Mounting preclinical and clinical evidence indicates that rewiring the host immune system in favor of an antitumor microenvironment achieves remarkable clinical efficacy in the treatment of many hematological and solid cancer patients. Nevertheless, despite the promising development of many new and interesting therapeutic strategies, many of these still fail from a clinical point of view, probably due to the lack of prognostic and predictive biomarkers. In that respect, several data shed new light on the role of the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN) in affecting the composition and function of the tumor microenvironment (TME) as well as resistance/sensitivity to immunotherapy. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on PTEN functions in different TME compartments (immune and stromal cells) and how they can modulate sensitivity/resistance to different immunological manipulations and ultimately influence clinical response to cancer immunotherapy

- PTEN

- cancer

- immune cells

- immunoevasion

- Introduction

Tumorigenesis is a genetic/epigenetic process driven by oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene inactivation [1]. Phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN) is one of the tumor suppressors most frequently inactivated in human cancer, due to genetic alterations or transcriptional/post-transcriptional inhibition; moreover, even a partial loss of its function (haploinsufficiency) may cause neoplastic transformation [2–4]. Hence, we will refer to either genetic mutations or protein lost as “PTEN-loss” [5]. The PTEN protein mainly acts as a lipid phosphatase, which converts phosphatidylinositol 3, 4, 5 trisphosphate (PIP3) into phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2), counteracting the activity of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and resulting in the inhibition of cell proliferation, survival and migration [2,6].

The regulation of PTEN expression and function in cancer cells is extremely complex and the recognition of its role as a predictive/prognostic biomarker is hampered by the lack of unequivocal methods to ascertain whether the protein is non-functional, or present [4,6,7]. A further, emerging level of complexity is related to the possibility that the loss of PTEN function may directly or indirectly influence not only cancer cell behavior, but also the tumor microenvironment (TME) and immune-infiltrate composition and function [8]. Since the interaction between cancer and stromal/immune cells may result in a tumor-permissive or non-permissive TME, PTEN activity is in a crucial position to control the overall effects of such interactions.

Immune escape represents one of the hallmarks of cancer and can be determined by a combination of relatively low cancer cell immunogenicity and tumor-dependent immunosuppression [9]. The recognition of the role of immune checkpoints, particularly cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen (CTLA)-4 and programmed cell death (PD)-1, has shed new light on the mechanisms of negative regulation of the immune system and opened a new era in the clinical application of immunotherapy in cancer [10,11]. In such a complex scenario, the continuous bidirectional interactions between cancer cells and infiltrating immune/inflammatory cells are dictated, at least in part, by the genetic background of the different cancerous and non-cancerous components. Such interactions, in turn, may crucially determine the sensitivity or resistance to immunotherapeutic approaches and provide novel targets for an effective treatment.

In this review, we focus on the possible implications of PTEN expression and function within different TME compartments (non-cancer cells and soluble factors), in order to better understand potential mechanisms underlying immunotherapy resistance.

- PTEN in Immunoevasion

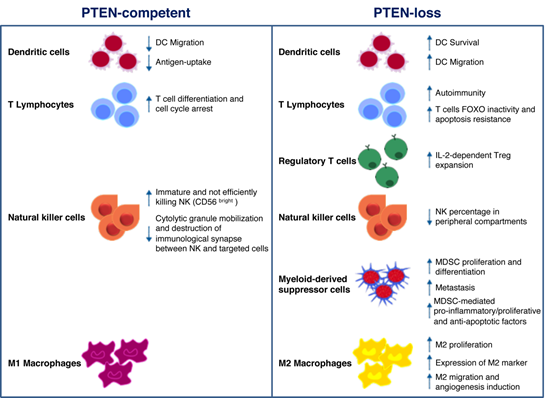

Mounting evidence suggests that PI3K signaling may influence the composition and functionality of the TME, thereby modulating immune response in cancer [46]. In particular, PTEN expression (or lack thereof) in cancer cells attracts different immune cell populations to the TME; on the other hand, PTEN function in immune cells regulates their activation status [8]. As schematically depicted in Figure 1, the overall effect of PTEN loss of function in different cellular compartments shifts the balance towards an immunosuppressive TME [47–49]. Here, we give a comprehensive overview of the potential role of PTEN in the regulation of the immunosuppressive aspects of the TME (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10 (PTEN) function in immune cells. PTEN modulates several microenvironmental stimuli and immune cells processes, according to the cell type in which it is expressed (left panel) or not. As for cancer cells, the lack of PTEN activity mainly correlates with immune escape mechanisms and protumoral immune cells infiltration/expansion (right panel).

