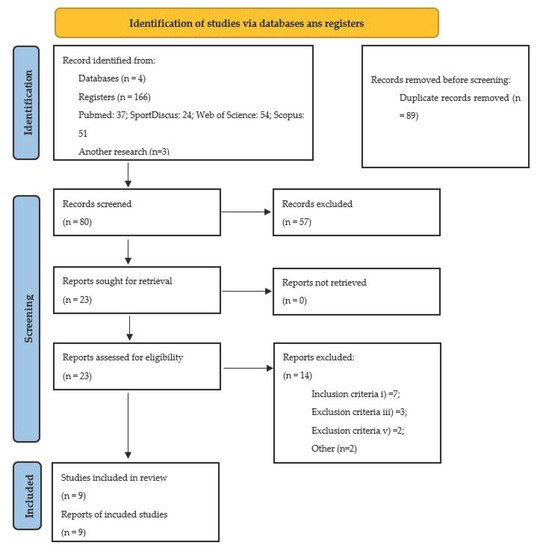

The present systematic review aims to analyze the effects of ST in individuals with ID, based on the characterization of several programs implemented, as well as the identification of mean characteristics for ST prescription programs, namely duration, weekly frequency, appropriate assessment methods, and type of exercises. The following subsections will discuss all main point of the ST programs applied.

3,7. Exercises

According to the studies evaluated [40,43,45–47], most ST programs included exercises targeting the main muscle groups in each session. Although the studies analyzed use different types of equipment (weight training machines, using resistance elastics, and/or ankle weights), all of them show intentionality to use ST exercises aiming to request the main muscle group [50]. It should be noted that only two studies used a period of adaptation and familiarization to the prescribed exercises [52,53], which is important to eliminate the fear of using new materials, movement perception, and to ensure high quality results. The most common exercises used in the ST programs are the leg flexion and leg extension exercises (hamstrings and quadriceps), the abdominals in their different variants (abdomen muscles), the chest press (pectoral major), the low row or the lat pull down (latissimus dorsi), flexion of the forearm (biceps), an extension of the forearm (triceps), and elevation, abduction, or shoulder press (deltoids). When prescribing six to eight exercises, ST programs were in accordance with the recommendations provided by ACSM [48], however, in some studies, this was not the case [40,42]. In the majority of the studies, selected exercises tended to be simple and easy to be performed, with special attention and reinforcement in the instruction, demonstration, and familiarization [48,52,53]. Some individuals may experience difficulties in controlling movement, particularly in the eccentric phase, and thus it was suggested to use machines that help to better control them (for example, a chest press device rather than the bench press). Additionally, machine exercises are preferable to avoid some type of injury, for presenting a smaller range of motion; however, there were some exceptions such as the biceps curl, seen as working well in participants with ID [50].

3,8. ST Programs Outcomes

Some studies have shown significant positive effects on muscle strength in lower limbs [46], in upper and lower limbs [47], and in handgrip strength (p < 0.0001) [43]. These results are very encouraging for further studies with this population and to implement in clinical practice. A greater capacity to generate strength by the muscles (lower and upper limbs) may become an essential tool to insert these patients in professional activities due to the increase in their physical capacities [46].

Other studies found an increase in fat-free mass and a reduction in fat mass [42–44]. Depending on the aims and evaluation methods used, some studies reported a reduction in the waist circumference [44] of the BMI [43] and an improvement in balance [40].

An increase in the concentration of salivary immunoglobulin, testosterone levels, plasma leptin levels, TNF- , and IL-6 was also found. Specifically, Fornieles et al. [39] showed thar resistance training program of 12 weeks increased concentration of salivary immunoglobulin (p = 0.0120), testosterone levels (p = 0.0088) and task performance (p = 0.0141). This study highlights the benefits of ST, as this increase in salivary IgA levels can prevent respiratory tract infections in individuals with DS [54]. This study also shows an improvement in the anabolic status of DS patients after the ST program, as cortisol levels remain unchanged and there was an increase in salivary testosterone. It was also found

that the improvement of task performance is of great interest to this population. Having improved levels of muscle strength may allow this population to perform a greater number of activities and continue to exercise, thus reducing the risk of secondary consequences for their health [55,56]. Additionally, improvements in the response to systemic inflammation, in the antioxidant defense system, and a reduction in oxidative damage were also reported [39,44,45].

Dynamic balance as a parameter of functional capacity is also limited in individuals with ID. Even so, two studies reported improvements with ST, particularly in exercises focused to improve strength and power of the lower limbs [40,46]. These improvements were also associated with improvements in gait speed and balance [46]. Other non-randomized controlled studies have shown interesting results through the implementation of ST programs in individuals with ID, namely, cognitive effects such as positive changes in working memory, short-term memory, vocabulary knowledge, and reasoning ability [57], and improved flexibility [58] and performance in daily life activities [59]. There is an urgent need for randomized procedures to assess the benefits of these variables and aerobic capacity. Several studies have found significant differences in body composition parameters after the strength training program, namely a reduction in the BMI (p < 0.0001) and the skin fold of the calf (p = 0.008) [43]; a decreased in waist circumference (p = 0.0416) and increase in the fat-free mass (p = 0.011) [44]; and an increased in the lean mass (p = 0.008) and reduction in the fat percentage (p = 0.036) [43]. Since being overweight and obesity are associated with poor health and quality of life, these results show that strength training is a good intervention to reduce these values.

