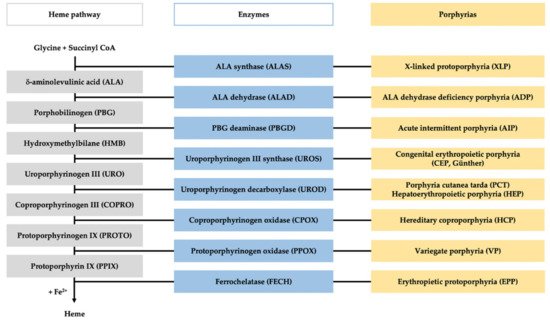

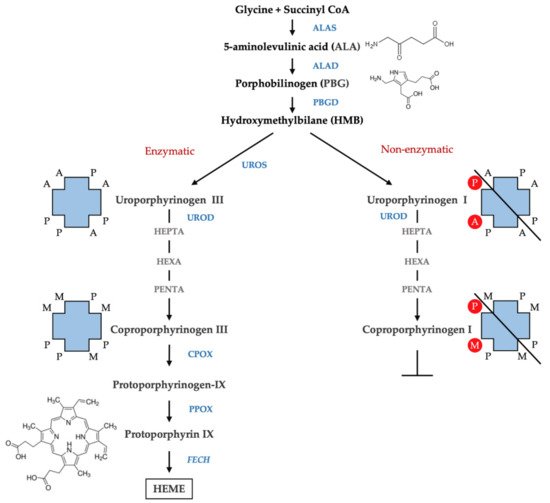

Porphyrias are a group of diseases that are clinically and genetically heterogeneous and originate mostly from inherited dysfunctions of specific enzymes involved in heme biosynthesis.

- porphyria

- ALA (5-aminolevulinic acid)

- PBG (porphobilinogen)

- porphyrins

- HPLC (high-pressure liquid chromatography)

1. Introduction

2. Qualitative Screening Tests

2.1. Plasma Scan

| Porphyrias | ADP/AIP/HCP | VP | PCT/HEP/CEP | EPP/XLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma peak (nm) | 618–622 | 626–628 | 618–620 | 632–636 |

2.2. Fluorocytes

2.3. Hoesch Test

3. Quantitative confirmatory tests

3.1 ALA and PBG determination

The quantification of ALA and PBG forms the first line of laboratory testing for acute porphyria in the event of potentially life-threatening acute neurovisceral attacks [42]. In specialized porphyria diagnostic laboratories, ALA and PBG are commonly quantified after purification, from a spot urine sample, using two commercially available anion-exchange and cation-exchange columns (ClinEasy® Complete Kit for ALA/PBG in Urine, Recipe GmbH, Munich, Germany; ALA/PBG by Column Test, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hermes, CA). This approach enables the selective purification of ALA and PBG, which removes the sample matrix, thereby preventing possible interferences from other compounds [43]. In several certified European laboratories (EPNET), the preferred choice is the ClinEasy® Complete Kit for ALA/PBG in Urine of Recipe for the quantification of both ALA and PBG in the urine. Briefly, urine samples are passed through two overlapping columns – the top column containing an anion exchange resin adsorbs PBG, and the ALA passes through this top column and is subsequently retained by the cation exchange column at the bottom. The adsorbed PBG is eluted from the top column using acetic acid and mixed with Ehrlich’s reagent, upon which the solution develops a purple color, whose intensity is proportional to the amount of the metabolite in the solution. The retained ALA is eluted using sodium acetate, and after derivatization with acetyl-acetone at 100 °C, it is converted into a monopyrrole, which is the measurable form capable of reacting with Ehrlich’s reagent. The absorbance of both PBG and ALA is measured against the blank reagent at 533 nm using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer. Metabolite concentrations are calculated through comparison to the appropriate calibrators (Urine Calibrator Lyophil RECIPE GmbH, Munich, Germany). The results are validated using normal and pathological controls (ClinChek Urine Control L1, L2, RECIPE GmbH, Munich, Germany) reconstituted in high purity water and stored in single-dose aliquots at –20 °C until use. The concentration values are expressed as µmol/mmol creatine; ALA and PBG are considered over the normal limits if the concentration values are >5 and >1.5 µmol/mmol creatine, respectively. A high level of ALA and a normal level of PBG indicate either the rare ALAD deficiency porphyria or the more common heavy-metal intoxication and hereditary tyrosinemia type I caused by the inhibition of ALAD by lead and succinyl-acetone, respectively [44;45]. High levels of up to 20–50 times the normal values of both the metabolites establish the diagnosis of an acute attack, while moderate ALA and PBG levels could indicate VP and HCP [6]. The majority of the patients affected by acute porphyria after the symptomatic period may revert completely, while a few might become clinically asymptomatic along with persistent moderate increments in the heme precursors.

