Human herpesviruses (HHVs): herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 (HSV-1) and 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), HHV-6, HHV-7, and HHV-8, are known to be part of a family of DNA viruses that cause several diseases in humans. In clinical practice of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the complication of CMV enterocolitis, which is caused by CMV reactivation under disruption of intestinal barrier function, inflammation, or strong immunosuppressive therapy, is well known to affect the prognosis of disease. However, the relationship between other HHVs and IBD remains unclear.

- human herpesviruses

- herpes simplex virus

- varicella-zoster virus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- cytomegalovirus

- inflammatory bowel disease

- ulcerative colitis

- Crohn’s disease

1. Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which are chronic and relapsing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), have been known to be complex multifactorial diseases, involving not only host factors, such as genetic factors, mucosal barrier dysfunction, and altered immune response, but also environmental factors, including infectious agents [1,2]. Recent papers have shown that alteration in the enteric virome could play a role in IBD pathogenesis [3,4]. The interactions between certain enteric viruses and Paneth cells could lead to the activation of the innate immune pathway and inflammatory immune response in IBD [5]. It has been demonstrated that enteric viruses could also infect macrophages stimulating the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interferon (IFN)-γ [5].

The human herpesviruses (HHVs) are divided to three categories, based on biological characteristics: α-herpesviruses (which include herpes simplex virus (HSV) types 1 (HSV-1) and 2 (HSV-2) , varicella-zoster virus (VZV)), β-herpesviruses (which include cytomegalovirus (CMV), human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), and human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7)), and γ-herpesviruses (which include Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)) [6]. The complication of CMV enteritis in IBD, especially in UC practice, is believed to be caused by CMV reactivation as a result of disruption of intestinal barrier function, inflammation, or strong immunosuppressive therapy, and is known to affect the prognosis of UC [7]. However, the relationship between other HHVs and IBD remains unclear. In our previous study on HHV infection in the colonic mucosa of patients with IBD, we demonstrated that half of the CMV-infected patients had combined infections with EBV or HHV-6, and all the combined infections were cases of UC, indicating a higher rate of subsequent total colorectal resection in patients with mixed infections than in patients with only one type of HHV detected [8]. In the transplantation field, some reports have argued that HHV-6 and CMV infections interact [9,10,11], therefore, understanding the mixed infection status of HHVs may be important for the treatment of IBD. Looking at the relationship with new coronaviruses (SARS-CoV-2) , there are reports suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 may induce reactivation of HSV-1, EBV, and HHV-6/7, and a case of herpes zoster (VZV reactivation) in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [12,13]. If SARS-CoV-2 infection becomes common, vigilance against HHV reactivation may become more crucial. In addition, it is known that the risk of herpes zoster increases during administration of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors [14], which may require further attention and discussion of the need for a herpes zoster vaccine.

2. β-Herpesviruses in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Although the seroprevalence varies depending on the socioeconomic status of countries, 83% (95% uncertainty interval: 78–88) of the general population are seropositive for CMV [42]. The virus remains with the host latently in cells of the early myeloid lineage, including granulocyte–macrophage progenitors and CD14+ monocytes, and endothelial cells [43,44]. The latent CMV can be reactivated under immunocompromised status, such as patients with AIDS, organ transplantation, hematological malignancy, cancer therapy, and corticosteroid therapy [45], driven by inflammation [46]. TNF-α can directly stimulate firing of the CMV immediate–early promoter and CMV reactivation [44,47]. CMV colitis, which occurs most commonly in the gastrointestinal tract, can develop in patients with IBD, especially in UC, and this is associated with a significant clinical morbidity, such as a toxic megacolon, requirement of colectomy, and high mortality rate [48,49]. Regarding risk factors for CMV colitis in UC, these include: higher age, higher activity of mucosal inflammation, and use of immunosuppressive treatment, including corticosteroids and thiopurines, but not TNF-α inhibitors [7].

