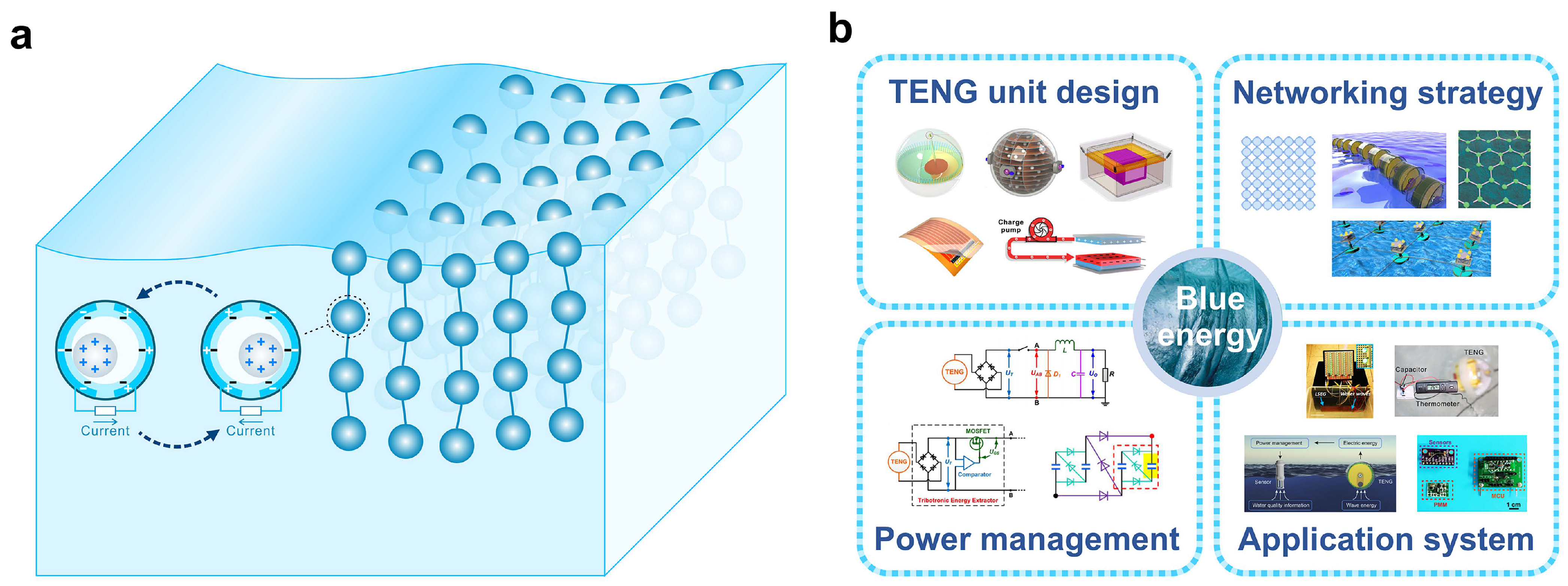

First proposed by Wang in 2012, the triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG, also called Wang generator) derived from Maxwell’s displacement current shows great prospect as a new technology to convert mechanical energy into electricity, based on the triboelectrification effect and electrostatic induction. TENGs present superiorities including light weight, cost-effectiveness, easy fabrication, and versatile material choices. The concept of harvesting blue energy using the TENG and its network was first brought out in 2014. As a new form of blue energy harvester, the TENG surpasses the EMG in that it intrinsically displays higher effectiveness under low frequency, owing to the unique feature of its output characteristics. Moreover, adopting the distributed architecture of light-weighted TENG networks can make it more suitable for collecting wave energy of high entropy compared with EMGs, which are oversized in volume and mass.