Over the last decades, the technique of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has been employed in numerous clinical biochemistry applications. In comparison to traditional methods, LC-MS/MS has major advantages of higher analytical sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic reliability. About porphyria, the LC-MS/MS technique has been applied successfully for the simultaneous quantification of ALA and PBG in urine and plasma samples [46-49].

Notably, significantly lower levels of urinary ALA and PBG could be measured using MS-based methods, particularly for healthy individuals, confirming that these methods had a higher selectivity compared to the colorimetric ones [43]. The difference is probably due to the presence of contaminant molecules in the urine, which react with Ehrlich’s reagent. Recently, LC-MS/MS measurements of a large number of healthy subjects established the upper limit of the normal values (ULN) of ALA and PBG as 1.47 and 0.137 µmol/mmol creatinine, respectively [50], and it was reported that during an acute attack, these values could reach 40 and 55 µmol/mmol creatinine, respectively [48]. Moreover, sample preparation using a solid-phase extraction (SPE) system allows the detection of concentrations as low as 0.05 µM [49]. Therefore, measurements of porphyrin precursors in plasma and tissue samples have become achievable. Floderus et al. quantified the plasma levels of ALA and PBG in 10 asymptomatic AIP patients and reported the mean concentrations to be 1.7 and 3.1 µmol/L, respectively, which were significantly higher than those of the healthy subjects (0.38 and <0.12 µmol/L, respectively) [46]. However, during an acute attack of porphyria, ALA and PBG concentrations may increase dramatically, up to 13 µmol/L [47].

Since the variation over the time of the plasma concentrations of ALA and PBG is reported to be highly correlated with urinary concentrations [46], these measurements may contribute to the monitoring of AIP patients during the course of an acute attack [51], particularly if the patients are in an anuric state. Plasma ALA and PBG levels could also be useful in evaluating the safety and the pharmacokinetic effects of the existing or future therapies in AHP patients [52]. However, not all hospitals are equipped with LC-MS/MS, restricting this technique to a few specialized centers.

3.2 Measurement of urine porphyrins

The differential diagnosis of porphyria relies on the measurements of porphyrins and relative isomers in urine, feces and plasma. As plasma porphyrin separation find a practical application only in patient with renal failure, this topic is not treated in this review.

Although various methods have been developed for the analysis of urine porphyrins, reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography coupled with fluorescence detection (FLD-HPLC) has become the gold standard method for this purpose [53-55]. The success of this technique is attributed to its capacity to separate the physiologically relevant porphyrins as free acids and resolve type I and type III porphyrin isomers simultaneously [56]. Since the fluorescence detection enhances the specificity of analytic method, matrix extraction procedures are not required and acidic urine samples could be directly injected.

Typical chromatographic runs are performed on C18-bonded silica stationary phase using a linear gradient elution system from 10% (v/v) acetonitrile in 1M ammonium acetate, pH 5.16 (phase A) and 10% acetonitrile in methanol (phase B). Porphyrins containing from two to eight carboxylic groups, including the resolution of type I and type III isomers could be achieved in less of 30 minutes. The excitation and emission wavelength ranges used are usually around 395–420 nm and 580–620 nm, respectively. Direct standardization is obtained by comparison to chromatographic runs of suitable calibration standard that are now commercially available (RECIPE GmbH, Munich, Germany; Chromsystems GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany). Total urine porphyrin measurement is calculated as sum of chromatographic fractions and the single fractions as relative percentages. As spot urine samples are commonly used, results should be normalized on creatinine concentration.

