Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Polymer Science

The utilization of lignocellulosic biomass in various applications has a promising potential as advanced technology progresses due to its renowned advantages as cheap and abundant feedstock. The main drawback in the utilization of this type of biomass is the essential requirement for the pretreatment process. The most common pretreatment process applied is chemical pretreatment. However, it is a non-eco-friendly process.

- non-chemical pretreatment

- lignocellulosic biomass

- bioproducts

1. Introduction

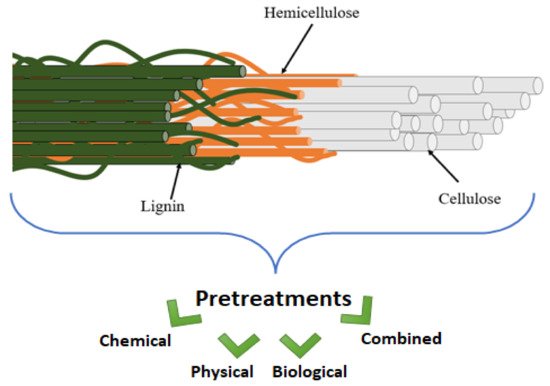

Many industries currently produce many tons of agro-industrial wastes. However, direct utilization of lignocellulosic biomass as a feedstock for bioproducts is challenging due to their complex structure (as represented in Figure 1). A variety of useful components, including sugars, protein, lipids, cellulose, and lignin, are present in natural fibres. The major issue that limits their utilization is, however, the tight bonding within their components [1]. Cross-linking of polysaccharides and lignin occurs through ester and ether bonds, while microfibrils produced by cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin aid in the stability of plant cell wall structure [2][3]. These strong cross-linking connections exist between the components of the plant cell wall that act as a barrier to its disintegration.

Figure 1. Overview of the complex structure of natural fibers and pretreatments.

Pretreatment helps to fractionate biomass prior to further processes, making it simpler to handle in the process [4][5][6]. It enables biomass hydrolysis and makes building blocks for biobased products, fuels, and chemicals. It is often the initial stage of the biorefining process and enables the following steps such as enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation to be carried out more quickly, effectively, and economically [7]. The pretreatment method used is entirely dependent on the targeted application. Numerous pretreatment methods are mainly developed to effectively separate these interconnected components in order to get the most advantages from the lignocellulosic biomass’s constituents.

Pretreatment of natural fibres is not as straightforward as it may seem. In fact, it is the second most expensive procedure after the installation of a power generator. Hydrogen bond disruption, cross-linked matrix disruption, as well as increased porosity and surface area, are the three objectives that a good pretreatment technique accomplishes in crystalline cellulose. Additionally, the result of pretreatment varies attributed to the different ratios of cell wall components [8]. More criteria to take into consideration for efficient and economically feasible pretreatment process include less chemical usage, prevention of hemicellulose and cellulose from denaturation, minimum energy demand, low price, and the capacity to reduce size.

Biomass recalcitrance is a term used for the ability of natural fibres to resist chemical and biological degradation. While there are many components involved in the recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass, the crystalline structure of cellulose, the degree of lignification, accessible surface area (porosity), the structural heterogeneity, and complexity of cell-wall are primary causes [9][10]. As a consequence of breaking the resistant structure of lignocellulose, it causes lignin sheath, hemicellulose, and crystallinity to all be degraded, as well as casuing a decrease in cellulose’s degree of polymerization [11].

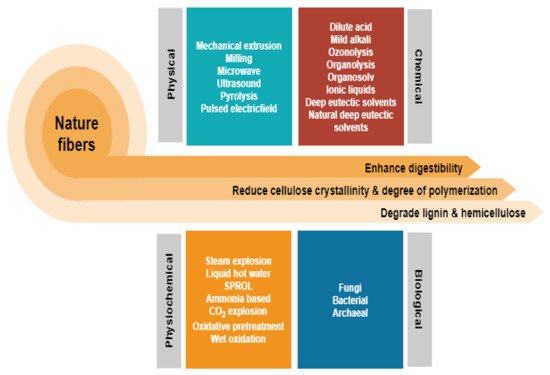

Depending on the types of natural fibres employed, the preference for the pretreatment method varies according to the composition of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. Figure 2 depicts the general differences between the many common approaches which come under the four categories of physical, chemical, biological, and combination pretreatment [4]. While some of these methods have successfully transitioned from a research platform to an industrial stage, there are many hurdles, and one of the greatest is the requirement for highly toxic waste generation and high-energy inputs. From here, a serious issue that must be addressed is the lack of green and cost-effective solutions. Nevertheless, it has only lately garnered significant attention as a potential solution to the problem by focusing on the employment of non-chemical pretreatment. This could be reflected by the increment in article publications that reviewed lignocellulosic fibre pretreatment via individual greener approach as highlighted in Table 1 indicating that this topic is increasingly well-known owing to environmental concerns. The development of technology that maximises the use of raw resources, reduces waste, and avoids the use of poisonous and hazardous compounds is critical to accomplishing this objective. However, a review of all greener pretreatment approaches for lignocellulosic biomass is missing in the current literature.

Figure 2. Different pretreatments, which fall into four main categories: physical, chemical, biological, and combination have been used to improve lignocellulosic fractionation for natural fibres.

