Acinetobacter baumannii is an emerging pathogen, and over the last three decades it has proven to be particularly difficult to treat by healthcare services. It is now regarded as a formidable infectious agent with a genetic setup for prompt development of resistance to most of the available antimicrobial agents. we provide a comprehensive updated overview of the available data about A. baumannii, the multi-drug resistant (MDR) phenotype spread, carbapenem-resistance, and the associated genetic resistance determinants in low-income countries (LIICs) since the beginning of the 21st century.

- A. baumannii

- low-income

- surveillance

- developing countries

- carbapenem-resistance

- MDR

- Syria

- Ethiopia

- COVID-19

1. Introduction

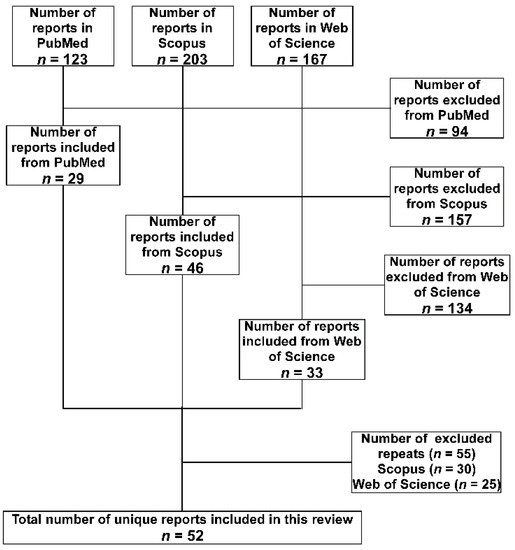

2. Methodology

3. A. baumannii in the LICs Distributed over the Different Geographical Regions

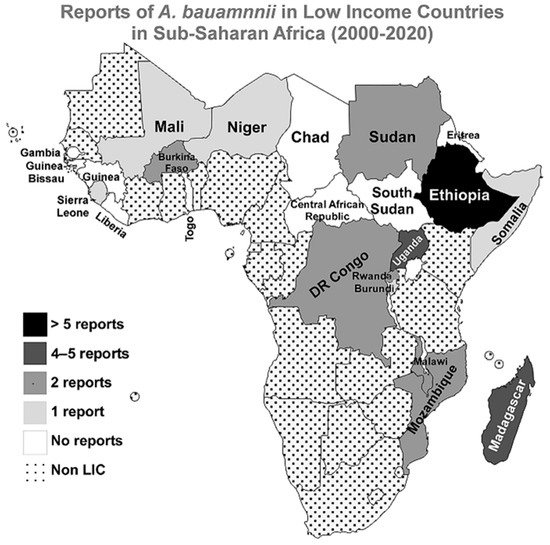

3.1. Sub-Saharan Africa

3.2. Middle East and North Africa

3.3. South Asia

3.4. Latin America and the Caribbean

3.5. Europe and Central Asia

3.6. East Asia and Pacific

| Country | Study | Isolates (n) | MDR % * | CRAB% | Isolates Characterization | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||||||

| Ethiopia | Kempf et al., 2012 | 40 | NA | NA | rpoB and recA sequencing for genotyping | [10] |

| Lema et al., 2012 | 5 | ≥20% | NA | AST with KB | [11] | |

| Pritsch et al., 2017 | 3 | 100% | 100% | AST with KB and VITEK 2, CT102 Micro-Array, real-time PCR, WGS, MLST, and detection of the blaNDM-1 | [12] | |

| Solomon et al., 2017 | 43 | 81% | 37% | AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs and MBLs | [13] | |

| Bitew et al., 2017 | 2 | 100% | NA | Identification and AST with VITEK 2 | [15] | |

| Demoz et al., 2018 | 1 | 100% | 100% | AST with KB | [18] | |

| Gashaw et al., 2018 | 2 | 50% XDR and 50% PDR | 100% | AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs and AmpC | [19] | |

| Moges et al., 2019 | 15 | ≥63% | Yes | AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs and carbapenemases | [14] | |

| Admas et al., 2020 | 6 | 100% | NA | Identification and AST with VITEK 2 | [16] | |

