Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Virology

The influenza virus neuraminidase (NA) is primarily involved in the release of progeny viruses from infected cells—a critical role for virus replication.

- neuraminidase

- antibodies

1. Introduction

Vaccination remains the most effective countermeasure against influenza virus-associated morbidity and mortality [1,2,3,4]. Current seasonal influenza vaccines target the immuno-dominant surface glycoprotein, the hemagglutinin (HA) (Figure 1A) [2,5,6], as HA is responsible for viral attachment to sialic acid receptors on the host cell and fusion of viral and host endosomal membranes [6,7]. However, HA has high plasticity and changes constantly due to polymerase error rate and immune selection pressure, defined as antigenic drift [8]. As a result of this, seasonal vaccine strains must be updated annually, and, occasionally a mismatch between vaccine strains and circulating strains can result in seasonal epidemics [9,10,11]. Despite the necessity for the rapid production of seasonal influenza virus vaccines, the current process is time-consuming and expensive [12]. Hence, the investigation of new viral targets for influenza virus vaccines that are broadly protective, and do not change as frequently as HA, is warranted.

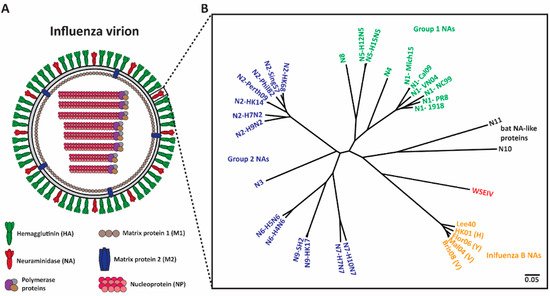

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of influenza NAs. (A) Depiction of an influenza virion. There are two major surface influenza glycoproteins: the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). (B) Phylogenetic tree of NA subtypes. Influenza A NAs comprise Group 1 (N1, N4, N5, and N8), Group 2 (N2, N3, N6, N7, and N9) and bat-like (N10 and N11) NAs. Influenza B NAs consist of Yamagata-like, Victoria-like and Hong Kong-like lineages. Wuhan spiny eel influenza virus (WSEIV) NA, a close relative of influenza B NAs, is also included in the phylogenetic tree. The scale bar represents a 5% change in amino acids. The phylogenetic tree was built using amino acids in Clustal Omega and then visualized in FigTree.

Neuraminidase (NA) (Figure 1A), the second surface glycoprotein of influenza virus, is a tetrameric type II transmembrane protein that plays several important roles in the viral replication cycle due to its enzymatic activity [13,14]. Initially, when an influenza virion enters a host, the virion needs to penetrate heavily glycosylated mucosal barriers [13,15,16]. These barriers act as decoy receptors for HA binding and neutralize the virion [13,17]. Here, NA assists the virion by releasing the virus particles from the decoy receptors, thus penetrating the mucus layer and gaining access to the underlying respiratory epithelium [13,15,16,17]. Upon entering and successfully replicating in the host cell, NA is crucial for viral detachment from the host cell by cleaving off sialic acid receptors that have adhered to HA [13,18,19]. Additionally, influenza virions are also known to adhere to each other via interactions between HA and sialic acids on glycans of other HAs, and between HA and other glycoproteins in the mucus layer [14,18]. NA prevents this aggregation and allows for the efficient spread of newly produced virions in the host and the subsequent transmission between hosts [14,20]. Interestingly, NA also plays a critical role in virus infectivity and HA-mediated membrane fusion [21].

Shifting the immune response towards the second major glycoprotein, NA, is a promising option for the improvement of seasonal vaccines. NA has a slower rate of antigenic drift, has fewer subtypes (Figure 1B), and lower immune selective pressure [22,23,24]. Hence, NA is an attractive target and anti-NA antibodies can inhibit the enzymatic activity of the virus via direct binding or steric hinderance of the active site [25]. Additionally, animal studies indicate that the induction of an anti-NA antibody response can confer protection [26,27,28]. Human challenge studies performed in the early 1970s revealed that anti-NA antibody titers inversely correlated with virus shedding and disease symptoms [29,30]. Recent studies indicate that NA inhibition (NI) titers independently correlated with protection against influenza virus symptoms and resulted in decreased viral shedding [31,32,33,34]. Understanding the role of anti-NA antibodies in controlling influenza virus infection can be improved through the generation of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs). In this review, we summarize several studies that isolated and characterized anti-NA antibodies from humans, and we discuss how this information will provide supporting evidence for the inclusion of standardized amounts of NA in future vaccine preparations.

