Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Business

Knowledge management (KM), a process of acquiring, converting, applying, and protecting knowledge assets, is crucial for value creation

- knowledge management (KM)

- knowledge acquisition

- knowledge conversion

- knowledge application

- knowledge protection

- entrepreneurial orientation (EO)

1. Introduction

In light of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, many businesses have been forced to close temporarily and shift to a remote work paradigm. As a result, cloud computing and online communications systems, such as Zoom, Microsoft Team, Google Meet, and Cisco Webex, are in higher demand around the world. These digital productivity tools have increased the volume of data generated from various sources, including business processes, social media platforms, sensor data, and machine-to-machine data. To remain competitive, a system that can capture, share, apply, and store these essential data is required. Hence, knowledge management (KM) appears to be more important than ever for organizational success.

KM is a discipline that involves the process of acquiring, converting, applying, and protecting a firm’s information and knowledge assets [1]. By making data and information visible and accessible to organization members when needed, effective KM can help build new competitive advantages. While an increasing number of studies examine KM in relation to desired organizational outcomes, little is known about how different KM dimensions affect organizational outcomes. Instead, previous research has tended to consider KM as a composite construct by combining all of its dimensions into a single variable, thereby making it difficult to assess the impact of each dimension of KM on the organizational outcomes [2][3][4]. In this regard, Mills and Smith [5] contend that not all KM dimensions are directly related to organizational performance and warrant further study concerning this matter. Consistent with this perspective, Mohamad et al. [6] assessed the impacts of multiple dimensions of KM on firm innovativeness, and they found that knowledge conversion was not positively related to innovativeness. As a result, a more comprehensive understanding of how each dimension of KM is linked to organizational outcomes is required.

Small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for the majority of businesses globally, and they play an important role in GDP growth, job creation, and entrepreneurship. Despite their importance, existing literature shows that most KM research has been conducted in large organizations, while KM in SMEs is still at infancy stage and provides only fragmentary insight [7][8][9]. It is crucial to notice that SMEs are not a scaled-down replica of large organizations, and they are substantially different in many ways. SMEs, in comparison to large corporations, are typically less flexible in terms of human and financial resources. At the same time, SMEs have advantages over large organizations in that they are less bureaucratic, quick to change, and more flexible [10][11]. Hence, KM theories and practices that work well for large organizations may not be a good fit for SMEs [12][13]. Moreover, the limited resources of many SMEs prevent them from pursuing too many strategic options which would spread their resources too thinly. As a result, identifying which dimensions of KM can best boost organizational performance goals is critical in the short term and can be extended to improve on long term production and performance.

Extant literature has studied the performance contribution of KM; however, the results are mixed. Few scholars have reported significant and positive relationships between KM dimensions and desired organizational outcomes [14][15], while others have found an insignificant or indirect relationship between some KM dimensions and desired organizational outcomes [6][9][10]. These mixed results left the KM-performance debate open, and scholars have stressed the necessity for more research on the moderators to scrutinize the inconclusive results. The characteristics of entrepreneurial orientation (EO), such as innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking, may facilitate KM development and lead to better utilization of knowledge resources [16][17]. When KM processes and EO work together, it is assumed that they will improve organizational strategy and assure organizational success [18][19][20].

To summarize, the relationship between particular KM dimensions and firm performance is still a point of contention in the literature, and researchers have emphasized the importance of more study on moderators to scrutinize the inconsistent results. Additionally, there is still a lack of consensus regarding the performance contribution of KM in the context of SMEs. Given the enormous number of SMEs and their significant contribution to economic development, this study aims to extend and integrate these streams of research and fill the aforementioned gaps by presenting a model that combines KM processes, EO, and the performance of SMEs.

