Diabetes is a major public health concern that is approaching epidemic proportions globally [1]. About 422 million people worldwide have diabetes, and 1.6 million deaths are directly attributed to diabetes each year. The most common is the type 2 diabetes. In the past three decades, the prevalence of type 2 diabetes has risen dramatically in countries of all income levels [2].

- patient engagement

- food literacy

- diabetes intervention

- chronic disease

1. Introduction

There is substantial evidence that leading a healthy lifestyle, including following a healthy diet, achieving modest weight loss, and performing regular physical activity, can maintain healthy blood glucose levels and reduce the risk of complications of type 2 diabetes [1]. Indeed, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) published guidelines highlighting that self-management and education are crucial aspects of diabetes care allowing the optimization of metabolic control, the improvement of overall quality of life, and the prevention of acute and chronic complications [2]. Given its nature, primary care can be a valuable setting for preventing diabetes and its complications in at-risk populations because it is a patient’s primary point of contact with the health care system. Patients can be offered support by primary care health professionals (e.g., general practitioners, practice nurses) for prevention, such as screening and lifestyle advice, as well as monitoring health outcomes [3]. For these reasons, scholars have been studying how to educate and engage patients in effective behavioral change towards better health outcomes [4][5][6]. The concept of food literacy is recognized in the literature as a fundamental ingredient for the management of chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes [7]. This concept is defined in the literature as the ability to develop knowledge and skills in food management, and it is a multi-componential concept that includes several aspects [8]. In a recent review of the literature [9], authors systematized the various definitions of food literacy, identifying these constitutional components: food skills, food nutritional knowledge, self-efficacy and attitudes towards food, food and dietary behaviors, ecological factors (socio-cultural, influences, and eating practices). This multi-component nature was also highlighted in the review from 2017 by Truman and colleagues [10]. However, both scholars and institutions suggested that knowledge alone is not sufficient to sustain a behavioral change in disease management, but it is necessary to gain a broader perspective that considers patients’ psychosocial aspects and how they contribute to their engagement in the care [11][12][13][14]. Recently, the World Health Organization confirmed the support of a change in this direction with the Shanghai 2016 declaration [15] that promotes both health literacy and empowerment for individuals to enable their participation in managing their health. Over the past 50 years, an extensive body of literature has emerged describing several concepts of the relationship between patients and healthcare systems. In this perspective, the patients are considered as full members of the healthcare team [16] not only with their disease but also with their psychological uniqueness, values, and experience [10][17][18] as the human component of the care. For the patients, to assume an active role in disease management, it means to shift from being a passive user of the healthcare services to being an active partner, emotionally resilient, and behaviorally able to adjust medical advices to their own disease status [14][19][20]. In fact, people with high levels of engagement have been identified as more effective in enhancing behavioral change and in adhering to medical prescriptions [21][22] and in diabetes management [23] and in having an overall better quality of care.

To sum up, in the past decades, the shift towards a more multifaceted approach to patients with diabetes is challenging the public health sector to lever on the patients themselves as the key actors for implementing effective educational interventions. In this scenario, concepts related to patient engagement have been recognized as an essential topic to sustain type 2 diabetes disease-management and prevention behaviors. However, the relative newness of this concept and the fragmentation of articles applying it to food literacy educational interventions in the scientific debate urges for a systematization aimed at providing innovative insights.

In line with these premises, the aim of this systematic review is to map educational intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes in order to promote food literacy, with a particular focus on patient engagement, and to discuss the results about disease complications’ prevention.

2. Analysis on Results

2.1. Overview of the Studies

| ACY | Study Design | Exposure Timing | Outcomes Cathegory | N | Age Intervention (Mean, SD) | Age Control (Mean, SD) | Synthetic Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glasgow, R.E., USA, 2003 | Rct | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 320 | 59; 9.2 | NR | Improvements on behavioural, psychological, and biological outcomes. Difficulties in maintaining website usage over time. |

| Glasgow, R.E., USA, 2006 | Rct | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 301 | 62.0 (11.7) | 61.0 (11.0) | Reduction of dietary fat intake and weight. |

| Among patients having elevated levels of HbA1c or lipids or depression at baseline, promising trend but not significant. | |||||||

| Petkova, V.B., Bulgaria, 2006 | Pre-post study | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 24 | 64.96 (10.18) | NR | Improvement in patients’ diabetes knowledge and quality of life. Decreased frequency of hypo- and hyperglycemic incidents. |