2. NA-Based Immunity

Antibody responses towards influenza virus antigens typically target the two major surface glycoproteins, HA and NA (Figure 1A) [35]. Despite the importance of both anti-HA and anti-NA antibodies in preventing and controlling influenza virus infection, HA usually exhibits immunodominance over NA following influenza vaccination [13,36,37]. On the other hand, natural influenza virus infection induces more balanced antibody responses towards HA and NA [37]. Natural infection results in high seroconversion rates against both HA and NA, as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) [38,39]. A study in H1N1 pandemic influenza virus-infected patients demonstrated that seroconversion to NA could be observed at day 7 and peaked at day 28. However, NA antibodies began to decline by day 90 [39]. In the case of N2 antibodies, one study reported that N2 antibodies began to decline to undetectable levels within 5 months following infection, while another study reported persistence of detectable N2 antibodies up to 4 years after infection [40,41]. It should be noted that, in general, N1 antibody titers are lower than N2 and influenza B NA antibodies [42]. The lower titers of N1 antibodies might be caused by the lower immunogenicity of N1 but could also be an artifact of the reagents used to measure these antibody titers [38,39,42].

Several different types of influenza virus vaccines are currently in use to help protect against influenza virus infections. Immunoglobin responses towards NA after vaccination are substantially reduced when compared to infection [37]. Even though there are several different vaccines against influenza virus, only a handful of the vaccines can induce an immune response against NA, and several of the licensed vaccines contain little to no (e.g., Flucelvax) antigenic NA [43]. Live-attenuated virus vaccines (LAIV), whole inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and some split virus vaccines can induce NA antibody responses of varying degrees [34,44,45,46,47]. Similar to infection, antibodies in humans that developed post-vaccination peaked at 2–3 weeks; however, they only persisted for one year [48,49,50,51]. Additionally, route of administration can also have an effect on the humoral response against NA [52,53]. Unlike antibody responses to natural infection, antibody responses to vaccination are short-lived, and antibody titers induced by vaccination may even decline within a given influenza season [44,54,55]. NA-specific human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that are induced by natural infection and vaccination will be further discussed in the upcoming sections.

1.2. Human mAbs That Target NA

HA and NA-specific antibodies utilize different modes of action to control influenza virus infection. Anti-HA mAbs predominantly bind to the globular head domain and inhibit virus attachment and entry into the host cell [56,57]. Thus, HA-specific mAbs have potent neutralizing activity [58]. Additionally, some HA head-specific mAbs facilitate Fc receptor-mediated cytotoxicity, such as antibody dependent cellular toxicity (ADCC) [59,60]. Several studies have described human mAbs that are directed against the receptor binding site of HA, which have neutralizing activity and are broadly protective in mice [61,62,63,64]. In contrast to the head-specific mAbs, mAbs that bind to HA stalk inhibit viral-endosomal fusion [65]. Although the titers of stalk binding mAbs in humans are typically low, they bind to HA from different subtypes and have much broader neutralizing capacity and increased Fc-FcR activity when compared to mAbs targeting the head domain [5,65,66,67,68,69]. Different to anti-HA mAbs, anti-NA mAbs play a major role at the later stages of viral replication, specifically when the influenza virion buds off from the infected cells [18]. During the final stages of viral replication, NA enzymatically cleaves off sialic acid residues on the host cell surface, releasing virus progeny [18,19]. It is at this point that most of the anti-NA mAbs inhibit viral egress [13,70]. Since NA mAbs are mostly effective during viral egress, virus titer is not generally affected during infection in an in vitro plaque reduction assay [71,72,73,74]. However, the plaque diameter is significantly reduced in the presence of anti-NA mAbs [72,73,74]. Therefore, most of the mAbs against NA are non-neutralizing but are still able to inhibit the enzymatic activity of NA and prevent virion release and spread from the host cell [25]. Furthermore, some NA-specific mAbs also mediate ADCC, which in turn activates natural killer (NK) cells [20,75,76,77]. Upon activation via effector cells (e.g., NK cells, macrophages), they can produce the antiviral cytokine IFN-γ and degranulate or phagocytose infected cells, aiding in the clearance of virus-infected cells [60,77,78,79]