Table 1. Recent review articles related to greener pretreatment approaches for lignocellulosic biomass.

| No. | Title | Highlights of Review | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Enzymatic pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for enhanced biomethane production-A review |

|

[12] |

| 2. | A review on the environment-friendly emerging techniques for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: Mechanistic insight and advancement |

|

[13] |

| 3. | Recent Insights into Lignocellulosic Biomass Pyrolysis: A Critical Review on Pretreatment, Characterization, and Products Upgrading |

|

[14] |

| 4. | Recent advances in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and value-added products |

|

[15] |

| 5. | Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass |

|

[16] |

Hence, the green pretreatment approaches for lignocellulosic biomass such as physical, biological, and combination methods, as well as their impact on the separation of the complex components of different lignocellulosic sources, are reviewed in more detail in the next sections.

2. Physical Pretreatment

The physical pretreatment allows increasing the specific surface area of the fibres via mechanical comminution. It also contributes to reduce the crystallinity of the natural fibres and enhance their digestibility. The physical pretreatment usually does not affect the chemical composition of natural fibres. Physical pretreatment can be conducted by using milling, extrusion and ultrasound. Physical pretreatment is often an essential step prior to or following chemical or biochemical processing. However, the information on the mechanism of how physical pretreatment modifies the structures of the fibre is still limited.

There are some drawbacks of physical pretreatment that need to be considered. Physical pretreatment lacks the ability to remove the lignin and hemicellulose which limits the enzymes’ access to cellulose. Besides that, physical pretreatment requires high energy consumption which limits its large-scale implementation and environmental safety concerns.

2.1. Mechanical Extrusion

Mechanical extrusion is one of the most conventional methods of pretreatment [17]. In this pretreatment, the fibres are subjected to a heating process (>300 °C) under shear mixing. Due to the combined effects of high temperatures that are maintained in the barrel and the shearing force generated by the rotating screw blades, the amorphous and crystalline cellulose matrix in the biomass residues is disrupted. Besides that, extrusion requires a significant amount of high energy, making it a cost-intensive method and difficult to scale up for industrial purposes [17].

Temperature and screw speed of extrusion are the main important factors. Karunanithy and Muthukumarappan [18] studied the effect of these factors on the pretreatment of corn cobs. When pretreatment was carried out at different temperatures (25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 °C) and different screw speeds (25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 rpm), maximum concentration sugars were obtained at 75 rpm and 125 °C using cellulase and β-glucosidase in the ratio of 1:4, which were nearly 2.0 times higher than the controls.

2.2. Milling

Mechanical milling is used to reduce the crystallinity of cellulose. It can reduce the size of fibre up to 0.2 mm. However, studies found that further reduction of biomass particles below 0.4 mm has no significant effect on the rate and yield of hydrolysis [17]. The type of milling and milling duration are important factors that influence the milling process. These factors can greatly affect the specific surface area, the final degree of polymerization, and a net reduction in cellulose crystallinity.

Wet disk milling has been a popular mechanical pretreatment due to its low energy consumption as compared to other milling processes. Disk milling enhances cellulose hydrolysis by producing fibres and more effective as compared to hammer milling which produces finer bundles [19]. Hideno et al. [20] compared the effect of wet disk milling and conventional ball milling pretreatment method over rice straw. The optimal conditions obtained were 60 min of milling time in case of dry ball milling while 10 repeated milling operations were required in case of wet disk milling.

2.3. Ultrasound

Ultrasound is relatively a new technique used for the pretreatment of fibres [17]. Ultrasound waves affect the physical, chemical, and morphological properties of fibres. Ultrasound treatment leads to the formation of small cavitation bubbles. These bubbles can rupture the cellulose and hemicellulose fractions. The ultrasonic field is influenced by ultrasonic frequency and duration, reactor geometry, and types of solvent used. Besides that, fibres characteristics and reactor configuration also influence the pretreatment [21].

The power and duration of ultrasound are important to be optimised depending on the fibres and slurry characteristics. This is important to meet the pretreatment objectives. Duration of ultrasound pretreatment has maximum effect on pretreatment of fibres. Besides that, a higher ultrasound power level has an adverse effect on the pretreatment. It can lead to the formation of bubbles near the tip of the ultrasound transducer which hinders the transfer of energy to the liquid medium [22].

3. Biological Pretreatment

Retting is a biological process in which enzymatic activity removes non-cellulosic components connected to the fibre bundle, resulting in detached cellulosic fibres. The dew retting uses anaerobic bacteria fermentation and fungal colonization to produce enzymes that hydrolyse fibre-binding components on fibre bundles. Clostridium sp. is an anaerobic bacterium commonly found in lakes, rivers, and ponds. Plant stems were cut and equally scattered in the fields during the dew retting process, where bacteria, sunlight, atmospheric air and dew caused the disintegration of stem cellular tissues and sticky compounds that encircled the fibres [23]. For the dew retting procedure to enhance fungal colonization, locations with a warm day and heavy might dew are recommended.

Bleuze et al. [24] investigated the flax fibre’s modifications during the dew retting process. Microbial colonization can be affected the chemical compositions of cell walls. After seven days, fungal hyphae and parenchyma were found on the epidermis and around fibre bundles, respectively. After the retting process (42 days), signs of parenchyma deterioration and fibre bundle decohesion revealed microbial infestation at the stem’s inner core.

