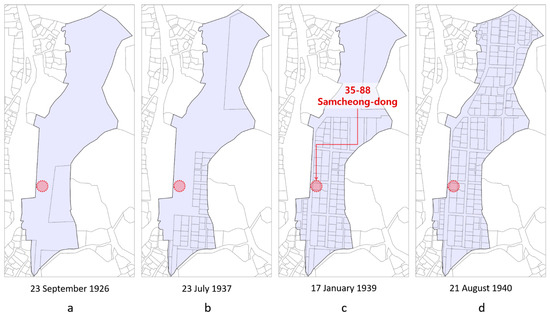

The Samcheong Hanok was first built in Bukchon, specifically, 35-88 Samcheong-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul. Although no direct record of the first construction is available, the construction time can be assumed based on the information regarding housing lot division in the area. One study shows how the housing lot of 35 Samcheong-dong was subdivided between the mid-1920s and early 1940s (

Figure 7) [

15] (pp. 252–253), and we can confirm that the site, 35-88 Samcheong-dong, had been realized by January 1939. The preparation of housing sites and the actual construction of houses in the sites could be separate issues. Nevertheless, it is very likely that the construction of houses followed soon after the housing site preparation, considering the housing shortage in Seoul in the 1930s and responsive active housing development [

3,

4]. Indeed, it was reported that 6000–7000 new houses were built in Seoul between 1933 and 1935, including approximately 4000 in Bukchon [

16]. Therefore, we may assume that the Samcheong Hanok was most likely built in the late 1930s or, at the latest, very early 1940s. Additionally, it seems that the 35 Samcheong-dong area was developed as a residential district by developer Dae-gyu Jung, who owned the land [

4] (pp. 17–18) [

15] (p. 271 and 377). This implies that the Samcheong Hanok is a mass-produced

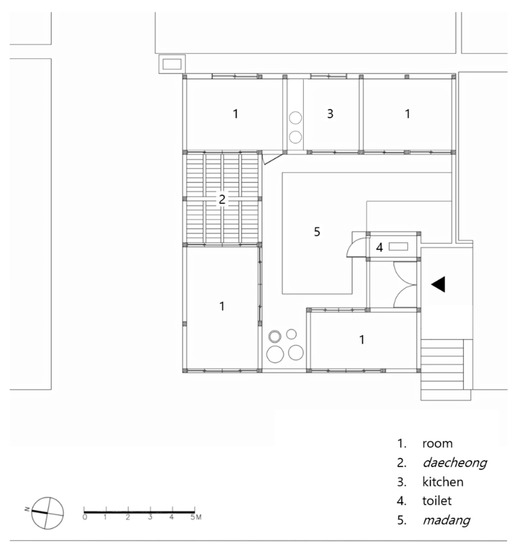

urban-type hanok building, and its floor plan would be typical of such houses. One study illustrated various plans of houses located in one block south of Samcheong Hanok (

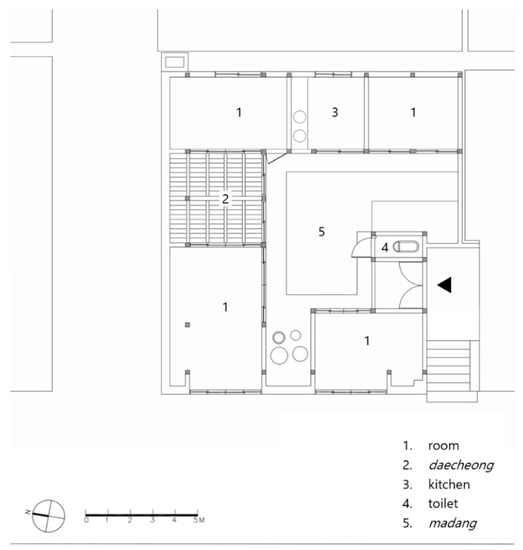

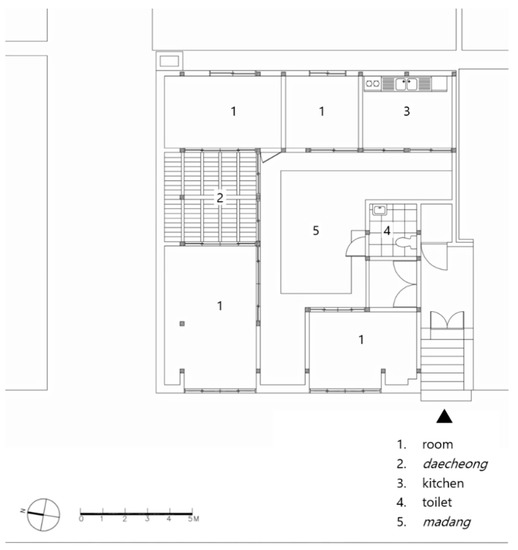

Figure 8), which also belonged to 35 Samcheong-dong. These plans differ from each other in scale and room arrangement but have the typical characteristics of the

urban-type hanok, as described in the previous section of the paper.

