Robert of Anjou King of Sicily (1309–1343). Robert of Anjou was the third king of the Angevin dynasty on the throne of Sicily. He ruled from 1309 to 1343, but, in these years, Sicily was under the domain of the Aragonese dynasty and, hence, his authority was limited to the continental land of the Kingdom and his court was mainly focused in the city of Naples. From an iconographic point of view, he is particularly interesting because, between his official representations (namely, commissioned directly by him or his entourage), he was the first king of Sicily who made use not only of stereotyped images of himself, but also of physiognomic portraits. In particular, this entry focuses on these latter items, comprising the following four artworks: Simone Martini’s altarpiece, the Master of Giovanni Barrile’s panel, the Master of the Franciscan tempera’s canvas, and the so-called Lello da Orvieto’s fresco.

1. Introduction

Robert of Anjou was the third exponent of the Angevin dynasty on the throne of Sicily. He was crowned on 3 August 1309, and he ruled until his death on 20 January 1343. In reality, in these years, Sicily was under the domain of the Aragonese dynasty and, hence, his authority was limited to the continental land of the Kingdom and his court was mainly focused in the city of Naples. He also held the title of King of Jerusalem and Count of Provence, Forcalquier, and Piedmont and, during some periods, he was also proclaimed Lord of some cities of central and northern Italy, as well as Senator of Rome and Papal Vicar in the Italian territories of the Empire (in general, regarding Robert of Anjou, see

[1] and, in more synthesis,

[2],

[3] (pp. 183–249), and

[4]). Among his contemporaries, Robert had a reputation as an intellectual and he was frequently celebrated for his erudition and wisdom (he was often compared to the biblical Solomon; see

[5]), as well as for his marked religiosity (he was himself author of numerous sermons and two theological treatises; see

[6]). In particular, the Angevin was an active patron in both the scientific-literary and artistic fields, and, exactly in this last sector, historians have highlighted an intense activity in the commission of his own portraits for political and propagandistic purposes (in this regard, see lastly, but with references to the previous bibliography,

[7][8]. On Robert of Anjou’s portraits, we also point out

[9]. Instead, regarding the propagandistic activity of Robert of Anjou in general,

[10] is worthy of reporting).

From an iconographic point of view, Robert of Anjou is particularly interesting because he was the first king of Sicily who made use, between his official representations (namely, commissioned directly by him or his entourage), not only of stereotyped images of himself, but also of physiognomic portraits. In the first group are representations connected with public employments and representing Robert in his institutional role of King (indeed, he is depicted while seated on a throne bearing a crown, sceptre, and globe). They are the royal images on bulls and seals; the representations of the monarch on the coins minted in the Kingdom of Sicily, in central and northern Italy, and in Provence; and the statue sculpted by Tino da Camaino in approximately 1325 for the sarcophagus of Mary of Hungary in the presbytery of the Church of Santa Maria Donnaregina in Naples (despite this image being placed in a religious context and having limited visibility, it represented Robert in his institutional role and, indeed, he had been carved in majesty).

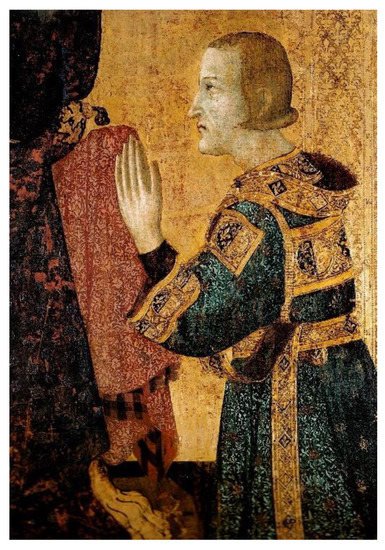

In the second group, instead, are representations connected with religious and devotional contexts and associated, so to speak, with the private sphere and the personal practices of Robert. They represent the Angevin as a devotee (face in profile, kneeling position, small size, and proximity to religious subjects) while he carries out liturgical activities and devotional acts. What is more, they render, following the report on the bones of the King by the Istituto di Anatomia Umana Normale dell’Università di Napoli in June 1959 (see

