Northern pike are an invasive species in southcentral Alaska and have caused the decline and extirpation of salmonids and other native fish populations across the region. Northern pike control actions are tailored to the unique conditions of waters prioritized for their management, and all efforts support the goal of preventing further spread of this invasive aquatic apex predator to vulnerable waters.

- suppression

- eradication

- rotenone

- fishery restoration

- northern pike

- salmon

1. Introduction

Illegal introductions of pike have expanded their range in several countries in Europe and Africa, southwestern British Columbia, and throughout the American west including southcentral Alaska. Though most of Alaska falls within the native range for pike, Southcentral Alaska does not have any natural populations [1][2]. Pike generally occupy relatively shallow vegetated lakes, flooded wetlands, low-gradient rivers and backwater sloughs [3].

Pike are opportunistic apex predators that are primarily piscivorous but will also prey on small mammals, waterfowl, amphibians, and invertebrates. Where pike are not a native species, they have the capacity to both directly and indirectly alter freshwater fish communities [4][5][6], especially in waters providing optimal pike spawning and rearing habitat [7]. An effect repeatedly documented following pike introduction is the population-level loss of economically vital fish species [8][9]. Negative ecological and economic impacts such as these classify pike as an invasive species [10] in waters outside its native range [7].

There are a variety of factors that contribute to the invasion success of pike such as its trophic adaptability [11][12] broad physiochemical tolerances [13][14][15], high fecundity [15], ability to achieve high populations densities [16][17], and popularity as a fishing commodity [18][19][20].

2. Ecological Role of Pike in Alaska

Pike occupy a top predator niche in all waters they occur in whether native or non-native [9]. In their native range, pike naturally play a pivotal top-down role in shaping freshwater fish assemblages in shallow low-flow habitats with abundant macrophytes [21].

Pike tend to display a high affinity for macrophyte beds, littoral regions, and outlet streams of individual lakes such that it can take decades for new populations to fully occupy suitable habitat within a drainage [22].

Further upstream, where juvenile salmonids had been extirpated, pike diets were dominated by Arctic lamprey Lethenteron camtschaticum Tilesius 1811, Pacific lamprey Entosphenus tridentatus Richardson 1836 and slimy sculpin, illustrating pike’s trophic adaptability following depletion of targeted prey sources [12].

Bioenergetics models demonstrated that pike could consume up to 1.10 metric tons of juvenile salmonid prey in Alexander Creek annually, which far exceeds the salmonid prey base in the system [8]. This predicted the complete loss of the Chinook salmon stock without management intervention to reduce pike abundance and predation.

he impacts of pike across all SC Alaska waters has been highly variable. This is generally explained by the degree of habitat complexity and connectivity across invaded waters [7][5][12][21].

Presently, pike remain restricted to only a proportion of their available habitat in SC Alaska, but many drainages and salmon populations remain highly vulnerable to pike invasion [23].

3. Management Approaches

Given the impacts to native fish populations that have already been incurred in SC Alaska and the potential for further impacts, management efforts have been underway to mitigate the damages. Most invasive pike management activities are conducted by or are in consultation with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG) and directed through management plans [24][25]. Most invasive pike management projects are prioritized using an ADFG-developed scoring matrix designed to ensure that proposed efforts will maximize restoration benefits to impacted fisheries and prevent further invasion of pike to vulnerable waters. The primary functional areas of invasive pike management in SC Alaska include population suppression, eradication, outreach and angler involvement, and research.

3.1. Population Suppression

Population suppression is a common strategy employed for invasive fish management when eradication of an entire population is not feasible [26][27][28][29].

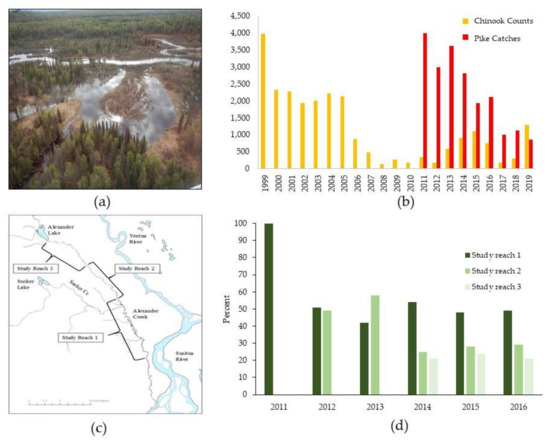

To prevent this, ADFG conducts an annual program that began in 2011 to reduce pike abundance in the optimal pike habitat of side-channel sloughs along Alexander Creek (Figure 1a). The primary objective is to bolster salmon productivity in the system to sustainable levels [30] by reducing pike predation on juvenile salmon. Each May, during the pike spawning period, gillnets (1.8 m by 35.6 m, variable mesh 1.9 cm–5.1 cm) are systematically fished in approximately 60 sloughs. From 2011–2018, sloughs were fished until they achieved 80% reduction in pike catch from their first day’s catch [31].

