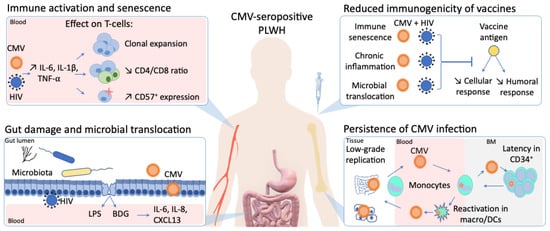

In stark contrast to the rapid development of vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), an effective human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine is still lacking. Furthermore, despite virologic suppression and CD4 T-cell count normalization with antiretroviral therapy (ART), people living with HIV (PLWH) still exhibit increased morbidity and mortality compared to the general population. Such differences in health outcomes are related to higher risk behaviors, but also to HIV-related immune activation and viral coinfections. Among these coinfections, cytomegalovirus (CMV) latent infection is a well-known inducer of long-term immune dysregulation. Cytomegalovirus contributes to the persistent immune activation in PLWH receiving ART by directly skewing immune response toward itself, and by increasing immune activation through modification of the gut microbiota and microbial translocation. In addition, through induction of immunosenescence, CMV has been associated with a decreased response to infections and vaccines.

- HIV

- cytomegalovirus

- CMV

- vaccine

- immunosenescence

- immune activation

- gut inflammation

1. Introduction

2. CMV as a Perturbator of Gut Barrier and Microbiota in People Living with HIV (PLWH)

2.1. Gut as a Viral Sanctuary

2.2. Gut Damage and Microbial Translocation

2.3. Gut Microbiota

3. Impact of CMV Infection on Response to Pathogens and Vaccines

4. CMV as a Catalyzer of Immune Activation and Altered Response to Vaccine in PLWH

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/v13071266

References

- Ghosn, J.; Taiwo, B.; Seedat, S.; Autran, B.; Katlama, C. HIV. Lancet 2018, 392, 685–697.

- AIDSinfo | UNAIDS. Available online: (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Neurath, M.F.; Überla, K.; Ng, S.C. Gut as Viral Reservoir: Lessons from Gut Viromes, HIV and COVID-19. Gut 2021.

- Lapenta, C.; Boirivant, M.; Marini, M.; Santini, S.M.; Logozzi, M.; Viora, M.; Belardelli, F.; Fais, S. Human Intestinal Lamina Propria Lymphocytes Are Naturally Permissive to HIV-1 Infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999, 29, 1202–1208.

- Brenchley, J.M.; Price, D.A.; Schacker, T.W.; Asher, T.E.; Silvestri, G.; Rao, S.; Kazzaz, Z.; Bornstein, E.; Lambotte, O.; Altmann, D.; et al. Microbial Translocation Is a Cause of Systemic Immune Activation in Chronic HIV Infection. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1365–1371.

- Isnard, S.; Lin, J.; Fombuena, B.; Ouyang, J.; Varin, T.V.; Richard, C.; Marette, A.; Ramendra, R.; Planas, D.; Raymond Marchand, L.; et al. Repurposing Metformin in Nondiabetic People With HIV: Influence on Weight and Gut Microbiota. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa338.

- Ancona, G.; Merlini, E.; Tincati, C.; Barassi, A.; Calcagno, A.; Augello, M.; Bono, V.; Bai, F.; Cannizzo, E.S.; d’Arminio Monforte, A.; et al. Long-Term Suppressive CART Is Not Sufficient to Restore Intestinal Permeability and Gut Microbiota Compositional Changes. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 639291.

- Serrano-Villar, S.; Sainz, T.; Lee, S.A.; Hunt, P.W.; Sinclair, E.; Shacklett, B.L.; Ferre, A.L.; Hayes, T.L.; Somsouk, M.; Hsue, P.Y.; et al. HIV-Infected Individuals with Low CD4/CD8 Ratio despite Effective Antiretroviral Therapy Exhibit Altered T Cell Subsets, Heightened CD8+ T Cell Activation, and Increased Risk of Non-AIDS Morbidity and Mortality. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004078.

- Fletcher, C.V.; Staskus, K.; Wietgrefe, S.W.; Rothenberger, M.; Reilly, C.; Chipman, J.G.; Beilman, G.J.; Khoruts, A.; Thorkelson, A.; Schmidt, T.E.; et al. Persistent HIV-1 Replication Is Associated with Lower Antiretroviral Drug Concentrations in Lymphatic Tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2307–2312.

- Maidji, E.; Somsouk, M.; Rivera, J.M.; Hunt, P.W.; Stoddart, C.A. Replication of CMV in the Gut of HIV-Infected Individuals and Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006202.

