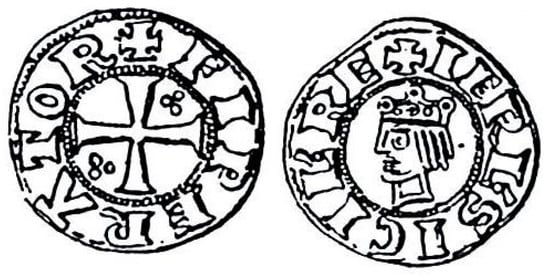

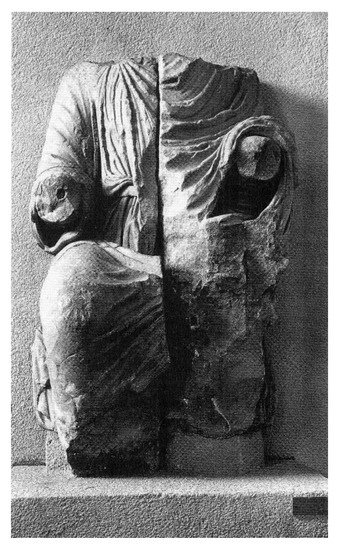

Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, King of Sicily (1208–1250). Frederick II of Hohenstaufen was the second king of the Swabian dynasty to sit on the throne of Sicily. He was crowned in 1198, but, in consideration of his young age, he only ruled independently from 1208 to 1250 (the year of his death). He not only held the title of King of Sicily but also was the King of Germany (or of the Romans), the King of Jerusalem, and, above all, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. His most relevant and innovative iconographic representations were in Southern Italy. For this reason, we focus on the images in this geographical context. In particular, we have nine official (that is, those commissioned directly by him or his entourage) representations of him: the bull (in three main versions), the seal (in three main versions), five coins (four denari and one augustale), the statue of the Capua Gate, and the lost image of the imperial palace in Naples.

- royal images

- royal iconography

- kings of Sicily

- Swabian dynasty

- Frederick II of Hohenstaufen

1. Introduction

2. Bulls and Seals

3. The Denari

4. The Augustale

5. The Statue of the Capua Gate

6. The Lost Image of the Imperial Palace in Naples

7. Conclusions

References

- Kantorowicz, E.H. Federico II imperatore; Garzanti: Milano, Italy, 2000; (Original edition Berlin, 1927–1931).

- Abulafia, D. Federico II. Un imperatore medievale; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1993; (Original edition London, 1988).

- Toubert, P.; Paravicini Bagliani, A. (Eds.) Federico II; Sellerio: Palermo, Italy, 1994.

- Calò Mariani, M.S.; Cassano, R. (Eds.) Federico II. Immagine e potere; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1995.

- Fonseca, C.D. (Ed.) Federico II e l’Italia. Percorsi, Luoghi, Segni e Strumenti; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1995.

- Fonseca, C.D. (Ed.) Mezzogiorno. Federico II. Mezzogiorno; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1999.

- Zecchino, O. (Ed.) Enciclopedia fridericiana; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005.

- Fansa, M.; Ermete, K. (Eds.) Kaiser Friedrich II. (1194–1250). Welt und Kultur des Mittelmeerraums; von Zabern: Mainz am Rhein, Germany, 2008.

- Stürner, W. Federico II e l’apogeo dell’Impero; Salerno: Roma, Italy, 2009; (Original edition Darmstadt, 1992–2000).

- Houben, H. Federico II. Imperatore, uomo, mito; il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2009; (Original edition Stuttgart, 2008).

- Rader, O. Friedrich II.: der Sizilianer auf dem Kaiserthron. Eine Biographie; Beck: München, Germany, 2010.

- Vagnoni, M. Epifanie del corpo in immagine dei re di Sicilia (1130–1266); Palermo University Press: Palermo, Italy, 2019.

- Posse, O. Die Siegel der deutschen Kaiser und Könige von 751 bis 1913; Wilhelm und Bertha von Baensch Stiftung: Dresden, Germany, 1909–1913.