Between 2011 and 2019, 20,446 pike were removed from Alexander Creek sloughs. During the first three years of suppression between 3000 and 4000 pike were removed annually, but annual pike removal has trended downward since, with less than 1000 pike removed in 2019 (Figure 1b). With the exception of the period between 2016 and 2018, Chinook abundance has trended upward since pike suppression began (Figure 1b).

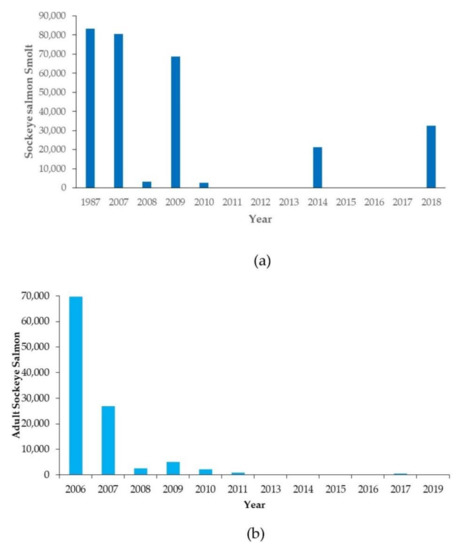

Due to a notable decline in weir counts of sockeye smolt leaving Shell Lake since 2010 (Figure 2) and a similar trend in adult returns, CIAA initiated pike suppression efforts to reduce predation pressure on smolt. The project included several components including smolt and adult sockeye enumeration, sockeye stocking with Shell Lake brood stock, disease screening, pike suppression, beaver dam modifications, and evaluating the effect of pike suppression on sockeye and pike abundances in the lake.

The 2014 smolt release occurred prior to major pike suppression and resulted in the outmigration of only 25% of the released smolt. Diet data taken from captured pike in 2014 showed that the northern pike in Shell Lake stopped preying on most other prey items and focused heavily on smolt when they were available [32][33][34].

Pike diet analyses documented that juvenile salmon dominated pike diets during outmigration, sockeye prey size was positively correlated with pike predator size, and 67% of the depredated sockeye smolt were consumed by pike less than 30 cm (fork length). Bioenergetics estimates of sockeye smolt survival resulting from pike suppression activities suggested a potential increase of over 13,000 adult sockeye [35].

In total, 5087 northern pike from Whiskey Lake were removed between 2012–2019, reducing CPUE from a high of 2.6 pike/gillnet h in 2012 to 0.45 pike/gillnet h in 2019. In Hewitt Lake, 1712 pike have been removed during this period reducing the CPUE from 1.75 pike/gillnet h in 2012 to 0.34 pike/gillnet h in 2019.

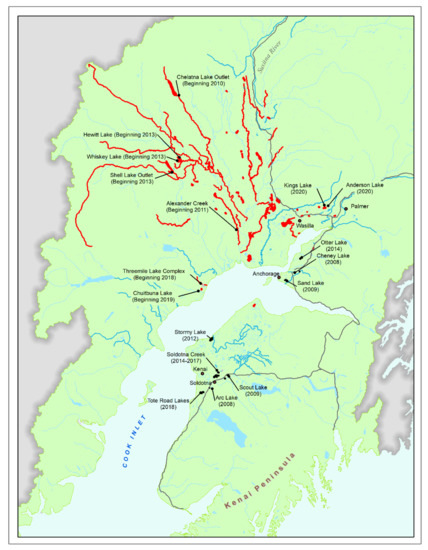

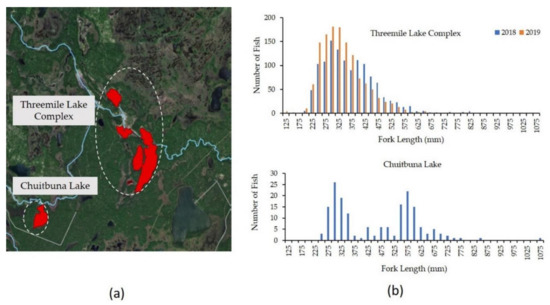

Finally, in 2018 and 2019, new pike suppression programs were initiated in the Threemile Lake complex and Chuitbuna Lake, respectively, on the west side of Cook Inlet [36][37] (Figure 3 and Figure 4a).