- Gordon, C.L.; Miron, M.; Thome, J.J.C.; Matsuoka, N.; Weiner, J.; Rak, M.A.; Igarashi, S.; Granot, T.; Lerner, H.; Goodrum, F.; et al. Tissue Reservoirs of Antiviral T Cell Immunity in Persistent Human CMV Infection. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 651–667.

- Gianella, S.; Chaillon, A.; Mutlu, E.A.; Engen, P.A.; Voigt, R.M.; Keshavarzian, A.; Losurdo, J.; Chakradeo, P.; Lada, S.M.; Nakazawa, M.; et al. Effect of Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr Virus Replication on Intestinal Mucosal Gene Expression and Microbiome Composition of HIV-Infected and Uninfected Individuals. AIDS 2017, 31, 2059–2067.

- Routy, J.-P.; Mehraj, V. Potential Contribution of Gut Microbiota and Systemic Inflammation on HIV Vaccine Effectiveness and Vaccine Design. AIDS Res. Ther 2017, 14, 48.

- Isnard, S.; Lin, J.; Bu, S.; Fombuena, B.; Royston, L.; Routy, J.-P. Gut Leakage of Fungal-Related Products: Turning Up the Heat for HIV Infection. Front. Immunol 2021, 12, 656414.

- Sankaran, S.; George, M.D.; Reay, E.; Guadalupe, M.; Flamm, J.; Prindiville, T.; Dandekar, S. Rapid Onset of Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction in Primary Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Is Driven by an Imbalance between Immune Response and Mucosal Repair and Regeneration. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 538–545.

- Hensley-McBain, T.; Berard, A.R.; Manuzak, J.A.; Miller, C.J.; Zevin, A.S.; Polacino, P.; Gile, J.; Agricola, B.; Cameron, M.; Hu, S.-L.; et al. Intestinal Damage Precedes Mucosal Immune Dysfunction in SIV Infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2018, 11, 1429–1440.

- Nazli, A.; Chan, O.; Dobson-Belaire, W.N.; Ouellet, M.; Tremblay, M.J.; Gray-Owen, S.D.; Arsenault, A.L.; Kaushic, C. Exposure to HIV-1 Directly Impairs Mucosal Epithelial Barrier Integrity Allowing Microbial Translocation. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000852.

- Allam, O.; Samarani, S.; Mehraj, V.; Jenabian, M.-A.; Tremblay, C.; Routy, J.-P.; Amre, D.; Ahmad, A. HIV Induces Production of IL-18 from Intestinal Epithelial Cells That Increases Intestinal Permeability and Microbial Translocation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194185.

- Ramendra, R.; Isnard, S.; Lin, J.; Fombuena, B.; Ouyang, J.; Mehraj, V.; Zhang, Y.; Finkelman, M.; Costiniuk, C.; Lebouché, B.; et al. CMV Seropositivity Is Associated with Increased Microbial Translocation in People Living with HIV and Uninfected Controls. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019.

- Schretter, C.E. Links between the Gut Microbiota, Metabolism, and Host Behavior. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 245–248.

- Tibbs, T.N.; Lopez, L.R.; Arthur, J.C. The Influence of the Microbiota on Immune Development, Chronic Inflammation, and Cancer in the Context of Aging. Microb. Cell 2019, 6, 324–334.

- Ouyang, J.; Lin, J.; Isnard, S.; Fombuena, B.; Peng, X.; Marette, A.; Routy, B.; Messaoudene, M.; Chen, Y.; Routy, J.-P. The Bacterium Akkermansia Muciniphila: A Sentinel for Gut Permeability and Its Relevance to HIV-Related Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11.

- Rooks, M.G.; Garrett, W.S. Gut Microbiota, Metabolites and Host Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 341–352.

- Kim, C.H. Control of Lymphocyte Functions by Gut Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1161–1171.

- Abt, M.C.; Osborne, L.C.; Monticelli, L.A.; Doering, T.A.; Alenghat, T.; Sonnenberg, G.F.; Paley, M.A.; Antenus, M.; Williams, K.L.; Erikson, J.; et al. Commensal Bacteria Calibrate the Activation Threshold of Innate Antiviral Immunity. Immunity 2012, 37, 158–170.

- Mudd, J.C.; Brenchley, J.M. Gut Mucosal Barrier Dysfunction, Microbial Dysbiosis, and Their Role in HIV-1 Disease Progression. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214 (Suppl. 2), S58–S66.

- Dillon, S.M.; Lee, E.J.; Kotter, C.V.; Austin, G.L.; Dong, Z.; Hecht, D.K.; Gianella, S.; Siewe, B.; Smith, D.M.; Landay, A.L.; et al. An Altered Intestinal Mucosal Microbiome in HIV-1 Infection Is Associated with Mucosal and Systemic Immune Activation and Endotoxemia. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 983–994.

- Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Somsouk, M. HIV and the Gut Microbiota: Composition, Consequences, and Avenues for Amelioration. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 204–213.