2. Knowledge Management Process, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and Performance in SMEs

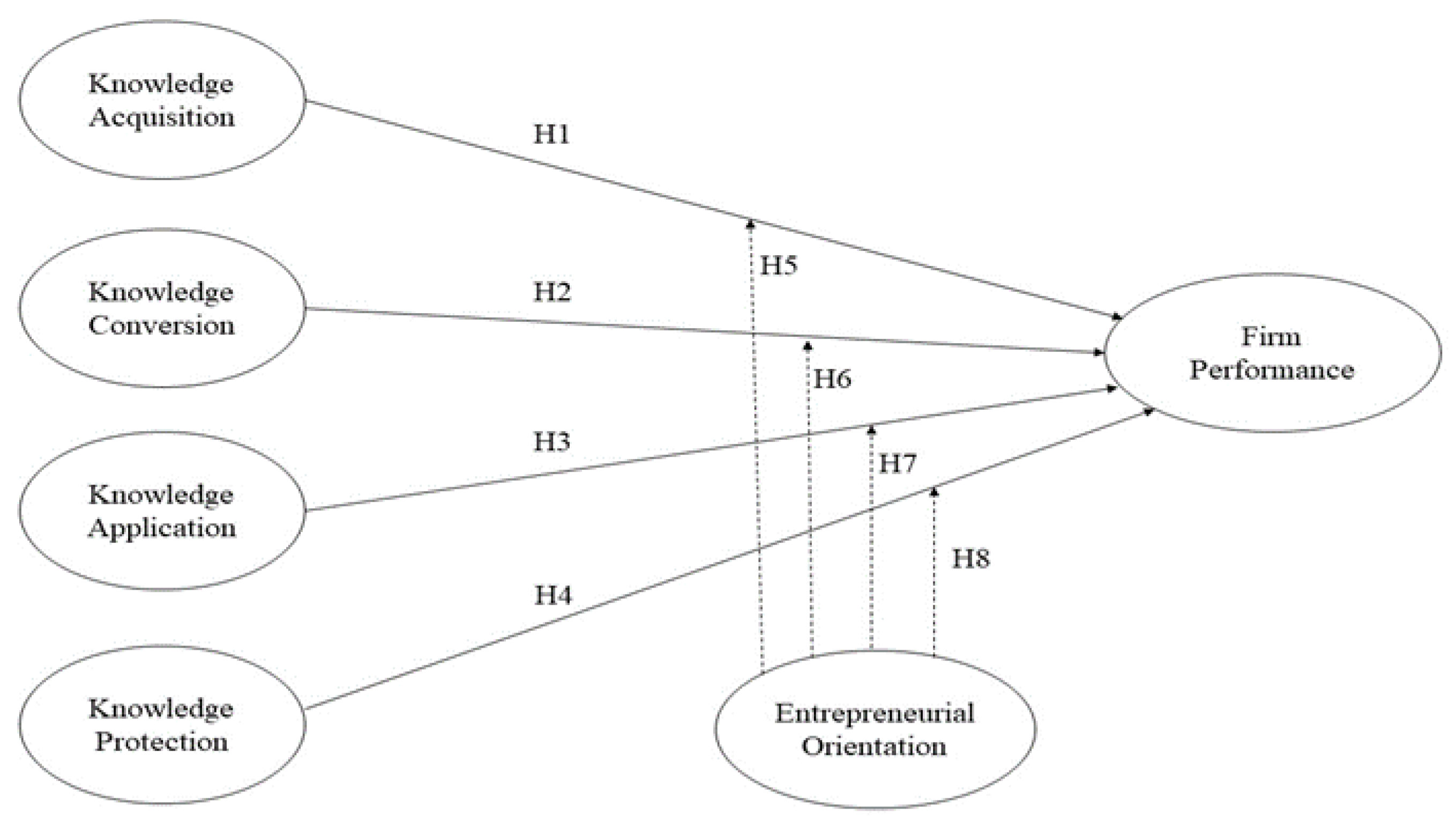

Knowledge is the most crucial resource for firms to establish a long-term competitive advantage and differentiate themselves from their competitors, according to Knowledge-based view (KBV) [21][22][23]. Given the importance of knowledge, firms must implement KM to successfully manage their knowledge. For this study, we follow Gold et al. [1], who proposed four dimensions of KM process capabilities as significant determinants of firm performance: knowledge acquisition, knowledge conversion, knowledge application, and knowledge preservation. Having knowledge assets, however, does not guarantee a competitive advantage in today’s volatile business environment [2][24]. According to dynamic capability view (DCV), firms must integrate and build competencies to maximize the potential of their resources [25]. In this study, EO is identified as a firm’s dynamic capability [19]. If KM and EO are aligned, it is expected that they will attain complementarities that will lead to superior firm performance. Figure 1 depicts the relationships between KM process capabilities, EO, and firm performance.