Fila et al. [25] found 23 different varieties of dew-retting agent fungi in Southern Europe. All Aspergillus and Penicillium strains yield high-quality retted flax fibres, according to the researchers. Besides that, under field conditions, Repeckien and Jankauskiene [26] investigated the effects of fungal complexes on flax dew-retting acceleration. Cladosporium species variations with high colonization rates (25–29%) have been identified as a good fungus for fibre separation. Most fungi survived on flax fed with fungal complex N-3, which contained six different fungal strains.

On a commercial scale, Jankauskiene et al. [27] optimised the dew retting method. Two fungal combinations were created and put to straw after the swath was pulled and returned. Furthermore, after spraying Cladosporium herbarum suspension during fibre harvesting, extremely high fibre separation was found.

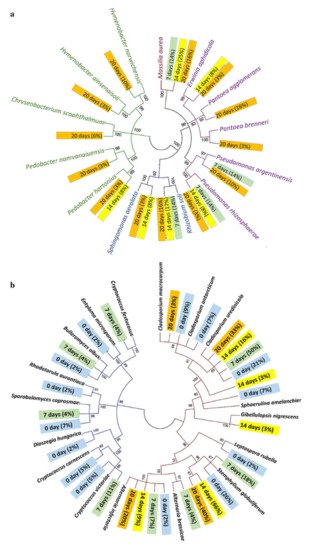

Bacterial and Fungi Interaction

Fungi colonization is thought to be the most important enzymatic active mechanism for dew retting. Recent research has focused on the interplay of the bacterial and fungal communities during dew retting. The association between the chemical contents of hemp fibres and microbial population fluctuation during the retting process was investigated by Liu et al. [28]. In the first seven days, fungal colonization was discovered with very little bacteria. After 20 days, there was a gradually risen in bacterial attachments on the fibre surface, with fewer fungal hyphae. The area with the highest bacterial concentration was found to severely deteriorate. The phylogenetic tree for the bacterial and fungal population in dew-retting hemp fibres is shown in Figure 3. While Table 2 shows ultrastructural changes in hemp stems and fibres as a result of microbial activity during the retting process.

Figure 3. The phylogenetic tree of the (a) bacterial and (b) fungus communities found in hemp fibre samples. The color of the branches indicates the type of proteobacteria present, while the color of the tag indicates the number of bacteria/fungi present on different days [28].

Table 2. Highlights of ultrastructural changes on hemp stems and fibres associated with microbial activity during the retting process [29].

| Retting Period | 0 Days | 7 Days | 14–20 Days | After 50 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes in the hemp stem’s and fibre’s ultrastructure | (i) Stem with a well-preserved layered structure (ii) Un-collapsed, unbroken cells with their original cell geometry (iii) Living cells with cytoplasm (iv) Cuticle and trichomes are unharmed on the clear surface. (v) Chloroplasts in abundance in the upper epidermis |

(i) The structure as a whole is in good condition. (ii) Fungal growth on the outside of the stems and inside the stems (iii) With damaged epidermis and parenchyma, cellular architecture is less stable. |

(i) Cuticle has seriously deteriorated. (ii) Changes in cellular anatomy, as well as significant loss of live cells (iii) Fibre bundles were isolated from each other and the epidermis. (iv) Thick-walled cells populate seldom; parenchyma degrades completely, although chlorenchyma suffers less harm. (v) Bast fibres with sporadic moderate attacks (vi) Fungi colonisation and decay morphology were both affected by fibre morphology. |

(i) The structure of hemp was severely harmed and dissolved. (ii) The epidermis and cambium were heavily invaded by dominating bacteria. (iii) In the bast regions, the parenchyma cells have been destroyed, and the structural integrity has been lost. (iv) All cell types, including fibre cells, have hyphae inside their lumina. (v) BFIs are more intense inside the stem. (vi) Anatomy and ultrastructure have been severely harmed. (vii) Bast fibres with a thick wall and degradation properties (viii) Effects on the ultrastructure of the fibre wall.

|

| The dynamics and activity of microbes | Fungi (i) Rarely seen Bacteria (ii) Not observed Fungi |

Fungi (i) Mycelia with sparse growth (ii) Less variety (iii) Outside of the cortical layers, colonisation occurs largely in live cells. (iv) Trichomes near to the surface trichomes have dense colonisation. (v) Dependence on readily available food (vi) Damage to cell walls is reduced. Bacteria (i) Less abundant |

Fungi (i) Extensive and plentiful (ii) Mycelia densely covering the cuticle (iii) diverse population (iv) a large number of spores (v) Interactions and activities that are intense Bacteria (i) Abundant (ii) Diverse population iii) Over the cuticle, colonies (iv) Associated with hyphae and fungal spores (v) After 20 days, there are more noticeable activity (vi) Cuticle has severely deteriorated |

Fungi (i) Less abundant on the outside of the stem (ii) Mycelia on the surface is dead, but there are active hyphae inside the stem (iii) Mycelia, an invading bacteria’s sole source of nourishment, showed bacterial mycophagy (i.e., extracellular and endocellular biotrophic and extracellular necrotrophic activities). Bacteria (i) Highly abundant inside and outside the stems (ii) Highly dominant and diverse role. (iii) Visible as dense overlay representing (a) Biofilms (b) Morphologically different colonies (c) Randomly scattered cells (iv) Showed strong BFIs (v) Using fungal highways, bacterial movement occurs over and inside the hemp stem. (vi) Cutinolytic and cellulolytic activities were improved. |

4. Combination Pretreatment

It can be noticed from the green pretreatment techniques applied to pretreat the lignocellulosic biomass reviewed in the previous section that, while each pretreatment method makes a significant contribution, no single pretreatment approach yields efficient results without its own inherent limitations. Therefore, the combined pretreatment strategies could minimise the drawbacks while still achieving the intended result.

