Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

More than 150 cities around the world have expanded emergency cycling and walking infrastructure to increase their resilience in the face of the COVID 19 pandemic. This tendency toward walking has led it to becoming the predominant daily mode of transport that also contributes to significant changes in the relationships between the hierarchy of walking needs and walking behaviour. These changes need to be addressed in order to increase the resilience of walking environments in the face of such a pandemic.

- COVID-19

- resilience

- walking behaviour

- hierarchy of walking needs

- built environment

1. Introduction

Resilience refers to a system’s ability to efficiently absorb shocks [1]. The recent pandemic of COVID-19 has influenced many aspects of our daily life. It has meant various changes to the physical and social arrangements of our cities in order to increase urban resilience in the face of this pandemic. In regard to urban transport, in many cities, the provision of public space and infrastructure for the development of active travel-including walking and cycling-has been adopted as the main approach to increase urban resilience in the face of this pandemic [1]. These active transport modes, especially walking, are the most sustainable modes of transport. More than 150 cities have expanded emergency cycling and walking infrastructures as of late April 2020 [2]. Many cities such as Auckland, Barcelona, Bogota, New York, Quito and Rome, have been aiming to improve city infrastructure to facilitate socially distanced walking and cycling and other cities such as Montreal, Oakland, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco and Vienna are trying to create slow/safe street networks that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists and limit car access [2]. For instance, re-timing traffic lights was adopted in Brussels to give more time for pedestrians and cyclists and avoid crowding at junctions [2].

Although, as of mid-2021, it is yet unclear the duration of this pandemic, it seems that this approach toward active travel, and especially walking, is, from a long-term point of view, due to the high expense invested in this area in many cities. Walking is the cheapest and most sustainable mode of transport. This tendency of policy makers as well as inhabitants toward walking, has led to it becoming the predominant mode of transport in daily trips for many people. In regard to the relationship between the walking behaviour of citizens and their walking needs, there are five levels of needs that are considered within the walking decision-making process. These needs progress from the most basic need, feasibility (related to personal limitations), to higher-order needs (related to urban landscape) that include accessibility, safety, comfort, and pleasure, respectively [3]. Within this hierarchical structure, an individual would not typically consider a higher-order need in his or her decision to walk if a more basic need was not already satisfied [3].

Due to the situation imposed by COVID-19, since people may choose more often to walk rather than use other modes of transport, the more basic needs of walking such as accessibility and safety may play a more substantial role in the decision to walk when compared with the situation before the pandemic. Consequently, the relationship between choosing to walk and the hierarchy of walking needs may also be changed substantially. Moreover, in addition to choosing to walk and walking behaviour, walkability is the other relevant term in regard to walking patterns in the relevant studies. The walkability of a neighbourhood generally refers to the extent to which that neighbourhood provides adequate conditions for walking [4] and previous studies have used different compositions of built environmental attributes to measure the walkability index [5][6][7][8][9]. The current situation with regard to COVID-19, meaning that more basic walking needs may play a more important role in the daily walking patterns of inhabitants, may also lead to the need to re-examine and re-define the walkability of our neighbourhoods.

These changes in the relationship between the hierarchy of walking needs and walking behaviour, due to the situation imposed by COVID-19 need to be addressed. A recognition of these changes should lead to the improvement of walkability as well as walking behaviour during and after COVID-19 which will ultimately contribute to increase the resiliency of walking environments in the face of such a pandemic. The question raised in this regard is how to improve walking behaviour in relation to different levels in the hierarchy of walking needs regarding the current situation imposed by COVID-19. The next section tries to answer this question through considering the interrelationships between the different aspects concerning walking-imposed by this pandemic- and different levels in the hierarchy of walking needs.

2. The Interrelationships between Different Aspects Related to Walking in the Context of the Pandemic and Different Levels in the Hierarchy of Walking Needs

