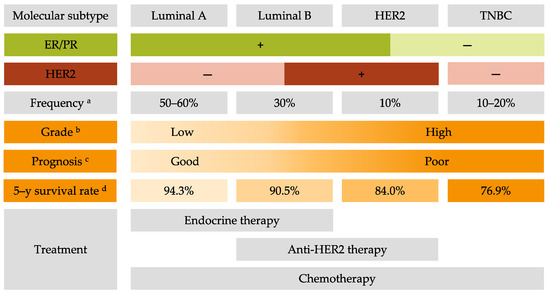

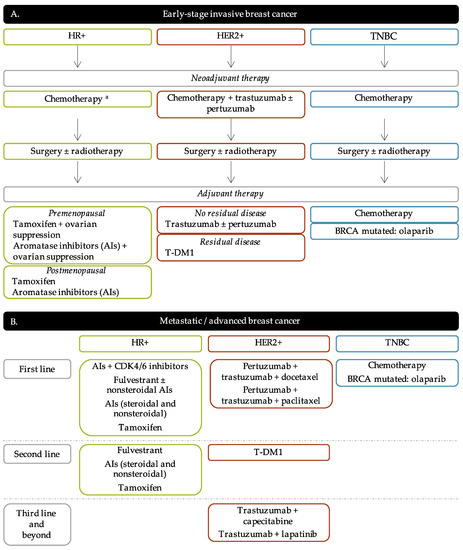

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequent cancer diagnosed in women worldwide. This heterogeneous disease can be classified into four molecular subtypes (luminal A, luminal B, HER2 and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)) according to the expression of the estrogen receptor (ER) and the progesterone receptor (PR), and the overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Current BC treatments target these receptors (endocrine and anti-HER2 therapies) as a personalized treatment. Along with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, these therapies can have severe adverse effects and patients can develop resistance to these agents. Moreover, TNBC do not have standardized treatments. Hence it is essential to develop new treatments to target more effectively each BC subgroup.

- breast cancer

- personalized therapies

- molecular subtypes

- breast cancer treatment

- luminal

- HER2

- TNBC

1. Introduction

2. Common Treatments for All Breast Cancer Subtypes

2.1. Surgery

2.2. Radiotherapy

2.3. Chemotherapy

3. Current Personalized Treatments for Breast Cancer: Strengths and Weaknesses

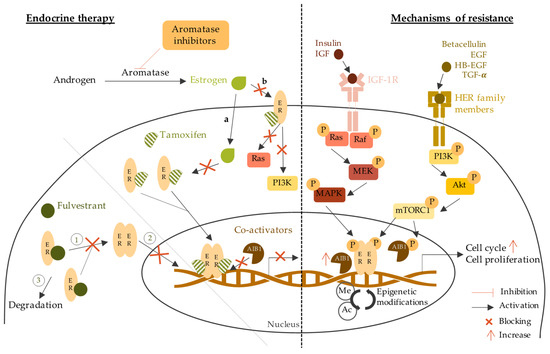

3.1. Endocrine Therapy

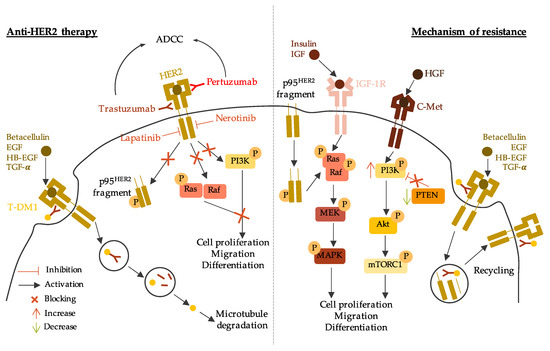

3.2. Anti-HER2 Therapy

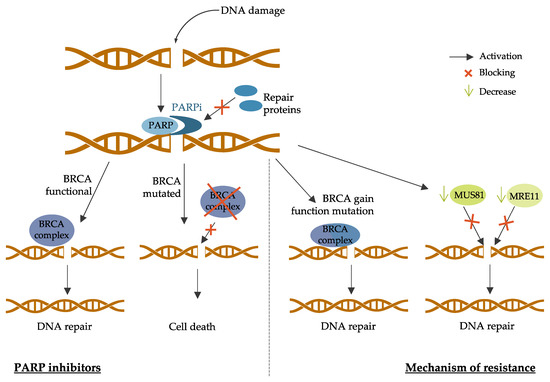

3.3. PARP Inhibitors

4. New Strategies and Challenges for Breast Cancer Treatment

4.1. Emerging Therapies for HR-Positive Breast Cancer

|

Targeted Therapy |

Drug Name |

Trial Number |

Patient Population |

Trial Arms |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pan-PI3K inhibitors |

Buparlisib |

BELLE-2 Phase III NCT01610284 [41] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Locally advanced or MBC Prior AI treatment |

Buparlisib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 6.9 months vs. 5.0 months (HR 0.78; p = 0.00021) PFS 6.8 months vs. 4.0 months in PI3K mutated (HR 0.76; p = 0.014) |

|

BELLE-3 Phase III NCT01633060 [42] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Locally advanced or MBC Prior endocrine therapy or mTOR inhibitors |

Buparlisib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 3.9 months vs. 1.8 months (HR 0.67; p = 0.0003) |

||

|

BELLE-4 Phase II/III NCT01572727 [43] |

HER2- Locally advanced or MBC No prior chemotherapy |

Buparlisib + pacliatxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel |

PFS 8.0 months vs. 9.2 months (HR 1.18, 95% CI 0.82–1.68) PFS 9.1 months vs. 9.2 months in PI3K mutated (HR 1.17, 95% 0.63–2.17) |

||

|

Pictilisib |

FERGI Phase II NCT01437566 [44] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Prior AI treatment |

Pictilisib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 6.6 months vs. 5.1 months (HR 0.74; p = 0.096) PFS 6.5 months vs. 5.1 months in PI3K mutated (HR 0.74; p = 0.268) PFS 5.8 months vs. 3.6 months in non-PI3K mutated (HR 0.72; p = 0.23) |

|

|

PEGGY Phase II NCT01740336 [45] |

HR+/HER2- Locally recurrent or MBC |

Pictilisib + paclitaxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel |

PFS 8.2 months vs. 7.8 months (HR 0.95; p = 0.83) PFS 7.3 months vs. 5.8 months in PI3K mutated (HR 1.06; p = 0.88) |

||

|

Isoform-specific inhibitors |

Alpelisib |

Phase Ib NCT01791478 [46] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal MBC Prior endocrine therapy |

Alpelisib + letrozole |

CBR 35% (44% in patients with PIK3CA mutated and 20% in PIK3CA wild-type tumors; 95% CI [17%; 56%]) |

|

SOLAR-1 Phase III NCT02437318 [47] |

HR+/HER2- Advanced BC Prior endocrine therapy |

Alpelisib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 7.4 months vs. 5.6 months in non-PI3K mutated (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.58–1.25) PFS 11.0 months vs. 5.7 months in PI3K mutated (HR 0.65; p = 0.00065) |

||

|

NEO-ORB Phase II NCT01923168 [48] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Early-stage BC Neoadjuvant setting |