The west side Cook Inlet pike suppression sites were conducted in partnership between ADFG the Tyonek Tribal Conservation District (TTCD) and the Native Village of Tyonek (NVT) to increase capacity for pike suppression in a remote region of pike’s invaded range in SC Alaska.

3.2. Population Eradication

Although many of the invasive pike management activities in SC Alaska rely on suppression in complex interconnected drainages, the preferred alternative when possible is to eradicate pike populations entirely.

At present, there are few management tools that can effectively lead to eradication of invasive fish populations. In rare cases, fish populations from very small lakes can be eradicated with gillnets [38].

The most common method used for invasive fish eradications worldwide is through chemical treatments using piscicides, particularly liquid and powdered formulations of rotenone [39].

Rotenone treatment success is confirmed through a combination of gillnetting, including under-ice net sets, observations of caged sentinel fish, analytic determination of rotenone concentration achieved and eDNA detection methods [92,93]. Post-treatment, lakes are monitored through routine surveys to ensure pike are not reintroduced [94]. Once rotenone treatments are complete and post-treatment assessments have confirmed successful pike eradication, fisheries are restored to the treated lakes.

An issue with rotenone projects that is often contentious with the public is concern for piscivorous waterfowl. While these animals are not affected directly by the piscicide, loss of fish prey can displace their populations.

3.3. Outreach and Angler Engagement

3.4. Population Monitoring and Research

The final tenant of invasive pike management in SC Alaska involves monitoring of pike populations throughout the region and conducting research to learn more about the impacts of pike and effective management tools. Research on pike has been on-going over the last decade and, as has been discussed throughout this review, has included investigations into pike diets and impacts [12,16,50] movement patterns [44,45], population genetics [35], predicting invasion risk [35], developing eDNA tools for pike [92,93,103], and better understanding the degradation process of rotenone [UAA Unpublished]. All these investigations are highly collaborative among ADFG, the University of Alaska, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as well as local NGOs like the National Fish Habitat Partnerships (NFHP), Kenai Watershed Forum (KWF), CIAA, TTCD, and NVT. Future research will seek to expand alliances with commercial fisherman to acquire samples of pike caught in estuarine waters for otolith microchemistry investigations to learn how pike may be utilizing Cook Inlet for their current dispersal and to develop barrier designs to protect vulnerable drainages from that occurrence. Research will continue to evaluate effectiveness of current pike suppression efforts and look toward the future to determine what new tools and technologies might emerge, such as those in the genetics realm [104,105,106,107], that may have future applications for adaptive pike management in SC Alaska.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, invasive northern pike in SC Alaska have had complex, and in many cases, severe consequences for native fish populations. Pike are certainly not the only factor responsible for salmon declines in the state, but in some cases, they are a substantial part of that story. In an age of climate change and deteriorating ecological conditions, progressive action to reduce stressors facing salmon and other native fish species in Alaska’s freshwaters is imperative. Alaska is fortunate to not suffer many of the invasive species impacts that are rampant elsewhere, but there is no guarantee that good fortune will continue. As has been well documented with pike, invasive species are a threat to Alaska’s fragile salmon habitats, and pike in SC is one factor that can be mitigated with effective and well prioritized adaptive management.