Influenza virus vaccination and natural infection have the ability to induce a broad immune response against NA glycoprotein. This is demonstrated by the isolation of several human mAbs after both vaccination and natural infection. Even though some of the isolated human mAbs have a narrow reactivity, several of the isolated human mAbs have very broad reactivity spanning across both influenza A and influenza B strains (Figure 2 and Table 1). Below we describe human NA mAbs that have been isolated and their exciting reactivity.

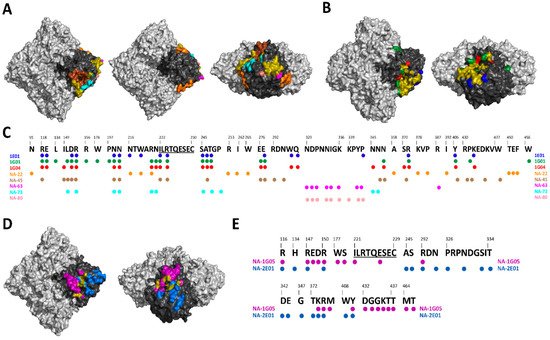

Figure 2. Mapping of NA-specific human monoclonal mAbs with known epitopes. (A) Top, bottom and side views of the A/Hunan/02650/2016 N9 (PDB ID: 6Q1Z) showing the epitopes of NA-22 in orange, NA-45 in brown, NA-63 in pink, NA-73 in teal, and NA-80 in salmon. (B) Top and side views of the A/California/04/2009 N1 (PDB ID: 6Q23) showing the epitopes of 1E01 in blue, 1G01 in green, and 1G04 in red. (C) Alignment of A/Hunan/02650/2016 N9 with the epitopes of 1E01, 1G01, 1G04, NA-22, NA-45, NA-63, NA-73, and NA-80. Universally conserved sequence “ILRTQESEC” is underlined. (D) Top and side views of the B/Perth/211/2001 NA (PDB ID: 3K38) showing the epitopes of NA-1G05 in purple and NA-2E01 in light blue. (E) Alignment of B/Perth/211/2001 with the epitopes of NA-1G05 and NA-2E01. Universally conserved sequence “ILRTQESEC” is underlined. For A, B and D overlapping epitopes between at least two mAbs are show in olive. Light gray denotes the NA tetramer, with the monomer highlighted in black.

Table 1. Summary of NA mAbs isolated from humans.

| Reactivity | Ref. | mAb Name | Induced after |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 NA | [37] | 1000-3C05, 1000-2E06, 1000-3B04, 1000-3B06, EM-2E01, 1000-1D05, 1000-1E02, 1000-1H01, 294-G-1F01, 294-A-1C02, 295-G-2F04, 300-G-2A04, 300-G-2F04, 294-A-1C06 | H1N1 infection |

| [80] | AG7C, AF9C | Seasonal trivalent inactivated vaccine | |

| Group 2 NA | [37] | 229-1D05, 235-1C02, 235-1E06, 294-1A02, 228-1B03, 228-3F04, 2291B05, 229-1F06, 229-1G03, 229-2B04, 229-2C06, 229-2E02 | H3N2 infection |

| [70,81,82] | NA-97 | A/British Columbia/1/2015 (H7N9) natural infection | |

| [70,81,82] | NA-22, NA-45, NA-63, NA-73, NA-80 | A/Shanghai/2/2013 (H7N9) monovalent inactivated influenza vaccine | |

| Influenza B NA | [83] | NA-1A03, NA-1G05, NA-2D10, NA-2E01, NA-2H09, NA-3C01 | Influenza B infection |

| [84] | 1086C12, 1092D4, 1092E10, 1122C7 | Quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine | |

| Pan NA | 1G01, 1E01, 1G04 | H3N2 infection |

3. NA Human mAbs Inform Vaccine Design

The development of NA vaccine antigens is complicated by several factors. The skewed antibody response towards HA is mainly due the presence of approximately four times more HA than the NA on the influenza virion surface [87]. As a result of the immunodominance of HA over NA, HAs evolve more quickly than NAs. A H3N2 virus study showed that the globular domain of HA evolves at a rate of 12.9 × 10−3–14.9 × 10−3 amino acid/site/year compared to NA, which evolves at a rate of 9.1 × 10−3 amino acid/site/year [56,88]. While antibody responses against NA are the primary drivers of the antigenic drift, antibody response and altered affinity for NA/HA receptors play a role in NA/HA antigenic drift [33,89]. Furthermore, immunization with the same amount of purified HA and NA resulted in similar increases in antibody titers to each of the antigens, demonstrating that the two antigens have very similar immunogenicity [90]. Due to the lower drift and immunogenic properties of NA, there has been a concerted effort to use NA as a vaccine antigen [20,46,88].

As discussed in the above section, several broadly reactive human NA mAbs have been isolated either after natural infection or post-vaccination. These human NA mAbs display a broad range of protection ranging from homologous protection to different influenza subtypes. For example, human mAbs NA-22, NA-45, NA-63, NA-73 and NA-80 are only active against N9 subtypes [70,81] (Figure 2A). NA-1G05 and NA-2E01 are reactive against all influenza B types [83] (Figure 2D). Lastly, 1E01 and 1G01 are broadly reactive against all influenza A and B types [85] (Figure 2B). The identification of broadly reactive mAbs indicates the presence of conserved epitopes on NA antigen which can be utilized for future NA vaccine candidates (Figure 2C,E). Interestingly, children born after 2006 showed ELISA antibody titers against the ancestral A/South Carolina/1/1918 and B/Lee/1940 influenza virus strains. The ELISA antibody titers correlated positively with NAI titers [42]. Additionally, a recent clinical study in which healthy young adults were challenged with pandemic H1N1 demonstrated differences in the role of HA and NA-specific antibodies. While reduction in virus shedding correlated with HA inhibition titers; fewer symptoms, reduced symptom severity score, reduced duration of symptoms and reduced viral shedding correlated with NAI titers [31]. It has also been shown that NAI titers are independent predictors of immunity against the influenza virus and are an independent correlate of protection [33,34]. These protective mAbs against NA have three different mechanisms of inhibition: (i) direct inhibition of NA catalytic site, (ii) indirect inhibition of NA catalytic site via steric hindrance, and (iii) mAb with little to no NAI activity utilize Fc-FcR-based effector functions [75,85].

Antibodies against NA are not directly involved with preventing virus binding to the host receptors, similar to some anti-HA antibodies. Thus, anti-NA mAbs are not expected to inhibit infection but limit viral spread within the host, reduce morbidity and mortality, decrease viral shedding and reduce transmission to naïve hosts [90,91]. Thus, vaccines containing immunogenic amounts of both HA and NA would be optimal to provide complete protection against influenza virus infection [92]. HA and NA ratios are different for different subtypes and different strains within a subtype [93]. Therefore, NA content and HA:NA ratio in future vaccine candidates need to be standardized. Different assays such as mass spectrometry (MS), isotype dilution MS and capture ELISA to measure the potency of NA in vaccine preparations are under development [93,94,95]. Induction of broadly cross-reactive mAbs has indicated that NA is immunogenic, and that NA antigen contains broadly conserved epitopes.