Figure 1. Relationships between KM process capabilities, EO, and firm performance,.

2.1. Knowledge Acquisition and Firm Performance

If a firm wants to increase its understanding of consumer needs, the business environment, or rival actions, it must engage in knowledge acquisition, which is the process of gathering information from a variety of sources [1]. Firms must establish relationships with business partners, such as clients, suppliers, and group firms, in order to have access to the knowledge and information needed to produce productive and innovative operations [26][27]. By establishing a solid knowledge base, firms can improve their ability to respond effectively to changing market situations [8][28]. A solid knowledge base can aid businesses in making better decisions, lowering employee turnover, and maximizing market opportunities. Several lines of evidence suggest that a firm’s competitive advantage and performance are heavily reliant on knowledge acquisition that improves the availability of the relevant knowledge to make the best judgments [29][30][31]. As a result, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a positive relationship between knowledge acquisition and firm performance.

2.2. Knowledge Conversion and Firm Performance

Knowledge conversion assists firms in making the greatest use of their knowledge by transforming individual knowledge into organizational knowledge [1]. The conversion of knowledge not only entails the act of converting tacit to explicit and explicit to tacit knowledge, but it also facilitates knowledge exchange [23]. This process is vital for the firms to avoid losing critical information or skills due to the departure of one or more employees. Therefore, firms must make reasonable efforts to build a culture that encourages employees to create, store, and share their knowledge. Knowledge conversion has been defined in previous studies as a crucial variable that can contribute to creativity, innovation and ultimately, competitive advantage [32][33][34]. Knowledge conversion has also been shown to improve firm performance by creating important organizational knowledge and making it timely available in a shared database [15]. Hence, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a positive relationship between knowledge conversion and firm performance.

2.3. Knowledge Application and Firm Performance

The next stage is to put the structured knowledge into practice. Knowledge application allows a firm to react more quickly to changing business conditions by incorporating knowledge into new products or processes [1][15]. Knowledge application, according to Alavi and Leidner [35], is the most significant KM process for improving organizational performance. Zaim et al. [36] backs up this claim, finding that knowledge application had the most substantial impact on improving KM-related organizational performance. On the other hand, knowledge application has been found to play a critical role in enhancing operational procedures and fostering better decisions, all of which contribute to improved business performance [30][31]. It is also a key determinant when it comes to innovation [33][37]. As claimed by Serrasqueiro et al. [38], R&D activities can make a considerable contribution to the growth of SMEs. Hence, the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is a positive relationship between knowledge application and firm performance.

2.4. Knowledge Protection and Firm Performance

Knowledge protection refers to a firm’s ability to secure its intellectual knowledge from illegal theft and inappropriate use [1]. If a firm implements intellectual property protections, such as a patent, copyright, or trademark, knowledge protection will be more effective. These safeguards give the company the right to prevent competitors from copying its ideas or inventions, as well as the ability to benefit from licensing its intellectual property rights [37]. Knowledge protection is positively related to organizational performance in several studies. Ferri et al. [39], for example, offered empirical evidence that the patenting procedure has a positive impact on spin-off performance. Similarly, Liu and Deng [15] discovered that knowledge protection improves business process outsourcing performance since other companies are unable to quickly copy the ideas or inventions. Based on the preceding arguments, the following hypothesis is formulated:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There is a positive relationship between knowledge protection and firm performance.

2.5. The Moderating Effects of EO

Since its inception in 1970, EO has become one of the most widely studied entrepreneurship and management concepts. EO refers to the decision-making styles, management practices, and behaviors characterized by innovative, proactiveness, and risk-taking [40][41][42]. Creating an EO culture will assist firms in identifying and exploiting new possibilities, creating new values, and becoming market leaders. Not only that, but EO is seen as a critical driver of a company’s competitiveness and performance, especially in dynamic business environments [43][44][45].

