment options for dentin–pulp complex. | |||

| Alginate Hydrogel | |||||||

| Dobie et al., 2002 | Alginate | In vitro | TGF- β1 or HCL acid-treatment of the hydrogels. | Alginate hydrogels are valuable for delivery of growth factors (GFs) (or agents to release endogenous GFs) to enhance reparative processes of dentin–pulp complex. | Alginate hydrogel acted as an efficient carrier for TGF- β1. Furthermore, acid treatment of the hydrogel aided in the release of TGF- β1 from dentin matrix. Alginate–TGF–β1 blends stimulated reactionary dentinogenic responses with increased predentin width. | ||

| Bhoj et al., 2015 | Alginate | In vitro | Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD)-modified alginate hydrogels, loaded with VEGF and FGF-2. | RGD–alginate matrix acted as pulp replacement, compatible with the DPSCs and HUVECs, and can deliver VEGF and FGF-2. | Co-culture of DPSCs and HUVECs | Combined addition of FGF and VEGF led to an increased proliferation of both DPSCs and HUVECs in the hydrogels. RGD-modified alginate can efficiently retain VEGF and FGF-2. | |

| Smith et al., 2015 | Alginate | In vitro | Alginate hydrogel doped with bovine dental pulp extracellular matrix (pECM). | 3D Alginate hydrogel doped with pECM formed 3D matrices. pECM provides additional signals for differentiation. |

Primary dental pulp cells | Induced differentiation in the mineralizing medium resulted in time-dependent mineral deposition at the periphery of the hydrogel. | |

| Verma et al., 2017 | Alginate–fibrin | In vivo | Oxidized alginate–fibrin hydrogel microbeads. | 7.5% oxidized alginate coupled with fibrinogen concentration of 0.1% enhanced microbead degradation, cell release, and proliferation. | DPSCs | Oxidized alginate–fibrin hydrogel microbeads encapsulating DPSCs showed similar regenerative potential to traditional revascularization protocol in ferret teeth. In both groups, the presence of residual bacteria affected root development. | |

| Athirasala et al., 2018 | Alginate | In vitro | Blending alginate hydrogels with soluble and insoluble fractions of the dentin matrix as a bioink for 3D printing. | Dentin matrix proteins preserve the natural cell-adhesive (RGD) and MMP-binding sites, which are lacking in unmodified alginate, that are important for viability, proliferation, and differentiation. | SCAP | ALP, Runt-related transcription factor -2 (RUNX2) | Alginate and insoluble dentin matrix (in 1:1 ratio) hydrogels bioink significantly enhanced odontogenic differentiation of SCAP under the effect of the soluble dentin molecules in the hydrogel. |

| Yu et al., 2019 | Alginate and gelatin hydrogels | In vitro | 3D bioprinted crosslinked composite alginate and gelatin hydrogels (4% and 20% by weight, respectively). | 3D printing accurately controls the interconnected porosity and pore diameter of the scaffold, and imitate natural cell tissue in vivo. | DPSCs | ALP, OCN, DSPP | 3D-printed alginate and gelatin hydrogels aqueous extracts are more suitable for the growth of DPSCs, and can better promote cell proliferation and differentiation. |

| Chitosan Hydrogel | |||||||

| Park et al., 2013 | Chitosan hydrogel | In vitro | N-acetylation of glycol chitosan |

Glycol chitosan (0.2 g) and acetic anhydride (0.87 g) were dissolved in 50 mL of a mixture of distilled water and methanol (50/50, v/v) degree of acetylation 90% pore size ranged from 5 to 40 mm. |

Human DPSCs | DSPP, DMP-1, ON, osteopontin |

Glycol chitin-based thermo-responsive hydrogel scaffold promoted the proliferation and odontogenic differentiation of human DPSCs. |

| El Ashiry et al., 2018 | Chitosan hydrogel | In vivo | Chitosan 1 g; 77% deacylation, high molecular weight, was dissolved in 2% acetic acid. |