- De Venere, C. (Ed.) Gli Svevi in Italia meridionale. Guida alla mostra; Adda: Bari, Italy, 1980.

- Haussherr, R. (Ed.) Die Zeit der Staufer. Geschichte-Kunst-Kultur; Württembergisches Landesmuseum: Stuttgart, Germany, 1977–1979.

- La Duca, R. (Ed.) L’età normanna e sveva in Sicilia. Mostra storico-documentaria e bibliografica; Assemblea Regionale Siciliana: Palermo, Italy, 1994.

- Wieczorek, A.; Schneidmüller, B.; Weinfurter, S. (Eds.) Die Staufer und Italien. Drei Innovationsregionen im mittelalterlichen Europa; Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft: Darmstadt, Germany, 2010.

- Vagnoni, M. Imperator Romanorum. L’iconografia di Federico II di Svevia. In Quei maledetti normanni. Studi offerti a Errico Cuozzo per i suoi settant’anni da Colleghi, Allievi, Amici; Martin, J.-M., Alaggio, R., Eds.; Centro Europeo di Studi Normanni: Ariano Irpino-Napoli, Italy, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 1225–1234.

- Koch, W. Kanzlei- und Urkundenwesen Kaiser Friedrichs II. Eine Standortbestimmung. In Mezzogiorno. Federico II. Mezzogiorno; Fonseca, C.D., Ed.; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1999; pp. 595–619.

- Koch, W. Cancelleria dell’impero. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 1, ad vocem.

- Travaini, L. Hohenstaufen and Angevin Denari of Sicily and Southern Italy: Their Mint Attributions. Numismatic Chronicle 1993, 153, 91–135.

- Corpus Nummorum Italicorum. Primo tentativo di un catalogo generale delle monete medievali e moderne coniate in Italia o da italiani in altri paesi; Tipografia della Regia Accademia dei Lincei: Roma, Italy, 1910–1943.

- Spahr, R. Le monete siciliane. Dai Bizantini a Carlo I d’Angiò (582–1282); Association Internationale des Numismates Professionnels: Zürich, Switzerland, 1976.

- Ricci, S. Gli “augustali” di Federico II. Studi Medievali 1928, 1, 59–73.

- Kowalski, H. Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau 1976, 55, 77–150.

- Claussen, P.C. Creazione e distruzione dell’immagine di Federico II nella storia dell’arte. Che cosa rimane? In Federico II. Immagine e potere; Calò Mariani, M.S., Cassano, R., Eds.; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1995; pp. 69–81.

- Travaini, L. Augustale. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 1, ad vocem.

- Punzi, F. L’augustale. In Le monete della Peucezia. La monetazione sveva nel regno di Sicilia; Circolo Numismatico Pugliese: Bari, Italy, 2010; pp. 189–209.

- Travaini, L. Zecche e monete nello Stato federiciano. In Federico II.; Toubert, P., Paravicini Bagliani, A., Eds.; Sellerio: Palermo, Italy, 1994; Volume 1, Federico II e il mondo Mediterraneo; pp. 146–164.

- Pannuti, M. La monetazione di Federico II di Svevia nell’Italia meridionale e in Sicilia. In Federico II. Immagine e potere; Calò Mariani, M.S., Cassano, R., Eds.; Marsilio: Venezia, Italy, 1995; pp. 58–61.

- Panvini Rosati, F. Federico II “mutator monetae”. In Federico II e l’Italia. Percorsi, Luoghi, Segni e Strumenti; Fonseca, C.D., Ed.; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1995; pp. 75–77.

- Travaini, L. Le monete di Federico II: il contributo numismatico alla ricerca storica. In Mezzogiorno. Federico II. Mezzogiorno; Fonseca, C.D., Ed.; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1999; pp. 655–668.

- Travaini, L. Monetazione. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 2, ad vocem.

- Travaini, L. La monetazione sveva nel Regno di Sicilia. In Le monete della Peucezia. La monetazione sveva nel regno di Sicilia; Circolo Numismatico Pugliese: Bari, Italy, 2010; pp. 325–330.