4.1. Physiochemical Pretreatment

Physiochemical pretreatment could be achieved by temperature elevation and irradiation in the processing of lignocellulosic material. Physiochemical pretreatment by steam such as superheated steam, hydrothermal and steam explosion is the most common pretreatments applied on natural fibre for several purposes. Physiochemical pretreatment is usually applied to remove the hemicellulose and lignin from the natural fibres [30].

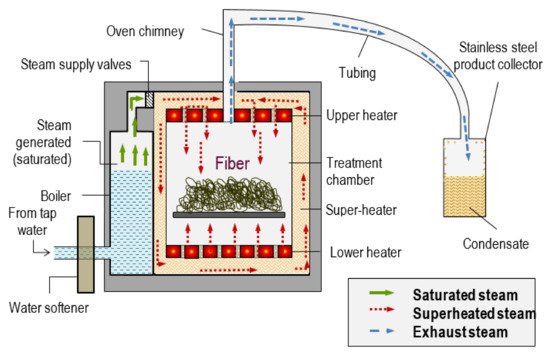

4.1.1. Superheated Steam

Pretreatment of fibres by superheated steam is gaining interest recently, as this pretreatment is considered as an environmentally friendly technique to remove hemicellulose. This could be a great alternative to chemical pretreatment in order to isolate the cellulose. Superheated steam is believed as the most economical pretreatment as compared to the other physical pretreatments as discussed before.

Superheated steam is unsaturated (dry) steam generated by the addition of heat to saturated (wet) steam [31]. It has several advantages such as improved energy efficiency, higher drying rate, being conducted at atmospheric pressure and reduced environmental impact when condensate is reused [32][33]. Saturated steam cannot be superheated when it is in contact with water which is also heated, and condensation of superheated steam cannot occur without being reduced to the temperature of saturated steam. It has a high heat transfer coefficient, enabling rapid and uniform heating. Drying rates with superheated steam are faster than those with conventional hot air. Steam in a dried state or superheated steam is assumed to behave like a perfect gas. Although superheated steam is considered a perfect gas, it possesses properties like those of gases namely pressure, volume, temperature, internal energy, enthalpy and entropy. The pressure, volume, and temperature of steam as a vapour is not connected by any simple relationship such as is expressed by the characteristic equation for a perfect gas. Figure 4 shows the schematic diagram of superheated steam pretreatment. The saturated steam was generated in the boiler. The saturated steam produced was further heated by a super-heater to produce superheated steam. Then, the superheated steam was subjected to the fibres.

Figure 4. Schematic design of superheated steam pretreatment. Reprinted with permission from ref. [31]. 2018 Universiti Putra Malaysia.

Superheated steam has been managed to alter the chemical composition of natural fibres. It has been proven that superheated steam pretreatment managed to remove high amount of hemicellulose from the lignocellulose fibres [34][35][36][37][38][39][40]. According to Warid et al. [40], superheated steam pretreatment on oil palm biomass at higher temperature and shorter time managed to remove a high amount of hemicellulose while maintaining the cellulose composition as compared to the method reported by Norrrahim et al. [39]. It was found that oil palm mesocarp fibre pretreated at 260 °C/30 min managed to remove hemicellulose of 68%, while cellulose degradation is maintained below 5%. Besides that, superheated steam was also able to remove silica bodies from the fibres where the presence of silica bodies increases the difficulty in grinding the fibre and causes abrasive wear and screw damage [32].

4.1.2. Hydrothermal

Hydrothermal treatment is another pretreatment that has been proven to effectively remove impurities such as hemicellulose, lignin, and silica from lignocellulosic biomass. This treatment is being widely used in industry, owing to its low cost of production, high effectiveness in removing impurities without affecting the cellulose structure, disorganizing hydrogen bonds, swelling of the lignocellulosic biomass, as well as minimum requirements of preparation and handling [41][42]. In contrast to the superheated steam system that uses steam as the main mechanism, hydrothermal pretreatment only relies on water that will be subjected to a high temperature during the whole processing [43]. This treatment is also considered as an autohydrolysis of lignocellulosic linkages, with the presence of hydronium ions (H3O+) generated from water and acetic groups released from hemicellulose. The hydronium ions (H3O+) will act as a catalyst to break down and loosen the lignocellulosic structure [41][44]. This then will improve the effectiveness of further treatments such as enzymatic hydrolysis for biosugar production [43] and anaerobic digestion for biomethane production [45].