| Song, M., Korea, 2009 | Rct | 2 days program | clinical | 49 | 51.0 (11.3) | 49.5 (10.6) | Reduction of mean HbA1c levels by 2.3% as compared with 0.4% in the control group. Increased adherence to diet. |

| Lujan, J., USA, 2007 | Rct | 8 weekly 2 h group sessions | clinical, psychological, literacy | 150 | 58 | NR | No significant changes at the 3-month assessment. At 6 months, adjusting for health insurance coverage, improvement of the diabetes knowledge scores and reduction of the HbA1c levels. The health-belief scores decreased in both groups. |

| Hill-Briggs, F., USA, 2008 | Rct | 90 min | literacy | 30 | 60.9 (8.9) | 62.1 (11.2) | Knowledge scores increased for below average (BA) and average (A) literacy groups. The BA group showed the largest gains in knowledge about recommended ranges for HbA1c, HDL cholesterol, and goals for CVD self-management. In the A group, the largest gains were found in differentiating LDL as “bad” cholesterol and knowing the recommended range for blood pressure. |

| Wallace, A.S., USA, 2009 | Quasi-experimental | NR | behavioral, psychological, literacy | 250 | 56 | NR | Improvements (similar across literacy levels) in activation, self-efficacy, diabetes-related distress, self-reported behaviors, and knowledge. |

| Hamuleh, M., Iran, 2010 | Rct | 40 min | psychological and literacy | 128 | NA | NA | Using health-belief models for an educational intervention significantly modified benefits and barriers of perception to diet. |

| Hill-Briggs, F., USA, 2011 | Rct | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 56 (29 intensive intervention; 26 condensed intervention) | 61.1 (11.0) | 61.5 (10.9) | Program scored as helpful and easy to understand. At immediate post intervention, participants in both programs demonstrated knowledge gain. At 3 months post intervention, only the intensive intervention was effective in improving knowledge, problem-solving skills, self-care, and HbA1c levels. |

| Carter, E.L., USA, 2011 | Rct | 30 min biweekly | clinical | 47 | 52 | 49 | Improvement in health outcomes and responsibility for self-health together with “other benefits’’. |

| Osborn, C.Y., USA, 2011 | Rct | expected to be completed in 5 days | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 118 | 56.7 (10.1) | NR | At 3-months: increased level of participants reading food labels and improvement in adherence to diet recommendations. No significant differences between the two groups on adjusted group means for physical activity and HbA1c levels. |

| Taghdisi, M.H., Iran, 2012 | Quasi-experimental case-control study | 20–30 min | psychological | 78 | 49 | NR | No significant increase in the mean score of quality of life. Significant differences in physical health, self-evaluation of quality of life, and self-assessment of health. |

| Castejón, A.M., USA, 2013 | Rct | half a day session + 2 × 60 min consultation | clinical | 43 | 55 (10) | 54 (9) | Greater BMI and HbA1c levels reduction. No significant difference in blood glucose, blood pressure, or lipid levels. |

| Swavely, D., USA, 2014 | Pre-post study | 13 h | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 106 | 56.8 (10.4) | NR | Significant improvements in diabetes knowledge, self-efficacy, and three self-care domains, such as diet, foot care, and exercise. At 3 months, levels of HbA1c decreased. No significant improvements in the frequency of blood glucose testing. |

| Calderón, J.L., USA, 2014 | Rct | 13 min video | literacy | 240 | NA | NA | No differences in the increase of DHLS scores occurred in both groups, but when adjusting for baseline DHLS score, sex, age, and insurance status, intervention group performed better. For participants with inadequate literacy levels, health literacy scores significantly increased. |

| Koonce, T.Y., USA, 2015 | Rct | NR | literacy | 128 | 54 (12.1) | 53 (9.6) | DKT results at 2 weeks showed better performance on all literacy domains. |

| Kim, M.T., USA, 2015 | Rct | weekly 2 h sessions × 6 weeks | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 209 | 59.1 (8.4) | 58.3 (8.5) | At 12 months: reduction in HbA1c levels and improvement in diabetes-related self-efficacy and quality of life. |

| Ichiki, Y., Japan, 2016 | Pre-post study | 20 min sessions | clinical | 35 | 73.5 (12.2) | NR | Education was effective in participants with high baseline HbA1c levels (>8%) and poor understanding of their treatment. |