In this past decade of invasive pike management, significant strides were made toward pike eradication on the Kenai Peninsula and the Anchorage areas. Thousands of pike have been removed from large drainages in the Susitna Basin resulting in increased survival of rearing salmon. Over the last decade close to $5 Million has been spent on these efforts, but the economic value of fisheries in the state is far greater and the cultural value is immeasurable. The invasion and subsequent control efforts for pike in SC Alaska are the most spatially expansive in the world for this species making both the problem and the collaborative program to address it unique. However, there are other locations with similar challenges with invasive populations of pike. Among the most significant examples in the western Unites States are the eastern Columbia River Basin in Washington State and the Yampa River in Utah and Colorado. Significant efforts are underway in these locations to protect native species from pike predation and prevent pike from expanding their ranges. In the Columbia River, this is particularly important as downstream expansion of pike is anticipated to affect anadromous salmon populations just as they have in SC Alaska. In this regard, there is great benefit for western states with invasive pike challenges to collaborate so that successful methods and technologies can be broadly applied. Over the last decade, Alaska’s invasive pike program has contributed to a greater understanding of predation impacts on salmonids and other native fish, helped develop enhanced detection capabilities (i.e., eDNA), pioneered largescale pike suppression (i.e., Alexander Creek), and completed over 20 successful eradications of invasive pike populations.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/fishes5020012

References

- Lever, C. Naturalized Fishes of the World; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996.

- Welcomme, R.L. International Introductions of Inland Aquatic Species; TP No. 294; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1988; pp. 112–113.

- Inskip, P.D. Habitat Suitability Index Models: Northern Pike; FWS/OBS 82/10.17; United States Fish and Wildlife Service: Daphne, AL, USA, 1982.

- Persson, A.P.A.N.; Brönmark, C. Trophic interactions. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 185–211.

- Heins, D.C.; Knoper, H.; Baker, J.A. Consumptive and non-consumptive effects of predation by introduced northern pike on life history traits in threespine stickleback. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2016, 17, 355–372.

- Byström, P.; Karlsson, J.; Nilsson, P.A.; Van Kooten, T.; Ask, J.; Olofsson, F. Substitution of top predators:effects of pike invasion in a subarctic lake. Freshw. Biol. 2007, 52, 1271–1280.

- Dunker, K.J.; Sepulveda, A.; Massengill, R.; Rutz, D. The northern pike, a prized native but disastrous invasive. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 356–398.

- Sepulveda, A.J.; Rutz, D.S.; Dupuis, A.W.; Shields, P.A.; Dunker, K.J. Introduced northern pike consumption of salmonids in Southcentral Alaska. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2014.

- McKinley, T. Survey of Northern Pike in Lakes of Soldotna Creek Drainage, 2002; Special Publication No. 13-02; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2013.

- Beck, K.G.; Zimmerman, K.; Schardt, J.D.; Stone, J.; Lukens, R.R.; Reichard, S.; Randall, J.; Cangelosi, A.A.; Cooper, D.; Thompson, J.P. Invasive species defined in a policy context: Recommendations from the federal invasive species advisory committee. Invasive Plant Sci. Manag. 2008, 1, 414–421.

- Nilsson, P.A.; Eklöv, P. Finding food and staying alive. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 9–31.

- Sepulveda, A.J.; Rutz, D.S.; Ivey, S.S.; Dunker, K.J.; Gross, J.A. Introduced northern pike predation on salmonids in Southcentral Alaska. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2013.

- Jacobsen, L.; Engström-Öst, J. Coping with environments; vegetation, turbidity and abiotics. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 32–61.

- Craig, J.F. Pike: Biology and Exploitation; Chapman & Hall: London, UK, 1996.

- Raat, A.J.P. Synopsis of Biological Data on the Northern Pike Esox Lucius Linneaeus, 1758; FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 30 Rev. 2; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1988.

- Haugen, T.O.; Vøllestad, L.A. Pike population size and structure: Influence of density-dependent and density-independent factors. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 123–163.

- Mann, R.H.K. The numbers and production of pike (Esox lucius) in two Dorset rivers. J. Anim. Ecol. 1980, 49, 899–915.

- Arlinghaus, R.J.A.; Beardmore, B.; Diaz, A.M.; Hühn, D.; Johnston, F.; Klefoth, T.; Kuparinen, A.; Matsumura, S.; Pagel, T.; Pieterek, T.; et al. Recreational piking—Sustainably managing pike in recreational fisheries. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 288–336.

- Kuparinen, A.H.L. Northern pike commercial fisheries, stock assessment and aquaculture. In Biology and Ecology of Pike; Skov, C., Nilsson, P.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 337–355.

- McMahon, T.E.; Bennet, D.H. Walleye and northern pike: Boost or bane to northwest fisheries. Fisheries 1996, 21, 6–13.

- Spens, J.; Ball, J.P. Salmonid or nonsalmonid lakes: Predicting the fate of northern boreal fish communities with hierarchical filters relating to a keystone piscivore. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2008, 65, 1945–1955.