DPSCs | DPSCs and GFs incorporated in chitosan hydrogel can regenerate pulp–dentin-like tissue in non-vital immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis in dogs. |

||

| Wu et al., 2019 | Chitosan hydrogel | In vitro | beta-sodium glycerophosphate added to chitosan (CS/β-GP). | viscosity: 200–400 m Pa·s 2% (w/v) chitosan solution 56% (w/v) beta-sodium glycerophosphate (β-GP) solution CS: β-GP is 5/L |

DPSCs | VEGF, ALP, OCN, Osterix, DSPP |

CS/β-GP hydrogel could release VEGF continually and promote odontogenic differentiation of DPSCs. |

| Zhu et al., 2019 | Chitosan hydrogel | In vitro | Ag-doped bioactive glass micro-size powder particles added to chitosan (Ag-BG/CS). | Ag-BG/CS pore diameter reaching around 60–120 μm. |

DPSCs | OCN, ALP, RUNX-2 |

Ag-BG/CS enhanced the odontogenic differentiation potential of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory-reacted dental pulp cells and expressed antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activity. |

| Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel | |||||||

| Chrepa et al., 2016 | Hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel | In vitro | SCAP/Restylane 1:10 concentration SCAP/Matrigel mixture at 1:1 concentration 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether; DVS, divinyl sulphone crosslinking agent |

SCAP | ALP, DSPP, DMP-1, MEPE gene | HA injectable hydrogel promoted SCAP survival, mineralization and differentiation into an odontoblastic phenotype. | |

| Yang et al., 2016 | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel | In vivo | HA crosslinked with 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether |

HA (1.5 × 106 Da) 1,4-Butanediol diglycidyl ether crosslinking agent HA concentration of 20 mg mL−1 gel particles of 0– 400 mm. |

Dental mesenchymal cells | HA is an injectable scaffold that can regenerate cartilage and dentin–pulp complex. | |

| Almeida et al., 2018 | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel | In vitro | Photo crosslinking of methacrylated HA incorporated with PL. | High molecular weight (1.5–1.8 MDa) HA 1% (w/v) HA solution (in distilled water) reacted with methacrylic anhydride (10 times molar excess) methacrylated disaccharides% was 10.9 ± 1.07% HA hydrogels incorporating 100% (v/v) PL Met-HA was dissolved at a concentration of 1.5% (w/v) in both of the PBS and PL photoinitiator solutions. |

Human DPSCs | ALP, collagen type I A 1 strand (COLIA1) | HA hydrogels incorporating PL increased the cellular metabolism and stimulate the mineralized matrix deposition by hDPSCs. |

| Silva et al., 2018 | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel | In vitro Ex vivo |

HA hydrogels incorporating cellulose nanocrystals and enriched with Platelet lysate (PL). | 1 wt. % ADH-HA, 1 wt. % a-HA, 0.125 to 0.5 wt. % a-CNCs in 50 v/v% PL solution. | Human DPSCs | HA hydrogel enabled human DPSCs survival and migration. | |

| Zhu et al., 2018 | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel | In vivo | Crosslinked HA hydrogel | Crosslinked HA gel (24 mg/mL) mixed with cells at 1:1–1:1.4 (v/v, i.e., gel/cells) ratio with final cell concentration of *2 · 107/mL 1,4-butanediol diglycidyl ether; DVS, divinyl sulphone crosslinking agent 9% |

DPSCs | Nestin, DSPP, DMP-1, Bone sialoprotein |

HA hydrogel regenerated pulp-like tissue with a layer of dentin-like tissue or osteodentin along the canal walls. |

| Niloy et al., 2020 | Hyaluronic acid hydrogel | In vitro | Converting sodium salt of HA into Tetrabutylammonium salt and subsequent conjugation of Aminoethyl methacrylate (AEMA) to HA backbone. | AEMA-HA macromers of two different molecular weights (18 kD and 270 kD) 1 g of H/100 mL deionized water, mixed with 12.5 g of ion exchange resin was converted from its hydrogen form to its TBA form AEMA hydrochloride (0.25 equivalent to HA repeat units) |