Furthermore, EO has been found to interact with other organizational factors, such as manufacturing capabilities, to improve organizational performance [46]. A firm may seek to develop flexibility and cost leadership strategies, such as investment in technology and automated processes, to strengthen its competitive position by having greater EO. The moderating effect of EO was also discovered by Yousaf and Majid [47], who discovered that EO strengthens the relationship between organizational flexibility and strategic business performance. The rapid development of new products and services, propensity to intensely challenge competitors, and greater risk-taking behaviors resulting from a greater degree of EO can boost firms’ flexibility and improve the strategic business performance.

On the other hand, EO directs firms towards resource leveraging to unlock new market opportunities [19][48]. Wiklund and Shepherd [17] discovered that EO moderates the positive relationship between knowledge-based resources and SMEs’ performance. The authors argue that, when EO is low, firms may be reluctant to maximize the utilization of knowledge-based resources by perceiving such resources as less important. Under the EO culture, firms are motivated to configure knowledge-based resources into commercially valuable resource bundles. These valuable resource bundlers can help the firms achieve a higher absorptive capacity level that results in superior performance [49].

EO is also expected to strengthen KM [50][51]. Knowledge acquisition, conversion, application, and protection are all critical KM processes for improving business performance. However, equally important are the positive mindset attributes to apply such processes to reach the organizational goals. It is known that EO requires firms to be more innovative, risk-taking, and proactive in their operations to identify and exploit new market opportunities. These positive mindset attributes may motivate the firms to develop greater KM processes in order to create more innovative products or services that the competitors will not be able to match or exceed. When EO is low, on the other hand, a firm may be hesitant to develop KM processes at a higher level which are often risky and costly. In light of the foregoing discussion, the following hypotheses regard the moderating effect of the EO in the KM-firm performance relationship are postulated:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

EO positively moderates the relationship between knowledge acquisition and firm performance.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

EO positively moderates the relationship between knowledge conversion and firm performance.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

EO positively moderates the relationship between knowledge application and firm performance.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

EO positively moderates the relationship between knowledge protection and firm performance.

3. Conclusions

We address Mills and Smith [5]’s call for KM to be considered as a multidimensional construct to effectively evaluate KM’s consequences. In addition, we view EO as an important complementary asset that can strengthen the relationship between KM processes and firm performance by positively leveraging its moderating effect.

Consistent with prior studies, the results indicate that knowledge acquisition has a positive and significant relationship with firm performance [30][31]. To withstand today’s dynamic business environment, firms must place great emphasis on knowledge acquisition. This process enables firms to continuously expand and update their existing knowledge base by identifying and acquiring valuable know-how; thus, firms can improve their responsiveness to market change and performance. Therefore, firms should establish relationships with business partners, such as clients, suppliers, and group firms, in order to have access to the knowledge and information needed to generate new knowledge and develop innovative advances [26][27].

Furthermore, the results revealed that knowledge conversion is significantly and positively related to firm performance, and this relationship is the strongest in the model. This finding corroborates previous studies that view knowledge conversion as a core capability to enhance firm performance [15][32]. Firms need to develop a framework for organizing, integrating, or disseminating knowledge as these processes enable firms to reduce redundancy and replace obsolete knowledge, which represents a key to achieving superior performance.

As predicted, knowledge protection is found to be positively and significantly related to firm performance. This finding is consistent with prior research stressing the benefits of building mechanisms for securing knowledge assets of the firms [39]. It appears that firms with strong knowledge protection capability can protect their proprietary knowledge from being illegally or inappropriately used by others (inside and outside firms). Thus, these firms can sustain their performance for a longer period.

One interesting finding is that, among the four process capabilities of KM, only knowledge application was not significantly related to firm performance. This finding is supported by some previous studies, which found that not all KM capabilities are directly related to firm performance [5][6]. The insignificant effect of knowledge application on performance might be explained by less financial and administrative resources in SMEs [52]. Most SMEs tend to employ one or two employees to hold the firms’ key knowledge due to resource constraints. Consequently, it may impede the flow of knowledge and hamper innovative actions, resulting in the loss of a valuable commercial opportunity.