- Rocafort, M.; Noguera-Julian, M.; Rivera, J.; Pastor, L.; Guillén, Y.; Langhorst, J.; Parera, M.; Mandomando, I.; Carrillo, J.; Urrea, V.; et al. Evolution of the Gut Microbiome Following Acute HIV-1 Infection. Microbiome 2019, 7, 73.

- Mutlu, E.A.; Keshavarzian, A.; Losurdo, J.; Swanson, G.; Siewe, B.; Forsyth, C.; French, A.; DeMarais, P.; Sun, Y.; Koenig, L.; et al. A Compositional Look at the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome and Immune Activation Parameters in HIV Infected Subjects. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10.

- Santos Rocha, C.; Hirao, L.A.; Weber, M.G.; Méndez-Lagares, G.; Chang, W.L.W.; Jiang, G.; Deere, J.D.; Sparger, E.E.; Roberts, J.; Barry, P.A.; et al. Subclinical Cytomegalovirus Infection Is Associated with Altered Host Immunity, Gut Microbiota, and Vaccine Responses. J. Virol. 2018, 92.

- Choi, K.H.; Basma, H.; Singh, J.; Cheng, P.-W. Activation of CMV Promoter-Controlled Glycosyltransferase and Beta -Galactosidase Glycogenes by Butyrate, Tricostatin A, and 5-Aza-2’-Deoxycytidine. Glycoconj. J. 2005, 22, 63–69.

- Gustafson, C.E.; Kim, C.; Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. Influence of Immune Aging on Vaccine Responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1309–1321.

- Goodwin, K.; Viboud, C.; Simonsen, L. Antibody Response to Influenza Vaccination in the Elderly: A Quantitative Review. Vaccine 2006, 24, 1159–1169.

- Siegrist, C.-A.; Aspinall, R. B-Cell Responses to Vaccination at the Extremes of Age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 185–194.

- Lazuardi, L.; Jenewein, B.; Wolf, A.M.; Pfister, G.; Tzankov, A.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B. Age-Related Loss of Naïve T Cells and Dysregulation of T-Cell/B-Cell Interactions in Human Lymph Nodes. Immunology 2005, 114, 37–43.

- Britanova, O.V.; Putintseva, E.V.; Shugay, M.; Merzlyak, E.M.; Turchaninova, M.A.; Staroverov, D.B.; Bolotin, D.A.; Lukyanov, S.; Bogdanova, E.A.; Mamedov, I.Z.; et al. Age-Related Decrease in TCR Repertoire Diversity Measured with Deep and Normalized Sequence Profiling. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 2689–2698.

- Cicin-Sain, L.; Brien, J.D.; Uhrlaub, J.L.; Drabig, A.; Marandu, T.F.; Nikolich-Zugich, J. Cytomegalovirus Infection Impairs Immune Responses and Accentuates T-Cell Pool Changes Observed in Mice with Aging. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002849.

- Lindau, P.; Mukherjee, R.; Gutschow, M.V.; Vignali, M.; Warren, E.H.; Riddell, S.R.; Makar, K.W.; Turtle, C.J.; Robins, H.S. Cytomegalovirus Exposure in the Elderly Does Not Reduce CD8 T Cell Repertoire Diversity. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 476–483.

- Jergović, M.; Uhrlaub, J.L.; Contreras, N.A.; Nikolich-Žugich, J. Do Cytomegalovirus-Specific Memory T Cells Interfere with New Immune Responses in Lymphoid Tissues? Geroscience 2019, 41, 155–163.

- Reese, T.A.; Bi, K.; Kambal, A.; Filali-Mouhim, A.; Beura, L.K.; Bürger, M.C.; Pulendran, B.; Sekaly, R.-P.; Jameson, S.C.; Masopust, D.; et al. Sequential Infection with Common Pathogens Promotes Human-like Immune Gene Expression and Altered Vaccine Response. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 713–719.

- Khan, N.; Hislop, A.; Gudgeon, N.; Cobbold, M.; Khanna, R.; Nayak, L.; Rickinson, A.B.; Moss, P.A.H. Herpesvirus-Specific CD8 T Cell Immunity in Old Age: Cytomegalovirus Impairs the Response to a Coresident EBV Infection. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 7481–7489.

- Derhovanessian, E.; Maier, A.B.; Hähnel, K.; McElhaney, J.E.; Slagboom, E.P.; Pawelec, G. Latent Infection with Cytomegalovirus Is Associated with Poor Memory CD4 Responses to Influenza A Core Proteins in the Elderly. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3624–3631.

- Kadambari, S.; Klenerman, P.; Pollard, A.J. Why the Elderly Appear to Be More Severely Affected by COVID-19: The Potential Role of Immunosenescence and CMV. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, 30, e2144.