Alpelisib + letrozole vs. placebo + letrozole |

ORR 43% vs. 45% (PIK3CA mutant), 63% vs. 61% (PIK3CA wildtype) pCR rates low in all groups |

||

|

Taselisib |

SANDPIPER Phase III NCT02340221 [49] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Locally advanced or MBC PIK3CA-mutant Prior AI treatment |

Taselisib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 7.4 months vs. 5.4 months (HR 0.70; p = 0.0037) |

|

|

LORELEI Phase II NCT02273973 [50] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Early-stage BC Neoadjuvant setting |

Taselisib + letrozole vs. placebo + letrozole |

ORR 50% vs. 39.3% (OR 1.55; p = 0.049) ORR 56.2% vs. 38% in PI3K mutated (OR 2.03; p = 0.033) No significant difference in pCR |

||

|

mTOR inhibitors |

Everolimus |

BOLERO-2 Phase III NCT00863655 [51] |

HR+/HER2- Advanced BC Prior AI treatment |

Everolimus + exemestane vs. placebo + exemestane |

PFS 6.9 months vs. 2.8 months (HR 0.43; p < 0.001) |

|

TAMRAD Phase II NCT01298713 [52] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal MBC Prior AI treatment |

Everolimus + tamoxifen vs. tamoxifen alone |

CBR 61% vs. 42% TTP 8.6 months vs. 4.5 months (HR 0.54) |

||

|

PrE0102 Phase II NCT01797120 [53] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal MBC Prior AI treatment |

Everolimus + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 10.3 months vs. 5.1 months (HR 0.61; p = 0.02) CBR 63.6% vs. 41.5% (p = 0.01) |

||

|

Akt inhibitors |

Capivasertib |

FAKTION Phase II NCT01992952 [54] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Locally advanced or MBC Prior AI treatment |

Capivasertib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 10.3 months vs. 4.8 months (HR 0.57; p = 0.0035) |

|

Phase I NCT01226316 [55] |

ER+ AKT1E17K-mutant MBC Prior endocrine treatment |

Capivasertib + fulvestrant vs. Capivasertib alone |

CBR 50% vs. 47% ORR 6% (fulvestrant-pretreated) and 20% (fulvestrant-naïve) vs. 20% |

||

|

CDK4/6 inhibitors |

Palcociclib |

PALOMA-1 Phase II NCT00721409 [56] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Advanced BC No prior systemic treatment |

Palbocilib + letrozole vs. letrozole alone |

PFS 20.2 months vs. 10.2 months (HR 0.488; p = 0.0004) PFS 26.1 months vs. 5.7 months (HR 0.299; p < 0.0001) in non-Cyclin D1 amplified PFS 18.1 months vs. 11.1 months (HR 0.508; p = 0.0046) in Cyclin D1 amplified |

|

PALOMA-2 Phase III NCT01740427 [57] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Advanced BC No prior systemic treatment |

Palbocilib + letrozole vs. placebo + letrozole |

PFS 24.8 months vs. 14.5 months (HR 0.58; p < 0.001) |

||

|

PALOMA-3 Phase III NCT01942135 [58] |

HR+/HER2- MBC Prior endocrine therapy |

Palbociclib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 9.5 months vs. 4.6 months (HR 0.46; p < 0.0001) |

||

|

Ribociclib |

MONALEESA-2 Phase III NCT01958021 [59] |

HR+/HER2- Postmenopausal Advanced or MBC |

Ribociclib + letrozole vs. placebo + letrozole |

PFS 25.3 months vs. 16.0 months (HR 0.568; p < 0.0001) |

|

|

MONALEESA-3 Phase III NCT02422615 [60] |

HR+/HER2- Advanced BC No prior treatment or prior endocrine therapy |

Ribociclib + fulvestrant vs. placebo + fulvestrant |

PFS 20.5 months vs. 12.8 months (HR 0.593; p < 0.001) |

||

|

Abemaciclib |

MONARCH-2 Phase III NCT02107703 [61] |

HR+/HER2- Advanced or MBC Prior endocrine treatment |

Abemaciclib + fulvestrant vs. fulvestrant alone |

PFS 16.4 months vs. 9.3 months (HR 0.553; p < 0.001) |

|

|

MONARCH-3 Phase III NCT02246621 [62] |

HR+/HER2- Advanced or MBC Prior endocrine treatment |

Abemaciclib + anastrozole or letrozole vs. placebo + anastrozole or letrozole |

PFS 28.18 months vs. 14.76 months (HR 0.546; p < 0.0001) |

HR+: hormone receptors positive; HER2-: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative; MBC: metastatic breast cancer; BC: breast cancer; PFS: progression free survival; CBR: clinical benefit rate; ORR: objective response rate; pCR: pathologic complete response; HR: hazard ratio.

4.2. New Strategic Therapies for HER2-Positive Breast Cancer

|

Targeted Therapy |

Drug Name |

Trial Number |

Patient Population |

Trial Arms |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antibodies drug conjugate (ADC) |

Trastuzumab-deruxtcan (DS-8201a) |

DESTINY-Breast01 Phase II NCT03248492 [64] |

HER2+ MBC Prior trastuzumab-emtansine treatment |

Trastuzumab-deruxtcan monotherapy |

PFS 16.4 months |

|

Trastuzumab-duocarmycin (SYD985) |

Phase I dose-escalation and dose-expansion NCT02277717 [65] |

HER2+ Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors |

Trastuzumab-duocarmycin monotherapy |

ORR 33% |

|

|

Modified antibodies |

Margetuxumab (MGAH22) |

SOPHIA Phase III NCT02492711 [66] |

HER2+ Advanced or MBC Prior anti-HER2 therapies |

Margetuximab + chemotherapy vs. trastuzumab + chemotherapy |

PFS 5.8 months vs. 4.9 months (HR 0.76; p = 0.03) OS 21.6 months vs. 19.8 months (HR 0.89; p = 0.33) ORR 25% vs. 14% (p < 0.001) |

|

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

Tucatinib |

HER2CLIMB Phase II NCT02614794 [67] |

HER2+ Locally advanced or MBC Prior anti-HER2 therapies |

Tucatinib + trastuzumab and capecitabine vs. placebo + trastuzumab and capecitabine |