Numerous studies have reported the effectiveness of this treatment in reducing impurities, especially at a very high temperature. Zhang et al. [46] studied the effects of different hydrothermal temperatures which were 170, 190, and 210 °C at 20 min pretreatment time on corn stover. This study reported a drastic reduction in hemicellulose with an increase in hydrothermal temperature. In fact, no content of hemicellulose was detected and almost 125% of lignin was removed after hydrothermal treatment at 210 °C. Similarly, Phuttaro et al. [47] also reported the same trend of results, in which no amount of hemicellulose was detected in Napier grass after pretreatet at 200 °C for 15 min. Both studies agreed that hydrothermal pretreatment plays a significant effect in improving the enzymatic hydrolysis yield afterwards. Meanwhile, Lee and Park [42] reported that sunflower biomass treated with hydrothermal pretreatment at 160–220 °C for 30 min demonstrated a reduction of hemicellulose and lignin up to 25 and 15%, respectively. This then led to higher methane yield (213.87–289.47 mL g−1) and biodegradability (43–63%) than the non-hydrothermally treated biomass. All of these reviews highlighted that despite of using a simple mechanism, hydrothermal can still efficiently removed impurities and improve the chemical and physical properties of lignocellulosic biomass prior to further treatments.

4.1.3. Steam Explosion

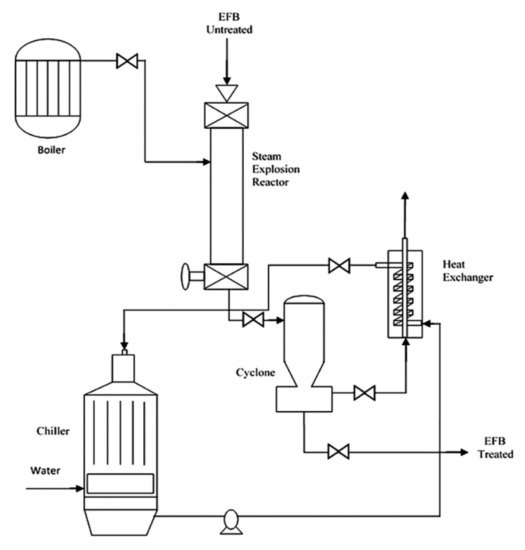

Steam explosion involves the use of high pressure and heat to pretreat lignocellulosic biomass. The biomass will be subjected to heat ranging from 160–280 °C and high pressure ranging from 0.2–5 MPa, depending on biomass source, duration, and other conditions [48][49]. Before the discovery of superheated steam and hydrothermal treatment, the steam explosion was widely applied in the industry due to its low energy consumption and chemical usage [49]. Figure 5 shows an example of the steam explosion process. Theoretically, biomass needs to be subjected to high temperature and pressure in a close reactor. The water contained in the biomass will then be evaporated and expanded, led to hydrolysis to a certain extent. Explosive decompression will then occur by promptly reducing the pressure to the atmospheric level [50][51].

Figure 5. Schematic diagram of steam explosion process. Page: 11 Reprinted with permission from ref. [51]. 2016 Elsevier.

Steam explosion treatment helps to reduce the particle size of biomass, disrupt the structure of lignocellulosic biomass by removing amorphous structures such as hemicellulose and other impurities, and reduce cellulose crystallinity [52]. Similar to hydrothermal, the steam explosion also carried out auto-hydrolysis. During processing, acetic acids and other organic acids will be formed, and this will assist in the breakdown of ester and ether bonds in the cellulose-hemicellulose-lignin matrix. For steam explosion, reaction temperature, pressure, and processing duration are considered as the key factors.

Numerous studies have reported the effectiveness of this treatment in reducing impurities and enhancing the effectiveness of further treatments. For example, Abraham et al. [52] discovered that the sudden pressure drop due to explosion has pre-defibrillated the raw banana, jute, and pineapple leaf fibre biomass after pretreated for 1 h, which then eases and enhances the efficiency of fibrillation process by acid hydrolysis for the production of nanocellulose. Meanwhile, Medina et al. [51] discovered an application of steam explosion pretreatment for empty fruit bunches. The heating time was around 2 min and the reaction time was controlled after the temperature was reached. It was found that the application of steam explosion helped to enhance the production of glucans to 34.69%, reduce the amount of hemicellulose to 68.11%, and increase enzymatic digestibility to 33%. This was all due to steam explosion pretreatment, which helped in increasing the fibre porosity of empty fruit bunches. Marques et al. [53] also highlighted that the oil palm mesocarp fibre which has been treated to the steam explosion has higher purity, thermal stability, and crystallinity than the non-treated biomass. The reaction time was between 3 to 17 min. The cellulose pulp yield was increased by 47%. In addition, high-quality lignin was obtained as a co-product of steam explosion pretreatment, which can potentially be used for other purposes such as in the development of resin.

4.2. Biological-Chemical Pretreatment

In recent years, a more often used combined pretreatment method is physical and chemical combined pretreatment, while biological and chemical combined pretreatment has yet to be thoroughly researched. Combining microbial and chemical pretreatments, for instance, is seen as a cost-effective technique for reducing pretreatment times, minimizing chemical usage and hence secondary pollution [54]. Table 3 listed different biological-chemical pretreatment approaches to pretreat lignocellulosic biomass. Till now, the biological-alkaline pretreatment for lignocellulosic biomass has been the most widely researched.