2.1. PTEN Role in Immune Cells

DCs are professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) implicated in adaptive immunity, through foreign antigens processing and the subsequent major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-dependent presentation. This mechanism results in the stimulation of naïve T cells and cytotoxic effector cells (i.e., macrophages, NKs) function [50,51]. Failure to effectively present antigens or functional deficiencies in infiltrating DCs contributes to immune suppression [51]. The PI3K pathway plays a key role in DC functions. Indeed, DCs derived from PI3Kγ−/− mice display reduced ability to migrate in response to chemoattractants; similarly, antigen-loaded DCs also show decreased ability to move to lymph nodes [52]. Higher PTEN levels were observed in DCs of elderly, as compared to young, subjects, resulting in reduced AKT activation, antigen-uptake, and DC migration [53]. Based on the above evidence, targeting PTEN in DC-based cancer vaccines could represent a promising approach in immunotherapy. The advantageous effects exerted by the use of PTEN-silenced DCs were related not only to increased DC survival and CCR7-dependent migration, but also to enhanced CD8+ numbers [54]. Pan and collaborators demonstrated that PTEN cooperates in the negative regulation of Dectin-1 and FcεRI γ-chain (FcRγ)-mediated signaling. FcRγ represents an adapter of immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) on DCs and Dectin-1 is a receptor containing an ITAM-like domain involved in DC function in the immune response. Though mostly implicated in antifungal response and leucocyte recognition, the authors underline the importance of PTEN-mediated negative regulation and hypothesize that PTEN targeting may be used as a strategy for the development of new cancer therapy approaches [55].

By modulating antigen receptor expression and cytokine release, PI3K signaling represents a central hub in the regulation of normal T cells differentiation into either cytotoxic CD8+ or helper CD4+. As a consequence of PIP3 production and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 2 phosphorylation, the transcription factor forkhead box (FOX)O translocates from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, resulting in the decreased expression of genes involved in cell cycle arrest and T cell differentiation [56]. PTEN-loss results in a persistent FOXO inactivation and resistance to apoptotic cytokine-mediated signaling, as often detected in hemangiomas and leukemias [57]. Moreover, PTEN heterozygous (PTEN+/−) mice are deficient in Fas-mediated apoptosis: as the binding of Fas (also known as CD95) to its ligand (FasL) is the main mechanism by which CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells kill non-self-cancer cells, PTEN haploinsufficiency results in lymphoid hyperplasia and tumor growth [58,59]. In CD4+ helper T cells, on the other hand, PTEN expression patterns result in opposite effects, according to the timing of PTEN gene inactivation. Indeed, thymocyte-specific PTEN deletion causes lymphomas and autoimmunity, whereas activated T cells hyper-proliferate and over-express cytokines in the presence of PTEN-loss [60,61].

PI3K signaling also regulates CD4+ regulatory T cell (Treg) functions. After T cell receptor engagement and cell activation, PTEN is down-regulated, and this results in interleukin (IL)-2 dependent PI3K signaling and Tregs expansion. On the other hand, IL-2 is able to promote PI3K pathway activation, despite high levels of PTEN, leading to T cell anergy. Overall, the loss of PTEN function cooperates with CD25 stimulation by IL-2 to promote Treg proliferation in a clinical setting [62,63]. PTEN expression may also inhibit T cell response through intercellular binding of PD-1/neurophilin-1 (Nrp-1) and PDL-1/semaphorin-4 (Sema4a) on Tregs and effector cells surface, respectively. As demonstrated by Francisco and coworkers, PD-1 upregulation attenuates PI3K activation during Tregs maturation [64]. It has also been demonstrated that the Sema4a/Nrp1 axis attenuates Tregs-mediated antitumor immune response: the binding of the ligand Sema4a, expressed on immune cells, prevents AKT activation through PTEN-dependent FOXO3a nuclear localization [65]. Another immunosuppressive mechanism, potentially influenced by PTEN, is mediated by the indoleamine 2, 3-dioxigenase (IDO) enzyme, which prevents tryptophan-mediated immunological stimulus and promotes kynurenine-dependent immune effector cells disruption. Intricate feedback signals exist, by which IDO cooperates with PD-1 to promote an immunosuppressive Tregs phenotype. IDO expression in DCs and APCs activates PTEN signaling in Tregs, thus blocking the PI3K cascade and increasing the activity of FOXO1 and FOXO3a, which in turn upregulate PD-1 and PTEN [66]. PTEN inactivation after PD-1 blockade abrogates FOXO-dependent immunosuppression and results in cancer regression [67–69].