In normal subjects, the total porphyrins excretion is found below 35 nmol/mmol creatinine, COPRO predominate on URO while hepta-, hexa-, and penta-carboxyl porphyrins are present only in small amounts. Moreover, relative concentrations of COPRO isomer III are higher than COPRO isomer I.

In porphyric patients, the excretion of urinary porphyrins varies in relation to the enzymatic defect underlying the particular type of porphyria and with respect to the disease stage [57]. URO, both the type I and type III isomers, and hepta- type III are evidently raised in PCT and HEP since the type I isomers of URO and COPRO are detected in CEP almost exclusively. In acute hepatic porphyrias (AIP, VP, and HCP), porphyrins excretion is extremely variable from normal values in asymptomatic phase to very high values observed during the acute exacerbation of disease. In AIP, a pattern of marked elevation of URO I and III isomers, along with less pronounced elevations of COPRO III and I, is detected, while HCP and VP demonstrate a marked elevation of COPRO III. In EPP, total urine porphyrins are normal however, abnormal chromatographic profiles are frequently observed. Particularly, higher relative amounts of COPRO I are commonly observed as a consequence of potential hepatic implications. In fact, increased levels of porphyrins excretion may also occur in several physio-pathological conditions including hereditary hyperbilirubinemias, toxic syndromes or liver diseases [58].

Recently, protocols using mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to separate and detect porphyrins have also been reported to facilitate the clinical diagnosis of porphyria [48]. However, the low prevalence of this equipment in hospitals restricts the application of such protocols to the identification and characterization of unknown porphyrins in research.

3.3 Analysis of fecal porphyrins

Two different systems may be employed for the analysis of fecal porphyrins. First, the total fecal porphyrins can be quantified using a spectrophotometric [58;59] or fluorimetric [60] method and then separated by HPLC to obtain porphyrin patterns [61]. Second, total fecal porphyrins can be calculated as the sum of fractions following HPLC analysis [62]. The former approach is considered more suitable for routine use in clinical analysis, while the latter is technically more correct and, therefore, allows quantification with higher reliability [63].

In the widely employed method reported by Lockwood et al., porphyrins are extracted from a small sample of feces in the aqueous acid phase using the solvent partition [59]. Briefly, 25–50 mg of feces are processed by sequential addition of 1 mL of concentrated HCl to dissolve the organic matrix, 3 mL of diethyl ether to eliminate the contaminants – chlorophylls and carotenoid pigments, and 3 mL water to avoid any alteration in protoporphyrin. The hydrochloric acid extract is then analyzed by performing a spectrophotometric scan between 370 nm and 430 nm, which includes the Soret region. After background signal subtraction, the absorbance measured at the maximum peak is used for calculating the total porphyrin content. It is also necessary to separately evaluate the water percentage in the feces sample to report the result as nmol/g dry weight (total fecal porphyrin normal value < 200 nmol/g dry weight) [59]. Although no commercial reference material is available, an internal quality control (ICQ) could be prepared from the patient’s specimens to check the day-today reproducibility. The obtained hydrochloric acid extracts may be directly injected into HPLC systems for subsequent characterization using the same protocol as the one used for urine porphyrins chromatography. Calibration solution is prepared adding appropriate concentrations of meso- and proto-porphyrin to the urine calibrators.

The fecal excretion of porphyrins increases in hepatic PCT, HCP and VP, in erythropoietic CEP and HEP and sometimes in EPP and XLP. The detection of the specific patterns of fecal porphyrins allows the differentiation of these enzymatic disorders that otherwise share similar clinical presentation and overlapping biochemical characteristics. Feces samples from healthy subjects, as well as from porphyria patients, contain varying amounts of dicarboxylic porphyrins, particularly deutero-, pempto-, and meso-porphyrins, in addition to protoporphyrin. These dicarboxylic porphyrins lack a diagnostic relevance, depending on the gut microflora [64] and even on the diet [65]. Moreover, gastrointestinal bleeding may interfere with feces analysis, causing anomalous increase in the levels of protoporphyrin and the dicarboxylic porphyrins derived from it [66]. Tricarboxylic porphyrins remain generally undetected, although the presence of harderoporphyrin in feces [67] played a major role in the identification of a variant of homozygous HCP (harderoporphyria). Uroporphyrin is excreted prevalently in the urine and may be detected in feces only in trace amounts.