- triboelectric nanogenerator

- network

- blue energy

- wave energy

- energy harvesting

1. Introduction

Covering over 70% of the earth’s surface, ocean plays a crucial role for lives on the planet and can be regarded as an enormous source of blue energy, whose exploitation is greatly beneficial for dealing with energy challenges for human beings [1][2][3]. With extreme climate conditions taking place more frequently nowadays, the world feels the urge to take immediate action to alleviate climate deterioration caused by global warming [4][5][6]. Carbon neutrality is thus put forward as a goal to reach balance between emitting and absorbing carbon in the atmosphere [7]. One of the most effective methods is to develop and expand the use of clean energy that generates power without carbon emission, such as the enormous blue energy [8]. Meanwhile, with the increasing activities in ocean, equipment deployed in the far ocean is facing problems regarding an in situ and sustainable power supply, where blue energy is an ideal source for developing new power solutions for such applications, allowing self-powered marine systems and platforms, though the harvesting scale can be much smaller [9][10][11].

The ocean blue energy is typically in five forms: wave energy, tidal energy, current energy, thermal energy, and osmotic energy, among which the wave energy is promising for its wide distribution, easy accessibility, and large reserves. The wave energy around the coastline is estimated to be more than 2 TW (1 TW = 10 12 W) globally [12]. However, the present development of wave energy harvesting is challenged by its feature as a type of high-entropy energy, which refers to the chaotic, irregular waves with multiple amplitudes and constantly changing directions that are randomly distributed in the sea [13][14]. Most significantly, wave energy is typically distributed in a low-frequency regime, yet the most common and classic method of blue energy harvesting at status quo, the electromagnetic generator (EMG), performs rather poorly in low-frequency energy harvesting, which relies on propellers or other complex mechanical structures to drive bulky and heavy magnets and metal coils in order to transform mechanical energy into electricity [8]. Thus, it usually has high cost and low reliability.

2. TENG Systems for Blue Energy Harvesting

2.1. Fundamental Working Modes of TENGs

2.2. TENG Systems for Harvesting Blue Energy

3. Summary and Perspectives

| Device | Feature | Typical Output | Dimension Per Unit | Material | Mode | Year | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qsc | Isc | Power | Power Density | |||||||

| rolling-structured TENG [36] (RF-TENG) | rolling | 24 nC (wave, 1.43 Hz) |

1.2 µA (wave, 1.43 Hz) |

sphere diameter 6 cm | Nylon, Al, Kapton | freestanding | 2015 | low friction | ||

| ball-shell-structured TENG [37] (BS-TENG) | rolling | 72.6 nC (motor) |

1.8 μA (motor, 3 Hz) |

peak: 1.28 mW (motor, 5 Hz) average: 0.31 mW (motor, 5 Hz) |

peak: 7.13 W m−3 (motor, 5 Hz) average: 1.73 W m−3 (motor, 5 Hz) |

sphere diameter 7 cm | silicon rubber, POM, Ag-Cu | freestanding | 2018 | low damping force |

| 3D electrode TENG [23] | rolling, multilayer | 0.52 μC (motor) |

5 μA (motor, 2 Hz) |

peak: 8.75mW (motor, 1.67 Hz) average: 2.33 mW (motor, 1.67 Hz) |

peak: 32.6 W m−3 (motor, 1.67 Hz) average: 8.69 W m−3 (motor, 1.67 Hz) 2.05 W m−3 (wave) |

sphere diameter 8 cm | FEP, Cu | freestanding | 2019 | enhanced contact area |

| air-driven membrane structure TENG [24] | multilayer, mass-spring | 15 μC (rectified, motor) |