| Protheroe, J. UK, 2016 | Rct | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 76 | 64.7 (11.2) | 61.5 (10.1) | Participants in the LHT arm had significantly improved mental health and illness perception. The intervention was associated with lower resource use, better patient self-care management, and better QALY profile at 7-month follow-up. |

| Bartlam, B. UK, 2016 | Rct | NR | literacy | 40 | 43 | NR | The intervention was acceptable to patients and, additionally, it resulted in behaviour changes. |

| Hung, J.Y., Taiwan, 2017 | Quasi-experimental | 1.5 h × 7 weeks | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 95 | 61.3 (8.0) | 58.5 (9.1) | Improvement in coping with disease and enhancement in self-care ability and positive effects on biochemical parameters, such as BMI, FPG, and HbA1c. DCMP could effectively increase the frequency of weekly SMBG and the DM health literacy levels among Taiwanese DM patients. No significant changes in depressive symptoms. |

| Lee, S.J., Korea, 2017 | Rct | 1 h | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 51 | 74.5 (4.8) | 74.5 (4.8) | Significant differences in DSK, DSE, DSMB, DHB, and HbA1c levels. |

| Wan, E.Y.F., Hong Kong, 2017 | Quasi-experimental | NR | psychological | 1039 | 63.80 (10.61) | 68.54 (10.14) | RAMP-DM was more effective in improving the physical component of HRQOL, patient enablement, and general health condition in patients with suboptimal HbA1c than those with optimal HbA1c. However, the hypothesis that the RAMP-DM can improve HRQOL cannot be fully supported by these research findings. |

| Lee, M.-K., USA, 2017 | Rct | NR | clinical | 198 | 54.6 (9.7) | 56.4 (8.7) | An increased SMBG frequency (twice a day) for the first 6 weeks with the telemonitoring device was associated with improved glycemic control (HbA1c and fructosamine blood levels) at 6 months. |

| Siaw, M.Y.L., Malaysia, 2017 | Rct | 20–30 min | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 330 | 59.2 (8.2) | 60.1 (8.1) | At 6 months: reduction of mean HbA1c, higher in patients with uncontrolled glycemia at baseline. Improvements in PAID and DTSQ scores, reduction in physician workload, and an average cost savings were observed. |

| Every 4 to 6 Weeks | |||||||

| Vandenbosch, J., Belgium, 2018 | Pre-post study | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 366 | 62.1 (11.99) | 62.5 (11.12) | Positive effects of DSME programmes on self-reported self-management behaviours and almost all psychological and health outcomes regardless of HL level. Individual and group-based programs performed better than self-help groups. |

| Kim, S.H., Korea, 2019 | Rct | NR | clinical, behavioral, psychological | 155 | NR | NR | At 9 weeks, patients with high HL showed higher levels of patient activation than those with low HL in the control group, while the difference related to HL was no longer significant in intervention groups. At 9 weeks, patients who received the telephone-based, HL-sensitive diabetes management intervention had a significantly higher score for self-care behaviors. No significance on HbA1c levels. |

| Rasoul, A.M., Iran, 2019 | Rct | 90′ session 3 times a week | psychological | 98 | 31.36 (5.29) | 32.98 (4.42) | Significant differences both in anthropometric variables/metabolic indicators (waist circumference, FBS, BMI) and quality of life score. |

| Cheng, L. China, 2019 | Rct | NR | psychological | 242 | 56.13 (10.72) | 53.9 (13.01) | At one week, significant improvements on empowerment level, reduction in terms of emotional-distress, regimen-distress, and physician-related distress was observed. Empowerment, emotional-distress, and improvement in quality of life were found to be still significant at 3 months. |

| McGowan, P., Canada, 2019 | Pre-post study | 30 min | clinical, behavioral, psychological, literacy | 115 | 60.8 (9.3) | NR | At 12 months: reduction of HbA1c level, fatigue, and depression level; improvement of general health, activation, empowerment, self-efficacy, and increased communication with physician. |

| Hernández-Jiménez, S., Mexico, 2019 | Pre-post study | sessions 30–60 min | clinical | 1837 | 51.1 (10.3) | NR | At 4 months, positive effects on empowerment, HL, anxiety, depression, quality of life, HbA1c levels, BP, and LDL. Decreasing trends were also observed at 12 months. |

| Sims Gould, J., Canada, 2019 | Pre-post study | NR | behavioral, literacy | 17 | NR | NR | The GMVs increased participants’ diabetes literacy and self-management skills |

| White, R.O., 2021 | Rct | NR | behavioral, literacy, clinical, psychological | 364 | 51 (36–60) | 50 (37–60) | At 12 months: decreased risk of poor eating and better treatment satisfaction, self-efficacy, and HbA1c levels. |

