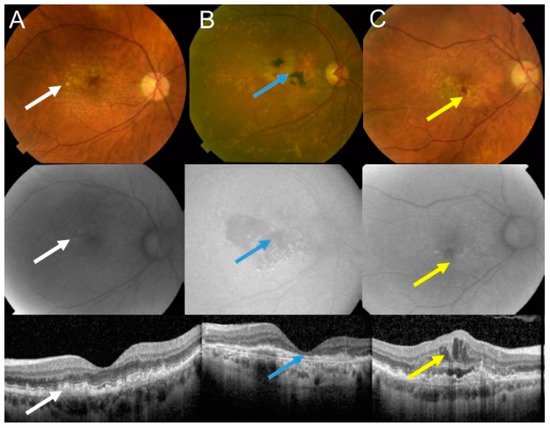

Figure 1. Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) may basically occur in two forms: dry and wet. Fundus photograph (upper panel), autofluorescence (middle panel), and optical coherence of intermediate dry AMD with drusen (white arrows) (A); advanced geographic atrophy (GA) with typical GA lesions (blue arrows) (B); and wet AMD with subretinal and intraretinal fluids and hemorrhage (yellow arrows) (C).

The pathogenesis of AMD is not completely known and many factors, both genetic/epigenetic and environmental/lifestyle-based, are involved. Oxidative stress is associated with AMD, but it is not exactly known what the source of such stress is and, in some cases, whether it belongs to the causes or consequences of the disease. Furthermore, oxidative stress can be linked with several putative or established AMD risk factors, including aging, smoking, blue light, obesity, and a diet rich in fat and carbohydrates [11,12,13]. The retina belongs to the most metabolically active tissues in humans with the highest oxygen consumption, resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as byproducts of retinal metabolism [14]. Likewise, aging, as per its definition as the main AMD risk factor, is associated with oxidative stress [15,16]. Also, mitochondria, the main source of energy and ROS production, may be central for AMD pathogenesis [17].

3. Telomeres and Telomerase in AMD

Telomeres are DNA–protein complexes at the ends of linear chromosomes in eukaryotes. They protect chromosomes against cellular exonucleases and prevent their recognition as a DNA double-strand break by DNA damage response (DDR) and chromosomal fusion. Telomerase is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase, which does not require an exogenous template to synthesize DNA.

Drigeard Desgarnier et al. analyzed the length of telomeres in different structures of the human eye [45]. They found that neural retina had the longest telomeres, whereas the cornea had the shortest. The length of telomeres in RPE cells was about four times shorter than in the neural retina. These authors did not observed either age-dependent telomere attrition in the retina or any difference in the telomere length between the macula and the rest of the retina.

High content of guanine in telomeric DNA may have at least two consequences. The first is the natural tendency of single-stranded, guanine-rich DNA to fold onto itself to form four-stranded structures due to the ability of guanine to form highly stable hydrogen bonds with other guanines—guanine quartets [47]. This property is important in the context of telomerase action, as four-stranded DNA is not a substrate for that enzyme. The second consequence follows from the fact that guanine has the highest number of oxidation-sensitive sites among all DNA bases [48]. Therefore, telomeres may be remarkably prone to oxidative stress, a common factor of AMD pathogenesis.

Recently, Banevicius et al. observed a higher relative telomere length in the peripheral leukocytes of patients with atrophic AMD than in healthy controls [

54].

There is no solid evidence unequivocally showing the activity of telomerase in the adult human normal retina, but several reports indicate that it can be activated in both normal and pathological conditions. In addition, many studies show exosomal expression and activation of telomerase in human retinal cells.