[11] (pp. 40–42)), his real physical features: light brown hair that falls straight down to the neck and concludes with a rather tight curl; shaved, thin, and oblong face; protruding and pointed chin; accentuated jaw; thin lips; pronounced nose; narrow eyes that, as well as the cheeks, are rather sunken and that highlight the cheekbones; high and spacious forehead; and deep wrinkles around the nose and mouth (

Figure 1). This entry focuses on this second group of images. In particular, they are the following four artworks: Simone Martini’s altarpiece, the Master of Giovanni Barrile’s panel, the Master of the Franciscan tempera’s canvas, and the so-called Lello da Orvieto’s fresco (regarding the identification of Robert of Anjou’s official image, see

[12] (pp. 97–110), with more information and bibliographic references).

Figure 1. Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse crowning King Robert of Anjou, painting on wood, 1317–1319. Naples, Museo di Capodimonte. Detail of Robert’s face. Source: public domain image.

2. Simone Martini’s Altarpiece

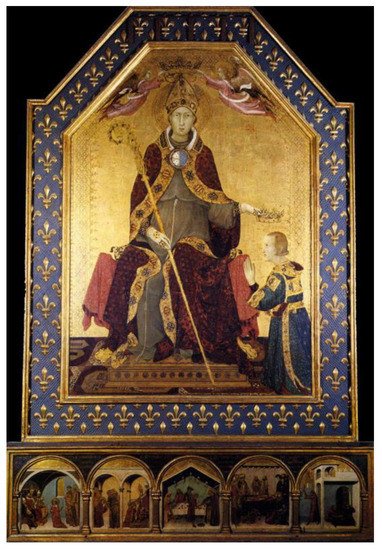

This altarpiece, painted on wood and now in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, represents Saint Louis of Toulouse crowning his younger brother, King Robert of Anjou (

Figure 2) (regarding this image, see:

[13][14][15][16][17],

[18] (pp. 136–154),

[19][20][21][22][23][24],

[25] (pp. 133–147)). The Sienese painter Simone Martini (who directly signed the artwork with the inscription «SIMON DE SENIS ME PINXIT») painted this altarpiece indicatively between the summer of 1317 and 1319 (namely, in the years immediately following the canonisation of the Saint). The panel has a main body of 250 × 188 cm and a predella of 56 × 205 cm, but Julian Gardner has hypothesised that, originally, it also had lateral small columns and, at the top, a pinnacle with the image of a blessing Christ

[13]. The main scene is enclosed in a blue band decorated with lily flowers and, at the top, a five-pointed red label (allusion to the heraldic symbol of Robert himself). Moreover, it has a golden background edged with a weave of lilies. The panel represents Saint Louis of Toulouse seated on a throne while two angels are crowning him and, in turn, he is crowning his younger brother. Robert is devoutly kneeling at his feet and he wears ceremonial robes and a sort of pallium, both richly decorated and embroidered with the coats of arms of Anjou and Jerusalem. If the face of Louis, in the frontal position, is rather stereotyped, the face of Robert, in profile position, is considered one of the first examples of a portrait in medieval art and, as said, it follows the real appearance of the King. Precious gems and goldsmith works directly embedded in the wooden panel decorate the whole composition. In the underlying predella, there are five episodes of Louis’ life taken from the texts of his canonisation process. From left to right, they are as follows: the election as bishop by Pope Boniface VIII; the taking of the Franciscan habit and the consequent acceptance of the bishopric of Toulouse; Louis in the act of serving at the table; Louis’ death; and his post-mortem miracle (regarding the scenes in the predella, see

[19]).

Figure 2. Simone Martini, Saint Louis of Toulouse crowning King Robert of Anjou, painting on wood, 1317–1319. Naples, Museo di Capodimonte. Source: public domain image.

