Concrete as a construction material is extensively used in the construction industry, with global annual consumption of approximately 25 billion cubic meters. Such high usage is due to the concrete’s low cost, excellent durability, readily availability of the constituent materials, and capability to be molded into different shapes. Among different constituents of concrete, binder materials are highly important for development of hydration in the microstructure of the concrete.

- alkali-activated material

- fly ash

- short-term strengths

- pozzolanic

- properties

- utilizations

1. Introduction

Typically, cement is utilized as a binder in the formation of concrete [2]. It was reported that about 1 ton of CO 2 is released to the atmosphere for the production of one ton of OPC. It was also reported that annually OPC production releases about 1.5 billion tons of CO 2 globally, which is corresponding to about 9% of the worldwide total CO 2 emission globally [5,6,7]. For resolving this global environmental issue of cement production, numerous studies have been performed to find out a sustainable and eco-friendly supplementary cementitious material (SCM) as an alternative to cement in concrete production [8,9,10].

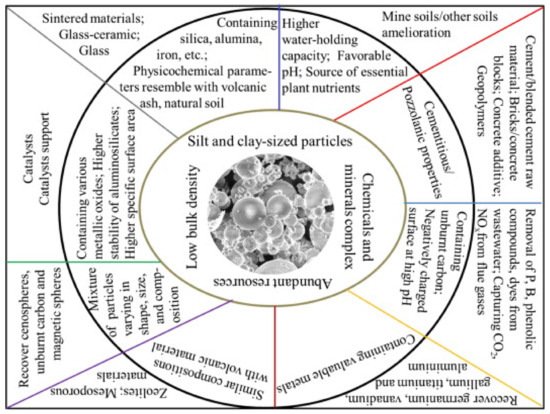

Among different SCMs used in concrete production, fly ash (FA) an industrial by-product of mineral coal burning made up from fine fuel particles found from flue gases and coal-fired boilers, and it can be employed as an SCM to minimize cement usage in concrete for lowering CO 2 emissions [8,11,12,13,14,15]. It was reported that more than about 544 million tons of FA are produced annually around the world and 80% of them are discarded in landfill. Moreover, FA has been well known as an eco-friendly material because its utilization reduces carbon footprint of cement production ( Figure 1 ). Using FA at very high content in self-consolidating concrete and high-performance concrete remained limited and further research on the topic is highly needed. Recently, substantial effort has been exerted to develop eco-efficient cement concrete composites [16,17]. FA is called pulverized fuel ash in the UK [18]. The hopper from where the FAs are collected affects their properties, and stockiest interviews showed that the cost of FAs had been already increased by 85–100% in 2012–2016 due to less availability of FA [19]. Despite that, over 6.6 × 10 7 and 11.1 × 10 7 tons of FA are generated due to coal-burning for electric power production in the United States and India every year (for example, occupying 26,304 hectares of land in India), respectively. Most FA ends up in landfill or surface impoundments as solid waste, and adequate disposal has been becoming a severe problem. Endeavors to reuse FA wastes were moderately successful, with only about 42% of FA waste being reduced [20,21,22]. Under such a condition, utilizing FA in green application technologies is necessary.

