Destination image and city branding are accumulating a growing body of knowledge in urban studies and tourism literature. Although several visitor destination image models have been proposed, the most prevalent in Asia remains the comprehensive destination image model. This is the first research to test the applicability of this model beyond the United States and with international (rather than domestic) visitors. Jakarta is chosen as the geographical test area for this study, which incorporates structural equation modeling on a data sample of international leisure visitors in Jakarta. The findings indicate that the destination image model could be generalized beyond the US and applied to Jakarta. This study finds that tourism policymakers in Jakarta should focus on promoting the friendliness of local residents and improving the city’s cleanliness, as these are the two most positive and negative perceptions. Overall, this study showed that a unique destination image—a largely under-researched topic in place branding—is a variable that should be considered when formulating the overall place image of city destinations around the world.

- destination image

- Indonesia

- intentions

- Jakarta

- LISREL

- structural equation modeling

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.1.1. Demographics, Origins, and Lengths of Stay

2.1.2. Cognitive Images

| Cognitive Image Items | Median Scores (n = 311) |

|---|---|

| Easy access to the area (Q1) | 4 |

| Restful and relaxing atmosphere (Q2) | 3 |

| Reasonable cost of hotels/restaurants (Q3) | 4 |

| Reasonable cost of shopping centers (Q4) | 3 |

| Beautiful scenery/natural wonders (Q5) | 3 |

| Lots of open space (Q6) | 3 |

| Friendly local people (Q7) | 5 |

| Delicious local cuisine (Q8) | 4 |

| Great state/theme parks (Q9) | 3 |

| Good place for children/family (Q10) | 3 |

| Availability of tourist welcome centers (Q11) | 3 |

| Good weather (Q12) | 4 |

| Interesting cultural events/festivals (Q13) | 3 |

| Good shopping facilities (Q14) | 4 |

| Clean/unspoiled environment (Q15) | 2 |

| Good infrastructure (Q16) | 3 |

| Availability of travel information (Q17) | 3 |

| A wide choice of accommodations (Q18) | 4 |

| Safe and secure environment (Q19) | 4 |

| A wide variety of entertainment (Q20) | 3 |

| Great nightlife (Q21) | 3 |

| Numerous water sports (Q22) | 3 |

| A wide variety of outdoor activities (Q23) | 3 |

| Lots of adventurous activities (Q24) | 3 |

| Availability of facilities for golfing/tennis (Q25) | 3 |

| Native Indonesian culture (Q26) | 4 |

| Rich historic and cultural sites (Q27) | 4 |

2.1.3. Unique Images

2.1.4. Affective Images

2.1.5. Overall Image of Jakarta

2.1.6. Future Intentions

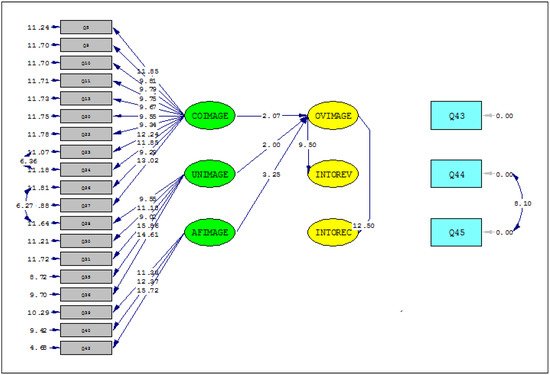

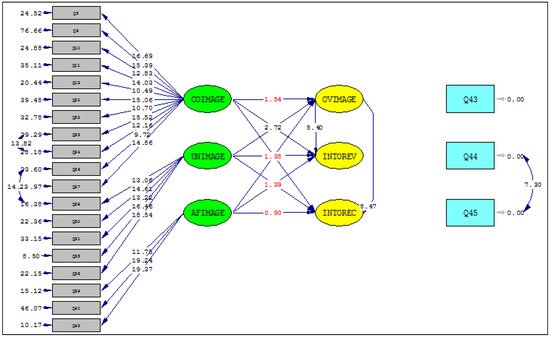

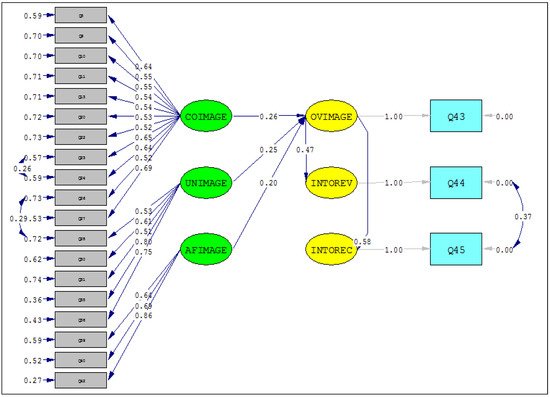

2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.2.1. Validity and Reliability Tests

| Image Items | Cognitive | Unique | Affective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beautiful scenery/natural wonders (Q5) | 0.64 | ||

| Great state/theme parks (Q9) | 0.55 | ||

| Good place for children/family (Q10) | 0.55 | ||

| Availability of tourist welcome centers (Q11) | 0.54 | ||

| Interesting cultural events/festivals (Q13) | 0.54 | ||

| A wide variety of entertainment (Q20) | 0.53 | ||

| Numerous water sports (Q22) | 0.52 | ||

| A wide variety of outdoor activities (Q23) | 0.65 | ||

| Lots of adventurous activities (Q24) | 0.64 | ||

| Native Indonesian culture (Q26) | 0.52 | ||

| Rich historic and cultural sites (Q27) | 0.69 | ||

| Native Indonesian cultures (Q28) | 0.53 | ||

| Wonderful scenery and natural wonders (Q30) | 0.61 | ||

| Relaxing spas (Q31) | 0.51 | ||

| Lots of tourist attractions (Q35) | 0.80 | ||

| Rich cultural/historical/heritage sites (Q36) | 0.75 | ||

| Pleasing (Q39) | 0.64 | ||

| Arousing (Q40) | 0.69 | ||

| Exciting (Q42) | 0.86 |

| Goodness of Fit Tests | Statistics |

|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.076 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.93 |

| Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.95 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.95 |