PFS 33.1% (7.8 months) vs. 12.3% (5.6 months) (HR 0.54; p < 0.001) PFS 24.9% vs. 0% (HR 0.48; p < 0.001) in brain metastases patients OS 44.9% vs. 26.6% (HR 0.66; p = 0.005) |

|

Poziotinib |

NOV120101-203 Phase II NCT02418689 [68] |

HER2+ MBC Prior chemotherapy and trastuzumab |

Poziotinib monotherapy |

PFS 4.04 months |

|

|

HER2-derived peptide vaccine |

E75 (NeuVax) |

Phase I/II NCT00841399 NCT00854789 [69] |

HER2+ Node-positive or high-risk node-negative BC HLA2/3+ |

E75 vaccination vs. non-vaccination |

DFS 89.7% vs. 80.2% (p = 0.008) DFS 94.6% in optimal dosed patients (p = 0.005 vs. non-vaccination) |

|

GP2 |

Phase II NCT00524277 [70] |

HER2 (IHC 1-3+) Disease free Node-positive or high-risk node-negative BC HLA2+ |

GP2 + GM-CSF vs. GM-CSF alone |

DFS 94% vs. 85% (p = 0.17) DFS 100% vs. 89% in HER2-IHC3+ (p = 0.08) |

|

|

AE37 |

Phase II NCT00524277 [71] |

HER2 (IHC 1-3+) Node-positive or high-risk node-negative BC |

AE37 + GM-CSF vs. GM-CSF alone |

DFS 80.8% vs. 79.5% (p = 0.70) DFS 77.2% vs. 65.7% (p = 0.21) HER2-low DFS 77.7% vs. 49.0% (p = 0.12) TNBC |

|

|

PI3K inhibitors |

Alpelisib |

Phase I NCT02167854 [72] |

HER2+ MBC with a PIK3CA mutation Prior ado-trastuzumab emtansine and pertuzumab |

Alpelisib + Trastuzumab + LJM716 |

Toxicities limited drug delivery 72% for alpelisib 83% for LJM716 |

|

Phase I NCT02038010 [73] |

HER2+ MBC Prior trastuzumab-based therapy |

Alpelisib + T-DM1 |

PFS 8.1 months ORR 43% CBR 71% and 60% in prior T-DM1 patients |

||

|

Copanlisib |

PantHER Phase Ib NCT02705859 [74] |

HER2+ Advanced BC Prior anti-HER2 therapies |

Copanlisib + trastuzumab |

Stable disease 50% |

|

|

mTOR inhibitors |

Everolimus |

BOLERO-1 Phase III NCT00876395 [75] |

HER2+ Locally advanced BC No prior treatment |

Everolimus + trastuzumab vs. placebo + trastuzumab |

PFS 14.95 months vs. 14.49 months (HR 0.89; p = 0.1166) PFS 20.27 months vs. 13.03 months (HR 0.66; p = 0.0049) |

|

BOLERO-3 Phase III NCT01007942 [76] |

HER2+ Advanced BC Trastuzumab-resistant Prior taxane therapy |

Everolimus + trastuzumab and vinorelbine vs. placebo + trastuzumab and vinorelbine |

PFS 7.00 months vs. 5.78 months (HR 0.78; p = 0.0067) |

||

|

CDK4/6 inhibitors |

Palbociclib |

SOLTI-1303 PATRICIA Phase II NCT02448420 [77] |

HER2+ ER+ or ER- MBC Prior standard therapy including trastuzumab |

Palbociclib + trastuzumab |

PFS 10.6 months (luminal) vs. 4.2 months (non-luminal) (HR 0.40; p = 0.003) |

|

Ribociclib |

Phase Ib/II NCT02657343 [78] |

HER2+ Advanced BC Prior treatment with trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and trastuzumab emtansine |

Ribociclib + trastuzumab |

PFS 1.33 months No dose-limiting toxicities |

|

|

Abemaciclib |

MonarcHER Phase II NCT02675231 [79] |

HER2+ Locally advanced or MBC Prior anti-HER2 therapies |

Abemaciclib + trastuzumab and fulvestrant (A) vs. abemaciclib + trastuzumab (B) vs. standard-of-care chemotherapy + trastuzumab (C) |

PFS 8.3 months (A) vs. 5.7 months (C) (HR 0.67; p = 0.051) PFS 5.7 months (B) vs. 5.7 months (C) (HR 0.97; p = 0.77) |

HER2+: human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive; ER+: estrogen receptor positive; HLA2/3: human leucocyte antigen 2/3; MBC: metastatic breast cancer; BC: breast cancer; PFS: progression free survival; CBR: clinical benefit rate; ORR: objective response rate; DFS: disease-free survival OS: overall survival GM-CSF: granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulated factor; HR: hazard ratio.

4.3. Emerging Therapies for Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC)

|

Targeted Therapy |

Drug Name |

Trial Number |

Patient Population |

Trial Arms |

Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antibodies Drug Conjugate |

Sacituzumab govitecan |

ASCENT Phase III NCT02574455 [81] |

TNBC MBC Prior standard treatment |

Sacituzumab govitecan vs. single-agent chemotherapy |

PFS 5.6 months vs. 1.7 months (HR 0.41; p < 0.001) PFS 12.1 months vs. 6.7 months (HR 0.48; p < 0.001) |

|

VEGF inhibitors |

Bevacizumab |

BEATRICE Phase III NCT00528567 [82] |

Early TNBC Surgery |

Bevacizumab + chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone |

IDFS 80% vs. 77% OS 88% vs. 88% |

|

CALGB 40603 Phase II NCT00861705 [83] |

TNBC Stage II to III |

Bevacizumab + chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone or Carboplatin + chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone |

pCR 59% vs. 48% (p = 0.0089) (Bevacizumab) pCR 60% vs. 44% (p = 0.0018) (Carboplatin) |

||

|

EGFR inhibitors |

Cetuximab |

TBCRC 001 Phase II NCT00232505 [84] |

TNBC MBC |

Cetuximab + carboplatin |

Response < 20% TTP 2.1 months |

|

Phase II NCT00463788 [85] |

TNBC MBC Prior chemotherapy treatment |

Cetuximab + cisplatin vs. cisplatin alone |

ORR 20% vs. 10% (p = 0.11) PFS 3.7 months vs. 1.7 months (HR 0.67; p = 0.032) OS 12.9 months vs. 9.4 months (HR 0.82; p = 0.31) |

||

|

mTORC1 inhibitors |

Everolimus |

Phase II NCT00930930 [86] |

TNBC Stage II or III Neoadjuvant treatment |

Everolimus + cisplatin and paclitaxel vs. placebo + cisplatin and paclitaxel |

pCR 36% vs. 49% |

|

Akt inhibitors |

Ipatasertib |

LOTUS Phase II NCT02162719 [87] |

TNBC Locally advanced or MBC No prior sytemic therapy |

Ipatasertib + paclitaxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel |

PFS 6.2 months vs. 4.9 months (HR 0.60; p = 0.037) PFS 6.2 months vs. 3.7 moths (HR 0.58; p = 0.18) in PTEN-low patients |

|

FAIRLANE Phase II NCT02301988 [88] |

Early TNBC Neoadjuvant treatment |

Ipatasertib + paclitaxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel |

pCR 17% vs. 13% pCR 16% vs. 13% PTEN-low patients pCR 18% vs. 12% PIK3CA/AKT1/PTEN-altered patients |