| Motbainor et al., 2020 | 9 | 100% | 33% | Identification with VITEK 2 and AST with KB | [17] | |

| Madagascar | Randrianirina et al., 2010 | 50 | ≥44% | 44% | AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs | [20] |

| Andriamanantena et al., 2010 | 53 | 100% | 100% | AST with KB and MIC determination, phenotypic detection of carbapenemases, ReP-PCR for genotyping and PCR for detection of; blaAmpC, blaoxa51, blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaVIM, blaIMP, and isAba-1 | [21] | |

| Rasamiravaka et al., 2015 | 10 | ≥50% | 0% | AST with KB | [22] | |

| Tchuinte et al., 2019 | 15 | 100% | 100% | MALDI-TOF MS for identification, AST with KB and MIC determination, WGS, MLST for genotyping and WGS detecting; blaoxa51, blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaoxa58, and isAba-1 | [23] | |

| Eremeeva et al., 2019 | 14 | NA | NA | TaqMan PCR of the rpoB for identification, and PCR for detecting: blaoxa51-like, blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaVIM, and blaIMP | [24] | |

| Uganda | Kateete et al., 2016 | 40 | 60% | 38% | AST with Phoenix Automated Microbiology System, PCR for: blaoxa51-like, blaoxa51, blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaoxa58, blaVIM, blaSPM, and blaIMP | [26] |

| Kateete et al., 2017 | 20 | 40% | 35% | AST with MIC determination, PAMS, Rep-PCR for genotyping and phenotypic detection of ESBLs and AmpC | [27] | |

| Moore et al., 2019 | 3 | NA | NA | qPCR TAC | [25] | |

| Aruhomukama et al., 2019 | 1077 | 3% | 3% | AST with KB, PCR for detecting: blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaoxa58, blaVIM, blaSPM, blaKPC, and blaIMP, phenotypic detection of carbapenemases, and conjugation to show transferability of blaVIM. | [28] | |

| Burkina Faso | Kaboré et al., 2016 | 3 | 100% | NA | AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs | [29] |

| Sanou et al., 2021 # | 5 | 100% | 60% | MALDI-TOF MS for identification, AST with KB and MIC determination, phenotypic detection of ESBLs, PCR and sequencing of multiple resistance genes including; blaoxa1-like, blaoxa48-like, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaSPM, blaKPC, blaCTX-M, and blaIMP, and MLST for genotyping. | [30] | |

| DR of the Congo | Lukuke et al., 2017 | 2 | 0% | NA | API for identification and AST with KB | [32] |

| Koyo et al., 2019 | 15 | NA | NA | qPCR and phylogenetic analysis using the rpoB gene | [33] | |

| Malawi | Bedell et al., 2012 | 1 | NA | NA | Identification with standard diagnostic techniques | [34] |

| Iroh Tam et al., 2019 | 84 | ≥44% | NA | API for identification, AST with KB, and phenotypic detection of ESBLs | [35] | |

| Mozambique | Martínez et al., 2016 | 1 | NA | NA | 16S rRNA PCR and MALDI-TOF MS for identification | [37] |

| Hurtado et al., 2019 | 1 | 100% | 0% | 16S rRNA for identification and AST with KB | [36] | |

| Sudan | Mohamed et al., 2019 | 1 | NA | NA | API for identification followed by WGS | [38] |

| Dirar et al., 2020 | 12 | ≥83% | 89% | Identification with PAMS, AST with KB and phenotypic detection of ESBLs and carbapenemases. | [39] | |

| Rwanda | La Scola and Raoult 2004 | 10 | NA | NA | API for identification and recA genotyping | [40] |

| Heiden et al., 2020 | 1 | 100% | 0% | MALDI-TOF MS for identification, AST with VITEK 2, phenotypic detection of ESBLs and carbapenemases, and WGS | [41] | |

| Burundi | La Scola and Raoult 2004 | 3 | NA | NA | API for identification and recA genotyping | [40] |

| Mali | Doumbia-Singare et al., 2014 | 1 | NA | NA | Not mentioned | [42] |

| Sierra Leone | Lakoh et al., 2020 | 14 | ≥40% | 10% | Identification and AST with VITEK 2 | [43] |