DPSCs | NANOG, SOX2 | HA hydrogels have great potential to mimic the in vivo 3D environment to maintain the native morphological property and stemness of DPSCs. |

| Agarose Hydrogel | |||||||

| Cao et al., 2016 | Agarose hydrogel | In vitro | Calcium chloride (CaCl 2) Agarose hydrogel | 1.0 g of Agarose powder, 1.9 g of CaCl 2 H20 |

Agarose hydrogel promoted occlusion of dentinal tubules and formation of enamel prisms-like tissue on human dentin surface. | ||

| Cellulose Hydrogel | |||||||

| Teti et al., 2015 | Cellulose hydrogel | In vitro | Hydroxyapatite was loaded inside CMC hydrogel | Degree of carboxymethylation of 95% (CMC) (average MW 700 KDa) | DPSCs | ALP, RUNX2, COL-IA1, SPARC, DMP-1, DSPP |

CMC–hydroxyapatite hydrogel up regulated the osteogenic and odontogenic markers expression and promoted DPSCs adhesion and viability. |

| Aubeux et al., 2016 | Cellulose hydrogel | In vitro | Silanes grafted along the hydroxy-propyl-methyl-cellulose chains. | nanoporous macromolecular structure. Pores have an average diameter of 10 nm | TGF-b1 | Cellulose hydrogel enhanced non-collagenous matrix proteins release from smashed dentin powder. | |

| Iftikhar et al., 2020 | Cellulose hydrogel | In vitro | The surface area, average pore size and particle size of BAG (45S5 Bioglass®) were 65m2/g 5.7 nm, and 92 nm, respectively. |

MC3T3-E1 cells differentiated into osteoblasts and osteocytes. | The prepared injectable bioactive glass, hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose (HPMC) and Pluronic F127 was biocompatible in an in vitro system and has the ability to regenerate dentin. | ||

| Extracellular Matrix Hydrogel | |||||||

| Chatzistavrou et al., 2014 | Extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogel | In vitro | silver-doped bioactive glass (Ag-BG) incorporated into ECM | Ag-BG powder form with particle size < 35μm. ECM concentration of 10 mg/mL ECM60/Ag-BG40, ECM50/Ag-BG50, ECM30/Ag-BG70 weight ratio. |

DPSCs | Ag-BG/ECM presented enhanced regenerative properties and anti-bacterial action. | |

| Wang et al., 2015 | ECM hydrogel | In vivo In vitro |

silver-doped bioactive glass (Ag-BG) incorporated into ECM | Ag-BG powder form with particle size < 35μm. ECM pepsin digest stock solutions of 10 mg ECM/mL (dry weight) Ag-BG: ECM = 1:1 in wt. %. |

DPSCs | Ag-BG/ECM showed antibacterial property, induced dental pulp cells proliferation and differentiation. The in vivo results supported the potential use of Ag-BG/ECM as an injectable material for the restoration of lesions involving pulp injury. | |

| Li et al., 2020 | ECM hydrogel | In vitro | Pre-gel solution was diluted into 0.75% w/v and 0.25% w/v. | Human DPSCs | DSPP, DMP-1 | decellularized matrix hydrogel derived from human dental pulp effectively contributed to promoting human DPSCs proliferation, migration, and induced multi-directional differentiation. |

|

| Holiel et al., 2020 | ECM hydrogel | Clinical trial | Human treated dentin matrix hydrogel was dispersed in sodium alginate solution | Particle sized powder (range 350–500 μm) 5% (w/v) of sodium alginate 0.125 g of sterile human treated dentin matrix was dispersed in the sodium alginate solution with a mass ratio of 1:1 |

Treated dentin matrix hydrogel attained dentin regeneration and conservation of pulp vitality. | ||

Table 2. Synthetic hydrogels.