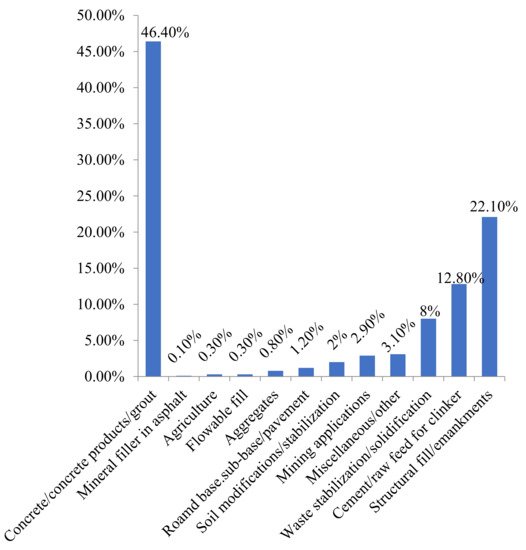

Recently, substantial efforts have been performed to improve the manufacturing of sustainable cement and the performance of FA-based alkali-activated material (AAM) [16,17]. FA is commonly employed as a pozzolanic material. It is also often employed as OPC’s partial or whole replacement material in concrete production [24]. Endeavors to reuse FA squanders were relatively successful, with about 70% of the total waste being reduced [20,21]. Figure 2 shows the worldwide production and utilization of FA [23]. FA together with other pozzolans is broadly approved by many design codes for utilization as an SCM in concrete, with an FA content of about 55%, according to CEM IV in BS EN 197 [25]. In recent years, researchers have assessed the probability of mixing diverse sorts of wastes with FA [26,27,28,29,30].

In many nations, the construction sector demands an increase in the production of SCMs, like FA, because of their role in dropping the CO 2 emissions caused by cement production. Focus has turned to produce eco-friendly concrete that utilizes by-product materials such as FA ( Figure 3 ) [31,32,33]. An eco-efficient concrete is developed with the use of FA with numerous advantages, which as early strength gaining, low utilization of natural resources, and the ability to configure into different structural elements and to stay flawless for expanded periods without fix works. Therefore, the manufacturing of eco-friendly and economical concrete composite by waste materials received significant interest all around the world. Furthermore, this study presents a review of the classifications, sources, chemical composition, production techniques, curing regimes, and clean production of FA. Subsequently, physical, fresh, and mechanical properties of FA-based concrete are investigated. The aim of this study is to help in better understanding of the behavior of FA-based concrete as a sustainable and eco-friendly material used in construction and building industries.

2. Typical Curing Regimes of Fly Ash-Based Concrete

The typical curing regimes (water and steam curing) are given in detail in this section to help understanding the impact of curing on the hardened state of FA-based concrete.

Curing protects concrete from evaporation, temperature extremes, and the negative influence of cement hydration [77]. Fresh concrete must have adequate water content for hydration process to gain potential strength, improve durability performance, and maintain chemical reactions at a rapid and continuous rate [78]. After concrete casting, each test specimen must be stored in the casting room at approximately 30 °C to be later demolded after 24 h for water curing [112]. In water curing, sufficient time is given and the concrete gains its strength rapidly between 3 and 7 days; thereby, achieving the desired strength prescribed in design codes [82]. Curing time and temperature are the most influential factors in FA-based AAM’s compressive strength. However, Adam [113] stated that AAM could solidify quickly at room temperature and exhibited compressive strength of at least 20 MPa after 4.5 h at 20 °C and approximately 70–100 MPa after 28 days. A group of researchers performed tests on AAM mortars and found that the maximum strength of FA-based AAM is achieved in the first two days of curing [114]. Reportedly, elevated temperature curing enhances the strength by removing water from the FA-based AAM; thereby, initiating the failure of capillary pores in a dense structure [115]. FA-based AAM could be remedied at room temperature, but its strength grows gradually and continuously, and thereby, requires extended curing time [116]. Nasvi et al. [117] discovered that the crack initiation thresholds and crack closure of FA-based AAM cured at high temperatures (60 °C–80 °C) were higher (30–60%) than those remedied at air temperature (23 °C and 40 °C). Nonetheless, sustained curing at elevated temperatures disrupted AAMs’ rough composition, causing dehydration and extreme shrinkage and lowering the desired strength [118].