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.95 |

| Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.92 |

2.2.2. Goodness of Fit Tests

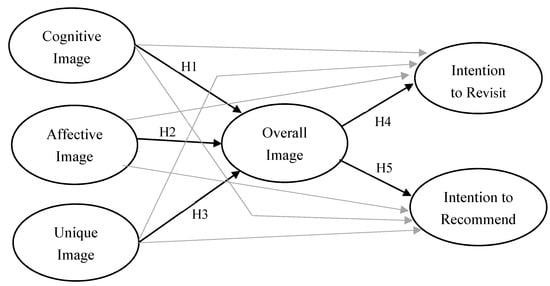

2.3. Structural Equation Modeling

2.4. Hypotheses Tests

3. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13137434

References

- Lucarelli, A.; Berg, P.O. City branding: A state-of-the-art review of the research domain. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2011, 4, 9–27.

- Degen, M.; García, M. The transformation of the “Barcelona model”: An analysis of culture, urban regeneration and governance. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 1022–1038.

- Eshuis, J.; Edwards, A. Branding the city: The democratic legitimacy of a new mode of governance. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 1066–1082.

- Ginesta, X.; de San Eugenio, J. Rethinking Place Branding from a Political Perspective: Urban Governance, Public Diplomacy, and Sustainable Policy Making. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 632–649.

- Sevin, H.E. Understanding cities through city brands: City branding as a social and semantic network. Cities 2014, 38, 47–56.

- Lu, H.; Ma, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, P. Exploring the impact of factors influencing case selection in the place branding literature from 2014 to 2018. J. Urban Aff. 2020.

- Ma, W.; Schraven, D.; de Bruijne, M.; De Jong, M.; Lu, H. Tracing the origins of place branding research: A bibliometric study of concepts in use (1980–2018). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2999.

- Kavaratzis, M. From city marketing to city branding: Towards a theoretical framework for developing city brands. Place Branding 2004, 1, 58–73.

- Gilboa, S.; Jaffe, E.D.; Vianelli, D.; Pastore, A.; Herstein, R. A summated rating scale for measuring city image. Cities 2015, 44, 50–59.

- Hanna, S.; Rowley, J.; Keegan, B. Place and Destination Branding: A Review and Conceptual Mapping of the Domain. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020.

- Evans, G. Hard-branding the cultural city—From Prado to Prada. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 417–440.

- Hollands, R.; Chatterton, P. Producing nightlife in the new urban entertainment economy: Corporatization, branding and market segmentation. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 361–385.

- Richards, G.; Wilson, J. The impact of cultural events on city image: Rotterdam, cultural capital of Europe 2001. Urban Stud. 2004, 41, 1931–1951.

- Garcia, J.A.; Gomez, M.; Molina, A. A destination-branding model: An empirical analysis based on stakeholders. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 646–661.

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Gázquez-Abad, J.C. Destination branding: Opportunities and new challenges. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100453.

- Hunt, J.D. Image as a factor in tourism development. J. Travel Res. 1975, 13, 1–7.

- Hosany, S.; Ekinci, Y.; Uysal, M. Destination image and destination personality: An application of branding theories to tourism places. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 638–642.

- Ashworth, G.J.; Voogd, H. Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Echtner, C.M.; Ritchie, J.R.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 1991, 14, 37–48.

- Siemiatycki, M. Message in a metro: Building urban rail infrastructure and image in Delhi, India. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2006, 30, 277–292.

- Byon, K.; Zhang, J. Development of a scale measuring destination image. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2009, 28, 508–532.

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.X. City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing. Cities 2009, 26, 245–254.

- Kislali, H.; Kavaratzis, M.; Saren, M. Destination image formation: Towards a holistic approach. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 266–276.

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476.

- Alcaniz, E.B.; Garcia, I.S.; Blas, S.S. Relationships among residents’ image, evaluation of the stay and post-purchase behavior. J. Vacat. Mark. 2005, 11, 291–302.

- Nunnaly, J. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978.

- Jöreskog, K.; Sörbom, D. LISREL 8.0: Structural Equation Modeling with SIMPLIS Command Language; Scientific Software International: Lincolnwood, IL, USA, 1993.

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60.

- Ullman, J.B. Structural equation modeling. In Using Multivariate Statistics; Tabachnick, B.G., Fidell, L.S., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 653–771.

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Needham Height, MA, USA, 2007.

- Wheaton, B.; Muthén, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136.

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149.

- Stern, E.; Krakover, S. The formation of a composite urban image. Geogr. Anal. 1993, 25, 130–146.

- Sarjono, H.; Julianita, W. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM); Salemba Empat: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015; pp. 222–224.