187 μA (motor) 1.77 A (contact switch) |

peak: 10 mW (motor) 313 W (contact switch) |

peak: 13.23 W m−3 (motor, core device) |

rectangular inner part: 12 cm × 9 cm | PTFE, soft membrane, Al, Cu | contact separation | 2017 | high output |

| spring-assisted spherical TENG [38] | multilayer, mass-spring | 0.67 µC | 120 µA | peak: 7.96 mW | peak: 15.2 W m−3 | sphere diameter 10 cm | Kapton, FEP, spring, Cu, Al | contact separation | 2018 | |

| nodding duck structure multi-track TENG [39] (NDM-FTENG) |

multilayer, rolling | ∼1.1 μA (two devices, wave) |

peak: 4 W m−3 (motor, 0.21 Hz) |

10 cm × 20 cm (width by height) | PPCF (PVDF/PDMS composite films), nylon, Cu, PET, PMMA | freestanding | 2021 | |||

| tandem disk TENG [27] (TD-TENG) | grating, pendulum, multilayer | 3.3 μC (wave, 0.58 Hz) |

peak: 45.0 mW (wave, 0.58 Hz) average: 7.5 mW (wave, 0.58 Hz) |

peak: 7.89 W m−3 (wave, 0.58 Hz) average: 1.3 W m−3 (wave, 0.58 Hz) 7.3 W m−3 (wave, 0.58 Hz, core device) |

volume 0.0057 m3 | PTFE, acrylic, Cu | freestanding | 2019 | high power density | |

| single pendulum inspired TENG (P-TENG) [22] |

pendulum, spacing | 18.2 nC (motor, 0.017 Hz) |

sphere diameter 13 cm | PTFE, Cu, acrylic, cotton thread | freestanding | 2019 | durable | |||

| robust swing-structured TENG [40] (SS TENG) |

pendulum, spacing | 256 nC (wave, 1.2 Hz) |

5.9 µA (wave, 1.2 Hz) |

peak: 4.56 mW (motor, 0.017 Hz) |

peak: 1.29 W m−3 (motor, 0.017 Hz) |

cylindrical shell: length 20 cm, outer diameter 15 cm | PTFE, Cu, acrylic | freestanding | 2020 | durable |

| active resonance TENG [41] (AR-TENG) |

pendulum, multilayer | 0.55 μC (wave) |

120 μA (wave) |

peak: 12.3 mW (wave) | peak: 16.31 W m−3 (wave, core device) |

volume 754 cm3 (core device) |

FEP, Kapton, Cu | contact separation | 2021 | omnidirectional |

| spiral TENG [42] | mass-spring | 15 μA (wave) |

peak: 2.76 W m−2 (motor, 30 Hz) |

sphere diameter 14 cm | Kapton, Cu, Al | contact separation | 2013 | |||

| liquid solid electrification enabled generator [32] (LSEG) | L-S contact | 75 nC (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

3 μA (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

average: 0.12 mW (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

average: 0.067 W m−2 (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

planar: 6 cm × 3 cm | water, FEP, Cu | freestanding | 2014 | |

| networked integrated TENG [43] (NI-TENG) | L-S contact | 13.5 μA (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

peak: 1.03 mW (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

peak: 0.147 W m−2 (motor, 0.5 m/s) |

planar: 10 cm × 7 cm | Kapton, PTFE, water | freestanding | 2018 | ||

| TENG based on charge shuttling [33] (CS-TENG) | charge pumping, multilayer | 53 μC (rectified, wave, 0.625 Hz) |

1.3 mA (wave, 0.625 Hz) |

peak: 126.67 mW (wave, 0.625 Hz) |

peak: 30.24 W m−3 (wave, 0.625 Hz) |

sphere diameter 20 cm | PTFE, PP, Cu, Zn-Al | contact separation | 2020 | high charge output |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nanoenergyadv1010003

References

- Isaacs, J.D.; Schmitt, W.R. Ocean Energy: Forms and Prospects. Science 1980, 207, 265.

- Salter, S.H. Wave power. Nature 1974, 249, 720–724.

- Ellabban, O.; Abu-Rub, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Renewable energy resources: Current status, future prospects and their enabling technology. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2014, 39, 748–764.

- Marshall, B.; Ezekiel, C.; Gichuki, J.; Mkumbo, O.; Sitoki, L.; Wanda, F. Global warming is reducing thermal stability and mitigating the effects of eutrophication in Lake Victoria (East Africa). Nat. Preced. 2009.