Steam curing is a standard heating method by transmitting heat to the FA-based AAM paste through steam. The heating varies and requires an extended time to achieve the desired temperature. Microwave heating depends on the inner energy debauchery related to molecular dipoles excitation in electromagnetic fields and conveys quick and constant heat [119]. In steam curing, concrete is permitted to dry in the air with strength of about 50% of that of moist-cured concrete after water curing for 28 days from casting [77,78,112]. The test can be performed in line with BS 1881: Part 110 [120]. The AAM that is cured in the absence of high heat can be utilized in other areas beyond precast members [121]. Manesh et al. [122] prepared FA-based AAM pastes with sodium silicate ( Na 2SiO 3) solution and 10 mol/L sodium hydroxide (NaOH) remedied for 5 min below 90 W microwave radiation by further heating at 65 °C (6 h), and compared the compressive strength with FA-based AAM cured at 65 °C (24 h). Radiation of microwave creates dense microstructure, accelerates the FA dissolution in an alkali solution, and reduces the curing time [123]. Moreover, AAM can attain higher compressive strengths through oven curing compared to that of ambient curing [124].

3. Mechanical Properties

Table 10 presents the field measurement data of concrete produced with OPC and FA. The strength of FA-based AAM depends on curing condition, Si/Al ratio, alkali solution, calcium content, and various additives [5,216,217]. As FA initially reacts with liquid at a reasonably slow rate, the compressive strength of the concrete at the first few days after mixing is low; however, high strength is developed at the longer ages [218,219]. The size of the FA particles is important for the strength development of concrete. In long periods, the strength increases with FA up to a replacement rate of about 25–35%, after which the strength starts to decrease with more added FA. Generally, class C FA is used within 15–40% of the total binder of concrete. Class C FAs improves the strength if the replacement level is restricted to 25% by the mass of the binder.

As well as its brittle nature, concrete is well known for its weakness in tension. The splitting tensile strength of FA-based AAMs can be enhanced using additives, such as sweet sorghum fibers and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers together with N-carboxymethyl chitosan [133]. A group of researchers made AAM with FA and alkali-pretreated sweet sorghum fibers that were acquired from the wastage of bagasse after removing the juice from the sweet sorghum stubbles for ethanol production [245]. They reported that when the percentage of sweet sorghum fibers was 2%, the tensile strength of the AAM increased by almost 36% [245]. Adding fibers to the mixture by a certain percentage limited the increase of micro-cracks, improving the tensile strength. However, the additional increase in fiber content led to the fiber agglomeration, resulting in a rise in air foams tricked in the mixture and non-uniform fiber distribution, and decreased tensile strength. Adding cotton to an FA-based AAM exhibited a similar trend for tensile strength [246]. It was reported that the increase in the tensile strength of chitosan- and fiber-reinforced FA-based AAM was mainly due to macro-and micro-fibers that could improve hydrogen bonds, load transfer, and fiber bridge action, and reduce the micro-cracks growth and expansion.

The flexural strength of FA-based concrete is considerably improved by integrating various kinds of short artificial fibers, such as polypropylene and PVA, through a linking influence during the macro-and micro-cracking of the AAM matrix under bending. The fibers for strengthening FA-based AAM composites include PVA fiber [247], steel fiber [2,248], sweet sorghum fiber [245], and cotton fiber [249,250]. FA-based AAMs can undergo stiff failure with small tensile strength and fracture toughness [133]. To obtain a great flexural strength, 2% of PVA fiber, 2% of steel fiber, and a hybrid combination of 1% of PVA and 1% of steel fiber were added. Besides, some studies showed the deflection toughening performance of the hybrid fiber-reinforced FA and reported that the flexural and bond strengths between the AAM matrix and PVA fiber were greater than those with cement paste matrix. The AAM matrix’s alkalinity shows no influence in the degradation of steel and PVA fibers [133]. Furthermore, cotton fabric layers were also included in the FA-based AAM composite to increase the flexural strength of the composite [249,250]. The improved flexural strength was exhibited in FA-based AAM in the range of 8.2 and 31.7 MPa, while the cotton fiber content was raised from 0 to 8.3%. Furthermore, FA’s flexural strength is disturbed by the alignment of cotton fabric layers [133]. The great flexural strength of FA-based concrete reinforced with cotton fabric placed horizontally can be accredited to the enhanced load dispersal consistency within the successive cotton fabric layers. The AAM with a vertical fabric alignment endured delamination and detachments between the AAM matrix and the cotton fabric, and had a less flexural strength [250].