Considering the presence of the regal image and the Angevin heraldic symbols, it seems plausible that the patron of this artwork was a member of the royal court. In particular, thinking about Simone Martini’s attention to rendering Robert’s aspect, it seems unlikely that the King did not play a preponderant role in its commission. Evidently, it was him, assisted by some members of his entourage, who ordered the altarpiece. Regarding the original place of collocation of this panel, we can presume that it was on the altar of one of the chapels of the south side of the transept of the church of the Convent of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples (regarding this building and its internal decoration, see:

[26] (pp. 46–75),

[27][28][29][30][31]). This means that the panel was intended for the presbytery of the church and, therefore, for a purely religious context, particularly connected with liturgical celebrations. Hence, its visibility was probably rather limited and, in practice, restricted only to the religious members of the aforementioned church. Indeed, the laity could not generally access the presbytery and, usually, a choir and a rood screen separated the aisles of the churches from this area. This leads one to reconsider the meaning and function of this image. Generally, historians and art historians have ascribed to the main scene not only the celebratory intent of Saint Louis, who renounces the crown of the temporal power for that of spiritual power, but also a political and propagandistic message in favour of Robert. Indeed, the coronation by the newly canonised Saint legitimised his authority of the throne of the Kingdom of Sicily, thanks to both the renunciation to the succession of the elder brother (which really occurred in 1296) and the sacrality that Louis spread across the whole Angevin dynasty (the so-called beata stirps), that also enriched Robert’s succession with divine favour. This message was particularly functional to the Angevin policy. Indeed, during this time, he defended himself from the dynastic claims of Charles Robert, King of Hungary (son of the elder brother of Louis and Robert, Charles Martel), and from oppositions of the Ghibellines of central and northern Italian city states.

If we consider that the image was likely placed in an ecclesiastic space and connected to liturgic activities, and that it had limited visibility, it seems hardly credible that it played a political function. In reality, a religious and devotional interpretation is more plausible. In particular, it seems appropriate to relate this artwork to the role of Protector of the Angevin dynasty and Intercessor near God for the soul of its members attributed to Saint Louis. In this sense, we can suppose that the scene represented the Saint precisely in his function of intermediary, namely, in the act of delivering to Robert, after the accomplished intercession, the coveted crown of the Kingdom of Heaven. In other words, the image visually foreshadowed, to the friars of the Convent of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples, Robert of Anjou achieving eternal life, probably thanks to the prayers that the same friars performed in front of the altar where the panel was placed (for more details and bibliographic references about this interpretation, see

[12] (pp. 111–130)).

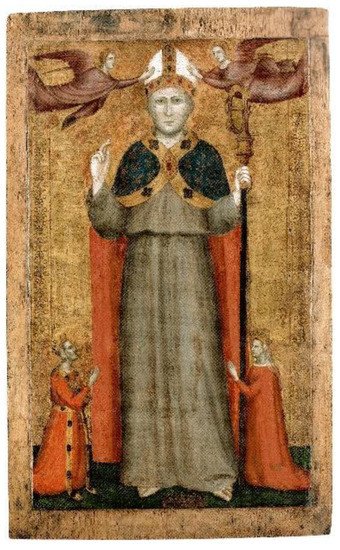

3. The Master of Giovanni Barrile’s Panel

This painted wooden panel, now at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence (inventory number 821.1.14), again represents Saint Louis of Toulouse with, at his feet, Robert of Anjou and his wife Sancia of Majorca in an act of devotion (

Figure 3) (regarding this image, see:

[32] (pp. 211–213),

[33] (card no. 41, p. 297),

[34] (p. 212),

[35] (p. 109, note 3),

[36] (card no. 23, pp. 184–187)). It has been attributed to a Neapolitan painter conventionally defined as the Master of Giovanni Barrile and it has been hypothetically dated to the 1330s, but no later than 1336. This work has smaller dimensions in comparison to the previous one (height, 64.3 cm; width, 40 cm; depth, 1.5 cm) and it is characterised by a greater decorative simplicity. The scene depicts, on a golden background, the Saint in a blessing act and in an upright position while he is receiving the mitre from two flying angels. At his feet, there is a crown that symbolises his renunciation to any temporal authority due to his religious vocation. At his side, finally, there are the two Angevin rulers. They have small dimensions and they are in profile position and in the act of addressing their prayers towards the Saint. Both are wearing rather simple red tunics, but they are distinguished by the crown, and Robert, moreover, also flaunts a sort of golden pallium embroidered with medallions decorated with lily flowers. The King’s face has the aforementioned physiognomic features.