2.2. Quality Assessment

| Author (year) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glasgow, R.E. (2003) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Kim, M.T. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Rasoul, A.M. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 |

| Cheng, L. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Protheroe, J. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Bartlam, B. (2016) | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Lujan, J. (2007) | Y | Y | N | U | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 |

| Lee, S.J. (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Hill-Briggs, F. (2011) | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Kim, S.H. (2019) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Glasgow, R.E. (2006) | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Hamuleh, M. (2010) | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Lee, M.K. (2017) | Y | U | Y | U | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Siaw, M.Y.L. (2017) | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Calderón, J.L. (2014) | Y | N | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Song, M. (2018) | Y | N | Y | U | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Castejón, A.M. (2013) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Carter, E.L. (2011) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Koonce, T.Y. (2015) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Osborn, C.Y. (2011) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 |

| Hill-Briggs, F. (2008) | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Wan, E.Y.F. (2017) | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Hung, J.Y. (2017) | Y | Y | Y | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| Wallace, A.S. (2009) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 |

| Taghdisi, M.H. (2012) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Vandenbosch, J. (2018) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Hernández, J.S. (2019) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Swavely, D. (2014) | Y | U | NA | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Petkova, V.B. (2006) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 |

| Sims, G.J. (2019) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| McGowan, P. (2019) | Y | Y | NA | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | 0 |

| Ichiki, Y. (2016) | Y | Y | NA | U | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

| White, R.O., 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | + |

-

Was the research question clearly stated?

-

Was the selection of study subjects/patients free from bias?

-

Were study groups comparable?

-

Was method of handling withdrawals described?

-

Was blinding used to prevent introduction of bias?

-

Were intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure factor or procedure and any comparison(s) described in detail? Were intervening factors described?

-

Were outcomes clearly defined and the measurements valid and reliable?

-

Was the statistical analysis appropriate for the study design and type of outcome indicators?

-

Are conclusions supported by results with biases and limitations taken into consideration?

-

Is bias due to study’s funding or sponsorship unlikely?