It has been demonstrated that the modulus of elasticity and compressive strength of FA concrete are strongly correlated [228,229]. Generally, using FA in concrete increases the elastic modulus of concrete given the FA’s pozzolanic action over the concrete’ hydration period [205]. The low modulus of FA-based concrete is attributed to the low early strength development of the concrete [213]. AAMs with the average density of 2350 kg/m 3 have a higher elastic modulus than those containing OPC [251].

4. Heat of Hydration

The heat evolution upon complete hydration of a particular amount of unhydrated cement at a given temperature is a property of FA-based concrete ( Table 12 ) [5]. The total volume of free heat and the quantities of heat delivered by a single hydrating compound can be considered as reactivity indicators. Besides, heat of hydration exemplifies the settling and toughening behavior of cement pastes and forecasts the temperature increment [77,78]. The concrete temperature due to hydration is mainly governed by the mix and material properties and ecological factors [78,255]. In terms of using FA, FA affects cement hydration rate, as indicated by the hydration concept. An opposing effect of FAs on hydration kinetics was observed because of differences in their chemical composition. For instance, the effect of Class C FA on hydration is variable, while Class F FAs decrease the hydration. Previous research has revealed that hydrating clinker phases were improved when FA is available within the first hydration days [256,257].

Furthermore, FA particles exhibit a similar phenomenon to the glass. It was illustrated that glass particles were shielded with fibrous hydrates layer, signifying C-S-H’s propensity to nucleate on glass surfaces. In addition, the C-S-H formed from hydrating FA cement pastes is comparable to the cement substitution by metakaolin and slag, with a high surface area and a foil-like morphology [258]. The CaO/SiO 2 ratio of the C-S-H produced in mixes containing FA was less than those in mixes with cement [68].

The total heat produced by hydration of OPC and mixed pastes with FA in 2 days is shown in Figure 15 [130]. As shown in the figure, the total heat emitted during the hydration of mixed pastes was lower than that of OPC paste. With an increase in the amount of FA, the amount of hydration heat decreased, which was attributed to the combined impact of the increased FA content and diluting OPC [259].

Summary of Ca-based and Na/K-based activators in FA concrete.

5. Utilizations of FA

6. Conclusions

- –

-

The manufacturing and improvement of the performance of FA-based AAM must be controlled, and the reaction aspects of the material should be studied in detail. To this end, several facets, for instance, kinetics, thermodynamics, sympathies of intermediates and perceptions into their systems, and the grades to which the Si-O-Al are polymerized and oligomerized, should be studied. These will develop progressively improved performance of the concrete when the extra additives or components are involved. However, further research is needed to confirm that the manufacturing–structure–behaviors correspondence is accurate.

- –

-

The majority of FA-based AAMs are stiff and susceptible to cracking. This performance obliges restrictions in applications and influences the long-term durability of AAMs. Therefore, innovations in the preparation must be applied to produce improved FA-based AAM composites.

- –

-

Currently, FA-based AAMs are only formed at the research laboratory scale with empirical formulations. Thus, several studies on FA-based AAM production are required and must endeavor to adopt FA-based AAMs on a large scale.

- –

-

The performance of FA-based AAMs for immobilization, toxic metal adsorption and the sealing of CO2 remained unsatisfactory. However, shifting the guidelines for preparation is worthy of further investigation.

- –

-

As an alternative material to conventional concrete, FA-based AAM may be endowed with unique properties or additional functionalities. Therefore, novel applications of FA-based AAMs are worth discovering. For example, FA-based AAMs with biomass can be approved as new light-weight and incombustible materials.

- –

-

The potential use of FA in producing high-strength and self-consolidating concretes must be studied.

- –

-

Fibers must be used to increase the strength and longevity of FA in the concrete hardened state.

- –

-

The use of FA in the design of eco-friendly buildings and cities should be highlighted.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ma14154264