Fecal porphyrins profiles of PCT and HEP are the most complex, with a wide range of peaks. It is possible to recognize COPRO I isomer, which always prevails over COPRO III, although increasing signals corresponding to epta-, esa-, and penta-porphyrins, with the prevalence of isomer III, are also observed. Since UROD is the enzyme that catalyzes the sequential decarboxylation of uroporphyrin to coproporphyrin, its activity deficit leads to the accumulation of all porphyrin intermediates in PCT. In HEP, the activity of UROD is severely compromised and the porphyrins containing a higher number of carboxylic groups are represented more. PCT chromatographic profiles are also characterized by the presence of isocoproporphyrin and its derived metabolites hydroxy-, keto-, deethyl-, dehydro-isocoproporphyrin. These molecules, are commonly identified as diagnostic sign of symptomatic PCT [64] nevertheless diagnoses based on the presence of isocoproporphyrin in the feces are prone to be erroneous.

Chromatographic profiles of fecal porphyrins of AIP and ADP patients are similar to those of healthy subjects. On the other hand, the fecal porphyrin chromatograms of HCP patients are easily recognizable by the presence of a prominent peak corresponding to COPRO III. Peaks for both PROTO and COPRO III are elevated in the chromatographic profiles of VP patients. In particular conditions, such as hepatitis or drug consumption, which inhibit the UROD activity, HCP and VP patients may exhibit fecal porphyrin patterns quite similar to those of PCT patients, including the isocoproporphyrin series. Since the relative abundance of COPRO III is always higher compared to isomer I in VP and HCP, while the opposite is true for PCT, the ratio between the coproporphyrin isomers serves as a suitable diagnostic parameter [68;69]. The fecal porphyrins pattern in CEP contains an elevated peak corresponding to COPRO I. Finally, the chromatograms of EPP and XLP patients present an elevated PROTO peak.

3.4 Erythrocyte porphyrins measurement

Initially, to assay total erythrocyte porphyrins, fluorometric methods involving the acid extraction procedure that converted ZnPP to its metal-free form PPIX were used [70]. Later, when it became possible to detect ZnPP in the whole blood samples without prior acid extraction, hematofluorometry methods were developed for this assessment [71;72]. Finally, the application of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with fluorometric detection to separate and quantify unchelated PPIX and ZnPP simultaneously commenced [73;74]. A method using derivative variable-angle synchronous fluorescence (DVASF) for determining PPIX and ZnPP simultaneously in whole blood sample, avoiding the spectral compensation factor for PPIX and the chromatographic separation has been also reported [75]. A simple, rapid, and specific HPLC method is here described. Whole blood samples are collected in vacutainer tubes containing the anticoagulant K3EDTA and then stored at –20 °C in the dark. At the time of analysis, samples are thawed to room temperature and mixed well, followed by the dilution of 60 µL aliquots in 200 µL of lysing solution (4% aqueous formic acid) and the extraction of porphyrins using 900 µL acetone. An aliquot of the extracted porphyrins is injected directly into the HPLC system, using a Chromsystem C-18 column (Chromsystems GmbH, Gräfelfing, Germany) for chromatographic for separations. ZnPP and PPIX are eluted in isocratic conditions (90% methanol in aqueous 1% acetic acid solution) at 42 °C and subsequently detected using fluorescence excitation/emission wavelengths of 400 nm/620 nm (1–7 min) and 387/633 nm (7–15 min), respectively. In order to quantify PPIX and ZnPP, homemade calibration curves are used, and the analytes are observed to be linear in the concentration ranges of 1.5 - 50 µg/dL and 2 - 100 µg/dL, respectively. The results are reported as the sum of PPIX and ZnPP peaks, and the concentrations in the blood are expressed as both µg/g Hb and relative percentage of each porphyrin. The normal level for the sum is <3 µg/g Hb and normal percentage ranges are ZnPP 80 – 90 % and PPIX 10 - 20%. Erythrocyte porphyrins are abnormally increased in EPP, XLP, CEP, and HEP, although the percentage of each porphyrin differs among these disorders. It is noteworthy that elevated erythrocyte protopophyrins along with normal ZnPP support the diagnosis of the classical form of EPP, while an elevation in both components with balanced percentages occurs in the XLP. High levels of erythrocyte porphyrins also occur in the case of exposure to lead from both environmental and occupational conditions [76], in iron deficiency [77], as well as in sideroblastic anemia, all of which are conditions associated with elevated Zn PP. In CEP and HEP the predominant porphyrins may be uroporphyrins or ZnPP depending on phenotype expression.