||

|

Capivasertib |

PAKT Phase II NCT02423603 [89] |

TNBC MBC No prior chemotherapy treatment |

Capivasertib + paclitaxel vs. placebo + paclitaxel |

PFS 5.9 months vs. 12.6 months (HR 0.61; p = 0.04) |

|

|

Androgen receptor inhibitors |

Bicalutamide |

Phase II NCT00468715 [90] |

HR- AR+ or AR- MBC |

Bicalutamide monotherapy |

CBR 19% PFS 12 weeks |

|

Enzalutamide |

Phase II NCT01889238 [91] |

TNBC AR+ Locally advanced or MBC |

Enzalutamide monotherapy |

CBR 25% OS 12.7 months |

|

|

CYP17 inhibitors |

Abiraterone acetate |

UCBG 12-1 Phase II NCT01842321 [92] |

TNBC AR+ Locally advanced or MBC Centrally reviewed Prior chemotherapy |

Abiraterone acetate + prednisone |

CBR 20% ORR 6.7% PFS 2.8 months |

|

Anti-PDL1 antibodies |

Atezolizumab |

Impassion 130 Phase III NCT02425891 [93] |

TNBC Locally advanced or MBC No prior treatment |

Atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel vs. placebo + nab-paclitaxel |

OS 21.0 months vs. 18.7 months (HR 0.86; p = 0.078) OS 25.0 months vs. 18.0 months (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.94)) in PDL-1+ patients |

|

Impassion 031 Phase III NCT03197935 [94] |

TNBC Stage II to III No prior treatment |

Atezolizumab + chemotherapy vs. placebo + chemotherapy |

pCR 95% vs. 69% p = 0.0044 |

||

|

Durvalumab |

GeparNuevo Phase II NCT02685059 [95] |

TNBC MBC Stromal tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (sTILs) |

Durvalumab vs. placebo |

pCR 53.4% vs. 44.2% pCR 61.0% vs. 41.4% in window cohort |

|

|

SAFIRO BREAST-IMMUNO Phase II NCT02299999 [96] |

HER2- MBC Prior chemotherapy |

Durvalumab vs. maintenance chemotherapy |

HR of death 0.37 for PDL-1+ patients HR of death 0.49 for PDL-1- patients |

||

|

Phase I NCT02484404 [97] |

Recurrent women’s cancers including TNBC |

Durvalumab + cediranib + olaparib |

Partial response 44% CBR 67% |

||

|

Avelumab |

JAVELIN Phase Ib NCT01772004 [98] |

MBC Prior standard-of-care therapy |

Avelumab monotherapy |

ORR 3.0% overall ORR 5.2% in TNBC ORR 16.7% in PDL-1+ vs. 1.6% in PDL-1- overall ORR 22.2.% in PDL-1+ vs. 2.6% in PDL-1- in TNBC |

|

|

Anti-PD1 antibodies |

Pembrolizumab |

KEYNOTE-086 Phase II NCT02447003 [99] |

TNBC MBC Prior or no prior systemic therapy |

Pembrolizumab monotherapy |

Previously treated patients: ORR 5.3% overall ORR 5.7% PDL-1+ patients PFS 2.0 months OS 9.0 months Non-previously pretreated: ORR 21.4% PFS 2.1 months OS 18.0 months |

|

KEYNOTE-119 Phase III NCT02555657 [100] |

TNBC MBC Prior systemic therapy |

Pembrolizumab vs. chemotherapy |

OS 12.7 months vs. 11.6 months (HR 0.78; p = 0.057) in PDL1+ patients OS 9.9 months vs. 10.8 months (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.81–1.15) |

||

|

KEYNOTE-355 Phase III NCT02819518 [101] |

TNBC MBC No prior systemic therapy |

Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy vs. placebo + chemotherapy |

PFS 9.7 months vs. 5.6 months (HR 0.65; p = 0.0012) in PDL-1+ patients PFS 7.6 months vs. 5.6 months (HR 0.74; p = 0.0014) |

||

|

KEYNOTE-522 Phase III NCT03036488 [102] |

Early TNBC Stage II to III No prior treatment |

Pembrolizumab + paclitaxel and carboplatin vs. placebo + paclitaxel and carboplatin |

pCR 64.8% vs. 51.2 % (p < 0.001) |

||

|

Anti-CDL4 antibodies |

Tremelimumab |

Phase I [103] |

Incurable MBC |

Tremelimumab + radiotherapy |

OS 50.8 months |

|

Vaccines |

PPV |

Phase II UMIN000001844 [104] |

TNBC MBC Prior systemic therapy |

PPV vaccine |

PFS 7.5 months OS 11.1 months |

|

STn-KLH |

Phase III NCT00003638 [105] |

MBC Prior chemotherapy Partial or complete response |

STn-KLH vaccine vs. non-vaccine |

TTP 3.4 months vs. 3.0 months |

TNBC: triple negative breast cancer; HER2: human epidermal growth factor receptor; HR: hormonal receptor; MBC: metastatic breast cancer; BC: breast cancer; AR: androgen receptor; PPV: personalized peptide vaccine; PFS: progression free survival; CBR: clinical benefit rate; ORR: objective response rate; IDFS: invasive disease-free survival; OS: overall survival; TTP: time to progression; pCR: pathologic complete response; HR: hazard ratio.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jpm11080808

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30.

- Joshi, H.; Press, M.F. Molecular Oncology of Breast Cancer. In The Breast; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 282–307.e5. ISBN 978-0-323-35955-9. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780323359559000222 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Gao, J.J.; Swain, S.M. Luminal A Breast Cancer and Molecular Assays: A Review. Oncologist 2018, 23, 556–565.

- Ades, F.; Zardavas, D.; Bozovic-Spasojevic, I.; Pugliano, L.; Fumagalli, D.; de Azambuja, E.; Viale, G.; Sotiriou, C.; Piccart, M. Luminal B breast cancer: Molecular characterization, clinical management, and future perspectives. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2794–2803.

- Loibl, S.; Gianni, L. HER2-positive breast cancer. Lancet 2017, 389, 2415–2429.

- Bergin, A.R.T.; Loi, S. Triple-negative breast cancer: Recent treatment advances. F1000Research 2019, 8.

- Al-thoubaity, F.K. Molecular classification of breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2020, 49, 44–48.

- Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Palacios, J.; Cano, A.; Moreno-Bueno, G. “New” molecular taxonomy in breast cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2008, 10, 777–785.

- Engstrøm, M.J.; Opdahl, S.; Hagen, A.I.; Romundstad, P.R.; Akslen, L.A.; Haugen, O.A.; Vatten, L.J.; Bofin, A.M. Molecular subtypes, histopathological grade and survival in a historic cohort of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 140, 463–473.

- Hennigs, A.; Riedel, F.; Gondos, A.; Sinn, P.; Schirmacher, P.; Marmé, F.; Jäger, D.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Stieber, A.; Lindel, K.; et al. Prognosis of breast cancer molecular subtypes in routine clinical care: A large prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 734.