CD56+/CD3− large granular NK cells recognize and destroy both infected and transformed cells. A variety of activating stimuli is necessary to fully activate the NK cytotoxicity: once activated, NK cells release perforin, granzymes, and antitumoral immune response-promoting cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α) and induce apoptosis of targeted cells, through FasL/Fas or TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)/TRAIL receptor interactions [70]. Consistently, a marked depletion of their number/activity correlates with increased risk of developing cancer and cancer progression [60]. Immature CD56bright NK cells express higher levels of PTEN, as compared to cytotoxic, CD56dim cells, suggesting a specific role of PTEN in NK cytotoxicity. In this context, PTEN disrupts the immunological synapses between NKs and targeted cells, by decreasing actin accumulation, polarization of microtubules and cytolytic granule mobilization [71]. Another group demonstrated that PTEN is also involved in NK activity by affecting their trafficking and localization in vivo. Indeed, the authors showed a decreased percentage of mature NK cells in peripheral compartments in PTEN-knock out (ko) NK mice [72]. Finally, PTEN is a central player in NK cells activation, through inhibition of the PIP3-mediated signaling cascade (extensively revised in [73]).

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are among the key actors involved in mediating tumor escape mechanisms in the TME, due to their specific ability to abolish T cell and NK functions [74,75]. It has been demonstrated that a complex network of micro-RNAs (miRs) regulates MDSCs activation and functions in the TME, thus opening new scenarios for novel immunotherapy approaches [76]. Tumor-derived transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 upregulates miR-494, which in turn regulates MDSCs activity and localization. PTEN is a direct target of miR-494 and its downregulation, with the consequent activation of PI3K pathway, is involved not only in C-X-C chemokine receptor (CXCR)4-mediated MDSCs chemotaxis towards tumors, but also in metastases formation due to upregulation of metalloproteinases (MMP) (e.g., MMP2, MMP13) [77]. Moreover, TGF-β is also involved in modulating MDSCs expansion through the inhibition of PTEN and SH-2 containing inositol 5′ polyphosphatase (SHIP)1. TGF-β-treated bone marrow-MDSCs display lower levels of PTEN and SHIP-1, regulated by miR-21 and miR-155 respectively, and higher levels of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3: all these perturbations result in an increased number of MDSCs [78]. Several authors also elucidated the importance of the PTEN mRNA 3′UTR as the “seed sequence” recognized by specific miRs, in the regulation of MDSC proliferation and activity [79,80]. Mei and collaborators demonstrated that, among the soluble factors produced by tumor cells, the granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor is the main inducer of miR-200c. This miR is involved in the upregulation of MDSC-immunosuppressive functions and proliferation, by directly targeting the 3′UTR of both PTEN and friend of Gata 2 (FOG2). Inhibition of PTEN and FOG2, in turn, activates PI3K leading to the MDSC differentiation, and STAT3, involved in the production of pro-inflammatory, pro-proliferative and anti-apoptotic factors [79]. Interestingly, tumor-derived exosomes may exert similar effects on PTEN regulation in MDSCs. Indeed, miR-107 delivered by gastric cancer-derived exosomes exerts its activity by inhibiting the functions of PTEN and Dicer1, through the binding to the 3′UTR region, thus resulting in MDSC proliferation and acquisition of ARG-1-mediated suppressive function [80,81]. Similarly, glioma-derived exosomes act as shuttles for miR-21: the consequent inhibition of PTEN and activation of STAT3 promote bone marrow-derived MDSC proliferation and differentiation. Moreover, PTEN-silenced MDSCs upregulate the production of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 [81].

Macrophages are conventionally classified into two categories according to the membrane receptors and their functions: M1 and M2 (or tumor-associated macrophages—TAM), endowed with tumor-suppressor and tumor-promoting properties, respectively. M2 macrophages are the most represented leukocytes in cancer stroma, representing up to 50% of the immune cells in the TME [46]. Li and colleagues showed that PTEN-silencing in macrophages causes an increased release of C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A, promoting the M2 phenotype switch [82]. Moreover, PTEN deletion results in the expression of specific M2 markers, such as the immunomodulating protein arginase I [83]. By enhancing arginase I, M2 macrophages reduce T cell proliferation, hence promoting T cell anergy [84]. A recent paper demonstrated that PTEN expression, regulated by miR networks, can modulate macrophage polarization. Supernatants derived from human glioblastoma cells upregulated miR-32, which in turn interacts and suppresses PTEN in an in vitro model of human monocytes, thus promoting the M2 phenotype and resulting in an enhanced cell proliferation [85]. miR-21 reduces the expression of PTEN and its upstream positive regulator miR-200c in primary macrophages, promoting their differentiation into M2 [86]. Exosomes derived from pancreatic cancer cells promote hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF)-1α/HIF-2α-dependent M2 phenotype through PTEN regulation: miR-301a-3p converts stromal macrophages into M2 macrophages and promotes lung metastases formation by blocking PTEN transcription [87]. Hypoxic lung tumors release miR-103a which blocks PTEN activity: the consequent PI3K/AKT activation induces M2 polarization, with high ability to migrate and regulate angiogenesis [88]. In a very intricate bidirectional crosstalk between cancer cells and the surrounding TME, under hypoxic conditions, epithelial ovarian cancer TAMs release miR-223, which in turn regulates PTEN, promoting ovarian cancer cell proliferation and drug resistance, through PI3K activation [89].