| Synthetic Hydrogels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Hydrogel Used | Type of Study | Hydrogel Modification | Hydrogel Properties | Cells Used | Upregulated Biological Molecules | Outcomes |

| PLA Based Polymers | |||||||

| Shiehzadeh et al., 2014 | Polylactic polyglycolic acid–polyethylene glycol (PLGA-PEG) | Clinical trial | Stem/progenitor cells from the apical dental papilla (SCAP) | Biologic approach can provide a favorable environment for clinical regeneration of dental and paradental tissues. | |||

| Synthetic Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogel (Peptide Amphiphiles) | |||||||

| Galler et al., 2008 | Synthetic peptide amphiphiles | In vitro | Peptide amphiphiles involves arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) and an enzyme-cleavable site | Peptide was dissolved at pH 7.0 to attain stock solution of 2% by weight | stem/progenitor cells of exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) and dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) | The hydrogels are easy to handle and can be introduced into small defects, therefore this novel system might be suitable for dental tissue regeneration. | |

| Multi Domain Self-Assembling Peptide (MDP) Hydrogel | |||||||

| Galler et al., 2011 | In vivo | MDP functionalized with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) via heparin binding | DPSCs | In tooth slices, implanted hydrogel degraded and replaced by a vascularized connective tissue similar to dental pulp. Pretreatment of the tooth cylinders with NoOCl showed resorption lacunae. With NaOCl followed by ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), DPSCs differentiated into odontoblasts-like cells intimately associated with the dentin surface. | |||

| Galler et al., 2012 | MDP | In vivo | MDP functionalized with TGF-β1, FGF-2, and VEGF via heparin binding | DPSCs | Hydrogels implanted into the backs of immunocompromised mice resulted in the formation of vascularized soft connective tissue similar to dental pulp. | ||

| Colombo et al., 2020 | MPD hydrogel | In vitro | SHED | Decellularized and lyophilized MDP produced a biomaterial containing anti-inflammatory bioactive molecules that can provide a tool to reduce pulpal inflammation to promote dentin–pulp complex regeneration. | |||

| RADA16-I Hydrogels Self-Assembling Peptide | |||||||

| Cavalcanti et al., 2013 | A commercial self-assembling peptide | In vitro | 0.2% Puramatrix™ (1% w/v) |

DPSCs | Dentin matrix protein (DMP)-1, Dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP) | DPSCs expressed DMP-1 and DSPP after 21 days culturing in dentin slices containing PuramatrixTM. The surviving dentin provided signaling molecules to cells suspended in PuramatrixTM. | |

| Rosa et al., 2013 | A commercial self-assembling peptide | In vitro In vivo |

0.2% Puramatrix™ (1% w/v) | SHED | DMP-I, DSPP, matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein (MEPE) | Upon mixing SHED with Puramatrix™ hydrogel for 7 days and injecting the construct into roots of human premolars, the cells survived and expressed (DMP-I, DSPP, MEPE) in vitro. Pulp-like tissue with odontoblasts able to form neo-dentinal tubules was observed in vivo. | |

| Dissanayaka et al., 2015 | A commercial self-assembling peptide | In vitro In vivo |

Among different Puramatrix™ (1% w/v) concentrations, 0.15% was the optimal. | DPSCs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | PuramatrixTM enhanced in vitro cell survival, migration and capillary formation. Co-cultured groups on PuramatrixTM exhibited more extracellular matrix, mineralization and vascularization than DPSC-monocultures in vivo. | ||

| Nguyen et al., 2018 | RADA16-I | In vitro | incorporation of dentonin sequence | Ribbonlike nanofibers with height (∼2 nm) and width (∼14 nm) | DPSCs | The self-assembled peptide platform holds promise for guided dentinogenesis. | |

| Huang, 2020 | RADA16-I | In vitro | Low concentration (0.125%, 0.25%) caused higher cell proliferation rate than high concentration (0.5%, 0.75%, 1%) | DPSCs and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | DSPP, DMP-1, Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), osteocalcin (OCN) | The co-culture groups promoted odontoblastic differentiation, proliferation and mineralization. | |

| Mu et al., 2020 | RADA16-I | In vitro | incorporated with stem cell factor | 100 ng/mL was the optimum concentration of the stem cell factor. Nanofibers and pores diameter were (10–30nm and 5–200nm, respectively) |