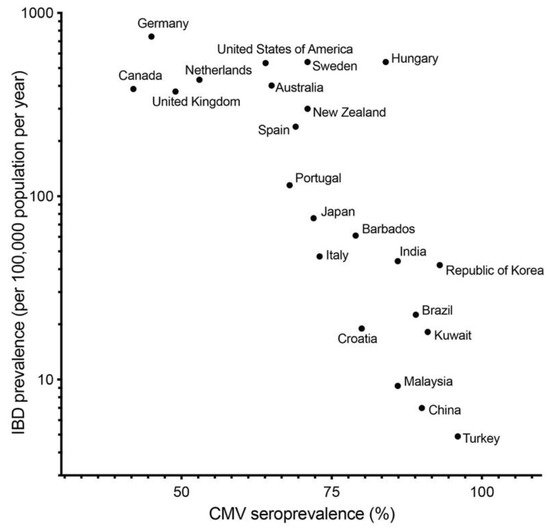

CMV infection can be associated not only with activity of UC and treatment, but also initiation and exacerbation of UC. In fact, several papers showed that colonic mucosa of UC patients have higher prevalence of CMV DNA than that of normal and CD patients [50,51,52]. In our previous study, we described that the prevalence of CMV DNA in colonic mucosa in patients with UC (13.9%) was higher than that in the control group (3.4%) and patients with CD (0%) [8]. As seroprevalence of CMV in developed countries is generally lower than in developing countries, the seroprevalence of CMV [42] and prevalence of IBD [53] are negatively correlated ( Figure 1 ). This correlation indicates that CMV infection per se is not a key etiology of IBD.

CMV infection is clinically diagnosed based on positive serology, histopathological detection of owl’s eye inclusions and/or immunohistochemically stained cells, or PCR for CMV DNA in clinical samples such as blood, stool, or colonic mucosal specimens. PCR for CMV detection is reported to be more sensitive than immunohistochemistry [54,55]. Therefore, quantitative real-time PCR performed for samples of colonic mucosa would be a useful assay for accurate diagnosis of CMV colitis [56]. The therapeutic strategy for CMV infection in flared UC is still controversial. It is not easy to determine whether detected CMV in inflamed colonic mucosa is a pathogen or bystander. In fact, some studies showed the efficacy of antiviral treatment with ganciclovir or foscarnet for CMV infection in active UC patients, but others did not. A meta-analysis of 15 studies showed that antiviral treatment benefited only a subgroup of UC patients who were refractory to corticosteroids, whereas no benefit was observed in the overall UC population [57]. It is proposed that UC patients with high viral load detected by quantitative PCR in colonic mucosa should be a reasonable indication of antiviral treatment from recent studies; the majority of patients with a high viral load had a response to antiviral treatment [58] and high viral load in colonic mucosa predicted the failure of corticosteroids and short-term risk of colectomy [59].

Studies of HHV-6-associated colitis are very limited [65,66], although HHV-6/7 reactivation can cause encephalitis in immunocompromised patients [67]. Our previous study showed that HHV-6 was detected in 9.2% of colonic mucosa samples of IBD patients; however, there was no difference in the prevalence among UC patients, CD patients, and the healthy controls [8]. Moreover, no significant risk factors associated with HHV-6 infection were found in the logistic regression analysis, indicating that HHV-6 infection in the colon is not related to mucosal inflammation in IBD [8].