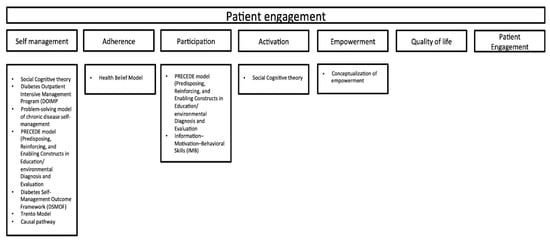

2.3. Outcome Categories

2.3.1. Patient Engagement Components

2.3.2. Intervention Target

2.3.3. Intervention Provider

2.3.4. Theoretical Framework

2.3.5. Intervention Materials

2.3.6. Technology Proxy

2.3.7. Outcome Measure

| ACY | Outcome Categories and Measure Tools |

|---|---|

| Glasgow, R.E., USA, 2003 |

|

| Glasgow, R.E., USA, 2006 |

|

| Petkova, V.B., Bulgaria, 2006 |

|

| Song, M., Korea, 2009 |

|

| Lujan, J., USA, 2007 |

|

| Hill-Briggs, F., USA, 2008 |

|

| Wallace, A.S., USA, 2009 |

|

| Hamuleh, M., Iran, 2010 |

|

| Hill-Briggs, F., USA, 2011 |

|

| Carter, E.L., USA, 2011 |

|

| Osborn, C.Y., USA, 2011 |

|

| Taghdisi, M.H., Iran, 2012 |

|

| Castejón, A.M., USA, 2013 |

|

| Swavely, D., USA, 2014 |

|

| Calderón, J.L., USA, 2014 |

|

| Koonce, T.Y., USA, 2015 |

|

| Kim, M.T., USA, 2015 |

|

| Ichiki, Y., Japan, 2016 |

|

| Protheroe J., UK, 2016 |

|

| Bartlam B.,UK, 2016 |

|

| Hung, J.Y., Taiwan, 2017 |

|

| Lee, S.J., Korea, 2017 |

|

| Wan, E.Y.F., Hong Kong, 2017 |

|

| Lee, M.-K., USA, 2017 |

|

| Siaw, M.Y.L., Malaysia, 2017 |

|

| * Vandenbosch, J., Belgium, 2018 |

|

| Kim, S.H., Korea, 2019 |

|

| Rasoul, A.M., Iran, 2019 |

|

| Cheng, L. China, 2019 |

|

| McGowan, P., Canada, 2019 |

|

| Hernández-Jiménez, S., Mexico, 2019 |

|

| Sims Gould, J., Canada, 2019 |

|

| White, R.O., 2021 |

|

4. Current Insights

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jpm11080795

References

- Chong, S.; Ding, D.; Byun, R.; Comino, E.; Bauman, A.; Jalaludin, B. Lifestyle Changes After a Diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 43–50.

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care 2020, 43 (Suppl. 1), S14–S31.

- Messina, J.; Campbell, S.; Morris, R.; Eyles, E.; Sanders, C. A Narrative Systematic Review of Factors Affecting Diabetes Prevention in Primary Care Settings. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177699.

- Vandenbosch, J.; Van den Broucke, S.; Schinckus, L.; Schwarz, P.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Muller, I.; Levin-Zamir, D.; Schillinger, D.; Chang, P.; et al. The Impact of Health Literacy on Diabetes Self-Management Education. Health Educ. J. 2018, 77, 349–362.

- Cheng, L.; Sit, J.W.H.; Choi, K.; Chair, S.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Long, J.; Yang, H. The Effects of an Empowerment-Based Self-Management Intervention on Empowerment Level, Psychological Distress, and Quality of Life in Patients with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103407.

- Lee, S.J.; Song, M.; Im, E.-O. Effect of a Health Literacy–Considered Diabetes Self-Management Program for Older Adults in South Korea. Res. Gerontol. Nurs. 2017, 10, 215–225.

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food Literacy: Definition and Framework for Action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145.

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining Food Literacy and Its Components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59.

- Azevedo Perry, E.; Thomas, H.; Samra, H.R.; Edmonstone, S.; Davidson, L.; Faulkner, A.; Petermann, L.; Manafò, E.; Kirkpatrick, S.I. Identifying Attributes of Food Literacy: A Scoping Review. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2406–2415.

- Truman, E.; Lane, D.; Elliott, C. Defining Food Literacy: A Scoping Review. Appetite 2017, 116, 365–371.

- Coulter, A. Patient Engagement—What Works? J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2012, 35, 80–89.

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Bonanomi, A.; Riva, G. Factors Affecting Patients’ Online Health Information-Seeking Behaviours: The Role of the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) Model. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1918–1927.

- Gruman, J.; Rovner, M.H.; French, M.E.; Jeffress, D.; Sofaer, S.; Shaller, D.; Prager, D.J. From Patient Education to Patient Engagement: Implications for the Field of Patient Education. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 78, 350–356.

- Menichetti, J.; Libreri, C.; Lozza, E.; Graffigna, G. Giving Patients a Starring Role in Their Own Care: A Bibliometric Analysis of the on-Going Literature Debate. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 516–526.

- World Health Organization. Promoting Health in the SDGs. In Proceedings of the 9th Global Conference for Health Promotion, Shanghai, China, 21–24 November 2016.

- Wolf, A.; Moore, L.; Lydahl, D.; Naldemirci, Ö.; Elam, M.; Britten, N. The Realities of Partnership in Person-Centred Care: A Qualitative Interview Study with Patients and Professionals. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016491.

- Swanson, V.; Maltinsky, W. Motivational and Behaviour Change Approaches for Improving Diabetes Management. Pract. Diabetes 2019, 36, 121–125.

- Rushforth, B.; McCrorie, C.; Glidewell, L.; Midgley, E.; Foy, R. Barriers to Effective Management of Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care: Qualitative Systematic Review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e114–e127.

- Barello, S.; Graffigna, G.; Vegni, E. Patient Engagement as an Emerging Challenge for Healthcare Services: Mapping the Literature. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 1–7.

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J. What The Evidence Shows About Patient Activation: Better Health Outcomes And Care Experiences; Fewer Data On Costs. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 207–214.