DPSCs and HUVECs | Stem cell factor incorporate RADA16-I holds promise for guided pulp regeneration. | |

| Zhu et al., 2019 | Cells were cultured on Matrigel before being loaded on commercial self-assembling peptide | In vitro In vivo |

300 μL 1% Puramatrix™ (1% w/v) | DPSCs overexpressing Stromal derived factor-(SDF)-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) | SDF-1, VEGF | Combination of VEGF- and SDF-1-overexpressing DPSCs cultured on Matrigel before being loaded on PuramatrixTM enhanced the area of vascularized dental pulp regeneration in vivo. | |

| Xia et al., 2020 | Self-assembling peptide | In vitro In vivo |

incorporation of RGD, VEGF mimetic peptide sequence | The nanofibers’ diameters of functionalized peptide were thicker than pure RAD. that the stiffness of RAD/ RGD-mimicking peptide (PRG)/ VEGF-mimicking peptide: (KLT) hydrogels was greater than the others |

DPSCs and HUVECs | Modified self-assembling peptide hydrogel effectively stimulated stem cells angiogenic and odontogenic differentiation in vitro and dentin–pulp complex regeneration in vivo. | |

| Poly-dimethylsiloxane Hydrogel | |||||||

| Liu et al., 2017 | Poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) | In vitro | Stiffness for 10:1, 20:1, 30:1 and 40:1 was 135, 54, 16 and 1.4 kPa and roughness was 55.67, 53.38, 50.95, and from 47.32 to 42.50nm. Water contact angle was 65°. | DPSCs | osteopontin (OPN), runt-related transcription factor (RUNX)-2, Bone morphogenetic protein | Osteogenic and odontogenic markers were positively correlated to the substrate stiffness. The results revealed that the mechanical properties promoted the function of DPSCs related to the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. | |

| Poly-N-isopropylacrylamide Gel | |||||||

| Itoh et al., 2018 | Poly-N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAm) | In vitro In vivo |

NIPAAm crosslinked by PEG-DMA | Decrease in wet weight from 1 to 0.18 at 508 C. Change in surface area from 1 (258 C) to 0.62 (508 C) within 1 h. High wettability. | DPSCs | DSPP in the outer cell layer, Nanog in the center of the constructs | DPSCs in the outer layer of the constructs differentiated into odontoblast-like cells, while DPSCs in the inner layer maintained their stemness. Pulp-like tissues rich in blood vessels were formed in vivo. |

| Polyethylene Glycol | |||||||

| Komabayashi et al., 2013 | PEG | In vitro | PEG–maleate–citrate (PEGMC) (45% w/v), acrylic acid (AA) crosslinker (5% w/v), 2,2′-Azobis (2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH) photo-initiator (0.1% w/v), | Optimum cell viability with exposure time of 30 s with a monomer and AAPH concentration of 0.088% and up to 1%, respectively | L929 cells | Cell viability remained up to 80% after 6 h. Controlled Ca2+ release was attained. The viscosity and injection ability into plastic root canal blocks were confirmed in a dental model. | |

| VitroGel 3D | |||||||

| Xiao et al., 2019 | Vitrogel | In vitro In vivo |

VitroGel diluted with deionized water 1:2. | SCAP | RUNX-2,DMP-1, DSPP, OCN | VitroGel 3D promoted SCAP proliferation and differentiation. SDFr-1α and BMP-2 co-treatment induced odontogenic differentiation of human SCAP cultured in the VitroGel 3D in vitro and in vivo |

|

Table 3. Hybrid hydrogels.

| Hybrid Hydrogels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Hydrogel Used | Type of Study | Hydrogel Modification | Hydrogel Properties |