- Fragomeni, S.M.; Sciallis, A.; Jeruss, J.S. Molecular Subtypes and Local-Regional Control of Breast Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 95–120.

- Female Breast Cancer Subtypes—Cancer Stat Facts. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Elston, E.W.; Ellis, I.O. Method for grading breast cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 1993, 46, 189–190.

- Amin, M.B.; Greene, F.L.; Edge, S.B.; Compton, C.C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Brookland, R.K.; Meyer, L.; Gress, D.M.; Byrd, D.R.; Winchester, D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging: The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 93–99.

- Harbeck, N.; Penault-Llorca, F.; Cortes, J.; Gnant, M.; Houssami, N.; Poortmans, P.; Ruddy, K.; Tsang, J.; Cardoso, F. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 66.

- Pisani, P.; Bray, F.; Parkin, D.M. Estimates of the world-wide prevalence of cancer for 25 sites in the adult population. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 97, 72–81.

- Nofech-Mozes, S.; Trudeau, M.; Kahn, H.K.; Dent, R.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A.; Hanna, W.M. Patterns of recurrence in the basal and non-basal subtypes of triple-negative breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 118, 131–137.

- Schnitt, S.J.; Moran, M.S.; Giuliano, A.E. Lumpectomy Margins for Invasive Breast Cancer and Ductal Carcinoma in Situ: Current Guideline Recommendations, Their Implications, and Impact. JCO 2020, 38, 2240–2245.

- Fisher, B.; Anderson, S.; Bryant, J.; Margolese, R.G.; Deutsch, M.; Fisher, E.R.; Jeong, J.-H.; Wolmark, N. Twenty-Year Follow-up of a Randomized Trial Comparing Total Mastectomy, Lumpectomy, and Lumpectomy plus Irradiation for the Treatment of Invasive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1233–1241.

- Grubbé, E.H. Priority in the Therapeutic Use of X-rays. Radiology 1933, 21, 156–162.

- Boyages, J. Radiation therapy and early breast cancer: Current controversies. Med. J. Aust. 2017, 207, 216–222.

- EBCTCG (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group). Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: Meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 2127–2135.

- Bartelink, H.; Maingon, P.; Poortmans, P.; Weltens, C.; Fourquet, A.; Jager, J.; Schinagl, D.; Oei, B.; Rodenhuis, C.; Horiot, J.-C.; et al. Whole-breast irradiation with or without a boost for patients treated with breast-conserving surgery for early breast cancer: 20-year follow-up of a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 47–56.

- He, M.Y.; Rancoule, C.; Rehailia-Blanchard, A.; Espenel, S.; Trone, J.-C.; Bernichon, E.; Guillaume, E.; Vallard, A.; Magné, N. Radiotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: Current situation and upcoming strategies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 131, 96–101.

- Nabholtz, J.-M.; Gligorov, J. The role of taxanes in the treatment of breast cancer. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005, 6, 1073–1094.

- Penel, N.; Adenis, A.; Bocci, G. Cyclophosphamide-based metronomic chemotherapy: After 10 years of experience, where do we stand and where are we going? Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2012, 82, 40–50.

- Gewirtz, D. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999, 57, 727–741.

- Moos, P.J.; Fitzpatrick, F.A. Taxanes propagate apoptosis via two cell populations with distinctive cytological and molecular traits. Cell Growth Differ. 1998, 9, 687–697.

- Howlader, N.; Altekruse, S.F.; Li, C.I.; Chen, V.W.; Clarke, C.A.; Ries, L.A.G.; Cronin, K.A. US Incidence of Breast Cancer Subtypes Defined by Joint Hormone Receptor and HER2 Status. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106.

- El Sayed, R.; El Jamal, L.; El Iskandarani, S.; Kort, J.; Abdel Salam, M.; Assi, H. Endocrine and Targeted Therapy for Hormone-Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: Insights to Sequencing Treatment and Overcoming Resistance Based on Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 510.

- Slamon, D.; Clark, G.; Wong, S.; Levin, W.; Ullrich, A.; McGuire, W. Human breast cancer: Correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science 1987, 235, 177–182.

- Press, M.F.; Pike, M.C.; Chazin, V.R.; Hung, G.; Udove, J.A.; Markowicz, M.; Danyluk, J.; Godolphin, W.; Sliwkowski, M.; Akita, R. Her-2/neu expression in node-negative breast cancer: Direct tissue quantitation by computerized image analysis and association of overexpression with increased risk of recurrent disease. Cancer Res. 1993, 53, 4960–4970.

- Goutsouliak, K.; Veeraraghavan, J.; Sethunath, V.; De Angelis, C.; Osborne, C.K.; Rimawi, M.F.; Schiff, R. Towards personalized treatment for early stage HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 233–250.

- Chen, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Cao, S.; Li, X. Association Between BRCA Status and Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 909.

- Li, M.; Yu, X. Function of BRCA1 in the DNA Damage Response Is Mediated by ADP-Ribosylation. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 693–704.

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; Phillips, K.-A.; Mooij, T.M.; Roos-Blom, M.-J.; Jervis, S.; van Leeuwen, F.E.; Milne, R.L.; Andrieu, N.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA 2017, 317, 2402–2416.

- Golia, B.; Singh, H.R.; Timinszky, G. Poly-ADP-ribosylation signaling during DNA damage repair. Front. Biosci. 2015, 20, 440–457.

- Farmer, H.; McCabe, N.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.N.J.; Johnson, D.A.; Richardson, T.B.; Santarosa, M.; Dillon, K.J.; Hickson, I.; Knights, C.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921.

- Zimmer, A.S.; Gillard, M.; Lipkowitz, S.; Lee, J.-M. Update on PARP Inhibitors in Breast Cancer. Curr. Treat. Options Oncol. 2018, 19, 21.

- Brufsky, A.M.; Dickler, M.N. Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Exploiting Signaling Pathways Implicated in Endocrine Resistance. Oncologist 2018, 23, 528–539.

- Baselga, J.; Im, S.-A.; Iwata, H.; Cortés, J.; De Laurentiis, M.; Jiang, Z.; Arteaga, C.L.; Jonat, W.; Clemons, M.; Ito, Y.; et al. Buparlisib plus fulvestrant versus placebo plus fulvestrant in postmenopausal, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (BELLE-2): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 904–916.

- Di Leo, A.; Johnston, S.; Lee, K.S.; Ciruelos, E.; Lønning, P.E.; Janni, W.; O’Regan, R.; Mouret-Reynier, M.-A.; Kalev, D.; Egle, D.; et al. Buparlisib plus fulvestrant in postmenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer progressing on or after mTOR inhibition (BELLE-3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 87–100.

- Martín, M.; Chan, A.; Dirix, L.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Hegg, R.; Manikhas, A.; Shtivelband, M.; Krivorotko, P.; Batista López, N.; Campone, M.; et al. A randomized adaptive phase II/III study of buparlisib, a pan-class I PI3K inhibitor, combined with paclitaxel for the treatment of HER2- advanced breast cancer (BELLE-4). Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 313–320.