Table 3. Previous research on biological-chemical pretreatment approaches to pretreat lignocellulosic biomass. Data retrieved from Ref. [54].

| Substrate | Conditions | Component’s Degradation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Step | 2nd Step | Lignin | Hemicellulose | Cellulose | |

| Biological—alkaline pretreatment | |||||

| Corn stalks | Irpex lacteus (28 °C, 15 d) | 0.25 M NaOH solution (75 °C, 2 h) |

80 | 51.37 | 6.62 |

| Populus tomentosa | Trametes velutina D10149 (28 °C, 28 d) | 70% (v/v) ethanol aqueous solution containing 1%(w/v) NaOH (75 °C, 3 h) | 23.08 | 22.22 | 18.91 |

| Willow sawdust | Leiotrametes menziesii (27 °C, 30 d) | 1% (w/v) NaOH (80 °C, 24 h) | 59.8 | 68.1 | 51.2 |

| Abortiporus biennis (27 °C, 30 d) | 54.2 | 51.8 | 29.1 | ||

| Biological—acid pretreatment | |||||

| Populus tomentosa | Trametes velutina D1014 (28 °C, 56 d) | 1% sulphuric acid (140 °C, 1 h) | 23.82 | 75.96 | (+) 18.74 |

| Oil palm empty fruit bunches | Pleurotus floridanus LIPIMC996 (31 °C, 28 d) | Ball milled at 29.6/s for 4 min. Phosphoric acid treatment (50 °C, 5 h) | (+) 8.29 | 60.63 | (+) 37.52 |

| Olive tree biomass | Irpex lacteus (Fr.238 617/93) (30 °C, 28 d) | 2% w/v H2SO4 (130 °C, 1.5 h) | (+) 105.82 | 75.29 | (+) 62.95 |

| Biological—oxidative pretreatment | |||||

| Corn Straw | Echinodontium taxodii (25 °C, 15 d) | 0.0016% NaOH and 3% H2O2 (25 °C, 16 h) | 52.00 | 23.64 | (+) 45.45 |

| Hemp chips | Pleurotus eryngii (28 °C, 21 d) | 3% NaOH and 3% (v/v) H2O2 (40 °C, 24 h) | 55.7 | 23.2 | 25.1 |

| Biological—organosolv pretreatment | |||||

| Sugarcane straw | Ceriporiopsis subvermispora (27 °C, 15 d) | Acetosolv pulping (Acetic acid with 0.3% w/w HCl) (120 °C, 5 h | 86.8 | 93.8 | 32.1 |

| Pinus radiata | Gloeophyllum trabeum (27 °C, 28 d) | 60% ethanol in water solvent (200 °C, 1 h) | 74.26 | 80.74 | - |

| Biological—liquid hot water (LHW) pretreatment | |||||

| Soybean | Liquid Hot water (170 °C, 3 min, 400 rpm, 110 psi, solid to liquid ratio of 1:10) | Ceriporiopsis subvermispora (28 °C, 18 d) | 36.69 | 41.34 | 0.84 |

| Corn stover | 41.99 | 42.91 | 7.09 | ||

| Wheat straw | Hot water extraction (HWE) (85 °C, 10 min, solid to liquid ratio of 1:20) | Ceriporiopsis subvermispora (28 °C, 18 d) | 24.87 | 13.19 | 1.86 |

| Corn stover | 30.09 | 28.14 | 4.96 | ||

| Soybean | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||

| Biological—steam explosion pretreatment | |||||

| Beech woodmeal | Phanerochaete chrysosporium (37 °C, 28 d) | Steam explosion (215 °C, 6.5 min) | 42.00 | - | - |

| Sawtooth oak, corn and bran | Lentinula edodes (120 d) | Steam explosion (214 °C, 5 min, 20 atm) | 17.1 | 80.43 | (+) 5.19 |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polym13172971

References

- Aftab, M.N.; Iqbal, I.; Riaz, F.; Karadag, A.; Tabatabaei, M. Different Pretreatment Methods of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Use in Biofuel Production. In Biomass for Bioenergy-Recent Trends and Future Challenges; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019.

- Xiao, C.; Bolton, R.; Pan, W. Lignin from rice straw Kraft pulping: Effects on soil aggregation and chemical properties. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 1482–1488.

- Himmel, M.E.; Ding, S.-Y.; Johnson, D.K.; Adney, W.S.; Nimlos, M.R.; Brady, J.W.; Foust, T.D. Biomass Recalcitrance: Engineering Plants and Enzymes for Biofuels Production. Science 2007, 315, 804–807.

- Tu, W.-C.; Hallett, J.P. Recent advances in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 20, 11–17.

- Nurazzi, N.M. Treatments of natural fiber as reinforcement in polymer composites—A short review. Funct. Compos. Struct. 2021, 3, 2.

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ilyas, R.A.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Rani, M.S.A.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Shazleen, S.S. Chemical Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass for the Production of Bioproducts: An Overview. Appl. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2021.

- Williams, C.L.; Emerson, R.M.; Tumuluru, J.S. Biomass Compositional Analysis for Conversion to Renewable Fuels and Chemicals. In Biomass Volume Estimation and Valorization for Energy; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2017.

- Mood, S.H.; Golfeshan, A.H.; Tabatabaei, M.; Jouzani, G.S.; Najafi, G.; Gholami, M.; Ardjmand, M. Lignocellulosic biomass to bioethanol, a comprehensive review with a focus on pretreatment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 77–93.

- Guerriero, G.; Hausman, J.F.; Strauss, J.; Ertan, H.; Siddiqui, K.S. Lignocellulosic biomass: Biosynthesis, degradation, and industrial utilization. Eng. Life Sci. 2016, 16, 1–16.