- Hill, A.-M.; Etherton-Beer, C.; Haines, T.P. Tailored Education for Older Patients to Facilitate Engagement in Falls Prevention Strategies after Hospital Discharge—A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63450.

- Greene, J.; Hibbard, J.H. Why Does Patient Activation Matter? An Examination of the Relationships Between Patient Activation and Health-Related Outcomes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 520–526.

- Graffigna, G.; Barello, S.; Libreri, C.; Bosio, C.A. How to Engage Type-2 Diabetic Patients in Their Own Health Management: Implications for Clinical Practice. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 648.

- Glasgow, R.E.; Boles, S.M.; McKay, H.G.; Feil, E.G.; Barrera, M. The D-Net Diabetes Self-Management Program: Long-Term Implementation, Outcomes, and Generalization Results. Prev. Med. 2003, 36, 410–419.

- Swavely, D.; Vorderstrasse, A.; Maldonado, E.; Eid, S.; Etchason, J. Implementation and Evaluation of a Low Health Literacy and Culturally Sensitive Diabetes Education Program. J. Healthc. Qual. 2014, 36, 16–23.

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Lazo, M.; Peyrot, M.; Doswell, A.; Chang, Y.-T.; Hill, M.N.; Levine, D.; Wang, N.-Y.; Brancati, F.L. Effect of Problem-Solving-Based Diabetes Self-Management Training on Diabetes Control in a Low Income Patient Sample. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011, 26, 972–978.

- Carter, E.L.; Nunlee-Bland, G.; Callender, C. A Patient-Centric, Provider-Assisted Diabetes Telehealth Self-Management Intervention for Urban Minorities. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2011, 8, 1b.

- Osborn, C.Y.; Amico, K.R.; Cruz, N.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Kalichman, S.C.; O’Connell, A.A.; Wolf, S.A.; Fisher, J.D. Development and Implementation of a Culturally Tailored Diabetes Intervention in Primary Care. Transl. Behav. Med. 2011, 1, 468–479.

- Castejón, A.M.; Calderón, J.L.; Perez, A.; Millar, C.; McLaughlin-Middlekauff, J.; Sangasubana, N.; Alvarez, G.; Arce, L.; Hardigan, P.; Rabionet, S.E. A Community-Based Pilot Study of a Diabetes Pharmacist Intervention in Latinos: Impact on Weight and Hemoglobin A1c. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2014, 24, 48–60.

- Calderón, J.L.; Shaheen, M.; Hays, R.D.; Fleming, E.S.; Norris, K.C.; Baker, R.S. Improving Diabetes Health Literacy by Animation. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 361–372.

- Koonce, T.Y.; Giuse, N.B.; Kusnoor, S.V.; Hurley, S.; Ye, F. A Personalized Approach to Deliver Health Care Information to Diabetic Patients in Community Care Clinics. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 123–130.

- Kim, M.T.; Kim, K.B.; Huh, B.; Nguyen, T.; Han, H.-R.; Bone, L.R.; Levine, D. The Effect of a Community-Based Self-Help Intervention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 49, 726–737.

- Lee, M.-K.; Lee, K.-H.; Yoo, S.-H.; Park, C.-Y. Impact of Initial Active Engagement in Self-Monitoring with a Telemonitoring Device on Glycemic Control among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3866.

- Glasgow, R.E.; Nutting, P.A.; Toobert, D.J.; King, D.K.; Strycker, L.A.; Jex, M.; O’Neill, C.; Whitesides, H.; Merenich, J. Effects of a Brief Computer-Assisted Diabetes Self-Management Intervention on Dietary, Biological and Quality-of-Life Outcomes. Chonic Illn. 2006, 2, 27–38.

- Lujan, J.; Ostwald, S.K.; Ortiz, M. Promotora Diabetes Intervention for Mexican Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2007, 33, 660–670.

- Hill-Briggs, F.; Renosky, R.; Lazo, M.; Bone, L.; Hill, M.; Levine, D.; Brancati, F.L.; Peyrot, M. Development and Pilot Evaluation of Literacy-Adapted Diabetes and CVD Education in Urban, Diabetic African Americans. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008, 23, 1491–1494.

