1. Introduction

Despite the long history of cancer being treated mainly by the “cut, poison and burn” principle, immunotherapeutics allowed to outsmart the tumor using the intrinsic potential of the immune system. The immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1) have been the first kind of drugs that gave patients hope and revolutionized the treatment of cancers previously thought to be incurable [1]. Since the establishment of immunotherapy approaches, dozens of immune checkpoint inhibitors were studied for the treatment of different cancers with various degrees of success [2,3]. The breakthroughs of immunotherapy had an avalanche effect and stimulated the research of multiple combinatorial approaches for cancer treatment [4,5].

The modern arsenal of immunotherapeutics is impressively rich and includes diverse drugs and approaches such as pro-inflammatory cytokines [6,7], cancer vaccines [8,9], adoptive T-cell therapies [10], antibody-based immunotherapies (bispecific T cell engagers, checkpoint inhibitors, antibody-drug conjugates) [11] and oncolytic viruses (OV) [12,13,14]. The latest is of particular interest because of the recent encouraging clinical results and extreme flexibility of virus development platforms.

The oncolytic potential of several viruses has been known for quite a while, however, its clinical application for cancer therapy has been hampered by a lack of knowledge in virus molecular biology and immune pathways [15]. Most OV show selective replication in tumor cells (have enhanced tumor tropism) and affect several key steps in cancer–immunity cycle [16]. (IFN type I response genes, tumor suppressor proteins, etc.) are dysfunctional in tumor cells, enabling preferential replication of OVs [17,18,19]. Although some viruses exhibit inherent tropism for tumor cells, genetic engineering also helps to precisely tune up the virus life cycle to become the most potent cancer killer [20,21,22,23].

The therapeutic effect of OVs in cancer therapy is mediated by several main mechanisms that eventually lead to immunogenic cell death (ICD), a form of regulated cell death (RCD) [24]. Firstly, OV infection of cancer cells initiates direct cell lysis [25,26,27,28]. OVs can induce anti-angiogenesis through reduction of VEGF concentration, resulting in a loss of tumor perfusion that leads to apoptotic and necrotic tumor cell death [26,29,30]. In particular, the lysis of tumor cells caused by oncolytic viruses leads to the release of danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as uric acid, secreted adenosine triphosphate (ATP), high mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1), surface-exposed calreticulin (ecto-CRT), heat shock proteins as well as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) including viral components (nucleic acids, proteins and capsid components).

2. Combination Therapies and Future Perspectives

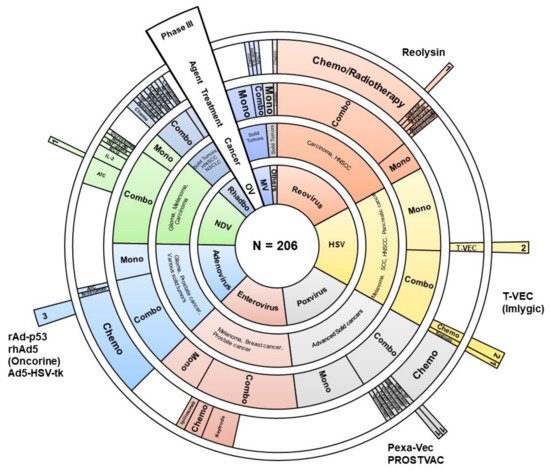

In the past few years, we have seen an unprecedented increase in clinical trials using oncolytic viruses. Here, we reviewed 206 clinical trials found in open sources (databases and publications). For 109 studies, we managed to find relevant publications describing preliminary or final results (hereinafter, see

Supplementary Material). Most of them are early-stage trial studies, with only 12 Phase III studies (

Figure 1). Results of these clinical trials point to the limited efficacy of oncolytics despite all the advantages of subverted antiviral immune response in cancer cells.