- Barakat, A.; De Vries, H.; Rouau, X. Dry fractionation process as an important step in current and future lignocellulose biorefineries: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 134, 362–373.

- Chen, H.; Liu, J.; Chang, X.; Chen, D.; Xue, Y.; Liu, P.; Lin, H.; Han, S. A review on the pretreatment of lignocellulose for high-value chemicals. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 160, 196–206.

- Koupaie, E.h.; Dahadha, S.; Lakeh, A.A.B.; Azizi, A.; Elbeshbishy, E. Enzymatic pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for enhanced biomethane production-A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 774–784.

- Haldar, D.; Purkait, M.K. A review on the environment-friendly emerging techniques for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass: Mechanistic insight and advancements. Chemosphere 2021, 264, 128523.

- Zadeh, Z.E.; Abdulkhani, A.; Aboelazayem, O.; Saha, B. Recent Insights into Lignocellulosic Biomass Pyrolysis: A Critical Review on Pretreatment, Characterization, and Products Upgrading. Processes 2020, 8, 799.

- Mahmood, H.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Iqbal, T.; Khan, M.J. Recent advances in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels and value-added products. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 20, 18–24.

- Hassan, S.; Williams, G.A.; Jaiswal, A.K. Emerging technologies for the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 262, 310–318.

- Kumar, A.K.; Sharma, S. Recent updates on different methods of pretreatment of lignocellulosic feedstocks: A review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 1–19.

- Karunanithy, C.T.; Muthukumarappan, K. Influence of Extruder Temperature and Screw Speed on Pretreatment of Corn Stover while Varying Enzymes and Their Ratios. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2010, 162, 264–279.

- Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Pan, X.; Gleisner, R. Specific surface to evaluate the efficiencies of milling and pretreatment of wood for enzymatic saccharification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2009, 64, 474–485.

- Hideno, A.; Inoue, H.; Tsukahara, K.; Fujimoto, S.; Minowa, T.; Inoue, S.; Endo, T.; Sawayama, S. Wet disk milling pretreatment without sulfuric acid for enzymatic hydrolysis of rice straw. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 2706–2711.

- Bussemaker, M.J.; Zhang, D. Effect of Ultrasound on Lignocellulosic Biomass as a Pretreatment for Biorefinery and Biofuel Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 3563–3580.

- Gogate, P.R.; Sutkar, V.S.; Pandit, A.B. Sonochemical reactors: Important design and scale up considerations with a special emphasis on heterogeneous systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 166, 1066–1082.

- Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Jawaid, M.; Pruncu, C.I.; Khan, A. A comprehensive review of techniques for natural fibers as reinforcement in composites: Preparation, processing and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 207, 108–121.

- Bleuze, L.; Lashermes, G.; Alavoine, G.; Recous, S.; Chabbert, B. Tracking the dynamics of hemp dew retting under controlled environmental conditions. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018, 123, 55–63.

- Fila, G.; Manici, L.M.; Caputo, F. In vitro evaluation of dew-retting of flax by fungi from southern Europe. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2001, 138, 343–351.

- Repečkiene, J.; Jankauskiene, Z. Application of fungal complexes to improve flax dew-retting. Biomed. Moksl. 2009, 83, 63–71.

- Jankauskiene, Z.; Lugauskas, A.; Repeckiene, J. New Methods for the Improvement of Flax Dew Retting. J. Nat. Fibers 2007, 3, 59–68.

- Liu, M.; Ale, M.T.; Kołaczkowski, B.; Fernando, D.; Daniel, G.; Meyer, A.S.; Thygesen, A. Comparison of traditional field retting and Phlebia radiata Cel 26 retting of hemp fibres for fibre-reinforced composites. AMB Express 2017, 7, 1–15.

- Fernando, D.; Thygesen, A.; Meyer, A.S.; Daniel, G. Elucidating field retting mechanisms of hemp fibres for biocomposites: Effects of microbial actions and interactions on the cellular micro-morphology and ultrastructure of hemp stems and bast fibres. BioResources 2019, 14, 4047–4084.

- Farid, M.A.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Roslan, A.M.; Ariffin, H.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Othman, M.R.; Yoshihito, S. Improving the decolorization of glycerol by adsorption using activated carbon derived from oil palm biomass. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 27976–27987.

- Norrrahim, M.N.F. Superheated Steam Pretreatment of Oil Palm Biomass for Improving Nanofibrillation of Cellulose and Performance of Polypropylene/Cellulose Nanofiber Composites. Doctoral Thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia, 2018.

- Nordin, N.I.A.A.; Ariffin, H.; Andou, Y.; Hassan, M.A.; Shirai, Y.; Nishida, H.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Karuppuchamy, S.; Ibrahim, N.A. Modification of Oil Palm Mesocarp Fiber Characteristics Using Superheated Steam Treatment. Molecules 2013, 18, 9132–9146.

- Sharip, N.S.; Ariffin, H.; Hassan, M.A.; Nishida, H.; Shirai, Y. Characterization and application of bioactive compounds in oil palm mesocarp fiber superheated steam condensate as an antifungal agent. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 84672–84683.