- Wallace, A.S.; Seligman, H.K.; Davis, T.C.; Schillinger, D.; Arnold, C.L.; Bryant-Shilliday, B.; Freburger, J.K.; DeWalt, D.A. Literacy-Appropriate Educational Materials and Brief Counseling Improve Diabetes Self-Management. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 328–333.

- White, R.O.; Chakkalakal, R.J.; Wallston, K.A.; Wolff, K.; Gregory, B.; Davis, D.; Schlundt, D.; Trochez, K.M.; Barto, S.; Harris, L.A.; et al. The Partnership to Improve Diabetes Education Trial: A Cluster Randomized Trial Addressing Health Communication in Diabetes Care. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 1052–1059.

- Mardani Hamuleh, M.; Shahraki Vahed, A.; Piri, A.R. Effects of Education Based on Health Belief Model on Dietary Adherence in Diabetic Patients. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2010, 9, 15.

- Taghdisi, M.; Borhani, M.; Solhi, M.; Afkari, M.; Hosseini, F. The Effect of an Education Program Utilising PRECEDE Model on the Quality of Life in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Health Educ. J. 2012, 71, 229–238.

- Rasoul, A.M.; Jalali, R.; Abdi, A.; Salari, N.; Rahimi, M.; Mohammadi, M. The Effect of Self-Management Education through Weblogs on the Quality of Life of Diabetic Patients. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 205.

- Song, M.-S.; Kim, H.-S. Intensive Management Program to Improve Glycosylated Hemoglobin Levels and Adherence to Diet in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2009, 22, 42–47.

- Kim, S.H.; Utz, S. Effectiveness of a Social Media–Based, Health Literacy–Sensitive Diabetes Self-Management Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2019, 51, 661–669.

- McGowan, P.; Lynch, S.; Hensen, F. The Role and Effectiveness of Telephone Peer Coaching for Adult Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Can. J. Diabetes 2019, 43, 399–405.

- Sims Gould, J.; Tong, C.; Ly, J.; Vazirian, S.; Windt, A.; Khan, K. Process Evaluation of Team-Based Care in People Aged >65 Years with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029965.

- Protheroe, J.; Rathod, T.; Bartlam, B.; Rowlands, G.; Richardson, G.; Reeves, D. The Feasibility of Health Trainer Improved Patient Self-Management in Patients with Low Health Literacy and Poorly Controlled Diabetes: A Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 1–11.

- Bartlam, B.; Rathod, T.; Rowlands, G.; Protheroe, J. Lay Health Trainers Supporting Self-Management amongst Those with Low Heath Literacy and Diabetes: Lessons from a Mixed Methods Pilot, Feasibility Study. J. Diabetes Res. 2016, 2016, 1–10.

- Petkova, V.B.; Petrova, G.I. Pilot Project for Education of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes by Pharmacists. Acta Diabetol. 2006, 43, 37–42.

- Wan, E.Y.F.; Fung, C.S.C.; Wong, C.K.H.; Choi, E.P.H.; Jiao, F.F.; Chan, A.K.C.; Chan, K.H.Y.; Lam, C.L.K. Effectiveness of a Multidisciplinary Risk Assessment and Management Programme—Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM) on Patient-Reported Outcomes. Endocrine 2017, 55, 416–426.

- Ichiki, Y.; Kobayashi, D.; Kubota, T.; Ozono, S.; Murakami, A.; Yamakawa, Y.; Zeki, K.; Shimazoe, T. Effect of Patient Education for Diabetic Outpatients by a Hospital Pharmacist: A Retrospective Study. Yakugaku Zasshi 2016, 136, 1667–1674.

- Siaw, M.Y.L.; Ko, Y.; Malone, D.C.; Tsou, K.Y.K.; Lew, Y.-J.; Foo, D.; Tan, E.; Chan, S.C.; Chia, A.; Sinaram, S.S.; et al. Impact of Pharmacist-Involved Collaborative Care on the Clinical, Humanistic and Cost Outcomes of High-Risk Patients with Type 2 Diabetes (IMPACT): A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 475–482.

- Hernández-Jiménez, S.; García-Ulloa, A.C.; Bello-Chavolla, O.Y.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Kershenobich-Stalnikowitz, D. Long-Term Effectiveness of a Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Care Program. The CAIPaDi Model. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 151, 128–137.

- Hung, J.-Y.; Chen, P.-F.; Livneh, H.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Guo, H.-R.; Tsai, T.-Y. Long-Term Effectiveness of the Diabetes Conversation Map Program. Medicine 2017, 96, e7912.