The entry is from https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11081343

References

- Balwani M, Desnick RJ: The porphyrias: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Blood 2012;120:4496-4504.

- Besur S, Hou W, Schmeltzer P, Bonkovsky HL: Clinically important features of porphyrin and heme metabolism and the porphyrias. Metabolites 2014;4:977-1006.

- Stolzel U, Doss MO, Schuppan D: Clinical Guide and Update on Porphyrias. Gastroenterology 2019;157:365-381.

- Sassa S: Modern diagnosis and management of the porphyrias. Br J Haematol 2006;135:281-292.

- Wang B, Rudnick S, Cengia B, Bonkovsky HL: Acute Hepatic Porphyrias: Review and Recent Progress. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:193-206.

- Puy H, Gouya L, Deybach JC: Porphyrias. Lancet 2010;375:924-937.

- Linenberger M, Fertrin KY: Updates on the diagnosis and management of the most common hereditary porphyrias: AIP and EPP. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2020;2020:400-410.

- Karim Z, Lyoumi S, Nicolas G, Deybach JC, Gouya L, Puy H: Porphyrias: A 2015 update. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015;39:412-425.

- Bissell DM, Anderson KE, Bonkovsky HL: Porphyria. N Engl J Med 2017;377:862-872.

- Woolf J, Marsden JT, Degg T, Whatley S, Reed P, Brazil N, Stewart MF, Badminton M: Best practice guidelines on first-line laboratory testing for porphyria. Ann Clin Biochem 2017;54:188-198.

- Ventura P, Cappellini MD, Biolcati G, Guida CC, Rocchi E: A challenging diagnosis for potential fatal diseases: recommendations for diagnosing acute porphyrias. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:497-505.

- Poblete-Gutierrez P, Wiederholt T, Merk HF, Frank J: The porphyrias: clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Dermatol 2006;16:230-240.

- Poh-Fitzpatrick MB, Lamola AA: Direct spectrofluorometry of diluted erythrocytes and plasma: a rapid diagnostic method in primary and secondary porphyrinemias. J Lab Clin Med 1976;87:362-370.

- Di Pierro E, Ventura P, Brancaleoni V, Moriondo V, Marchini S, Tavazzi D, Nascimbeni F, Ferrari MC, Rocchi E, Cappellini MD: Clinical, biochemical and genetic characteristics of Variegate Porphyria in Italy. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy -le-grand) 2009;55:79-88.

- Poh-Fitzpatrick MB: A plasma porphyrin fluorescence marker for variegate porphyria. Arch Dermatol 1980;116:543-547.

- Chularojanamontri L, Tuchinda C, Srisawat C, Neungton N, Junnu S, Kanyok S: Utility of plasma fluorometric emission scanning for diagnosis of the first 2 cases reports of variegate porphyria: a very rare type of porphyrias in Thai. J Med Assoc Thai 2008;91:1915-1919.

- Enriquez de SR, Sepulveda P, Moran MJ, Santos JL, Fontanellas A, Hernandez A: Clinical utility of fluorometric scanning of plasma porphyrins for the diagnosis and typing of porphyrias. Clin Exp Dermatol 1993;18:128-130.

- Hift RJ, Meissner D, Meissner PN: A systematic study of the clinical and biochemical expression of variegate porphyria in a large South African family. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:465-471.