Figure 3. Master of Giovanni Barrile,

Saint Louis of Toulouse worshipped by Robert of Anjou and Sancia of Majorca, painting on wooden panel, 1330–1336. Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet. Image published in

[12] (Figure 11).

Considering the presence of Robert and Sancia, the commission of the panel has been attributed to the royal couple, while it seems plausible that, originally, it was intended for Saint Louis’ tomb and chapel in the presbytery (probably near the main altar) of the church of the Convent of the Minors in Marseille (regarding the evidence related to the translation of Saint Louis’ remains in this church, see

[37]). Hence, presumably, its visibility was limited and restricted to the members of this convent. For this reason, although it has been pointed out that the scene supports the legitimacy of Robert’s power and illustrates the propensity for holiness of the Angevins

[34] (p. 212), it seems more convincing that it had a religious and devotional function. What is more, from an iconographic point of view, the panel did not explicitly stage the alleged passage of power from Louis to Robert. Here, indeed, Louis’ crowning or blessing of Robert and his authority are lacking. On the contrary, in the scene, the first does not interact in any way with the second. More likely, the artifact displayed in visual form the cult that, from their Neapolitan court, Robert and Sancia practiced towards the Saint buried in Marseille and it probably stimulated the prayers of the friars of the convent towards the Saint in favour of the royal couple. In this sense, the panel played a role in the religious and liturgical activities of the church (for more details and bibliographic references about this interpretation, see

[12] (pp. 130–136)).

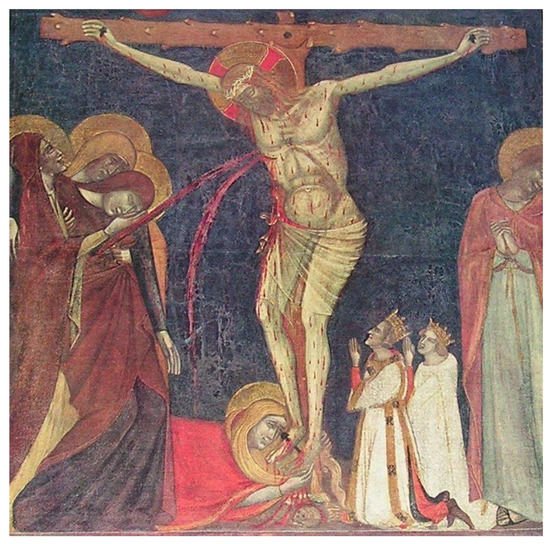

4. The Master of the Franciscan Tempera’s Canvas

This tempera on canvas, now in a private collection, represents—in a rather pathetic and intense way—a crucifixion (

Figure 4) (regarding this image, see:

[32] (pp. 235–237 and p. 257),

[38] (pp. 88–89 and pp. 409–413),

[39] (p. 48),

[40],

[35] (p. 149 and p. 166, note 81),

[41] (p. 73, p. 78, and p. 80)). It has been attributed to a southern artist active in Naples conventionally defined as Master of the Franciscan tempera, and it has been hypothetically dated to the 1330s, but no later than 1336. This work has rather large dimensions (130 × 135 cm, and note that it has been cropped in the margins) and it was part of a wider series of which only three other canvases remain:

Madonna with Child between Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint Clare of Assisi,

Stigmata of Saint Francis of Assisi, and

Flagellation. The scene represents, on a dark blue background, Christ nailed to the cross with Saint John the Evangelist, Saint Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin, presumably sustained by Mary (mother of James the Less and Joseph) and Salome (the references are to Mt 27,55–56 and Mc 15,40–41), around him. Kneeling at the foot of the cross are Robert of Anjou and Sancia of Majorca. They are much smaller than the other figures and are depicted in profile position and in an act of prayer. Robert is wearing a red tunic and a white ceremonial robe quilted ton sur ton with small lily flowers. He is bearing the usual lily crown and golden pallium embroidered with medallions decorated with lily flowers. The King’s face has the aforementioned physiognomic features.

Figure 4. Master of the Franciscan tempera,

Crucified Christ worshipped by Robert of Anjou and Sancia of Majorca, tempera on canvas, 1331–1336. Private collection. Image published in

[12] (Figure 13).