- Krop, I.E.; Mayer, I.A.; Ganju, V.; Dickler, M.; Johnston, S.; Morales, S.; Yardley, D.A.; Melichar, B.; Forero-Torres, A.; Lee, S.C.; et al. Pictilisib for oestrogen receptor-positive, aromatase inhibitor-resistant, advanced or metastatic breast cancer (FERGI): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 811–821.

- Vuylsteke, P.; Huizing, M.; Petrakova, K.; Roylance, R.; Laing, R.; Chan, S.; Abell, F.; Gendreau, S.; Rooney, I.; Apt, D.; et al. Pictilisib PI3Kinase inhibitor (a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K] inhibitor) plus paclitaxel for the treatment of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, locally recurrent, or metastatic breast cancer: Interim analysis of the multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase II randomised PEGGY study. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 2059–2066.

- Mayer, I.A.; Abramson, V.G.; Formisano, L.; Balko, J.M.; Estrada, M.V.; Sanders, M.E.; Juric, D.; Solit, D.; Berger, M.F.; Won, H.H.; et al. A Phase Ib Study of Alpelisib (BYL719), a PI3Kα-Specific Inhibitor, with Letrozole in ER+/HER2- Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 26–34.

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I.A.; Kaufman, B.; et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA -Mutated, Hormone Receptor–Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940.

- Mayer, I.A.; Prat, A.; Egle, D.; Blau, S.; Fidalgo, J.A.P.; Gnant, M.; Fasching, P.A.; Colleoni, M.; Wolff, A.C.; Winer, E.P.; et al. A Phase II Randomized Study of Neoadjuvant Letrozole Plus Alpelisib for Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Breast Cancer (NEO-ORB). Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2975–2987.

- Baselga, J.; Dent, S.F.; Cortés, J.; Im, Y.-H.; Diéras, V.; Harbeck, N.; Krop, I.E.; Verma, S.; Wilson, T.R.; Jin, H.; et al. Phase III study of taselisib (GDC-0032) + fulvestrant (FULV) v FULV in patients (pts) with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, PIK3CA-mutant (MUT), locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (MBC): Primary analysis from SANDPIPER. JCO 2018, 36, LBA1006.

- Saura, C.; Hlauschek, D.; Oliveira, M.; Zardavas, D.; Jallitsch-Halper, A.; de la Peña, L.; Nuciforo, P.; Ballestrero, A.; Dubsky, P.; Lombard, J.M.; et al. Neoadjuvant letrozole plus taselisib versus letrozole plus placebo in postmenopausal women with oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, early-stage breast cancer (LORELEI): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1226–1238.

- Baselga, J.; Campone, M.; Piccart, M.; Burris, H.A.; Rugo, H.S.; Sahmoud, T.; Noguchi, S.; Gnant, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Lebrun, F.; et al. Everolimus in postmenopausal hormone-receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 520–529.

- Bachelot, T.; Bourgier, C.; Cropet, C.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Ferrero, J.-M.; Freyer, G.; Abadie-Lacourtoisie, S.; Eymard, J.-C.; Debled, M.; Spaëth, D.; et al. Randomized phase II trial of everolimus in combination with tamoxifen in patients with hormone receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer with prior exposure to aromatase inhibitors: A GINECO study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2718–2724.

- Kornblum, N.; Zhao, F.; Manola, J.; Klein, P.; Ramaswamy, B.; Brufsky, A.; Stella, P.J.; Burnette, B.; Telli, M.; Makower, D.F.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Fulvestrant Plus Everolimus or Placebo in Postmenopausal Women With Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer Resistant to Aromatase Inhibitor Therapy: Results of PrE0102. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1556–1563.

- Jones, R.H.; Casbard, A.; Carucci, M.; Cox, C.; Butler, R.; Alchami, F.; Madden, T.-A.; Bale, C.; Bezecny, P.; Joffe, J.; et al. Fulvestrant plus capivasertib versus placebo after relapse or progression on an aromatase inhibitor in metastatic, oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (FAKTION): A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 345–357.

- Smyth, L.M.; Tamura, K.; Oliveira, M.; Ciruelos, E.M.; Mayer, I.A.; Sablin, M.-P.; Biganzoli, L.; Ambrose, H.J.; Ashton, J.; Barnicle, A.; et al. Capivasertib, an AKT Kinase Inhibitor, as Monotherapy or in Combination with Fulvestrant in Patients with AKT1E17K-Mutant, ER-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 3947–3957.

- Finn, R.S.; Crown, J.P.; Lang, I.; Boer, K.; Bondarenko, I.M.; Kulyk, S.O.; Ettl, J.; Patel, R.; Pinter, T.; Schmidt, M.; et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): A randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 25–35.

- Finn, R.S.; Martin, M.; Rugo, H.S.; Jones, S.; Im, S.-A.; Gelmon, K.; Harbeck, N.; Lipatov, O.N.; Walshe, J.M.; Moulder, S.; et al. Palbociclib and Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1925–1936.

- Cristofanilli, M.; Turner, N.C.; Bondarenko, I.; Ro, J.; Im, S.-A.; Masuda, N.; Colleoni, M.; DeMichele, A.; Loi, S.; Verma, S.; et al. Fulvestrant plus palbociclib versus fulvestrant plus placebo for treatment of hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer that progressed on previous endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3): Final analysis of the multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 425–439.

- Hortobagyi, G.N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Burris, H.A.; Yap, Y.S.; Sonke, G.S.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Campone, M.; Petrakova, K.; Blackwell, K.L.; Winer, E.P.; et al. Updated results from MONALEESA-2, a phase III trial of first-line ribociclib plus letrozole versus placebo plus letrozole in hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1541–1547.

- Slamon, D.J.; Neven, P.; Chia, S.; Fasching, P.A.; De Laurentiis, M.; Im, S.-A.; Petrakova, K.; Bianchi, G.V.; Esteva, F.J.; Martín, M.; et al. Phase III Randomized Study of Ribociclib and Fulvestrant in Hormone Receptor-Positive, Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative Advanced Breast Cancer: MONALEESA-3. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2465–2472.

- Sledge, G.W.; Toi, M.; Neven, P.; Sohn, J.; Inoue, K.; Pivot, X.; Burdaeva, O.; Okera, M.; Masuda, N.; Kaufman, P.A.; et al. MONARCH 2: Abemaciclib in Combination With Fulvestrant in Women With HR+/HER2- Advanced Breast Cancer Who Had Progressed While Receiving Endocrine Therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2875–2884.

- Goetz, M.P.; Toi, M.; Campone, M.; Sohn, J.; Paluch-Shimon, S.; Huober, J.; Park, I.H.; Trédan, O.; Chen, S.-C.; Manso, L.; et al. MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib As Initial Therapy for Advanced Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3638–3646.

- Escrivá-de-Romaní, S.; Arumí, M.; Bellet, M.; Saura, C. HER2-positive breast cancer: Current and new therapeutic strategies. Breast 2018, 39, 80–88.

