Social distancing has been a critical public health measure for the COVID-19 pandemic, yet a long history of research strongly suggests that loneliness and social isolation play a major role in several cognitive health issues. What is the true severity and extent of risks involved and what are potential approaches to balance these competing risks? This review aimed to summarize the neurological context of social isolation and loneliness in population health and the long-term effects of social distancing as it relates to neurocognitive aging, health, and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The full scope of the underlying causal mechanisms of social isolation and loneliness in humans remains unclear partly because its study is not amenable to randomized controlled trials; however, there are many detailed experimental and observational studies that may provide a hypothesis-generating theoretical framework to better understand the pathophysiology and underlying neurobiology. To address these challenges and inform future studies, we conducted a topical review of extant literature investigating associations of social isolation and loneliness with relevant biological, cognitive, and psychosocial outcomes, and provide recommendations on how to approach the need to fill key knowledge gaps in this important area of research.

- social isolation

- cognitive health

- brain health

- loneliness

- brain aging

1. Introduction

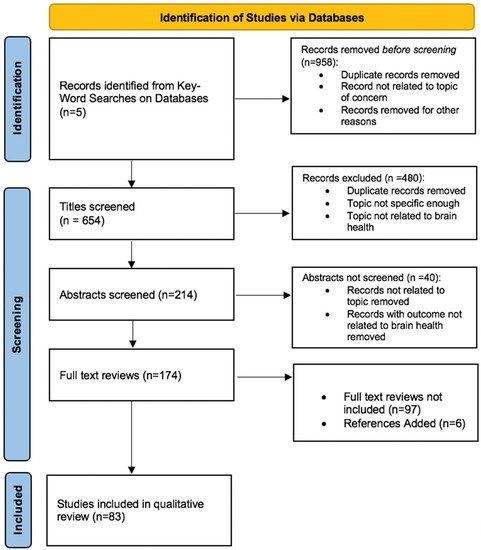

2. Study Selections

3. Biological Outcomes

3.1. Associations with Inflammation

3.2. Associations with Neuroimaging Measures

3.3. Associations with Neuropathology

3.4. Associations with Neuroplasticity

3.5. Associations with Sleep

4. Cognitive Outcomes

Associations with Cognitive Function

5. Psychosocial Outcomes

5.1. Associations with Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

5.2. Mediating and Modifying Factors

6. Future Directions

6.1. Intervention Studies

6.2. Recommendations to Address Knowledge Gaps

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph18147307