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26.

- Abraham, C.; Sheeran, P. The Health Belief Model. In Cambridge Handbook of Psychology, Health and Medicine; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 97–102.

- Trento, M.; Passera, P.; Borgo, E.; Tomalino, M.; Bajardi, M.; Brescianini, A.; Tomelini, M.; Giuliano, S.; Cavallo, F.; Miselli, V.; et al. A 3-Year Prospective Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Group Care in Type 1 Diabetes. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2005, 15, 293–301.

- Vaux, A. Social Support: Theory, Research, and Intervention; Praeger Publishers: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998.

- D’Zurilla, T.J.; Nezu, A.M. Development and Preliminary Evaluation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1990, 2, 156–163.

- Lusk, S.L. Health Promotion Planning: An Educational and Environmental Approach. Patient Educ. Couns. 1992, 19, 298.

- Fisher, W.A.; Fisher, J.D.; Harman, J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A General Social Psychological Approach to Understanding and Promoting Health Behavior. In Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness; Blackwell Publishing Ltd: Malden, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 82–106.

- Fransen, J.; Pion, J.; Vandendriessche, J.; Vandorpe, B.; Vaeyens, R.; Lenoir, M.; Philippaerts, R.M. Differences in Physical Fitness and Gross Motor Coordination in Boys Aged 6–12 Years Specializing in One versus Sampling More than One Sport. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 30, 379–386.

- Stewart, M. Towards a Global Definition of Patient Centred Care. BMJ 2001, 322, 444–445.

- Lindblad, S.; Ernestam, S.; Van Citters, A.D.; Lind, C.; Morgan, T.S.; Nelson, E.C. Creating a Culture of Health: Evolving Healthcare Systems and Patient Engagement. QJM Int. J. Med. 2017, 110, 125–129.

- Freeman, K.; Hanlon, M.; Denslow, S.; Hooper, V. Patient Engagement in Type 2 Diabetes: A Collaborative Community Health Initiative. Diabetes Educ. 2018, 44, 395–404.

- Pinheiro, P. Future Avenues for Health Literacy: Learning from Literacy and Literacy Learning. In International Handbook of Health Literacy. Research, Practice and Policy across the Lifespan; Okan, O., Bauer, U., Levin-Zamir, D., Pinheiro, P., Sørensen, K., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 555–572.

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Eisenstat, S.A.; Barnard, L.S.; Wexler, D.J. Multidisciplinary Coordinated Care for Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Analysis of Patient Perspectives. Prim. Care Diabetes 2018, 12, 218–223.

- Pascucci, D.; Sassano, M.; Nurchis, M.C.; Cicconi, M.; Acampora, A.; Park, D.; Morano, C.; Damiani, G. Impact of Interprofessional Collaboration on Chronic Disease Management: Findings from a Systematic Review of Clinical Trial and Meta-Analysis. Health Policy 2021, 125, 191–202.

- Tanaka, H.; Medeiros, G.; Giglio, A. Multidisciplinary Teams: Perceptions of Professionals and Oncological Patients. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2020, 66, 419–423.

- D’amour, D.; Oandasan, I. Interprofessionality as the Field of Interprofessional Practice and Interprofessional Education: An Emerging Concept. J. Interprof. Care 2005, 19 (Suppl. 1), 8–20.

- Bodenheimer, T.; Sinsky, C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient Requires Care of the Provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 573–576.

- Rothman, R.L. Influence of Patient Literacy on the Effectiveness of a Primary Care–Based Diabetes Disease Management Program. JAMA 2004, 292, 1711.

- Hunt, C.W. Technology and Diabetes Self-Management: An Integrative Review. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 225.

- Thornton, J. Clinicians Are Leading Service Reconfiguration to Cope with Covid-19. BMJ 2020, 369, m1444.

- Jaly, I.; Iyengar, K.; Bahl, S.; Hughes, T.; Vaishya, R. Redefining Diabetic Foot Disease Management Service during COVID-19 Pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 833–838.

- Chrvala, C.A.; Sherr, D.; Lipman, R.D. Diabetes Self-Management Education for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review of the Effect on Glycemic Control. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 926–943.

- Renwick, K.; Powell, L.J. Focusing on the Literacy in Food Literacy: Practice, Community, and Food Sovereignty. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2019, 111, 24–30.