- Da Silva V, Simonin S, Deybach JC, Puy H, Nordmann Y: Variegate porphyria: diagnostic value of fluorometric scanning of plasma porphyrins. Clin Chim Acta 1995;238:163-168.

- Sies CW, Davidson JS, Florkowski CM, Johnson RN, Potter HC, Woollard GA, George PM: Plasma fluorescence scanning did not detect latent variegate porphyria in nine patients with non-p.R59W mutations. Pathology 2005;37:324-326.

- Zaider E, Bickers DR: Clinical laboratory methods for diagnosis of the porphyrias. Clin Dermatol 1998;16:277-293.

- Osipowicz K, Kalinska-Bienias A, Kowalewski C, Wozniak K: Development of bullous pemphigoid during the haemodialysis of a young man: case report and literature survey. Int Wound J 2017;14:288-292.

- Bergler-Czop B, Brzezinska-Wcislo L: Pseudoporphyria induced by hemodialysis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2014;31:53-55.

- Handler NS, Handler MZ, Stephany MP, Handler GA, Schwartz RA: Porphyria cutanea tarda: an intriguing genetic disease and marker. Int J Dermatol 2017;56:e106-e117.

- Deacon AC, Elder GH: ACP Best Practice No 165: front line tests for the investigation of suspected porphyria. J Clin Pathol 2001;54:500-507.

- Rimington C, CRIPPS DJ: BIOCHEMICAL AND FLUORESCENCE-MICROSCOPY SCREENING-TESTS FOR ERYTHROPOIETIC PROTOPORPHYRIA. Lancet 1965;1:624-626.

- Lau KC, Lam CW: Automated imaging of circulating fluorocytes for the diagnosis of erythropoietic protoporphyria: a pilot study for population screening. J Med Screen 2008;15:199-203.

- Piomelli S, Lamola AA, Poh-Fitzpatrick MF, Seaman C, Harber LC: Erythropoietic protoporphyria and lead intoxication: the molecular basis for difference in cutaneous photosensitivity. I. Different rates of disappearance of protoporphyrin from the erythrocytes, both in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Invest 1975;56:1519-1527.

- Cordiali FP, Macri A, Trento E, D'Agosto G, Griso D, Biolcati F, Ameglio F: Flow cytometric analysis of fluorocytes in patients with erythropoietic porphyria. Eur J Histochem 1997;41 Suppl 2:9-10.

- Brun A, Steen HB, Sandberg S: Erythropoietic protoporphyria: a quantitative determination of erythrocyte protoporphyrin in individual cells by flow cytometry. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1988;48:261-267.

- Schleiffenbaum BE, Minder EI, Mohr P, Decurtins M, Schaffner A: Cytofluorometry as a diagnosis of protoporphyria. Gastroenterology 1992;102:1044-1048.

- Anderson KE, Lobo R, Salazar D, Schloetter M, Spitzer G, White AL, Young RM, Bonkovsky HL, Frank EL, Mora J, Tortorelli S: Biochemical Diagnosis of Acute Hepatic Porphyria: Updated Expert Recommendations for Primary Care Physicians. Am J Med Sci 2021.

- Watson CJ, Schwartz S: A Simple Test for Urinary Porphobilinogen. Experimental Biology and Medicine 1941;47:393.

- Watson CJ, TADDEINI L, BOSSENMAIER I: PRESENT STATUS OF THE EHRLICH ALDEHYDE REACTION FOR URINARY PORPHOBILINOGEN. JAMA 1964;190:501-504.

- With TK: Screening test for acute porphyria. Lancet 1970;2:1187-1188.

- Bonkovsky HL, Barnard GF: Diagnosis of porphyric syndromes: a practical approach in the era of molecular biology. Semin Liver Dis 1998;18:57-65.

- CALVO DE MORA ALMAZÁN M, ACUÑA M, GARRIDO-ASTRAY C, ARCOS PULIDO B, GÓMEZ-ABECIA S, CHICOT LLANO M, GONZÁLEZ PARRA E, GRACIA IGUACEL C, ALONSO ALONSO PP, EGIDO J, ENRÍQUEZ DE SALAMANCA R: Acute porphyria in an intensive care unit. Emergencias 2012;24:454-458.