Considering the presence of Robert and Sancia, the commission of the panel has been attributed to the royal couple, while it seems plausible that, originally, it was intended for the female section of the Monastery of Santa Chiara in Naples (in general, regarding this building, see in summary:

[42][43],

[26] (pp. 132–153),

[44]. Instead, for a more recent study of some specific aspects of this monastery, see

[45]). More exactly, Adrian Hoch has pointed out that these canvases, due to their mobile nature, had the function of a sort of portable series of frescoes. In other words, they were displayed when necessary (for instance, during specific festive celebrations) as an alternative to the mural decoration and, after that, removed. Thanks to their flexibility, these artifacts were particularly suitable for supporting religious persons during liturgical ceremonies and they were staged during real ritual performances

[40] (p. 224). For this reason, it seems plausible that they were used, depending on the needs, in the various spaces of the cloistered area of the monastery. This means that their visibility was rather restricted and, all in all, limited almost exclusively to the nuns of the aforementioned building. Hence, we can conclude that these canvases had a liturgical function and helped the nuns in their prayers. In other words, they stimulated, through the visual act, their meditations on some of the fundamental moments of religious worship. In this context, Robert and Sancia’s images presumably had the aim of making materially visible to the Poor Clares the devotion and religiosity of the royal couple and, maybe, of inspiring their prayers in favour of the souls of the two founders of the Monastery of Santa Chiara. In this sense, this portrait of Robert also had a devotional and liturgical function (for more details and bibliographic references about this interpretation, see again

[12] (pp. 136–144)).

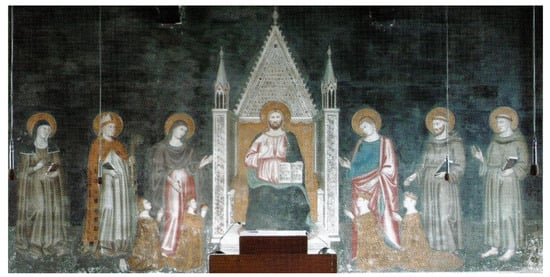

5. The So-Called Lello da Orvieto’s Fresco

This fresco, placed in the former male chapter house (now oratory of the Poor Clares of the Church of Cristo Redentore e San Ludovico d’Angiò) of the Monastery of Santa Chiara in Naples, represents Christ enthroned between saints and Angevin royals (

Figure 5) (regarding this image, see:

[32] (pp. 131–132),

[38] (pp. 268–269),

[39] (p. 37),

[46][47]). The work has been attributed to the so-called Lello da Orvieto (regarding this painter, see

[48]), but the existence of an artist of this name has been disputed and even its attribution has recently been questioned (regarding this, see:

[39] (p. 37),

[47] (p. 402, note 36)). Regarding the dating, it is plausible that it was created between 1336 and 1337. The fresco has monumental dimensions (it is 983 cm long and 840 cm high) and entirely covers the south wall of the hall. The scene depicts Christ seated in majesty (in the centre) with six saints at his side, who are interceding near Him. In particular, they are the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, accompanied by the most significant members of the Franciscan Order: on one side, there is Saint Louis of Toulouse and Saint Clare of Assisi; on the other side, there is Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Anthony of Padua. At their feet, in much smaller dimensions, depicted in profile position and demonstrating a prayerful attitude towards the figure of the Lord, there are four Angevin rulers. The first two are identifiable as Robert of Anjou and Sancia of Majorca, while the other two are their heirs to the throne, Johanna I of Anjou (on 4 November 1330, designated as Robert’s successor and, for this reason, depicted bearing a crown on her head) and her husband Andrew of Hungary. Robert, as usual, is wearing a golden ceremonial robe dotted with lily flowers and a sort of pallium and bearing a lily crown. The King’s face has the aforementioned physiognomic features, although he is rendered in a slightly different and more idealised way. At the least, his appearance seems more youthful, although the fresco dates after the previous images (but, maybe it suffered some remaking).

Figure 5. The so-called Lello da Orvieto,

Christ enthroned between saints and Angevin royals, fresco, 1336–1337. Naples, Monastery of Santa Chiara, former male chapter house. Image published in:

[12] (Figure 16).