Furthermore, EO has demonstrated its ability to act as a moderator in the relationship between KM processes and SMEs performance. Through EO, the relationship between knowledge application and performance becomes stronger. This finding backs up Wiklund and Shepherd [17]’s findings that EO can improve firm performance by maximizing the utilization of knowledge-based resources. It appears that EO, which is defined by risk-taking, inventiveness, and proactiveness, may inspire businesses to share and utilize knowledge in order to exploit new opportunities [49][51]. Taking EO as an organizational climate, this finding backs up Li et al. [50]’s claim that EO can aid the firms in achieving superior performance by enhancing knowledge application quality.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13179791

References

- Gold, A.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A. Knowledge management: An organisational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214.

- Bamel, U.K.; Bamel, N. Organisational resources, KM process capability and strategic flexibility: A dynamic resource-capability perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1555–1572.

- Koohang, A.; Paliszkiewicz, J.; Goluchowski, J. The impact of leadership on trust, knowledge management, and organisational performance: A research model. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 521–537.

- Lai, Y.H. The moderating effect of organisational structure in knowledge management for international ports in Taiwan. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2013, 2, 240–246.

- Mills, A.M.; Smith, T.A. Knowledge management and organisational performance: A decomposed view. J. Knowl. Manag. 2011, 15, 156–171.

- Mohamad, A.A.; Ramayah, T.; Lo, M.C. Sustainable knowledge management and firm innovativeness: The contingent role of innovative culture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6910.

- Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E.; Spadaro, M.R. The spread of knowledge management in SMEs: A scenario in evolution. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10210–10232.

- Martinez-Conesa, I.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Carayannis, E.G. On the path towards open innovation: Assessing the role of knowledge management capability and environmental dynamism in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 553–570.

- Ngah, R.; Wong, K.Y. Linking knowledge management to competitive strategies of knowledge-based SMEs. Bottom Line 2020, 33, 42–59.

- Kmieciak, R.; Michna, A. Knowledge management orientation, innovativeness, and competitive intensity: Evidence from Polish SMEs. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2018, 16, 559–572.

- Nunes, P.M.; Serrasqueiro, Z.; Leitão, J. Is there a linear relationship between R&D intensity and growth? Empirical evidence of non-high-tech vs. high-tech SMEs. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 36–53.

- Durst, S.; Runar Edvardsson, I. Knowledge management in SMEs: A literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2012, 16, 879–903.

- Massaro, M.; Handley, K.; Bagnoli, C.; Dumay, J. Knowledge management in small and medium enterprises: A structured literature review. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 258–291.

- Balasubramanian, S.; Al-Ahbabi, S.; Sreejith, S. Knowledge management processes and performance. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 1–21.

- Liu, S.; Deng, Z. Understanding knowledge management capability in business process outsourcing: A cluster analysis. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 124–138.

- Alshanty, A.M.; Emeagwali, O.L. Market-sensing capability, knowledge creation and innovation: The moderating role of entrepreneurial-orientation. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 171–178.

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314.

- Bhuian, S.N.; Menguc, B.; Bell, S.J. Just entrepreneurial enough: The moderating effect of entrepreneurship on the relationship between market orientation and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 9–17.

- Liu, H.; Ding, X.H.; Guo, H.; Luo, J.H. How does slack affect product innovation in high-tech Chinese firms: The contingent value of entrepreneurial orientation. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2014, 31, 47–68.

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 135–172.

- Grant, R. The knowledge-based view of the firm: Implications for management practice. Long Range Plan. 1997, 30, 450–454.

- Irwin, K.C.; Landay, K.M.; Aaron, J.R.; McDowell, W.C.; Marino, L.D.; Geho, P.R. Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and human resources outsourcing (HRO): A “HERO” combination for SME performance. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 90, 134–140.

- Nonaka, I. A dynamic theory of organisational knowledge creation. Organ. Sci. 1994, 5, 14–37.

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120.

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533.

- Silva, M.J.; Leitão, J. Cooperation in innovation practices among firms in Portugal: Do external partners stimulate innovative advances? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2009, 7, 391–403.

- Pereira, D.; Leitão, J. Absorptive capacity, coopetition and generation of product innovation: Contrasting Italian and Portuguese manufacturing firms. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2016, 71, 10–37.