2.2. PTEN Role in Stromal Cells

PTEN genetic inactivation in fibroblasts has extensively been studied in breast cancer [90–92]. Trimboli and coworkers demonstrated that PTEN-loss in fibroblasts results in an increased incidence of HER2-driven breast tumor, innate immune cells infiltration and VEGF-dependent angiogenesis. Indeed, PTEN-loss results in Ets2 phosphorylation and inactivation, thus allowing for the activation of a specific transcriptional program, associated with a more aggressive tumor behavior [90]. Moreover, the lack of PTEN in mammary stromal fibroblasts is associated with modulation of both fibroblasts and other surrounding TME cells. PTEN-loss modifies the oncogenic secretome through the downregulation of miR-320, hence reprogramming both endothelial and epithelial cells towards a more malignant phenotype [91]. The specific deletion of PTEN in murine fibroblasts promotes collagen deposition and parallel alignment of cellular matrix (a feature observed also in patients with breast cancer) even in the absence of cancer cells. Furthermore, PTEN-loss in fibroblasts fosters cancer-associated fibroblasts-like behaviors, such as upregulation of α-smooth muscle actin and MMP activity [92]. Mechanisms of PTEN inactivation have been investigated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), using high throughput techniques. A recent study showed a surprisingly high percentage (40%) of PTEN-loss (due to partial deletion of chromosome 10) in stromal cells, while PTEN loss of heterozygosity was observed in 46.6% of tumors and juxta-tumoral stroma in PDAC patients. In addition, miR-21 overexpression in juxta-tumoral stroma cooperates with PTEN inactivation, even in the absence of PTEN mutations. These observations correlate with aggressive tumor features and worse prognosis [93]. PTEN-loss in PDAC fibroblasts is usually associated with the ablation of the smoothened (Smo) gene, resulting in PTEN degradation by the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF5: proteasome-dependent PTEN inactivation leads to increased proliferation and reduced overall survival (OS) [94].

As widely recognized, PTEN also modulates angiogenesis [95]. Tian and collaborators demonstrated that transfection of HepG2 cells with wild type (wt) PTEN suppresses the expression of VEGF in a HIF-1-dependent manner. Transfection with a PTEN construct lacking the C2 phosphatase domain also resulted in downregulation of both VEGF and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo, albeit to a lesser extent as compared with the complete PTEN construct. This evidence suggests a possible cooperation between phosphatase-dependent and -independent PTEN functions in regulating angiogenesis [96]. The tight link between PI3K/PTEN activation and VEGF was also investigated by our group: indeed, we demonstrated that the hyperactivation of PI3K pathway leads to HIF-1/2 translation and subsequent expression of VEGF [97]. Dong and collaborators showed that PTEN-defective melanoma cell lines express several cytokines, including VEGF, and their expression is transcriptionally inhibited by the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 [98]. A similar correlation was identified also for another pro-angiogenic factor: de la Iglesia and co-workers demonstrated that STAT3-dependent IL-8 expression occurs only in PTEN-loss glioblastoma contexts [99].

2.3. Tumor PTEN Affects Immune Infiltrate

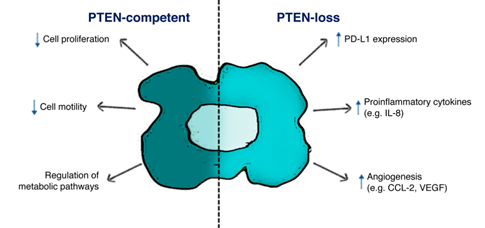

A wealth of evidence suggests a central role of tumor PTEN status in modulating the TME immune infiltrate and cancer cells/TME interactions in different tumor histotypes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of PTEN function in tumor cells. PTEN-status in cancer cells affects both biological features in cancer cells survival and tumor microenvironment (TME) composition, according to the expression of specific ligands (i.e., PD-L1) and soluble factors (i.e., IL-8, CCL-2, VEGF).