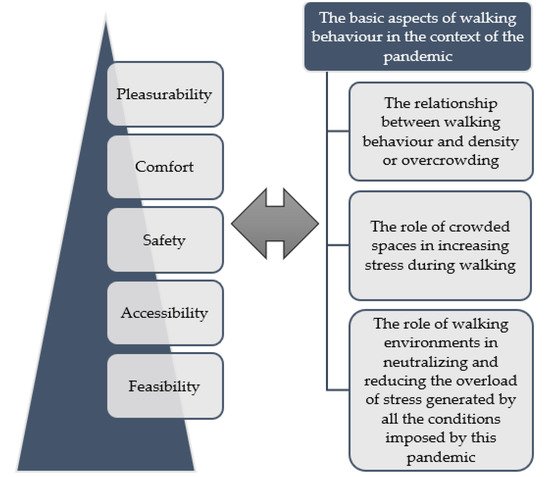

To answer the question of this study, there is a need to recognize the basic aspects of walking behaviour in the context of the pandemic. In this regard, the first aspect is the relationship between walking behaviour and density or overcrowding—as one of the main factors related to walking behaviour during this pandemic—in order to maintain physical distance and thus physical health. The second aspect is the role of crowded spaces in increasing stress during walking which in turn contributes towards mental health disorders of citizens. The third aspect is the role of walking environments in neutralizing and reducing the overload of stress generated by all the conditions imposed by this pandemic and which therefore contributes to enhancing the mental health of citizens as well.

The following subsections focus on these aspects and their interrelationships with different levels in the hierarchy of walking needs in order to address the new requirements for the improvement of walking behaviour in the context of the pandemic (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Interrelationship between different aspects of walking in the context of the pandemic and different levels of the hierarchy of walking needs.

The first subsection focuses on the influence of density and crowding on the level of contagion and stress. This subsection considers the main concepts of psychological stress theory—including primary appraisal and coping—and their relationships with the main concepts raised from the studies on crowding.

The second subsection considers and discusses the interrelationships between comfort—as one of the levels in the hierarchy of walking needs—and the stress caused by crowded spaces. In this subsection, first, the main factors in regard to creating and increasing the sense of comfort during walking are introduced. Then, the changes related to the influence of these factors on the sense of comfort made by this pandemic—from the empirical and theoretical standpoints—are discussed.

The third subsection reviews a major debate in regard to the relationship between urban configuration and insecurity—as the other level in the hierarchy of walking needs—due to the similarity found between unsafe public places before this pandemic and crowded spaces during this pandemic. In this regard, two opposing concepts of designing public spaces in relation to the security and fear of crime are introduced and discussed. In addition, the contribution of urban land use patterns to the relationship between the type of urban configuration and level of the contagion as well as stress are considered. Additionally, the role of theory of urban fabrics in this process is discussed.

The next subsection reviews which environmental factors along the pathways contribute to the neutralization and reduction in stress caused by current conditions in the context of the pandemic. Accordingly, the role of pleasurability—as the last categorization of walking needs—and its contributing factors in reducing stress during walking is discussed. Then, special attention is given to the natural environments and urban greenery as the main motivational/restorative physical factors during walking. In this regard, the main theories, including “psycho-physiological stress reduction theory” and “Attention Restoration Theory”, considering the restorative impacts of greenery and natural environments during walking, are reviewed. In addition, the role of social-related factors—as a part of the motivational/restorative factors during walking—in reducing stress, especially for elderly people, is considered as well.

Finally, since walking trips include consecutive visual sequences, the interrelationships between visual as well as aesthetic factors along these pathways, as well as consecutive visual sequences, through relevant urban design theories including “urban picturesque theory” and “prospect-refuge theory” are discussed.

3. Hierarchy of Walking Needs and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Through the current situation imposed by this pandemic, the relationship between patterns of walking behaviour with different levels in the hierarchy of walking has changed substantially. These changes need to be addressed. Recognition of these changes leads to the improvement of walkability as well as walking behaviour both during and outside of COVID-19, which will finally contribute to more resilient cities in terms of walking behaviour in the face of such a pandemic. This study was designed as a theoretical and empirical literature review seeking to improve the walking behaviour in relation to the hierarchy of walking needs within the current context of COVID-19. In this regard, three aspects were recognized as the basic aspects relevant to walking behaviour imposed by this pandemic. Next, the interrelationships between these aspects and different levels in the hierarchy of walking needs were considered and discussed in order to address the new requirements for improvements in walking behaviour in the situations imposed by this pandemic.

In regard to density as well as crowding, it was explained that contagion risk increases with crowding and not people density in public spaces. Moreover, respecting the impact of crowded spaces on the formation of stress, the two primary factors of perceived crowding and perceived control were introduced. Furthermore, the purpose of the walking trips—whether for transport or recreation—was also introduced as a factor that should be considered by future relevant studies.

Regarding the impact of sense of comfort—as one of the levels in the hierarchy of walking needs—upon stress and walking behaviour, it was shown that there is a high convergence between the factors: expected number of interactions in crowded spaces, sense of comfort/discomfort and level of stress when faced with crowded spaces during this pandemic. Furthermore, due to the notable changes in comfortable physical distance due to this pandemic, new empirical studies are required in each context to understand the actual adopted physical distance as well as the comfortable physical distance of pedestrians. It was also found that the deviation from the shortest path to the destination has been previously presented as a source of generation of discomfort as well as stress in micro scale walking environments. Thus, the role of deviation from the shortest path to destination on the generation of stress should also be considered in future empirical studies on walking in micro scale crowded spaces.