- Obeidat, B.Y.; Tarhini, A.; Masa’deh, R.E.; Aqqad, N.O. The impact of intellectual capital on innovation via the mediating role of knowledge management: A structural equation modelling approach. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 273–298.

- Al-Sulami, Z.A.; Rashid, A.M.; Ali, N. The role of information technology to support knowledge management processes in higher education of Malaysian private universities. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2014, 4, 423–434.

- Loke, W.; Fakhrorazi, A.; Doktoralina, C.; Lim, F. The zeitgeist of knowledge management in this millennium: Does KM elements still matter in nowadays firm performance? Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3127–3134.

- Xie, X.; Zou, H.; Qi, G. Knowledge absorptive capacity and innovation performance in high-tech companies: A multi-mediating analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 289–297.

- Eren, A.S.; Ciceklioglu, H. The impact of knowledge management capabilities on innovation: Evidence from a Turkish banking call center sector. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 60, 184–209.

- Mohamad, A.A.; Ramayah, T.; Lo, M.C. Knowledge management in MSC Malaysia: The role of information technology capability. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18, 651–660.

- Tseng, S.M. The correlation between organisational culture and knowledge conversion on corporate performance. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 269–284.

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136.

- Zaim, H.; Muhammed, S.; Tarim, M. Relationship between knowledge management processes and performance: Critical role of knowledge utilisation in organisations. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 17, 24–38.

- Pinzon-Castro, S.Y.; Maldonado-Guzman, G.; Marin-Aguilar, J.T. Market knowledge management and performance in Mexican small business. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 127–137.

- Serrasqueiro, Z.; Nunes, P.M.; Leitão, J.; Armada, M. Are there non-linearities between SME growth and its determinants? A quantile approach. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2010, 19, 1071–1108.

- Ferri, S.; Fiorentino, R.; Parmentola, A.; Sapio, A. Patenting or not? The dilemma of academic spin-off founders. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2019, 25, 84–103.

- Covin, J.G.; Slevin, D.P. Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 75–87.

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 3–18.

- Wales, W.J.; Covin, J.G.; Monsen, E. Entrepreneurial orientation: The necessity of a multilevel conceptualization. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2020, 14, 639–660.

- Ali, G.A.; Hilman, H.; Gorondutse, A.H. Effect of entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation and total quality management on performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 1503–1531.

- Bauweraerts, J.; Pongelli, C.; Sciascia, S.; Mazzola, P.; Minichilli, A. Transforming entrepreneurial orientation into performance in family SMEs: Are non-family CEOs better than family CEOs? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2021, 1–32.

- Ibidunni, A.S.; Ibidunni, O.M.; Olokundun, A.M.; Oke, O.A.; Ayeni, A.W.; Falola, H.O.; Salau, O.P.; Borishade, T.T. Examining the moderating effect of entrepreneurs’ demographic characteristics on strategic entrepreneurial orientations and competitiveness of SMEs. J. Entrep. Educ. 2018, 21, 1–8.

- Chavez, R.; Yu, W.; Jacobs, M.A.; Feng, M. Manufacturing capability and organizational performance: The role of entrepreneurial orientation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 184, 33–46.

- Yousaf, Z.; Majid, A. Organizational network and strategic business performance: Does organizational flexibility and entrepreneurial orientation really matter? J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 268–285.

- Griffith, D.A.; Noble, S.M.; Chen, Q. The performance implications of entrepreneurial proclivity: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Retailing 2006, 82, 51–62.

- Wales, W.J.; Gupta, V.K.; Mousa, F.T. Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 357–383.

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, M.; Guo, H. How entrepreneurial orientation moderates the effects of knowledge management on innovation. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. Off. J. Int. Fed. Syst. Res. 2009, 26, 645–660.

- Luu, T.T. Psychological contract and knowledge sharing: CSR as an antecedent and entrepreneurial orientation as a moderator. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2016, 21, 2–19.

- Silva, M.J.; Leitao, J.; Raposo, M. Barriers to innovation faced by manufacturing firms in Portugal: How to overcome it for fostering business excellence? Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2008, 1, 92–105.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!