Figure 1. Graphical representation of 206 clinical trials using oncolytic viruses as immunotherapy. Sunburst diagram depicts virus genus (the inner circle), type of cancer, variants of therapy (single agent (mono) or combinatorial approach (combo), combinatorial agent (if applicable). The outer sector illustrates the drugs that have reached Phase III of clinical trials or have been registered. Chemo—chemotherapy, ATC—autologous tumor cells, HNSCC—head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, NSCLC—non-small-cell lung carcinoma, SCC—squamous cell carcinoma, BCG—Bacillus Calmette–Guérin, MSCT—mesenchymal stem cell therapy, GM-CSF—granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IL-2—interleukine-2 OV—oncolytic virus, HSV—herpes simplex virus, MV—measles virus, Rhabdo—rhabdoviruses (VSV and Maraba), NDV—Newcastle disease virus, others—Parvovirus and Seneca Valley virus.

Since oncolytic viruses can activate innate and adaptive immune mechanisms that are capable of targeting both cancer cells and viruses, it is very important to keep a balance between viral immunogenicity and anticancer immunity. One of the major causes of the limited efficacy of oncolytics observed in human trials is a pre-existing immunity against a virus. Antibodies to AAV [

204], adenovirus [

205], or enterovirus (ECHO, Coxsackievirus) are frequently found among cancer patients. According to literature among 391 healthy adults from 21 provinces and cities of China tested for the presence of antibodies 85.7%, 58.8%, and 74.2% were found to be seropositive against enterovirus 71, coxsackievirus 16, and adenovirus human serotype 5, respectively [

206]. It might be also the factor that hampers the efficacy of oncolytic HSV, since more than 67% of the population is latently infected by HSV-1 [

66].

Intriguingly, pre-existing viral immunity is not always a hurdle for immunotherapy. Several promising preclinical models using oncolytic NDV and Adenovirus have successfully demonstrated that antibodies to the virus may potentiate anti-tumor immune response by retargeting antiviral antibodies and activating tumor-directed CD8+ T-cells [

207,

208]. In addition, anti-viral immunity may be exploited further to increase the efficiency of virus cancer therapy by rationale design of recombinant bifunctional adapter carrying the tumor-specific ligand and adenovirus immunogenic domain (hexon DE1) that activates tumor microenvironment, prolongs survival of mice and, of particular importance, can be possibly used to manage metastatic cancers [

209]. Therefore, we do suggest that the pre-existing viral immunity is an important variable factor that may significantly influence the results of cancer virotherapy and should be critically accessed for a particular oncolytic virus.

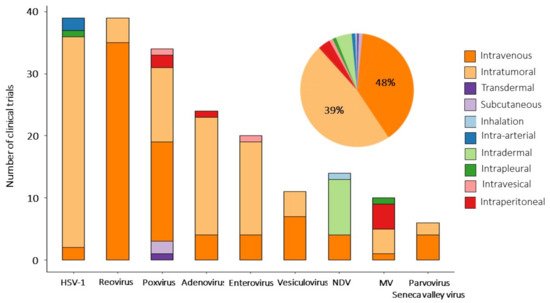

To partly overcome the issue of preexisting immunity and to improve the efficacy of virotherapy use of plasmapheresis, immunosuppressants, non-human viruses and optimal delivery routes have been extensively studied [

210]. OVs can be delivered systemically (intravenous injection) or directly (by intratumoral injection). Both delivery approaches have been applied in clinical studies, but intratumoral delivery was used predominantly. Clinical trials with H101 and talimogene laherparepvec have shown that intratumoral injections are the most effective and safe way to administer OV [

211,

212,

213]. The intratumoral injection is a route of administration in 94 clinical trials (48%) and in 77 (37%) trials OVs are delivered systemically (

Figure 2), wherein 10 studies assess the efficacy of IT vs. IV infusions (3 CTs—For VSV, 3—For poxviruses). The remaining 29 studies are exploring alternative routes of administration (intraperitoneal, intradermal, intrapleural, etc.) (see

Supplementary Material). The abscopal effect, or systemic antitumor effect, has been registered after local administration of oncolytic viruses [

