Halitosis, also known as fetor ex ore, bad breath or oral malodor, is a common disorder meaning unpleasant

smell from the mouth.

- Halitosis

- Malodor

- Volatile sulfur compounds

- hydrogen sulfide

- microbiota

- Fusobacterium

- Porphyromonas

- Prevotella

- periodontitis

- carcinogenesis

1. Definition

Halitosis is a common problem that manifests as an unpleasant and disgusting odor emanating from the mouth [1]. Malodor is mainly caused by putrefactive actions of microorganisms on endogenous or exogenous proteins and peptides. Oral malodor is an embarrassing condition that affects a large percentage of the human population. This condition often results in nervousness, humiliation, and social difficulties, such as the inability to approach people and speak to them [2–6].

2. Introduction

Halitosis experiences from about 15% to 60% of the human population worldwide [7–12]. Halitosis can be divided into extra-oral halitosis (EOH) and intra-oral halitosis (IOH) [2,3,5].

The factors that increase the likelihood of halitosis include periodontal diseases, dry mouth, smoking, alcohol consumption, dietary habits, diabetes, and obesity. Halitosis can also be affected by the general hygiene of the body (i.e., dehydration, starvation, and high physical exertion), advanced age, bleeding gums, decreased brushing frequency, but also by stress [3,13–16]. Produced during stress, catecholamines and cortisol increased hydrogen sulfide production by sub-gingival anaerobic bacteria [17]. The medications which can cause extra-oral halitosis were categorized into 10 groups: acid reducers, aminothiols, anticholinergics, antidepressants, antifungals, antihistamines and steroids, antispasmodics, chemotherapeutic agents, dietary supplements, and organosulfur substances [18].

More and more patients are struggling with bad breath and report this problem to their primary care practitioner for diagnosis and management [19,20]. However, many physicians, dentists, and biologists have insufficient knowledge regarding the cause and biochemistry of this disease.

3. Classifications of Halitosis

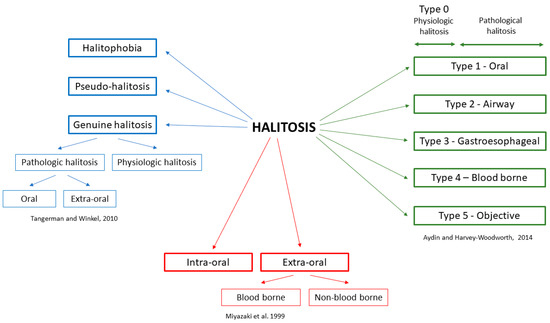

In the literature, mainly three classifications of halitosis are used, described by Miyazaki et al., 1999 [21], Tangerman and Winkel in 2010 [22], and Aydin and Harvey-Woodworth in 2014 [23] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classifications of halitosis [21–24].

Miyazaki et al. divided halitosis as intra-oral (IOH) and extra-oral (EOH) [21]. Extra-oral halitosis can be of bloodborne or non-bloodborne origin and covers about 5–10% of all halitosis [22]. Bloodborne-related causes include diabetes metabolic disorders, kidney and liver diseases, and certain drugs and food. Non-bloodborne-related causes include respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases. Meanwhile, pathological conditions in the oral cavity are responsible for 80–90% of IOH [2,3,25]. Both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria can be responsible for IOH. These microorganisms tend to produce foul-smelling, sulfur-containing gases called volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) [23,26].

In the classification of Tangerman and Winkel [22], halitosis is classified as genuine and delusional. Delusional halitosis (monosymptomatic hypochondriasis; imaginary halitosis) is a condition in which patients believe that their breath is smelly and offensive. The social pressure of having fresh smelling breath increases the number of people that are preoccupied with this condition. However, the perception of oral malodor does not always reflect actual clinical oral malodor [27]. Self-perceived halitosis was found to be more prevalent amongst males, particularly smokers, compared to females. However, there are no statistical differences when comparing with different age groups [28]. Genuine halitosis is further subdivided into physiological and pathological halitosis. Physiological halitosis (foul morning breath, morning halitosis) is caused by saliva retention, as well as the putrefaction of entrapped food particles. Meanwhile, intra- and extra-oral causes are responsible for pathological halitosis [3,4,19].

Aydin and Harvey-Woodworth divided pathologic halitosis into five types: Type 1 (oral), Type 2 (airway), Type 3 (gastroesophageal), Type 4 (blood-borne) and Type 5 (subjective). Moreover, it is Type 0 halitosis (physiologic odor), which can be a connection of the physiologic contributions of oral, airway, gastroesophageal, blood-borne, and subjective halitosis. Any combination of the above types can be present in every healthy person [23].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm9082484