3. Co-Reactivation of Human Herpesviruses

Some HHVs, such as CMV and EBV, are clinically relevant viruses and can be reactivated in immunodeficient, immunosuppressed, and immunosenescent states [84,85], therefore, co-reactivation of herpesviruses has been reported as clinically important. A recent study showed that older patients under high intensity immunosuppressive treatment and/or chemotherapy had a higher frequency of EBV co-reactivation with CMV viremia [86]. Co-reactivation of HSV and CMV was frequently seen among patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [87]. Regarding patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), co-reactivation of CMV and EBV was associated with poor prognosis after allogeneic stem cell transplantation [88]. In terms of IBD, we previously reported that combined infection of EBV or HHV-6 with CMV could be associated with pathogenesis of UC and poor clinical outcome [8]. We described that 5 of 11 (45%) and 1 of 11 (9%) UC patients with CMV also have co-existing EBV and HHV-6 infection, respectively, and a combined infection by EBV or HHV-6 with CMV is independently and significantly associated with an increased risk of colectomy in patients with UC [8]. In line with our study, Nahar S et al. evaluated the prevalence of HHVs in stool samples, which demonstrated a prevalence of CMV, EBV, and HHV-6 of 36.6%, 36.6%, and 11.3%, respectively, and a higher rate of co-existence of CMV and EBV and/or HHV-6 in patients with active UC (24.1%) [89]. HHV-6 could be a co-factor for the development of CMV infection in patients undergoing transplantation [10,11], and CMV primary infection could induce EBV reactivation [9]. These findings suggest that such interactions between CMV and other HHVs might promote mucosal inflammation in IBD, particularly in UC. Therefore, further basic and clinical research would be needed to clarify the role of co-reactivation of HHVs in IBD.

4. Human Herpesviruses in the Era of COVID-19

COVID-19, which is caused by SARS-CoV-2, can infect multiple organs, not only the lungs, but epithelial cells and the gastrointestinal tract [90]. Most individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 have a mild to moderate disease course, while some of them progress to severe or critical disease, such as ARDS, pulmonary edema, cytokine storm, diffuse coagulopathy, and multiple organ failure [91], and require intensive care with mechanical ventilation/extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory support [92]. Therefore, therapies for moderate to severe COVID-19 require antiviral and immunomodulatory treatment, such as corticosteroids, anti-interleukin 6 receptor antibody, and inhibitors for the JAK pathway and spleen tyrosine kinase [93]. That distinct phenotype could be characterized by host immune responses. Hadjadj J et al. showed that impaired IFN type I activity, which was characterized by no IFN-β and low IFN-α production and activity, was associated with a persistent blood viral load, exacerbated inflammatory responses, and disease severity. These backgrounds can influence other viral infections. Several observational studies showed that patients with herpes zoster and pityriasis rosea, which is associated with reactivation of HHV-6/7, increased in number during the COVID-19 pandemic [12,13]. Critical COVID-19 patients were reported to develop EBV, CMV, and HHV-6 reactivations while in the intensive care unit (ICU) [94]. A suggestive clinical case report showed that a critical COVID-19 patient simultaneously worsened with reactivation of HSV-1 and VZV identified by next-generation sequencing from blood and sputum [95]. Co-reactivation of these herpesviruses, on the other hand, was reported to be associated with a prolonged mechanical ventilation duration, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) duration, ICU stay, and hospital stay [87]. These data collectively indicate that COVID-19 pneumonia could lead to a vicious cycle of co-reactivation of latent viruses and aggravation the COVID-19 disease course, and possibly severity of enterocolitis in IBD patients with COVID-19.

Another influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on other infections is a decline in regular check-ups and routine vaccinations. The childhood vaccination rate among 16-month-olds, which includes VZV, in Texas declined by 58% during the COVID-19 pandemic [96]. A cohort in Michigan also showed a reduction in childhood vaccination, especially in 5–16-month-olds, during the COVID-19 pandemic [97]. Efforts such as educating healthcare workers and parents are necessary to ensure that appropriate vaccinations continue to be provided during a pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, as several studies reported, could cause lifestyle changes and psychological stress [98,99,100,101]. In patients with IBD, lifestyle factors, such as smoking or drug adherence, and psychological stresses were reported to significantly influence the disease activity [102,103,104,105]. The pandemic and lockdown also resulted in reduced access to face-to-face outpatient clinics for IBD patients and diagnostic examinations, such as endoscopy [106,107]. Taken together, the pandemic and lockdown would change patients’ symptoms and the clinical course of IBD.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9091870