- Lamon J, With TK, Redeker AG: The Hoesch test: bedside screening for urinary porphobilinogen in patients with suspected porphyria. Clin Chem 1974;20:1438-1440.

- McEwen J, Paterson C: Drugs and false-positive screening tests for porphyria. Br Med J 1972;1:421.

- TADDEINI L, KAY IT, Watson CJ: Inhibition of the Ehrlich's reaction of porphobilinogen by indican and related compounds. Clin Chim Acta 1962;7:890-891.

- Castelbón Fernández FJ, Solares Fernandez I, Arranz Canales E, ENRÍQUEZ DE SALAMANCA R, Morales Conejo M: Protocol for patients with suspected acute porphyria. Rev Clin Esp 2020;220:592-596.

- Aarsand AK, Petersen PH, Sandberg S: Estimation and application of biological variation of urinary delta-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen in healthy individuals and in patients with acute intermittent porphyria. Clin Chem 2006;52:650-656.

- MAUZERALL D, GRANICK S: The occurrence and determination of delta-amino-levulinic acid and porphobilinogen in urine. J Biol Chem 1956;219:435-446.

- Kelada SN, Shelton E, Kaufmann RB, Khoury MJ: d-Aminolevulinic Acid Dehydratase Genotype and Lead Toxicity: A HuGE Review. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154.

- Wyss PA, Carter BE, Roth KS: delta-Aminolevulinic acid dehydratase: effects of succinylacetone in rat liver and kidney in an in vivo model of the renal Fanconi syndrome. Biochem Med Metab Biol 1992;48:86-89.

- Floderus Y, Sardh E, Moller C, Andersson C, Rejkjaer L, Andersson DE, Harper P: Variations in porphobilinogen and 5-aminolevulinic acid concentrations in plasma and urine from asymptomatic carriers of the acute intermittent porphyria gene with increased porphyrin precursor excretion. Clin Chem 2006;52:701-707.

- Benton CM, Couchman L, Marsden JT, Rees DC, Moniz C, Lim CK: Direct and simultaneous quantitation of 5-aminolaevulinic acid and porphobilinogen in human serum or plasma by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Chromatogr 2013;27:267-272.

- Benton CM, Lim CK: Liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry of haem biosynthetic intermediates: a review. Biomed Chromatogr 2012;26:1009-1023.

- Zhang J, Yasuda M, Desnick RJ, Balwani M, Bishop D, Yu C: A LC-MS/MS method for the specific, sensitive, and simultaneous quantification of 5-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2011;879:2389-2396.

- Agarwal S, Habtemarium B, Xu Y, Simon AR, Kim JB, Robbie GJ: Normal reference ranges for urinary delta-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen levels. JIMD Rep 2021;57:85-93.

- Sardh E, Harper P, Andersson DE, Floderus Y: Plasma porphobilinogen as a sensitive biomarker to monitor the clinical and therapeutic course of acute intermittent porphyria attacks. Eur J Intern Med 2009;20:201-207.

- Sardh E, Rejkjaer L, Andersson DE, Harper P: Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmocodynamics of recombinant human porphobilinogen deaminase in healthy subjects and asymptomatic carriers of the acute intermittent porphyria gene who have increased porphyrin precursor excretion. Clin Pharmacokinet 2007;46:335-349.

- Lim CK, Li FM, Peters TJ: High-performance liquid chromatography of porphyrins. J Chromatogr 1988;429:123-153.

- Macours P, Cotton F: Improvement in HPLC separation of porphyrin isomers and application to biochemical diagnosis of porphyrias. Clin Chem Lab Med 2006;44:1433-1440.

- Schreiber WE, Raisys VA, Labbe RF: Liquid-chromatographic profiles of urinary porphyrins. Clin Chem 1983;29:527-530.

- Lim CK, Rideout JM, Wright DJ: Separation of porphyrin isomers by high-performance liquid chromatography. Biochem J 1983;211:435-438.

- Hindmarsh JT, Oliveras L, Greenway DC: Biochemical differentiation of the porphyrias. Clin Biochem 1999;32:609-619.