214,

215,

216]. Virally induced oncolysis can promote the release of danger-associated molecular patterns that induce immune system awaking and systemic antineoplastic response. The abscopal effect can be boosted by the complementary use of oncolytics with active immunotherapeutic. For example, equivalent response rates were recorded in injected and distant tumors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated with Pexa-Vec and GM-CSF [

83]. Since not all tumor lesions are accessible for direct injection, especially in the case of metastatic disease, the systemic approach seems to be the preferable option. However, the rapid clearance of viruses from the bloodstream before they reach their targets reduces the efficacy of systemic administration [

217,

218,

219]. Additional OV modifications (genetic engineering of capsids or chemical conjugation) may significantly expand the lifetime of OV circulation after systemic administration [

213,

220]. There is a need to confirm these findings in clinical trials.

Figure 2. Routes of administration of oncolytic viruses. Bar plot shows delivery routes for every oncolytic virus used in reviewed clinical studies. The pie chart diagram summarizes the overall distribution of delivery strategies among clinical trials analyzed in this entry.

The safety of OV therapy is an imperative question that should be addressed in any clinical trial. Encouragingly, most of the studies we reviewed report the safety of virotherapy (Grade 1–2) with only a few cases of severe adverse effects (Grade 3–4). Oncolytics are well-tolerated in various settings and cancer types [

202]. An additional concern is the fact that viral infections may aggravate autoimmune conditions. It has been previously shown that B19 parvovirus may cause rheumatoid arthritis [

221], coxsackievirus—type 1 diabetes [

222]. Benefits of virotherapy may overcome potential risk for these patients; nonetheless requires careful investigation.

An additional boost is needed to counteract so-called “cold tumors” that do not respond well to immunotherapy. In this connection, the use of viruses in combination with ICI, immune-stimulating agents and chemokines (as separate agents or cloned into the OV genome) seems to be the most promising approach.

Combinatorial approaches become predominant in the treatment of cancers that are resistant to standard therapy or recurrent (117 clinical trials out of 206, 57%,

Table S1 in Supplementary Material). Among the ICI the leading position is occupied by antibodies blocking the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, which bind either to PD-1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, avelumab) or to its ligand PD-L1 (durvalumab, cemiplimab, atezolizumab, HX008) (35 clinical trials out of 44, 80%), and pembrolizumab is used in most studies (14 studies).

The second most popular agent to combine with oncolytic viruses (vaccinia virus, HSV-1 and Coxsackievirus 21) is the CTLA-4 inhibitor (ipilimumab, tremelimumab) (6 studies out of 44, 13%). CTLA-4 inhibitors block the negative regulation of T-lymphocytes (B7-CTLA4 interaction), contributing to their long-term activation. Reassuring results indicate that the combination of talimogene laherparepvec with ipilimumab has greater efficacy than either therapy alone, without additional safety concerns above those expected for both medicines in monotherapy. Thus, 38 patients with melanoma (39%) in the combination arm and 18 patients (18%) in the ipilimumab arm had an objective response, and importantly, responses were not limited to injected lesions: responses in the visceral lesion were observed in 52% of patients in the combination arm and 23% of patients in the ipilimumab arm [

3].

As for immunomodulatory agents, GM-CSF, IFN-alpha and IL-2 are most often used in combination with oncolytics (in nine clinical trials). Additional combinations of oncolytics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Viral immunotherapy in clinical applications.