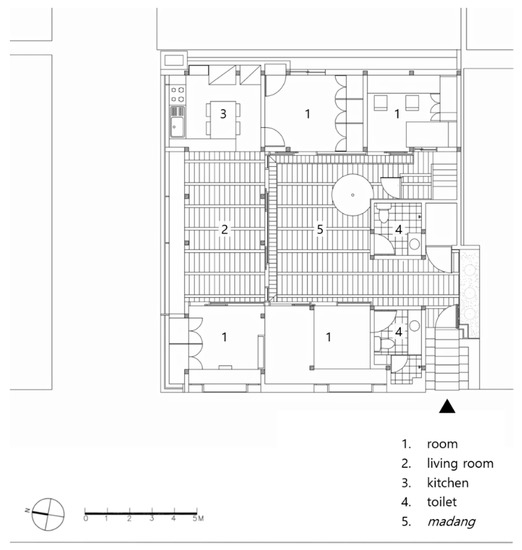

Based on the floor plans of neighboring houses—especially those of a similar size and context to the site—and the pre-renovation drawings made in 2000, this study reconstructed a plausible floor plan of the Samcheong Hanok when first built around 1940. In other words, this presumable first plan (

Figure 9) resulted from the comparison and integration of its two conditions in the late 1930s and late 1990s. We can now re-examine the plan in reverse. The plan is “ㅁ-shaped,” or more specifically “open ㅁ-shaped (「」),” consisting of two “ㄱ-shaped” units. Of course, the

madang is at the center of the plan. Moreover, the building blocks themselves serve as outer walls, dispensing with the traditional independent walls. Hence, these features correspond to the characteristics of the

urban-type hanok. However, the internal room arrangement is uncertain at this stage, and thus, the reconstruction plan inevitably follows the pre-renovation plan as a whole. The resultant composition is that four (

ondol) rooms and the

daecheong, or wooden-floored central hall (of which cool

maru space contrasts with the floor-heated

ondol rooms), along with the kitchen and toilet, surround the

madang. Here, the kitchen was relocated between two rooms in the east wing, differing from the pre-renovation plan; in particular, the traditional type of kitchen with an

agungi fireplace (for cooking and heating) is situated there to warm the

ondol rooms on both sides or, at least, the main room

anbang on the left. A similar room-kitchen arrangement is found in the floor plan of 35-20 Samcheong-dong (

Figure 8). The toilet beside the gate, or at one side of the (minimized)

munganchae, must be an old-fashioned one and rather small in size. To understand details about service spaces such as toilets and kitchens, we could also refer to several contemporary houses with the Samcheong Hanok in 11 Gahoe-dong, located next to Samcheong-dong in Bukchon—the housing lots, and houses themselves, in 11 Gahoe-dong started being developed in 1935 (

Figure 6) [

12] (p. 93) [

15] (p. 229 and 371). However, it seems relatively easy to assume the first state of the house’s structure, compared with that of the spatial composition, because the Samcheong Hanok is a typical

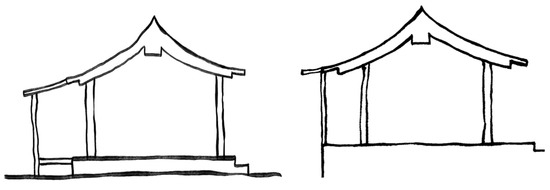

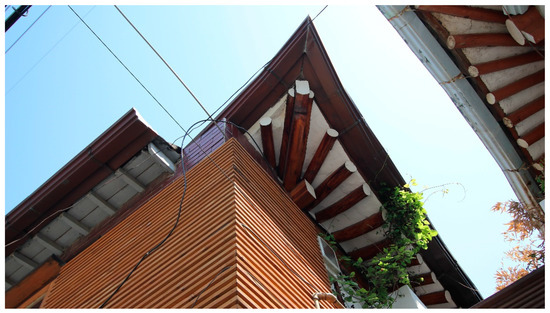

urban-type hanok of the time. It must have had the basic wood-frame structure to support the traditional roof.