Regarding the commission of this artwork, it is plausible that the same Angevin royals ordered it (in particular, Robert or Sancia, who were most involved with the foundation of the Monastery of Santa Chiara). Regarding visibility, it is worth noting that the chapter house was the hall where, generally, the friars of the monastery gathered themselves in assemblies in order to enact provisions and deal with affairs concerning the life of the monastic community. Moreover, this place hosted the celebration of the provincial and general chapters of the Order and it was used as representative space at the time of receiving distinguished guests. Therefore, some persons who were not strictly part of the aforementioned community occasionally experienced admission to this hall, but we should consider that, almost exclusively, only members of the Franciscan Order accessed it and, in particular, only the friars of the Monastery of Santa Chiara regularly attended this hall. Hence, the visibility of the fresco, despite its monumental dimensions, was rather limited and restricted to a reduced group of religious persons. For this reason, we can hypothesise that the painting did not play a political or propagandistic role, but instead had a more religious and liturgical function. In particular, the fresco likely did not aim to celebrate the Angevin royals and it did not stage the divine consent to their authority, but instead displayed to the friars of Santa Chiara the devotion and religiosity of the Angevin rulers and it reminded them of one of the main tasks that, as well as the Poor Clares, they had in the monastery: to pray to Christ in favour of the members of the Angevin dynasty in order to obtain (thanks also to the intercession of the saints depicted in the fresco) forgiveness for their sins and the achievement of eternal salvation for their souls (for more details and bibliographic references about this interpretation, see again

[12] (pp. 145–152)).

6. Conclusions

In order to summarise the general lines of Robert of Anjou’s physiognomic portraits, we can conclude that they were adopted in paintings on wooden panels, canvases, and wall frescoes with, in general, rather monumental dimensions and good attention to the iconographic details. They were placed, in particular, in the city of Naples and in the internal parts of religious buildings, such as the transept of the church of the Convent of San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples, the female cloistered area and the male chapter house of the Monastery of Santa Chiara in Naples, and the presbytery of the church of the Convent of the Minors in Marseille. Hence, their visibility was, above all, limited to the religious members of these institutions. Moreover, Robert of Anjou was always depicted with the traditional iconographic features of a devotee: face in profile, kneeling position, small size, and proximity to religious subjects (in particular, Saint Louis of Toulouse, but also Christ). Finally, the King’s face was not rendered in an idealised way, but following his real appearance. In consideration of these characteristics, these portraits do not seem to be part of a specific political strategy of staging of the visual representation of the royal face for government purposes or with the aims of legitimising and strengthening the monarchical power. On the contrary, they seem to have been used for purposes characterised by liturgical and devotional intentions.

This leads one to reconsider some historiographical interpretations that propose the Angevin as actively engaged in the making, through his artistic commissions, of a “self-constructed image”

[49] (p. 77) in order to be physically present and immediately identifiable to his subjects, and as involved in the use of his “self-presentation as political instrument”

[8] in order to strengthen his authority. In summary, that he adopted a “real and actual ‘iconographic propaganda’”

[50] (pp. 67–68). In reality, the reasons for the adoption of the Robert of Anjou’s portraits should be attributed to the private/individual sphere and to religious devotion, not to the public field or to political celebration and administration. It seems plausible that his naturalistic portraits did not aim to express any specific symbolic and ideological message, but only to represent him in the guise of a simple man who, with the help of saints, invoked divine forgiveness of his sins and salvation for his soul. Certainly, the Medieval iconographic language could not completely disregard the assumption of some specific royal attributes in order to favour the identification of the subject (for instance, symbols of power such as the crown and ceremonial robes, designed to highlight his social role, and heraldic emblems that defined his dynastic membership). For this reason, he was also depicted with a crown and ceremonial robes and his portraits were dotted with lily flowers. However, despite this, Robert’s images with his real appearance presumably wanted to express the completely human and transitory nature of the King, who, far from any political intent or celebration of his monarchical function, offered devoutly and humbly (as a simple man or a private citizen) his prayers to God, hoping to achieve, also thanks to the prayers of the beholders of these representations, the forgiveness of his sins and the crown of eternal life in the Kingdom of Heaven.