Cells Used | Upregulated Biological Molecules | Outcomes |

| Alginate/laponite hydrogel | |||||||

| Zhang et al., 2020 | Alginate/laponite hydrogel | In vitro In vivo |

Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) modified alginate and nano-silicate laponite hydrogel microspheres, encapsulating human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). |

The RGD-Alg had 55% degradation rate and the RGD- alginate/laponite exhibited 45% while pure alginate degraded only 20% after 28 days. | DPSCs | Alkaline phosphatase (ALP), Dentine matrix protein 1 (DMP-1), collagen I (Col-I) | Hybrid RGD modified alginate/laponite hydrogel microspheres has a promising potential in vascularized dental pulp regeneration. |

| PEG-modified natural polymers | |||||||

| Galler et al., 2011 | PEGylated fibrin | In vitro In vivo |

PEGylated fibrinogen with added thrombin. | Carboxylated N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide-active ester polyethylene glycol (PEG) (MW = 3400 Da) added to 40 mg/mL of bovine fibrinogen in TRIS- saline at a molar ratio of 10:1. Equal volume of thrombin (200 U/mL in 40 mM CaCl2) was added | Stem cells isolated from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED), DPSCs, periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs), bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMMSCs) |

Col I, Col III, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2), bone Sialoprotein (BSP), osteocalcin (OCN), runt-related transcription factor -2 (RUNX2), dentin sialophosphoprotein (DSPP), DMP-1 | ALP activity and osteoblastic and odontoblast differentiation genes were higher in dental stem cells than BMMSCs. SHED and PDLSCs exhibited high expression of collagen, while DPSCs and PDLSCs expressed high levels of differentiation late markers. In vivo, fibrin matrix degraded and replaced by vascularized connective tissue. |

| Lu et al., 2015 | PEG fibrinogen | In vitro | PEG fibrinogen with variable amounts of polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) | Increase of PEGDA crosslinker allows for higher modulus but longer times of crosslinking and less swelling ratio | DPSCs | Col I, DSPP, DMP-1, OCN | Odontogenic genes expressions and mineralization were correlated to the hydrogel crosslinking degree and matrix stiffness |

| Jones et al., 2016 | HyStem-C is a commercial hydrogel hyaluronic acid (HA)- PEGDA -gelatin | In vitro | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate with an added disulfide bond (PEGSSDA) with an added disulfide bond. | Hydrogel gelation time decreased as the PEGSSDA crosslinker concentration (w/v) increased from (0.5% to 8.0%) | DPSCs | The PEGSSDA-HA-Gn was biocompatible with human DPSCs. Cell proliferation and spreading increased considerably with adding fibronectin to PEGDA-HA-Gn hydrogels. | |

| Feng et al., 2020 | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate\sodium alginate (PEGDA/SA) | In vitro In vivo |

PEGDA/SA loaded basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (PEGDA/SA-bFGF) | DPSCs | Reduction of mass ratio of PEGDA/SA to 20:1 ~ 15:1 resulted in the formation of a well-organized pulp structure after implantation | ||

Table 4. Comparing natural and synthetic hydrogels.

| Comparing Natural and Synthetic Hydrogels | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galler et al., 2018 | - PEG - Self-assembling peptide (SAPbio) and Puramatrix™) |

In vitro In vivo |

- PEG was modified to be chemically cured (PEGchem) or light-cured (PEGlight), - Biomimetic hydrogels (PEGbio) modified by cell adhesion motif and MMP-2. - Self-assembling peptide (SAPbio) modified by cell adhesion motif and MMP-2. |

DPSCs | TGF-β1 | In vitro viability was higher in natural materials. Scaffold degradation, odontoblast-like cell differentiation, tissue formation and vascularization were higher in natural materials in vivo. |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polym12122935

References

- Drury, J.L.; Mooney, D.J. Hydrogels for tissue engineering: Scaffold design variables and applications. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4337–4351.

- Kwon, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Hwang, Y.C.; Rosa, V.; Lee, K.W.; Min, K.S. Behaviour of human dental pulp cells cultured in a collagen hydrogel scaffold cross-linked with cinnamaldehyde. Int. Endod. J. 2017, 50, 58–66.