- Rutz, D.S.; Dunker, K.J.; Bradley, P.T.; Jacobson, C. Movement Patters of Northern Pike in Alexander Lake; Fishery Data Series No. 20-16; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2020; p. 50.

- Jalbert, C.S. Impacts of a Top Predator (Esox lucius) on Salmonids in Southcentral Alaska: Genetics, Connectivity, and Vulnerability. Master’s Thesis, University of Alaska Fairbanks, School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2018.

- ADFG Southcentral Northern Pike Control Committee. Management Plan for Invasive Northern Pike in Alaska; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2007; p. 62.

- Fay, V. Alaska Aquatic Nuisance Species Management Plan; Alaska Department of Fish and Gmae: Juneau, AK, USA, 2002; p. 116.

- Britton, J.R.; Gozlan, R.W.; Copp, G.H. Managing non-native fish in the environment. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 256–274.

- Zelasko, K.A.; Bestgen, K.R.; Hawkins, J.A.; White, G.C. Evaluation of a long-term predator removal program: Abundance and population synamics of invasive northern pike in the Yampa River, Colorado. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2016, 145, 1153–1170.

- Syslo, J.M.; Guy, C.S.; Bigelow, P.E.; Doepke, P.D.; Ertel, B.D.; Koel, T.M. Response of non-native lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) to 15 years of harvest in Yellowstone Lake, Yellowstone National Park. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 68, 2132–2145.

- Syslo, J.M.; Guy, C.S.; Cox, B.S. Comparison of harvest scenarios for the cost-effective supression of lake trout in Swan Lake, Montana. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2013, 33, 1079–1090.

- Cook Inlet Staff. Alexander Creek King Salmon Stock Status and Action Plan, 2020; Report to the Board of Fisheries; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2020; p. 29.

- Rutz, D.S.; Bradley, P.T.; Jacobson, C.; Dunker, K.J. Alexander Creek Northern Pike Suppression, 2011–2018, Alaska; Fishery Data Series No. 20-17; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2020; p. 34.

- Wizik, A. Shell Lake Sockeye Salmon Progress Report 2015; Cook Inlet Aquaculture Association: Soldotna, AK, USA, 2015; p. 49.

- Wizik, A.; Schoen, E.; Courtney, M.; Westley, P. Shell Lake Sockeye Salmon Progress Report 2017; Cook Inlet Aquaculture Association: Soldotna, AK, USA, 2017; p. 63.

- Wizik, A. Shell Lake Sockeye Salmon Progress Report 2018; Cook Inlet Aquaculture Association: Soldotna, AK, USA, 2018; p. 59.

- DeCino, R.; Willette, T.M. Chelatna Lake Pike Suppression; Fishery Data Series No. In Prep; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2020; in prep.

- Dunker, K.; Bradley, P.; Jacobson, C. Threemile Lake Invasive Northern Pike Population Assessment; Regional Operational Plan SF.2A.2018.11; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2018; p. 38.

- Bradley, P.; Jacobson, C.; Dunker, K. Operational Plan: Threemile Lake Invasive Northern Pike Suppression and Chuitbuna Lake Population Assessment; Regional Operational Plan SF.2A.2020.01; Alaska Department of Fish and Game: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2019; p. 28.

- Knapp, R.A.; Matthews, K.R. Eradication of nonnative fish by gillnetting from a small mountain lake in California. Restor. Ecol. 1998, 6, 207–213.

- Finlayson, B.; Skaar, D.; Anderson, J.; Carter, J.; Duffield, D.; Flammang, M.; Jackson, C.; Overlock, J.; Steinkjer, J.; Wilson, R. Planning and Standard Operating Procedures for the Use of Rotenone in Fish Management—Rotenone SOP Manual, 2nd ed.; American Fisheries Society: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2018; p. 176.

- Post, J.R.; Sullivan, M.; Cox, S.; Lester, N.P.; Walters, C.J.; Parkinson, E.A.; Paul, A.J.; Jackson, J.; Shuter, B.J. Canada’s recreational fishereis: The invisible collapse? Fisheries 2002, 27, 6–17.

- Pierce, R.B.; Tomcko, C.M.; Schupp, D.H. Exploitation of northern pike in seven small north-central Minnesota lakes. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 1995, 15, 601–609.