| Somalia | Mohamed et al., 2020 | 7 | 100% | 100% | AST with KB | [44] |

| Niger | Louni et al., 2018 | 29 | NA | NA | qPCR and rpoB PCR for identification and phylogenetic analysis | [45] |

| Central African Republic | No Reports | |||||

| Chad | No Reports | |||||

| Eritrea | No Reports | |||||

| Gambia | No Reports | |||||

| Guinea | No Reports | |||||

| Guinea-Bissau | No Reports | |||||

| Liberia | No Reports | |||||

| South Sudan | No Reports | |||||

| Togo | No Reports | |||||

| Middle East and North Africa | ||||||

| Syria | Hamzeh et al., 2012 | 260 | ≥65% | 65% | Identification and AST with PAMS | [46] |

| Teicher et al., 2014 | 6 | 100% | 80% | API for identification and AST with MicroScan Walk-Away System | [47] | |

| Peretz et al., 2014 | 5 | 100% | NA | Not mentioned | [50] | |

| Rafei et al., 2014 | 4 | 100% | 100% | Identification with rpoB sequencing and blaoxa51, PCR, AST with KB and Etest, PCR for: blaoxa23-like, blaoxa24-like, blaoxa58-like, and blaNDM, and PFGE for genotyping | [53] | |

| Heydari et al., 2015 | 1 | 100% | 100% | Identification and AST with VITEK 2, phenotypic detection of ESBLs and carbapenemases, PCR for the blaNDM, PFGE and MLST for typing | [51] | |

| Rafei et al., 2015 | 59 | Yes | 74% | Identification with MALDI-TOF MS, rpoB sequencing and blaoxa51 PCR, AST with KB and Etest, PCR for detecting: blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaoxa58, blaNDM-1, blaVIM, blaoxa143, and blaIMP, and MLST for typing | [54] | |

| Herard and Fakhri 2017 | 38 | NA | NA | Not mentioned | [48] | |

| Salloum et al., 2018 | 2 | 100% | 100% | AST with KB and Etest, PCR for blaoxa58 and blaNDM, plasmid typing with PBRT, MLST, and WGS | [55] | |

| Fily et al., 2019 | 6 | NA | 67% | AST with KB | [49] | |

| Hasde et al., 2019 | 5 | NA | NA | Not mentioned | [52] | |

| Yemen | Bakour et al., 2014 | 3 | 100% | 100% | API and MALDI-TOF MS for identification, AST with KB and E-test, phenotypic detection of carbapenemases, PCR detection of: blaoxa23, blaoxa24, blaoxa58, blaNDM, blaVIM, blaSIM, blaoxa48-like, blaIMP and others, and MLST | [56] |

| Fily et al., 2019 | 1 | NA | 100% | AST with KB | [49] | |

| South Asia | ||||||

| Afghanistan | Sutter et al., 2011 | 57 ¥ | ≥75% | 76% | Identification and AST with MicroScan autoSCAN-4 | [57] |

| Latin America and The Caribbean | ||||||

| Haiti | Potron et al., 2011 | 3 | 66.7% | 0% | API and 16sRNA for identification, AST with KB and E-test, phenotypic detection of ESBLs, PCR for detection of: blaTEM, blaSHV, blaPER-1, blaVEB-1, blaGES-1, and blaCTX-M | [58] |

| Marra et al., 2012 | 1 | 100% | 0% | Identification and AST with VITEK 2 | [59] | |

| Murphy et al., 2016 | 4 | ≥25% | 25% | AST but the method was not indicated | [60] | |

| Chaintarli et al., 2018 | 2 | 0% | 0% | Identification and AST with VITEK 2 and phenotypic detection of ESBLs | [61] | |

| Roy et al., 2018 | 0 ϕ | NA | NA | Metagenomic analyses of water samples | [62] | |

| Europe and Central Asia | ||||||

| Tajikistan | No Reports | |||||

| East Asia and Pacific | ||||||

| Democratic People’s Republic of Korea | No Reports | |||||

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antibiotics10070764