- Modi, S.; Saura, C.; Yamashita, T.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Tamura, K.; Andre, F.; Iwata, H.; Ito, Y.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 610–621.

- Saura, C.; Thistlethwaite, F.; Banerji, U.; Lord, S.; Moreno, V.; MacPherson, I.; Boni, V.; Rolfo, C.D.; de Vries, E.G.E.; Van Herpen, C.M.L.; et al. A phase I expansion cohorts study of SYD985 in heavily pretreated patients with HER2-positive or HER2-low metastatic breast cancer. JCO 2018, 36, 1014.

- Bang, Y.J.; Giaccone, G.; Im, S.A.; Oh, D.Y.; Bauer, T.M.; Nordstrom, J.L.; Li, H.; Chichili, G.R.; Moore, P.A.; Hong, S.; et al. First-in-human phase 1 study of margetuximab (MGAH22), an Fc-modified chimeric monoclonal antibody, in patients with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 855–861.

- Murthy, R.K.; Loi, S.; Okines, A.; Paplomata, E.; Hamilton, E.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Lin, N.U.; Borges, V.; Abramson, V.; Anders, C.; et al. Tucatinib, Trastuzumab, and Capecitabine for HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 597–609.

- Park, Y.H.; Lee, K.-H.; Sohn, J.H.; Lee, K.S.; Jung, K.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, K.H.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, G.M.; et al. A phase II trial of the pan-HER inhibitor poziotinib, in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who had received at least two prior HER2-directed regimens: Results of the NOV120101-203 trial. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 3240–3247.

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Clifton, G.T.; Holmes, J.P.; Schneble, E.; van Echo, D.; Ponniah, S.; Peoples, G.E. Final report of the phase I/II clinical trial of the E75 (nelipepimut-S) vaccine with booster inoculations to prevent disease recurrence in high-risk breast cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1735–1742.

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Ardavanis, A.; Litton, J.K.; Shumway, N.M.; Hale, D.F.; Murray, J.L.; Perez, S.A.; Ponniah, S.; Baxevanis, C.N.; Papamichail, M.; et al. Primary analysis of a prospective, randomized, single-blinded phase II trial evaluating the HER2 peptide GP2 vaccine in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 66192–66201.

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Ardavanis, A.; Symanowski, J.; Murray, J.L.; Shumway, N.M.; Litton, J.K.; Hale, D.F.; Perez, S.A.; Anastasopoulou, E.A.; Pistamaltzian, N.F.; et al. Primary analysis of a prospective, randomized, single-blinded phase II trial evaluating the HER2 peptide AE37 vaccine in breast cancer patients to prevent recurrence. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1241–1248.

- Jhaveri, K.; Drago, J.Z.; Shah, P.D.; Wang, R.; Pareja, F.; Ratzon, F.; Iasonos, A.; Patil, S.; Rosen, N.; Fornier, M.N.; et al. A Phase I study of alpelisib in combination with trastuzumab and LJM716 in patients with PIK3CA-mutated HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021.

- Jain, S.; Shah, A.N.; Santa-Maria, C.A.; Siziopikou, K.; Rademaker, A.; Helenowski, I.; Cristofanilli, M.; Gradishar, W.J. Phase I study of alpelisib (BYL-719) and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (MBC) after trastuzumab and taxane therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 171, 371–381.

- Keegan, N.M.; Furney, S.J.; Walshe, J.M.; Gullo, G.; Kennedy, M.J.; Smith, D.; McCaffrey, J.; Kelly, C.M.; Egan, K.; Kerr, J.; et al. Phase Ib Trial of Copanlisib, A Phosphoinositide-3 Kinase (PI3K) Inhibitor, with Trastuzumab in Advanced Pre-Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer “PantHER”. Cancers 2021, 13, 1225.

- Hurvitz, S.A.; Andre, F.; Jiang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Mano, M.S.; Neciosup, S.P.; Tseng, L.-M.; Zhang, Q.; Shen, K.; Liu, D.; et al. Combination of everolimus with trastuzumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-1): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 816–829.

- André, F.; O’Regan, R.; Ozguroglu, M.; Toi, M.; Xu, B.; Jerusalem, G.; Masuda, N.; Wilks, S.; Arena, F.; Isaacs, C.; et al. Everolimus for women with trastuzumab-resistant, HER2-positive, advanced breast cancer (BOLERO-3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 580–591.

- Ciruelos, E.; Villagrasa, P.; Pascual, T.; Oliveira, M.; Pernas, S.; Paré, L.; Escrivá-de-Romaní, S.; Manso, L.; Adamo, B.; Martínez, E.; et al. Palbociclib and Trastuzumab in HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer: Results from the Phase II SOLTI-1303 PATRICIA Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 5820–5829.

- Goel, S.; Pernas, S.; Tan-Wasielewski, Z.; Barry, W.T.; Bardia, A.; Rees, R.; Andrews, C.; Tahara, R.K.; Trippa, L.; Mayer, E.L.; et al. Ribociclib Plus Trastuzumab in Advanced HER2-Positive Breast Cancer: Results of a Phase 1b/2 Trial. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, 399–404.

- Tolaney, S.M.; Wardley, A.M.; Zambelli, S.; Hilton, J.F.; Troso-Sandoval, T.A.; Ricci, F.; Im, S.-A.; Kim, S.-B.; Johnston, S.R.; Chan, A.; et al. Abemaciclib plus trastuzumab with or without fulvestrant versus trastuzumab plus standard-of-care chemotherapy in women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive advanced breast cancer (monarcHER): A randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 763–775.

- Bianchini, G.; Balko, J.M.; Mayer, I.A.; Sanders, M.E.; Gianni, L. Triple-negative breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 674–690.

- Bardia, A.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Tolaney, S.M.; Loirat, D.; Punie, K.; Oliveira, M.; Brufsky, A.; Sardesai, S.D.; Kalinsky, K.; Zelnak, A.B.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1529–1541.

- Bell, R.; Brown, J.; Parmar, M.; Toi, M.; Suter, T.; Steger, G.G.; Pivot, X.; Mackey, J.; Jackisch, C.; Dent, R.; et al. Final efficacy and updated safety results of the randomized phase III BEATRICE trial evaluating adjuvant bevacizumab-containing therapy in triple-negative early breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 754–760.

- Sikov, W.M.; Berry, D.A.; Perou, C.M.; Singh, B.; Cirrincione, C.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Kuzma, C.S.; Pluard, T.J.; Somlo, G.; Port, E.R.; et al. Impact of the addition of carboplatin and/or bevacizumab to neoadjuvant once-per-week paclitaxel followed by dose-dense doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide on pathologic complete response rates in stage II to III triple-negative breast cancer: CALGB 40603 (Alliance). J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 13–21.