| Combinatorial Agent |

n |

Function |

| Check-point inhibitors |

|

|

| Pembrolizumab |

14 |

Targets and blocks a PD-1 protein on the surface of T-cells. Blocking PD-1 triggers the T-cells activation towards finding and killing cancer cells. Pemrolizumab known under brand name Keytruda. |

| Nivolumab |

8 |

An anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (brand name Opdivo). |

| Ipililumab |

5 |

Humanized immune checkpoint inhibitor which blocks CTLA-4 receptor and upregulates cytotoxic T–lymphocytes (brand name Yervoy). |

| Avelumab |

3 |

An anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (brand name Bavencio). |

| Durvalumab |

3 |

An anti-PD-L1 specific human IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody. |

| Cemiplimab |

3 |

An anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (brand name Libtayo). |

| Atezolizumab |

2 |

An anti-PDL-1 monoclonal antibody (brand name Tecentriq). |

| Socazolimab |

1 |

Anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody (ZKAB001). |

| HX008 |

1 |

Anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody. |

| Vibostolimab |

1 |

Vibostolimab is a monoclonal antibody against T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT). Vibostolimab blocks the interaction between TIGIT and its ligands (CD112 and CD155) thereby activating T cells. |

| Bevacizumab |

1 |

Bevacizumab (Avastin) targets cellular vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a protein that is essential for blood vessel growth. |

| Trasuzumab |

1 |

Trasuzumab (Herceptin) is an anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody targeting breast cancer and stomach cancer cells expressing HER2 receptors. |

| Tremelimumab |

1 |

An anti- CTLA-4 monoclonal antibody. |

| Immunomodulatory factors |

|

|

| Interleukine-2 (IL-2) |

3 |

Stimulates cytotoxic T cells (CD8+) and NK cells, controls both the primary and secondary expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cell populations. |

| Interferon-α |

3 |

Cytokine activates immune cells (NK cells and T-cells) and suppresses tumor cell division by inhibiting protein and hormone synthesis. It also reduces angiogenesis through inhibition of angiogenic factors b-FGF and VEGF. |

| Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) |

3 |

GM-CSF enhances the number of circulating white blood cells and increases neutrophil and monocyte function. It also actively shapes the dendritic cell profile leading to an enhanced anti-tumor effect. |

| Antigens |

|

|

| Autologous tumor cells |

14 |

Therapeutic agent produced from patient tumor cells. Processed and treated tumor cells are a great source of cancer antigens that, after administration, boost the immune system of the individual that they have been isolated. |

| Melanoma-associated antigen 3(MAGE-A3) |

3 |

MAGE-A3 is a tumor-specific shared antigen often expressed in lung cancer and melanoma. Immunization with MAGE-A3 tends to stimulate the immune response to cancer, which has been traditionally considered as poorly immunogenic. |

| ag-E6E7 |

1 |

Human papillomavirus oncoproteins E6 and E7. Immunization with E6 and E7 antigens improves antitumor immunity against HPV-related tumors and enhances the immunogenicity of dendritic cells. |

| Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) |

1 |

Nontumor antigen was initially used as a tuberculosis vaccine. High immunogenic BCG mounts an overall immune response that potentially decreases the reoccurrence of cancer. |

| Radiotherapy/Chemotherapy/Surgery |

80 |

Various drugs, radiotherapy regimes accompanied by tumor resection (where possible) are in use in combination with virotherapy. The reader may find specific details in decent reviews and supplementary materials. |

| Single-agent virotherapy |

88 |

Wild-type viruses attenuated or genetically engineered variants armored with immunomodulatory molecules are frequently used as a monotherapy. Variants of the used genetic modifications of oncolytics (mainly for stimulating the immune system) are shown in Table 2. |

Designing novel ICI is an extremely competitive area of research. The efforts are mainly focused on overcoming de novo or acquired resistance to certain ICI. Among the most promising candidates, several new molecules are currently undergoing preclinical/clinical trials (lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), immune costimulatory molecule (ICOS) and its ligand (ICOS L) [

223,

224,

225]. In particular, the multifaceted role of ICOS/ICOS L in T-cell activation is crucial for autoimmune diseases and cancer. We foresee that cancer virotherapy in combination with novel ICI might be a new powerful tool in the next-generation cancer immunotherapy.