These studies demonstrate the growing potential of using NA as a vaccine antigen. Advances in emerging platforms (discussed below), a greater understanding of NA structural biology and mAb characterization can inform the design and development of NA vaccine antigens that promote a broad antibody response. Even though the different studies discussed here provide evidence for the use of NA as a vaccine antigen, a slew of questions remain unanswered. The factors that drive long-lasting NA-specific immunity are not well understood. This knowledge could be beneficial in designing NA-based vaccines. What makes natural infection provide a broader and long-lasting antibody response compared to vaccination? Testing of the novel vaccine platforms that use NA as the primary antigen have, so far, been mostly restricted to mice, with only limited platforms assessed in guinea pigs and ferrets (Table 2). Therefore, could a NA vaccine platform that induces robust immune response in mice perform similarly in ferrets and guinea pigs? None of the currently licensed vaccines have standardized amounts of NA. In future vaccine preparations, should NA antigens be standardized to similar amounts or greater amounts than HA to produce a robust immune response? Current studies have shown that NA antigenically drifts at a much slower rate compared to HA. How will the development of a vaccine targeting NA potentially influence the evolution rate of NA? In addition, newly developed assays such as MS, isotype dilution MS and capture ELISA to measure potency of NA in vaccine preparations have been great tools in propelling NA as a vaccine antigen in future vaccine preparations [93,94,95]. Future studies that try to answer the above-mentioned questions along with several others are vital in the development of a future NA-based vaccines.

Table 2. Summary of emerging NA-based vaccine platforms against influenza viruses described in this review. + indicates low immunogenicity, +++ indicates high immunogenicity, N.D. indicates not determined. AA indicates amino acid.

| Platform | NA Antigen Subtype | Animal Model | Immunogenicity | Protection | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inactivated vaccine | 30 AA insertion in seasonal N1 15 AA insertion in N2 |

Mice | +++ +++ |

N.D. | [96] |

| Recombinant NA vaccine | N2 | Human | + | N.D. | [97] |

| Seasonal N1 N2 B/Yamagata/16/88-like B-NA |

Mice | +++ +++ +++ |

Homologous Heterologous |

[27] | |

| Avian N1 Pandemic N1 |

Mice | + | Homologous Partial heterologous |

[98] | |

| N1 | Mice | +++ | Homologous | [99] | |

| N2 | Mice | +++ | Homologous Partial heterologous |

[100] | |

| B-NA | Mice Guinea pigs |

+ | Homologous Heterologous |

[101] | |

| B-NA | Guinea pigs | +++ | Homologous Partial heterologous |

[102] | |

| Virus like particles | Avian N1 | Ferrets | +++ | Homologous | [28] |

| Pandemic N1 | Mice | + | Homologous Heterologous |

[103] | |

| Avian N1 Seasonal N1 |

Mice | +++ | Homologous Heterologous |

[104] | |

| Viral replicon particles | Avian N1 | Chicken | +++ | N.D. | [105] |

| Viral Vector vaccines | Avian N1 Pandemic N1 |

Mice | +++ | Homologous Heterologous Heterosubtypic |

[106] |

| N3 N9 |

Mice | +++ | Homologous | [107] | |

| Nucleic Acid-DNA | Seasonal N1 | Mice | + | Homologous Partial heterologous |

[108] |

| N2 | Mice | + | Homologous Partial heterologous |

[109] | |

| Nucleic Acid-RNA | Seasonal N1 | Mice | +++ | Homologous | [110] |

4. Emerging Platforms for the Development of NA-Based Vaccines

Vaccine candidates that target NA have been frequently revisited since the 1968 Hong Kong influenza A (H3N2) pandemic. The first NA-based inactivated vaccine, which consisted of an irrelevant equine HA and a NA from A/Hong Kong/1/1968 (H3N2), protected against challenge with a virus carrying an antigenically identical NA but a mismatched HA [29]. Despite these encouraging results, NA as a vaccine antigen has only received limited attention in the past. Early immunogenicity studies did not frequently evaluate antibody responses against NA as it was difficult to perform the assay safely, reproducibly and at high throughput [111,112,113]. Furthermore, the amount of NA varied in different viruses and was not easily quantified [20]. Lastly the unstable nature of NAs resulted in conflicting immunogenicity studies [111,114]. As a result, the development of NA-based vaccines using traditional egg-based vaccine platforms has been relatively inactive since 1998 [114]. Emerging vaccine platforms, such as modified inactivated vaccines, recombinant NAs, virus-like particles (VLP), virus replicon particles (VRP), viral vector platforms and nucleic acid vaccines (Table 2), could be used to overcome previously unsuccessful attempts to develop NA as a vaccine antigen. Here we will describe these vaccine platforms and how they have been used in a pre-clinical setting to induce NA antibody responses.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/vaccines9080846

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!