- Megashah, L.N.; Ariffin, H.; Zakaria, M.R.; Hassan, M.A.; Andou, Y.; Padzil, F.N.M. Modification of cellulose degree of polymerization by superheated steam treatment for versatile properties of cellulose nanofibril film. Cellulose 2020, 27, 7417–7429.

- Bahrin, E.K.; Baharuddin, A.S.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Razak, M.N.A.; Sulaiman, A.; Aziz, S.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Shirai, Y.; Nishida, H. Physicochemical property changes and enzymatic hydrolysis enhancement of oil palm empty fruit bunches treated with superheated steam. BioResources 2012, 7, 1784–1801.

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ariffin, H.; Hassan, M.A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Nishida, H. Utilisation of superheated steam in oil palm biomass pretreatment process for reduced chemical use and enhanced cellulose nanofibre production. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 16, 668.

- Norrrahim, M.; Ariffin, H.; Yasim-Anuar, T.; Hassan, M.; Ibrahim, N.; Yunus, W.; Nishida, H. Performance Evaluation of Cellulose Nanofiber with Residual Hemicellulose as a Nanofiller in Polypropylene-Based Nanocomposite. Polymers 2021, 13, 1064.

- Zakaria, M.R.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Hirata, S.; Hassan, M.A. Hydrothermal and wet disk milling pretreatment for high conversion of biosugars from oil palm mesocarp fiber. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 181, 263–269.

- Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Ariffin, H.; Yasim-Anuar, T.A.T.; Ghaemi, F.; Hassan, M.A.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Ngee, J.L.H.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W. Superheated steam pretreatment of cellulose affects its electrospinnability for microfibrillated cellulose production. Cellulose 2018, 25, 3853–3859.

- Warid, M.N.M.; Ariffin, H.; Hassan, M.A.; Shirai, Y. Optimization of Superheated Steam Treatment to Improve Surface Modification of Oil Palm Biomass Fiber. Bioresources 2016, 11, 5780–5796.

- Lei, H.; Cybulska, I.; Julson, J. Hydrothermal Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass and Kinetics. J. Sustain. Bioenergy Syst. 2013, 3, 250–259.

- Lee, J.; Park, K.Y. Impact of hydrothermal pretreatment on anaerobic digestion efficiency for lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of pretreatment temperature on the formation of biomass-degrading byproducts. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127116.

- Zakaria, M.R.; Hirata, S.; Hassan, M.A. Hydrothermal pretreatment enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis and glucose production from oil palm biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 176, 142–148.

- Rasmussen, H.; Sørensen, H.R.; Meyer, A.S. Formation of degradation compounds from lignocellulosic biomass in the biorefinery: Sugar reaction mechanisms. Carbohydr. Res. 2014, 385, 45–57.

- Bianco, F.; Şenol, H.; Papirio, S. Enhanced lignocellulosic component removal and biomethane potential from chestnut shell by a combined hydrothermal–alkaline pretreatment. Sci. Total. Environ. 2021, 762, 144178.

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Huang, G.; Yang, Z.; Han, L. Understanding the synergistic effect and the main factors influencing the enzymatic hydrolyzability of corn stover at low enzyme loading by hydrothermal and/or ultrafine grinding pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 264, 327–334.

- Phuttaro, C.; Sawatdeenarunat, C.; Surendra, K.; Boonsawang, P.; Chaiprapat, S.; Khanal, S.K. Anaerobic digestion of hydrothermally-pretreated lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of pretreatment temperatures, inhibitors and soluble organics on methane yield. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 284, 128–138.

- Megashah, L.N. Development of Efficient Processing Method for the Production of Cellulose Nanofibrils from Oil Palm Biomass. Doctoral Thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia, 2020.

- Sarker, T.R.; Pattnaik, F.; Nanda, S.; Dalai, A.K.; Meda, V.; Naik, S. Hydrothermal pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass: A review of steam explosion and subcritical water hydrolysis. Chemosphere 2021, 284, 131372.

- Marques, F.P.; Soares, A.K.L.; Lomonaco, D.; e Silva, L.M.A.; Santaella, S.T.; Rosa, M.D.F.; Leitão, R.C. Steam explosion pretreatment improves acetic acid organosolv delignification of oil palm mesocarp fibers and sugarcane bagasse. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 175, 304–312.

- Medina, J.D.C.; Woiciechowski, A.; Filho, A.Z.; Nigam, P.S.; Ramos, L.P.; Soccol, C.R. Steam explosion pretreatment of oil palm empty fruit bunches (EFB) using autocatalytic hydrolysis: A biorefinery approach. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 199, 173–180.

- Abraham, E.; Deepa, B.; Pothan, L.A.; Jacob, M.; Thomas, S.; Cvelbar, U.; Anandjiwala, R. Extraction of nanocellulose fibrils from lignocellulosic fibres: A novel approach. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1468–1475.

- Marques, F.P.; Silva, L.M.A.; Lomonaco, D.; Rosa, M.D.F.; Leitão, R.C. Steam explosion pretreatment to obtain eco-friendly building blocks from oil palm mesocarp fiber. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2020, 143, 111907.

- Meenakshisundaram, S.; Fayeulle, A.; Leonard, E.; Ceballos, C.; Pauss, A. Fiber degradation and carbohydrate production by combined biological and chemical/physicochemical pretreatment methods of lignocellulosic biomass—A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 331, 125053.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!