In mice and human lung squamous cell carcinoma, the TME of PTEN-loss samples is characterized by the specific accumulation of tumor-associated neutrophils and Tregs, involved in different processes such as angiogenesis and immunosuppression. Moreover, low levels of TAMs, NKs, T and B cells during tumor progression were observed according to increasing tumor burden [100]. In vitro experiments in PTEN-silenced triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) show that low levels of infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are due to the induction of apoptotic mechanisms associated with PD-L1 expression and PTEN-loss [101]. In many instances, tumor genetic background, PTEN-loss in particular, shapes an immunosuppressive TME through the production of specific soluble factors, which in turn modify stromal/immune cells infiltration. Data from our and other groups suggest that PTEN-loss in prostate epithelium, glioblastoma and colorectal cancer (CRC) cells promotes a selective increase in IL-8 expression [99,102–105]. IL-8 production, in turn, correlates with an immunosuppressive, myeloid-enriched, TME and unequivocally with an adverse cancer prognosis, particularly for patients undergoing immunotherapy. In CRC patients, serum IL-8 levels are associated with activation of a gene expression program which enforces a monocyte-/macrophage-like phenotype in CD4+ T cells [106]. FOXP3 CD4+ Tregs markedly express the IL-8 receptor CXCR1, in order to respond to tumor-derived IL-8 and migrate in cancer tissue, and CD4+ T cells produce IL-8 themselves [107,108]. On the other hand, CXCR1 expression is downregulated on CD8+ T cells after antigen presentation, thereby reducing the number of cytotoxic T cells [109]. Interestingly, a recent paper reported that mesenchymal stem cells release IL-8, which activates c-Myc via STAT3 and mTOR signaling in gastric cancer cells, hence resulting in membrane PD-L1 overexpression and blockade of cytotoxic effects of CD8+ T cells. In this complex crosstalk between different cell population, neutralizing IL-8 could enhance the efficacy of PD-L1 antibodies [110]. In a cohort of 168 resected CRC patients, our group recently demonstrated that PTEN-loss in cancer cells significantly correlates with high levels of tumor-derived IL-8 and low levels of IL-8+ infiltrating mononuclear cells (Conciatori 2020, unpublished data, [103]).

Toso and coworkers showed that in PTEN-loss prostate cancer activation of JAK2 and phosphorylation of STAT3 induce the production of specific chemokines, which recruit an increased number of infiltrating MDSCs [111]. Similarly, in PTEN-loss melanoma xenograft models the upregulated production of soluble factors (e.g., CCL2, VEGF) recruits and/or regulates the function of suppressing immune cells (e.g., immature DCs, MDSCs), thus promoting an immunosuppressive TME. In metastatic melanoma patients, nanostring-based analysis of the TME inflammatory cells showed an 83% reduction in inflammation-related genes associated with the PTEN-loss status of cancer cells [112]. In a HRASG12V/PTEN−/− follicular thyroid carcinoma mouse model immunosuppressive Tregs and M2 macrophages were significantly upregulated. Moreover, cell lines isolated by HRASG12V/PTEN−/− express higher levels of chemotactic factors for MDSCs, T cells and macrophages as compared to BRAFV600E/PTEN−/− tumors, highlighting the tight association between genetic background and tumor immune infiltrate [113]. Tumor genetic background influences immune/inflammatory infiltrate into the TME not only in the primary tumor, but also in metastatic lesions, as demonstrated by Vidotto et al. Indeed, the authors showed that in PTEN-loss prostate cancer, higher levels of Tregs were observed in liver metastases as compared to the primary lesion, and high levels of CD8+ cells were present in bone metastases [114]

- Conclusions

Recent advances in immunotherapy (particularly the clinical use of immune checkpoint inhibitors) represent a turning point in the fight against cancer. However, mechanisms of immune escape and acquired resistance to immunotherapy hamper therapeutic efficacy resulting in treatment failure in a substantial proportion of patients. In that respect, certain genetic tumor characteristics, such as the lack of expression of the tumor suppressor PTEN, are of particular interest, due to their involvement in modulating both the tumor and the immune cell compartments of the TME towards an aggressive, therapy-resistant phenotype. Comprehensive PTEN status analysis could be crucial to refine the prediction of response to therapy in individual patients and to define new combinatorial approaches.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms21155337