The most commonly used payloads in oncolytic viruses are summarized in

Table 2. The GM-CSF occupies a leading position among genes additionally integrated into the genome of oncolytic viruses (49 clinical trials, see

Supplementary Material). The main role of GM-CSF is to stimulate the proliferation, differentiation and migration of macrophages and dendritic cells. The high pro-inflammatory and regulatory potential of GM-CSF promoted its use in the treatment of a wide range of oncological diseases [

226,

227,

228,

229].

Table 2. Oncolytic viruses engineering and payloads in clinical practice.

| Payload and Modifications |

n |

Function |

| GM-CSF (CSF2) |

49 |

GM-CSF is a growth factor that stimulates differentiation, proliferation and migration of myeloid cells. |

| Thymidine kinase (TK) |

24 |

HSV-1 TK is a virulence factor deletion of which attenuates virus but is not essential for virus replication. In addition, TK is being used as a suicide gene to specifically target tumor cells. |

| Human sodium iodide symporter (hNIS) |

14 |

NIS mediates a transport process of iodide uptake. Overexpression of NIS in cancer cells increases iodide concentration within the cells that benefit from radioiodine therapy. |

| p53 (TP53) |

10 |

Tumor protein is a major tumor suppressor factor that acts through the regulation of the cell cycle. p53 often malfunctions in tumor cells. |

| Interferon β (IFN-beta) |

8 |

IFN-beta is a cytokine, which has an antiviral and anti-proliferative effect. IFN-beta stimulates innate and adaptive immunity and has confirmed antitumor activity. |

| MAGE-A3 |

3 |

Tumor-specific antigen. MAGE-A3 immunization elicits an antigen-specific immune response. |

| PSA-TRICOM (B7.1, ICAM-1, LFA-3) |

2 |

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA). B7.1, ICAM-1, LFA-3 are T-cell costimulatory molecules. |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) |

2 |

CEA is a glycoprotein, which rarely found in the blood of adults. Expression of CEA serves as a marker for noninvasive monitoring of virus dissemination in vivo. |

| Interleukine-12 (IL-12) |

1 |

IL-12 plays a central role in T-cell and natural killer cell responses, induces the production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ). |

| Fas-c and PPE-1 promoter |

1 |

Chimeric death receptor Fas and TNF receptor 1 and modified endothelium-specific pre-proendothelin-1 (PPE-1) promoter delivered by virus vector may trigger apoptosis of endothelial cells and reduce tumor angiogenesis. |

| HPV E6/HPV E7 |

1 |

Human papillomavirus oncoproteins. |

| TERT promoter |

1 |

Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter (TERT) is used to attenuate virus replication. |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-ɣ) |

1 |

IFN-ɣ is a cytokine molecule with pronounced cytostatic, pro-apoptotic and immune-stimulating effects. |

| Tyrosinase-related protein (TYRP1) |

1 |

TYRP1 is expressed in melanomas and on the surface of melanocytes and is an immunoreactive protein. |

| Anti-CTLA4 |

1 |

blocks CTLA-4 receptor and upregulate cytotoxic T –lymphocytes |

| None |

109 |

Many wild-type viruses have an oncolytic potential and are frequently used without payload. Attenuated or evolutionary selected viruses also demonstrate a strong antitumor effect. |

The thymidine kinase (TK) gene of the herpes simplex virus HSV-1 is often cloned into the genome of oncolytic viruses (24 studies). Such modification allows mediating the death of TK-expressing cells, ultimately increasing the therapeutic potential of OVs mediated by antiviral drugs (ganciclovir) [

47,

64,

229]. The gene encoding sodium iodide symporter (NIS) was used as a payload in the genome of VSV and measles virus (in 14 clinical studies) to visualize viral biodistribution and replication using CT and combination with radiotherapy. Other payloads include interferon-beta (INF-b) to improve oncoselectivity and stimulate the antitumor response, p53 to induce apoptosis, and MAGE-3 as one of the well-studied conservative tumor antigens—they were used in eight, six and three studies, respectively [

42,

171,

230]. However, it should be noted that in 109 out of 206 clinical trials (53%), oncolytics viruses without any transgenes were used.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/v13071271