- Pankajakshan, D.; Voytik-Harbin, S.L.; Nor, J.E.; Bottino, M.C. Injectable Highly Tunable Oligomeric Collagen Matrices for Dental Tissue Regeneration. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 859–868.

- Bhatnagar, D.; Bherwani, A.K.; Simon, M.; Rafailovich, M.H. Biomineralization on enzymatically cross-linked gelatin hydrogels in the absence of dexamethasone. Dent. Mater. 2015, 3, 5210–5219.

- Miyazawa, A.; Matsuno, T.; Asano, K.; Tabata, Y.; Satoh, T. Controlled release of simvastatin from biodegradable hydrogels promotes odontoblastic differentiation. Dent. Mater. J. 2015, 34, 466–474.

- Khayat, A.; Monteiro, N.; Smith, E.; Pagni, S.; Zhang, W.; Khademhosseini, A.; Yelick, P.C. GelMA-encapsulated hDPSCs and HUVECs for dental pulp regeneration. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 192–199.

- Park, J.H.; Gillispie, G.J.; Copus, J.S.; Zhang, W.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J.; Yelick, P.C.; Lee, S.J. The effect of BMP-mimetic peptide tethering bioinks on the differentiation of dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in 3D bioprinted dental constructs. Biofabrication 2020, 12, 35029.

- Galler, K.M.; Cavender, A.C.; Koeklue, U.; Suggs, L.J.; Schmalz, G.; D’Souza, R.N. Bioengineering of dental stem cells in a PEGylated fibrin gel. Regen. Med. 2011, 6, 191–200.

- Jang, J.-H.; Moon, J.-H.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.-Y. Pulp regeneration with hemostatic matrices as a scaffold in an immature tooth minipig model. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12536.

- Athirasala, A.; Lins, F.; Tahayeri, A.; Hinds, M.; Smith, A.J.; Sedgley, C.; Ferracane, J.; Bertassoni, L.E. A Novel Strategy to Engineer Pre-Vascularized Full-Length Dental Pulp-like Tissue Constructs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3323.

- Ajay Sharma, L.; Ali, M.A.; Love, R.M.; Wilson, M.J.; Dias, G.J. Novel keratin preparation supports growth and differentiation of odontoblast-like cells. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 471–482.

- Ajay Sharma, L. Wool-derived keratin hydrogel as a potential scaffold for pulp-dentine regeneration: An in vitro and in vivo study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2016.

- Zhang, S.; Thiebes, A.L.; Kreimendahl, F.; Ruetten, S.; Buhl, E.M.; Wolf, M.; Jockenhoevel, S.; Apel, C. Extracellular Vesicles-Loaded Fibrin Gel Supports Rapid Neovascularization for Dental Pulp Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4226.

- Ha, M.; Athirasala, A.; Tahayeri, A.; Menezes, P.P.; Bertassoni, L.E. Micropatterned hydrogels and cell alignment enhance the odontogenic potential of stem cells from apical papilla in-vitro. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 88–96.

- Xiao, M.; Qiu, J.; Kuang, R.; Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; Yu, Q. Synergistic effects of stromal cell-derived factor-1α and bone morphogenetic protein-2 treatment on odontogenic differentiation of human stem cells from apical papilla cultured in the VitroGel 3D system. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 378, 207–220.

- Galler, K.M.; Cavender, A.; Yuwono, V.; Dong, H.; Shi, S.; Schmalz, G.; Hartgerink, J.D.; D’Souza, R.N. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofibers as a scaffold for dental stem cells. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008, 14, 2051–2058.

- Colombo, J.S.; Jia, S.; D’Souza, R.N. Modeling Hypoxia Induced Factors to Treat Pulpal Inflammation and Drive Regeneration. J. Endod. 2020, 46, S19–S25.

- Rosa, V.; Zhang, Z.; Grande, R.; Nör, J. Dental pulp tissue engineering in full-length human root canals. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 970–975.