- Carey, L.A.; Rugo, H.S.; Marcom, P.K.; Mayer, E.L.; Esteva, F.J.; Ma, C.X.; Liu, M.C.; Storniolo, A.M.; Rimawi, M.F.; Forero-Torres, A.; et al. TBCRC 001: Randomized Phase II Study of Cetuximab in Combination With Carboplatin in Stage IV Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCO 2012, 30, 2615–2623.

- Baselga, J.; Gómez, P.; Greil, R.; Braga, S.; Climent, M.A.; Wardley, A.M.; Kaufman, B.; Stemmer, S.M.; Pêgo, A.; Chan, A.; et al. Randomized Phase II Study of the Anti–Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Monoclonal Antibody Cetuximab With Cisplatin Versus Cisplatin Alone in Patients With Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. JCO 2013, 31, 2586–2592.

- Jovanović, B.; Mayer, I.A.; Mayer, E.L.; Abramson, V.G.; Bardia, A.; Sanders, M.E.; Kuba, M.G.; Estrada, M.V.; Beeler, J.S.; Shaver, T.M.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Neoadjuvant Study of Cisplatin, Paclitaxel With or Without Everolimus in Patients with Stage II/III Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC): Responses and Long-term Outcome Correlated with Increased Frequency of DNA Damage Response Gene Mutations, TNBC Subtype, AR Status, and Ki67. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4035–4045.

- Kim, S.-B.; Dent, R.; Im, S.-A.; Espié, M.; Blau, S.; Tan, A.R.; Isakoff, S.J.; Oliveira, M.; Saura, C.; Wongchenko, M.J.; et al. Ipatasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (LOTUS): A multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1360–1372.

- Oliveira, M.; Saura, C.; Nuciforo, P.; Calvo, I.; Andersen, J.; Passos-Coelho, J.L.; Gil Gil, M.; Bermejo, B.; Patt, D.A.; Ciruelos, E.; et al. FAIRLANE, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized phase II trial of neoadjuvant ipatasertib plus paclitaxel for early triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1289–1297.

- Schmid, P.; Abraham, J.; Chan, S.; Wheatley, D.; Brunt, A.M.; Nemsadze, G.; Baird, R.D.; Park, Y.H.; Hall, P.S.; Perren, T.; et al. Capivasertib Plus Paclitaxel Versus Placebo Plus Paclitaxel As First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: The PAKT Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 423–433.

- Gucalp, A.; Tolaney, S.; Isakoff, S.J.; Ingle, J.N.; Liu, M.C.; Carey, L.A.; Blackwell, K.; Rugo, H.; Nabell, L.; Forero, A.; et al. Phase II Trial of Bicalutamide in Patients with Androgen Receptor–Positive, Estrogen Receptor–Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5505–5512.

- Traina, T.A.; Miller, K.; Yardley, D.A.; Eakle, J.; Schwartzberg, L.S.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Gradishar, W.; Schmid, P.; Winer, E.; Kelly, C.; et al. Enzalutamide for the Treatment of Androgen Receptor-Expressing Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 884–890.

- Bonnefoi, H.; Grellety, T.; Tredan, O.; Saghatchian, M.; Dalenc, F.; Mailliez, A.; L’Haridon, T.; Cottu, P.; Abadie-Lacourtoisie, S.; You, B.; et al. A phase II trial of abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with triple-negative androgen receptor positive locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (UCBG 12-1). Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 812–818.

- Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.S.; Adams, S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Henschel, V.; Molinero, L.; Chui, S.Y.; et al. Atezolizumab plus nab-paclitaxel as first-line treatment for unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion130): Updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 44–59.

- Mittendorf, E.A.; Zhang, H.; Barrios, C.H.; Saji, S.; Jung, K.H.; Hegg, R.; Koehler, A.; Sohn, J.; Iwata, H.; Telli, M.L.; et al. Neoadjuvant atezolizumab in combination with sequential nab-paclitaxel and anthracycline-based chemotherapy versus placebo and chemotherapy in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (IMpassion031): A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1090–1100.

- Loibl, S.; Untch, M.; Burchardi, N.; Huober, J.; Sinn, B.V.; Blohmer, J.-U.; Grischke, E.-M.; Furlanetto, J.; Tesch, H.; Hanusch, C.; et al. A randomised phase II study investigating durvalumab in addition to an anthracycline taxane-based neoadjuvant therapy in early triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical results and biomarker analysis of GeparNuevo study. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1279–1288.

- Bachelot, T.; Filleron, T.; Bieche, I.; Arnedos, M.; Campone, M.; Dalenc, F.; Coussy, F.; Sablin, M.-P.; Debled, M.; Lefeuvre-Plesse, C.; et al. Durvalumab compared to maintenance chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: The randomized phase II SAFIR02-BREAST IMMUNO trial. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 250–255.

- Zimmer, A.S.; Nichols, E.; Cimino-Mathews, A.; Peer, C.; Cao, L.; Lee, M.-J.; Kohn, E.C.; Annunziata, C.M.; Lipkowitz, S.; Trepel, J.B.; et al. A phase I study of the PD-L1 inhibitor, durvalumab, in combination with a PARP inhibitor, olaparib, and a VEGFR1-3 inhibitor, cediranib, in recurrent women’s cancers with biomarker analyses. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 197.

- Dirix, L.Y.; Takacs, I.; Jerusalem, G.; Nikolinakos, P.; Arkenau, H.-T.; Forero-Torres, A.; Boccia, R.; Lippman, M.E.; Somer, R.; Smakal, M.; et al. Avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer: A phase 1b JAVELIN Solid Tumor study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 167, 671–686.

- Adams, S.; Schmid, P.; Rugo, H.S.; Winer, E.P.; Loirat, D.; Awada, A.; Cescon, D.W.; Iwata, H.; Campone, M.; Nanda, R.; et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously treated metastatic triple-negative breast cancer: Cohort A of the phase II KEYNOTE-086 study. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 397–404.

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1817–1828.

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Pusztai, L.; McArthur, H.; Kümmel, S.; Bergh, J.; Denkert, C.; Park, Y.H.; Hui, R.; Harbeck, N.; et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 810–821.

- Jiang, D.M.; Fyles, A.; Nguyen, L.T.; Neel, B.G.; Sacher, A.; Rottapel, R.; Wang, B.X.; Ohashi, P.S.; Sridhar, S.S. Phase I study of local radiation and tremelimumab in patients with inoperable locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 2947–2958.

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Clinical Features and Patterns of Recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4434.

- Takahashi, R.; Toh, U.; Iwakuma, N.; Takenaka, M.; Otsuka, H.; Furukawa, M.; Fujii, T.; Seki, N.; Kawahara, A.; Kage, M.; et al. Feasibility study of personalized peptide vaccination for metastatic recurrent triple-negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, R70.

- Miles, D.; Roché, H.; Martin, M.; Perren, T.J.; Cameron, D.A.; Glaspy, J.; Dodwell, D.; Parker, J.; Mayordomo, J.; Tres, A.; et al. Phase III multicenter clinical trial of the sialyl-TN (STn)-keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) vaccine for metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist 2011, 16, 1092–1100.