In regard to the relationship between crowded spaces and insecurity—as the other level in the hierarchy of walking needs—it was stated that the role of these crowded spaces in increasing contagion as well as stress is similar to the role of insecure public places before this pandemic in increasing the level of insecurity, fear of crime and stress. Previous studies on crime and fear of crime in the urban environment have tried to clarify the relationship between the level of crime and fear of crime with urban configuration. The relationship between urban configuration and the level of contagion as well as stress also needs to be addressed in light of the pandemic. In this regard a major debate on the relationship between type of urban configuration and crime rate was reviewed. This debate is on the impact of type of urban configuration whether permeable or defensible on level of crime as well as fear of crime. It was shown that a similar debate exists on the relationship between the type of urban configuration and the level of contagion as well as stress in the situations imposed by this pandemic. Further studies are required to clarify which type of urban configuration would contribute to less contagion and less stress in different urban sectors of each city.

Furthermore, motivational/restorative factors during walking may play a significant role in neutralizing and reducing the stress overload of inhabitants and enhancing their mental health during this pandemic. Most of the motivational/restorative factors during walking are those related to pleasurability—as one of the levels in the hierarchy of walking needs—which includes physical and social motivational factors during walking. Among the motivational/restorative physical factors during walking, natural environments as well as urban greenery have a notable impact on reducing stress and improving mental health. In this regard, the relevant theories were reviewed which support the restorative and mental health impact of natural elements and greenery on pedestrians during walking. Furthermore, the motivational/restorative factors during walking also include social factors and there is a well-known protective effect of social relationships on health and wellbeing, while social isolation is a known predictor of mortality. Such social factors are of particular importance for the mental health of inhabitants especially older people during this pandemic. Additionally, elderly people are the most vulnerable group in regard to COVID-19. However, the pandemic has adversely affected these social relations. In this regard the solutions to reviving the role of these social motivational factors at the time of the pandemic are to strengthen the possibility of passive engagement rather than active engagement with the environment and/or to reinforce the presence of motivational/restorative physical factors in walking environments instead of motivational social factors.

Finally, it was stated that walking is a movement and is different from stationary activities. Therefore, the effect of motivational/restorative factors on health as well as patterns of walking behaviour depends on the effect of compositions of these factors within consecutive visual sequences during walking. In this regard, the respected theories in urban design were reviewed. Additionally, it was shown that considering the situation imposed by COVID-19, it is more necessary to reduce concealment and increase visual connectivity among the continuous visual sequences during walking. This is in order to increase controllability as well as perceived control of pedestrians during their walking trips, which is the important factor during walking at the time of this pandemic.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph18147461

References

- Litman, T. Pandemic-Resilient Community Planning: Practical Ways to Help Communities Prepare for, Respond to, and Recover from Pandemics and Other Economic, Social and Environmental Shocks, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- International Transport Forum. Covid-19 Transport Brief: Re-Spacing our Cities for Resilience, Analysis, Factors and Figures for Transport’s Response to the Coronavirus. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Alfonzo, M. To Walk or Not to Walk? The Hierarchy of Walking Needs. Environ. Behav. 2005, 37, 808–836.

- Litman, T. Economic Value of Walkability. World Transp. Policy Pract. 2004, 10, 5–14.

- Craig, C.L.; Brownson, R.C.; Cragg, S.E.; Dunn, A.L. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity: A study examining walking to work. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23, 36–43.

- Freeman, L.; Neckerman, K.; Schwartz-Soicher, O.; Quinn, J.; Richards, C.; Bader, M.; Lovasi, G.; Jack, D.; Weiss, C.; Konty, K.; et al. Neighborhood Walkability and Active Travel (Walking and Cycling) in New York City. J. Urban Health Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med. 2012, 90.

- Jack, E.; McCormack, G.R. The associations between objectively-determined and self-reported urban form characteristics and neighborhood-based walking in adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 71.

- Kerr, J.; Emond, J.A.; Badland, H.; Reis, R.; Sarmiento, O.; Carlson, J.; Natarajan, L. Perceived Neighborhood Environmental Attributes Associated with Walking and Cycling for Transport among Adult Residents of 17 Cities in 12 Countries: The IPEN Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 290–298.

- Saelens, B.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.; Chen, D. Preliminary evaluation of neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environmental scale evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1152–1158.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!