With the implementation of ST programs, despite the different prescriptions, positive results were verified in terms of the aims defined in all studies, which shows how training variables, techniques, and methods (for example, training frequency and exercise selection volume, training load and repetitions, and others), can be manipulated to optimize training response. The different results presented in Table 4 and of the non-randomized controlled studies [57–59] are demonstrated due to the different aims and evaluation methods used in each study, being an added value the application of ST, since it can have this wide range of benefits. All these results are important in terms of promoting the quality of life of individuals with ID, related to the conceptual model of Schalock et al. [60], a construct divided into three dimensions: (i) independence; (ii) social participation; (iii) well-being.

Some studies included in the systematic review have some limitations, which may limit the magnitude of the results. Future studies should take them into account when implementing ST programs: (i) short-term studies [39,44,47]; (ii) no follow up to determine whether the positive effects were maintained [39,44,45,47]; (iii) small sample size [41]; (iv) sample size only boys [41]; (v) exclusion of children with severe and profound ID [41]; (vi) a small number of professionals to supervise the exercises produced in the experimental protocol [42]; (vii) lack of more accurate measurements to evaluate; and (viii) a small number of outcomes [47].

At the same time, future studies are suggested to apply the assessment of body composition variables by electrical bioimpedance, such as the phase angle, since it has been considered a relevant marker of health status [61]. Moreover, a higher phase angle value is positively associated with a higher quality of cell membranes [62], while a lower value is associated with deterioration, which can compromise all cell functions [62]. Thus, phase angle assessment would be helpful to understand if there are adaptations with ST in this variable that has a strong correlation with cell health and integrity, being an excellent indicator of the capacity of the cell membrane to retain liquids, fluids, and nutrients in the population with ID.

The fact that ID is a multisystem and complex disorder characterized by the presence of delays or deficits in the development of adaptive behavior comprising conceptual, social, and motor skills may support a possible explanation why results could differ between studies and studies without the RCT method. The effects of the interventions in the various studies appear similar to those that have been reported following resistance training in the average healthy and intellectually disabled population [3,22,25,30,33]. However, some variability has also been reported in other resistance training studies and those examining other exercise modalities [20,29,46,47,57]. Inherent within any measurement are both technical error and random within-subject variation [63]. Studies included in this systematic review have shown that, although using different training intensities, it was possible to identify improvements in the variables under study; however, it is noted that, before starting the training program, it is necessary to carry out strength assessments, either through RMtests, using devices, or isokinetic, as recommended by ACSM [48], to determine the correct intensity to be used. During this strength assessment process, as during training, RM tests using free weights, push-ups, and pull-ups should be avoided [48] to prevent any type of injury. Moreover, familiarization with the assessment procedures, a practical demonstration of execution, simple instructions, constant supervision, and verbal and visual reinforcement are necessary [48,53] for greater success in the didactic-pedagogical

process.

This systematic review analyzed the effects of ST in individuals with intellectual disability, aiming to be a reference guidelines tool for researchers and professionals of PE. The analyzed studies show characteristics and recommendations that professionals can follow when implementing an ST program to promote benefits and positive outcomes, namely, the maintenance of/increase in physical fitness, quality of life, and health, thus decreasing the risk of developing chronic diseases, being the strong aspect of this systematic review. Therefore, it is essential to implement this type of ST program, incorporated into the weekly routine of this population, which, when associated with an appropriate lifestyle, causes a set of adaptations and benefits and, ultimately, can promote a decrease in clinical expenses, an increase in healthy aging, and better health.

It is recommended to increase the implementation of ST programs in the target population, expanding the knowledge in terms of the methods, structure, and duration used, so that professionals can prescribe adapted and effective ST programs. At the same time, it is important that the exercise professionals have an in-depth knowledge of the individual, their comorbidities, limitations, and preferences, before prescribing and starting a PE program [50].

Despite the relevance of the selected clinical trials for the preparation of this systematic review, some limitations can be observed: (1) the diversified intervention methodology, involving different strengths, intensities, volumes, and weekly training exercise programs; (2) unclear descriptions of the process of randomization and allocation of people with ID in the groups; (3) loss of follow-up; (4) different evaluation methodologies, as well as the results, not allowing a further discussion as well as a meta-analysis about the effects produced by the several ST programs applied; (5) the level of ID was not mentioned in all studies included, which limits the generalization of the results and suggests that future studies should mention such specificity.