- Barbarossa, V.; Bosmans, J.; Wanders, N.; King, H.; Bierkens, M.F.P.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Schipper, A.M. Threats of global warming to the world’s freshwater fishes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1701.

- Yamaguchi, M.; Chan, J.C.L.; Moon, I.-J.; Yoshida, K.; Mizuta, R. Global warming changes tropical cyclone translation speed. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 47.

- van Soest, H.L.; den Elzen, M.G.J.; van Vuuren, D.P. Net-zero emission targets for major emitting countries consistent with the Paris Agreement. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2140.

- Tollefson, J. Power from the oceans: Blue energy. Nature 2014, 508, 302–304.

- Qin, Y.; Alam, A.U.; Pan, S.; Howlader, M.M.R.; Ghosh, R.; Hu, N.-X.; Jin, H.; Dong, S.; Chen, C.-H.; Deen, M.J. Integrated water quality monitoring system with pH, free chlorine, and temperature sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 255, 781–790.

- Callaway, E. Energy: To catch a wave. Nature 2007, 450, 156–159.

- Xi, F.; Pang, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.L. Self-powered intelligent buoy system by water wave energy for sustainable and autonomous wireless sensing and data transmission. Nano Energy 2019, 61, 1–9.

- Khaligh, A.; Onar, O.C. Energy Harvesting—Solar, Wind, and Ocean Energy Conversion Systems; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; Volume 89.

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303.

- Wang, Z.L. Entropy theory of distributed energy for internet of things. Nano Energy 2019, 58, 669–672.

- Niu, S.; Wang, Z.L. Theoretical systems of triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2015, 14, 161–192.

- Niu, S.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theoretical study of contact-mode triboelectric nanogenerators as an effective power source. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 3576–3583.

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theory of Sliding-Mode Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6184–6193.

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Lin, L.; Zhou, Y.S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theoretical Investigation and Structural Optimization of Single-Electrode Triboelectric Nanogenerators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 3332–3340.

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.S.; Lin, L.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Theory of freestanding triboelectric-layer-based nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2015, 12, 760–774.

- Wang, Z.L. Catch wave power in floating nets. Nature 2017, 542, 159–160.

- Wang, Z.L. From contact-electrification to triboelectric nanogenerators. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2021.

- Lin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Guo, H.; Wu, Z.; Zou, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Super-robust and frequency-multiplied triboelectric nanogenerator for efficient harvesting water and wind energy. Nano Energy 2019, 64, 103908.

- Yang, X.; Xu, L.; Lin, P.; Zhong, W.; Bai, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.L. Macroscopic self-assembly network of encapsulated high-performance triboelectric nanogenerators for water wave energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2019, 60, 404–412.

- Xu, L.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, T.; Chen, X.; Luo, J.; Tang, W.; Cao, X.; Wang, Z.L. Integrated triboelectric nanogenerator array based on air-driven membrane structures for water wave energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2017, 31, 351–358.

- Zhao, X.J.; Zhu, G.; Fan, Y.J.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Charging at the Nanostructured Solid/Liquid Interface for Area-Scalable Wave Energy Conversion and Its Use in Corrosion Protection. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 7671–7677.

- Xu, L.; Bu, T.Z.; Yang, X.D.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.L. Ultrahigh charge density realized by charge pumping at ambient conditions for triboelectric nanogenerators. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 625–633.

- Bai, Y.; Xu, L.; He, C.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Jiang, T.; Nie, J.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Z.L. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerators for self-powered, in-situ and real-time water quality mapping. Nano Energy 2019, 66, 104117.

- Kim, D.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kong, D.S.; Choi, M.; Kim, H.B.; Lee, J.-H.; Murillo, G.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.S.; Jung, J.H. Floating buoy-based triboelectric nanogenerator for an effective vibrational energy harvesting from irregular and random water waves in wild sea. Nano Energy 2018, 45, 247–254.