- Söderberg-Nauclér, C. Does Reactivation of Cytomegalovirus Contribute to Severe COVID-19 Disease? Immun. Ageing 2021, 18, 12.

- Trzonkowski, P.; Myśliwska, J.; Szmit, E.; Wieckiewicz, J.; Lukaszuk, K.; Brydak, L.B.; Machała, M.; Myśliwski, A. Association between Cytomegalovirus Infection, Enhanced Proinflammatory Response and Low Level of Anti-Hemagglutinins during the Anti-Influenza Vaccination—An Impact of Immunosenescence. Vaccine 2003, 21, 3826–3836.

- Wald, A.; Selke, S.; Magaret, A.; Boeckh, M. Impact of Human Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection on Immune Response to Pandemic 2009 H1N1 Influenza Vaccine in Healthy Adults. J. Med. Virol. 2013, 85, 1557–1560.

- van den Berg, S.P.H.; Warmink, K.; Borghans, J.A.M.; Knol, M.J.; van Baarle, D. Effect of Latent Cytomegalovirus Infection on the Antibody Response to Influenza Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 208, 305–321.

- Bowyer, G.; Sharpe, H.; Venkatraman, N.; Ndiaye, P.B.; Wade, D.; Brenner, N.; Mentzer, A.; Mair, C.; Waterboer, T.; Lambe, T.; et al. Reduced Ebola Vaccine Responses in CMV+ Young Adults Is Associated with Expansion of CD57+KLRG1+ T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217.

- Ambrosioni, J.; Blanco, J.L.; Reyes-Urueña, J.M.; Davies, M.-A.; Sued, O.; Marcos, M.A.; Martínez, E.; Bertagnolio, S.; Alcamí, J.; Miro, J.M.; et al. Overview of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Adults Living with HIV. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e294–e305.

- Wall, N.; Godlee, A.; Geh, D.; Jones, C.; Faustini, S.; Harvey, R.; Penn, R.; Chanouzas, D.; Nightingale, P.; O’Shea, M.; et al. Latent Cytomegalovirus Infection and Previous Capsular Polysaccharide Vaccination Predict Poor Vaccine Responses in Older Adults, Independent of Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021.

- McElhaney, J.E.; Garneau, H.; Camous, X.; Dupuis, G.; Pawelec, G.; Baehl, S.; Tessier, D.; Frost, E.H.; Frasca, D.; Larbi, A.; et al. Predictors of the Antibody Response to Influenza Vaccination in Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2015, 3, e000140.

- Chanouzas, D.; Sagmeister, M.; Faustini, S.; Nightingale, P.; Richter, A.; Ferro, C.J.; Morgan, M.D.; Moss, P.; Harper, L. Subclinical Reactivation of Cytomegalovirus Drives CD4+CD28null T-Cell Expansion and Impaired Immune Response to Pneumococcal Vaccination in Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-Associated Vasculitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 234–244.

- Miles, D.J.C.; van der Sande, M.; Jeffries, D.; Kaye, S.; Ismaili, J.; Ojuola, O.; Sanneh, M.; Touray, E.S.; Waight, P.; Rowland-Jones, S.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Gambian Infants Leads to Profound CD8 T-Cell Differentiation. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5766–5776.

- Falconer, O.; Newell, M.-L.; Jones, C.E. The Effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Cytomegalovirus Infection on Infant Responses to Vaccines: A Review. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 328.

- Smith, C.; Moraka, N.O.; Ibrahim, M.; Moyo, S.; Mayondi, G.; Kammerer, B.; Leidner, J.; Gaseitsiwe, S.; Li, S.; Shapiro, R.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Exposure but Not Early Cytomegalovirus Infection Is Associated With Increased Hospitalization and Decreased Memory T-Cell Responses to Tetanus Vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1167–1175.

- Sanz-Ramos, M.; Manno, D.; Kapambwe, M.; Ndumba, I.; Musonda, K.G.; Bates, M.; Chibumbya, J.; Siame, J.; Monze, M.; Filteau, S.; et al. Reduced Poliovirus Vaccine Neutralising-Antibody Titres in Infants with Maternal HIV-Exposure. Vaccine 2013, 31, 2042–2049.

- Parmigiani, A.; Alcaide, M.L.; Freguja, R.; Pallikkuth, S.; Frasca, D.; Fischl, M.A.; Pahwa, S. Impaired Antibody Response to Influenza Vaccine in HIV-Infected and Uninfected Aging Women Is Associated with Immune Activation and Inflammation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79816.

- Pallikkuth, S.; De Armas, L.R.; Pahwa, R.; Rinaldi, S.; George, V.K.; Sanchez, C.M.; Pan, L.; Dickinson, G.; Rodriguez, A.; Fischl, M.; et al. Impact of Aging and HIV Infection on Serologic Response to Seasonal Influenza Vaccination. AIDS 2018, 32, 1085–1094.