- Ito, T.; Kaneko, T.; Sueyama, Y.; Kaneko, R.; Okiji, T. Dental pulp tissue engineering of pulpotomized rat molars with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Odontology 2017, 105, 392–397.

- Sueyama, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Ito, T.; Kaneko, R.; Okiji, T. Implantation of Endothelial Cells with Mesenchymal Stem Cells Accelerates Dental Pulp Tissue Regeneration/Healing in Pulpotomized Rat Molars. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 943–948.

- Gu, B.; Kaneko, T.; Zaw, S.Y.M.; Sone, P.P.; Murano, H.; Sueyama, Y.; Zaw, Z.C.T.; Okiji, T. Macrophage populations show an M1-to-M2 transition in an experimental model of coronal pulp tissue engineering with mesenchymal stem cells. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 52, 504–514.

- Kaneko, T.; Sone, P.P.; Zaw, S.Y.M.; Sueyama, Y.; Zaw, Z.C.T.; Okada, Y.; Murano, H.; Gu, B.; Okiji, T. In vivo fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells implanted into rat pulpotomized molars. Stem. Cell Res. 2019, 38, 101457.

- Smith, J.G.; Smith, A.J.; Shelton, R.M.; Cooper, P.R. Dental Pulp Cell Behavior in Biomimetic Environments. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 1552–1559.

- Bekhouche, M.; Bolon, M.; Charriaud, F.; Lamrayah, M.; Da Costa, D.; Primard, C.; Costantini, A.; Pasdeloup, M.; Gobert, S.; Mallein-Gerin, F. Development of an antibacterial nanocomposite hydrogel for human dental pulp engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 8422–8432.

- Bhoj, M.; Zhang, C.; Green, D.W. A First Step in De Novo Synthesis of a Living Pulp Tissue Replacement Using Dental Pulp MSCs and Tissue Growth Factors, Encapsulated within a Bioinspired Alginate Hydrogel. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1100–1107.

- Kikuchi, N.; Kitamura, C.; Morotomi, T.; Inuyama, Y.; Ishimatsu, H.; Tabata, Y.; Nishihara, T.; Terashita, M. Formation of dentin-like particles in dentin defects above exposed pulp by controlled release of fibroblast growth factor 2 from gelatin hydrogels. J. Endod. 2007, 33, 1198–1202.

- Nagy, M.M.; Tawfik, H.E.; Hashem, A.A.R.; Abu-Seida, A.M. Regenerative potential of immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulps after different regenerative protocols. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 192–198.

- Dobie, K.; Smith, G.; Sloan, A.J.; Smith, A.J. Effects of alginate hydrogels and TGF-β1 on human dental pulp repair in vitro. Connect. Tissue Res. 2002, 43, 387–390.

- Mu, X.; Shi, L.; Pan, S.; He, L.; Niu, Y.; Wang, X. A Customized Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogel-Wrapped Stem Cell Factor Targeting Pulp Regeneration Rich in Vascular-Like Structures. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16568–16574.

- Nguyen, P.K.; Gao, W.; Patel, S.D.; Siddiqui, Z.; Weiner, S.; Shimizu, E.; Sarkar, B.; Kumar, V.A. Self-assembly of a dentinogenic peptide hydrogel. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5980–5987.

- Xia, K.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Q. RGD-and VEGF-Mimetic Peptide Epitope-Functionalized Self-Assembling Peptide Hydrogels Promote Dentin-Pulp Complex Regeneration. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6631.

- Tabata, Y.; Nagano, A.; Ikada, Y. Biodegradation of Hydrogel Carrier Incorporating Fibroblast Growth Factor. Tissue Eng. 1999, 5, 127–138.

- Ishihara, M.; Obara, K.; Nakamura, S.; Fujita, M.; Masuoka, K.; Kanatani, Y.; Takase, B.; Hattori, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Ishihara, M. Chitosan hydrogel as a drug delivery carrier to control angiogenesis. J. Artif. Organs 2006, 9, 8–16.