- Liu, G.; Xiao, L.; Chen, C.; Liu, W.; Pu, X.; Wu, Z.; Hu, C.; Wang, Z.L. Power cables for triboelectric nanogenerator networks for large-scale blue energy harvesting. Nano Energy 2020, 75, 104975.

- Xi, F.; Pang, Y.; Li, W.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, L.; Guo, T.; Liu, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.L. Universal power management strategy for triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2017, 37, 168–176.

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zeng, Q.; He, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Xi, Y.; Guo, H.; Hu, C.; et al. Switched-capacitor-convertors based on fractal design for output power management of triboelectric nanogenerator. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1883.

- Zhu, G.; Su, Y.; Bai, P.; Chen, J.; Jing, Q.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.L. Harvesting Water Wave Energy by Asymmetric Screening of Electrostatic Charges on a Nanostructured Hydrophobic Thin-Film Surface. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6031–6037.

- Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Pumping up the charge density of a triboelectric nanogenerator by charge-shuttling. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4203.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Tang, Q.; Xi, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Hu, C. Quantifying contact status and the air-breakdown model of charge-excitation triboelectric nanogenerators to maximize charge density. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1599.

- Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gong, S.; Wang, X. Sequential Infiltration Synthesis of Doped Polymer Films with Tunable Electrical Properties for Efficient Triboelectric Nanogenerator Development. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 4938–4944.

- Wang, X.; Niu, S.; Yin, Y.; Yi, F.; You, Z.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Based on Fully Enclosed Rolling Spherical Structure for Harvesting Low-Frequency Water Wave Energy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1501467.

- Xu, L.; Jiang, T.; Lin, P.; Shao, J.J.; He, C.; Zhong, W.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, Z.L. Coupled Triboelectric Nanogenerator Networks for Efficient Water Wave Energy Harvesting. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 1849–1858.

- Xiao, T.X.; Liang, X.; Jiang, T.; Xu, L.; Shao, J.J.; Nie, J.H.; Bai, Y.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Z.L. Spherical Triboelectric Nanogenerators Based on Spring-Assisted Multilayered Structure for Efficient Water Wave Energy Harvesting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1802634.

- Liu, L.; Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Hong, H.; Cui, H.; Duan, J.; Yang, Q.; Tang, Q. Nodding Duck Structure Multi-track Directional Freestanding Triboelectric Nanogenerator toward Low-Frequency Ocean Wave Energy Harvesting. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9412–9421.

- Jiang, T.; Pang, H.; An, J.; Lu, P.; Feng, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhong, W.; Wang, Z.L. Robust Swing-Structured Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Efficient Blue Energy Harvesting. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2000064.

- Zhang, C.; He, L.; Zhou, L.; Yang, O.; Yuan, W.; Wei, X.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.L. Active resonance triboelectric nanogenerator for harvesting omnidirectional water-wave energy. Joule 2021, 5, 1613–1623.

- Hu, Y.; Yang, J.; Jing, Q.; Niu, S.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.L. Triboelectric Nanogenerator Built on Suspended 3D Spiral Structure as Vibration and Positioning Sensor and Wave Energy Harvester. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 10424–10432.

- Zhao, X.J.; Kuang, S.Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhu, G. Highly Adaptive Solid–Liquid Interfacing Triboelectric Nanogenerator for Harvesting Diverse Water Wave Energy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 4280–4285.

- Xu, L.; Xu, L.; Luo, J.; Yan, Y.; Jia, B.-E.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.L. Hybrid All-in-One Power Source Based on High-Performance Spherical Triboelectric Nanogenerators for Harvesting Environmental Energy. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001669.

- Chen, G.; Xu, L.; Zhang, P.; Chen, B.; Wang, G.; Ji, J.; Pu, X.; Wang, Z.L. Seawater Degradable Triboelectric Nanogenerators for Blue Energy. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 2000455.