- Rimington C: The isolation of a monoacrylic tri propionic porphyrin from meconium and its bearing on the conversion of coproporphyrin to protoporphyrin. S Afr Med J 1971;187-189.

- Lockwood WH, Poulos V, Rossi E, Curnow DH: Rapid procedure for fecal porphyrin assay. Clin Chem 1985;31:1163-1167.

- Pudek MR, Schreiber WE, Jamani A: Quantitative fluorometric screening test for fecal porphyrins. Clin Chem 1991;37:826-831.

- Lim CK, Peters TJ: Urine and faecal porphyrin profiles by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography in the porphyrias. Clin Chim Acta 1984;139:55-63.

- Beukeveld GJ, Wolthers BG, van Saene JJ, de Haan TH, de Ruyter-Buitenhuis LW, van Saene RH: Patterns of porphyrin excretion in feces as determined by liquid chromatography; reference values and the effect of flora suppression. Clin Chem 1987;33:2164-2170.

- Zuijderhoudt FM, Kamphuis JS, Kluitenberg WE, Dorresteijn-de BJ: Precision and accuracy of a HPLC method for measurement of fecal porphyrin concentrations. Clin Chem Lab Med 2002;40:1036-1039.

- Elder GH: Identification of a group of tetracarboxylate porphyrins, containing one acetate and three propionate -substituents, in faeces from patients with symptomatic cutaneous hepatic porphyria and from rats with porphyria due to hexachlorobenzene. Biochem J 1972;126:877-891.

- Rose IS, Young GP, St John DJ, Deacon MC, Blake D, Henderson RW: Effect of ingestion of hemoproteins on fecal excretion of hemes and porphyrins. Clin Chem 1989;35:2290-2296.

- Cohen A, Boeijinga JK, van Haard PM, Schoemaker RC, van Vliet-Verbeek A: Gastrointestinal blood loss after non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Measurement by selective determination of faecal porphyrins. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1992;33:33-38.

- Nordmann Y, Grandchamp B, de VH, Phung L, Cartigny B, Fontaine G: Harderoporphyria: a variant hereditary coproporphyria. J Clin Invest 1983;72:1139-1149.

- Kuhnel A, Gross U, Jacob K, Doss MO: Studies on coproporphyrin isomers in urine and feces in the porphyrias. Clin Chim Acta 1999;282:45-58.

- Jacob K, Doss MO: Excretion pattern of faecal coproporphyrin isomers I-IV in human porphyrias. Eur J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1995;33:893-901.

- Heller SR, Labbe RF, Nutter J: A simplified assay for porphyrins in whole blood. Clin Chem 1971;17:525-528.

- Lamola AA, Joselow M, Yamane T: Zinc protoporphyrin (ZPP): a simple, sensitive fluorometric screening test for lead poisoning. Clin Chem 1975;21:93-97.

- Blumberg WE, Eisinger J, Lamola AA, Zuckerman DM: The hematofluorometer. Clin Chem 1977;23:270-274.

- Bailey GG, Needham LL: Simultaneous quantification of erythrocyte zinc protoporphyrin and protoporphyrin IX by liquid chromatography. Clin Chem 1986;32:2137-2142.

- Chen Q, Hirsch RE: A direct and simultaneous detection of zinc protoporphyrin IX, free protoporphyrin IX, and fluorescent heme degradation product in red blood cell hemolysates. Free Radical Research 2006;40:285-294.

- Zhou PC, Huang W, Zhang RB, Zou ZX, Luo HD, Falih AA, Li YQ: A simple and rapid fluorimetric method for simultaneous determination of protoporphyrin IX and zinc protoporphyrin IX in whole blood. Appl Spectrosc 2008;62:1268-1273.

- Sassa S, Granick JL, GRANICK S, Kappas A, Levere RD: Studies in lead poisoning. I. Microanalysis of erythrocyte protoporphyrin levels by spectrophotometry in the detection of chronic lead intoxication in the subclinical range. Biochem Med 1973;8:135-148.

- Braun J: Erythrocyte zinc protoporphyrin. Kidney Int Suppl 1999;69:S57-S60

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics11081343