- Vagnoni, M. Caesar semper Augustus. Un aspetto dell’iconografia di Federico II di Svevia. Mediaeval Sophia. Studi e ricerche sui saperi medievali 2008, 2/1, 142–161.

- D’Onofrio, M. Capua, porta di. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 1, ad vocem.

- Speciale, L.; Torriero, G. Epifania del potere: struttura e immagine nella Porta di Capua. In Medioevo: immagini e ideologie; Quintavalle, A.C., Ed.; Mondadori Electa: Milano, Italy, 2005; pp. 459–474.

- Wagner, B. Die Bauten des Stauferkaisers Friedrich II. Monumente des Heiligen Römischen Reiches; Dissertation-Verlag im Internet: Berlin, Germany, 2005.

- Speciale, L. Immagini per la storia. Ideologia e rappresentazione del potere nel mezzogiorno medievale; Fondazione CISAM: Spoleto, Italy, 2014.

- De Stefano, A. L’idea imperiale di Federico II; Vallecchi: Firenze, Italy, 1927.

- Delle Donne, F. Il potere e la sua legittimazione. Letteratura encomiastica in onore di Federico II di Svevia; Nuovi Segnali: Arce, Italy, 2005.

- Vagnoni, M. Lex animata in terris. Sulla sacralità di Federico II di Svevia. Mediaeval Sophia. Studi e ricerche sui saperi medievali 2009, 3/1, 101–118.

- Zecchino, O. Liber Constitutionum. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 2, ad vocem.

- Carfora, C. Capua. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 1, ad vocem.

- Zecchino, O. Il «Liber Constitutionum» nel contrasto tra Federico II e Gregorio IX. In Il Papato e i Normanni. Temporale e Spirituale in età normanna; D’Angelo, E., Leonardi, C., Eds.; SISMEL: Firenze, Italy, 2011; pp. 23–44.

- Bologna, F. I pittori alla corte angioina di Napoli 1266–1414. E un riesame dell’arte nell’età fridericiana; Ugo Bozzi: Roma, Italy, 1969.

- Van Cleve, T.C. The Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. Immutator Mundi; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1972.

- Frugoni, C. L’antichità: dai «Mirabilia» alla propaganda politica. In Memoria dell’antico nell’arte italiana; Settis, S., Ed.; Einaudi: Torino, Italy, 1984; Volume 1, L’uso dei classici; pp. 6–72.

- Delle Donne, F. Una perduta raffigurazione federiciana descritta da Francesco Pipino e la sede della cancelleria imperiale. Studi Medievali 1997, 38, 737–749.

- Aceto, F. La pittura sveva. In Mezzogiorno. Federico II. Mezzogiorno; Fonseca, C.D., Ed.; De Luca: Roma, Italy, 1999; pp. 749–776.

- Little, C.T. Kingship and Justice: Reflections of an Italian Gothic Sculpture. Arte Medievale. Periodico internazionale di critica dell’arte medievale 2005, 4/1, 91–108.

- Francisci Pipini. Chronicon. In Rerum Italicarum Scriptores; Muratori, L.A., Ed.; Tipografia della Società Palatina: Milano, Italy, 1726; Volume 9, pp. 581–752.

- Zabbia, M. Pipino, Francesco. In Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2015; Volume 84, ad vocem.

- Delle Donne, F. Una costellazione di informazioni cronachistiche. Francesco Pipino, Riccobaldo da Ferrara, codice Fitalia e Cronica Sicilie. Bullettino dell’Istituto storico italiano per il Medio Evo 2016, 118, 157–178.

- Vitolo, G. Progettualità e territorio nel Regno svevo di Sicilia: il ruolo di Napoli. Studi Storici. Rivista trimestrale dell’Istituto Gramsci 1996, 37/2, 405–424.

- Vitolo, G. Napoli. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 2, ad vocem.

- Pasciuta, B. Compalatius. In Enciclopedia fridericiana; Zecchino, O., Ed.; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2005; Volume 1, ad vocem.

- Pistilli, P.F. Castelli normanni e svevi in Terra di Lavoro. Insediamenti fortificati in un territorio di confine; Libro Co. Italia: San Casciano in Val di Pesa, Italy, 2003.