In their landmark work, Bodnar et al. showed that the RPE-340 human RPE cell line in an in vitro culture displayed telomere shortening and senescence, but their transfection with vectors encoding hTERT resulted in telomere elongation, reduced expression of β-galactosidase, a senescence and cellular aging marker, and extension of lifespan by at least 20 doublings [

55]. The authors observed a close correlation between extension of lifespan and telomerase activity, which, along with the normal karyotype displayed by transfected clones, indicated that stochastic mutagenesis did not account for observed changes. It is worth noting that virtually all control, i.e., hTERT, clones were senescent or nearly senescent, which raises questions about the suitability of human RPE cells cultures in the determination of physiological parameters and their limitations in studies on AMD pathogenesis.

In summary, studies on the association between telomere lengths in AMD performed in non-target tissue, mainly peripheral blood, did not bring consistent results, likely due to the heterogeneous population of AMD patients. Ectopic expression of telomerase in RPE cells improves telomeres, reduces senescence, and extends their lifespan. These effects, along with a report on the improvement of macular function due to an orally administered telomerase activator in early AMD patients, justify further studies on the potential of telomerase in AMD therapy.

4. Senescence, DNA Damage Response, and Autophagy May Underline the Involvement of Telomerase in AMD

Reactive oxygen species produced in oxidative stress may damage DNA and other biomolecules, including those important for DDR [62]. Therefore, impaired DDR may contribute to AMD pathogenesis. Furthermore, oxidative stress and ROS induce stress-induced senescence, different from replicative senescence, but with an even worse outcome [2]. As AMD belongs to the category of proteinopathies, disorders in which protein debris are formed, impaired autophagy is associated with AMD, but the mechanisms underlying this association are still incompletely known [63,64]. Telomerase is, per its definition, engaged in preventing replicative senescence and is reported to be involved in DDR and autophagy.

4.1. Senescence

There is a direct association between senescence and telomerase—telomerase prevents senescence in proliferating cells, extending their telomeres and protecting the cells against deletion in essential genes. Moreover, telomerase may extend telomeres that are shortened due to oxidative stress or any other stress resulting in telomere-associated DNA or protein damage.

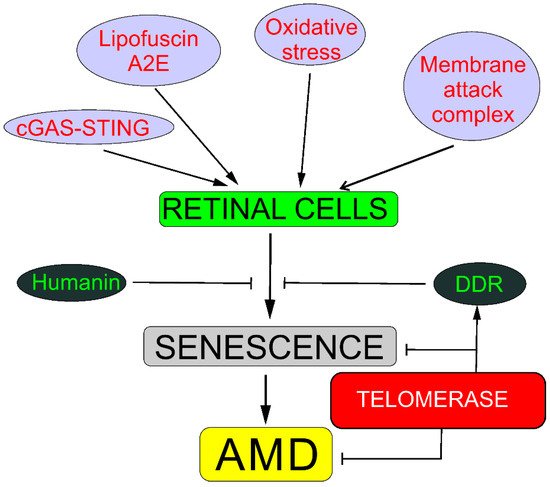

Senescence may be involved in AMD pathogenesis through several pathways, including oxidative stress response; DDR; humanin; degeneration of choriocapillaris mediated by membrane attack complex; the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS-STING) pathway; lipofuscin, including its fluorophore A2E (N-retinylidene-N-retinyl-ethanolamine), a byproduct of the visual cycle; and the amyloid-beta peptide (reviewed in [

2]). These pathways often overlap. Almost all, if not all, mechanisms of senescence induction in retinal cells are associated with DNA damage. Therefore, DDRs to such senescence-related DNA damage are crucial for senescence occurrence. Telomerase may ameliorate such damage and stimulate DDR, preventing not only replicative senescence but also senescence induced by oxidative stress and, in this way, senescence-related AMD (

Figure 2).

Figure 2. Telomerase may protect against senescence that may be causal in age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Oxidative stress evokes stress-induced premature senescence in all kinds of retinal cells, whereas membrane attack complex evokes degeneration of choriocapillaris through senescence in chorioretinal endothelial cells. Lipofuscin and its fluororophore A2E (N-retinylidene-N-retinyl-ethanolamine) show cytotoxic action against retinal cells through mechanisms with the involvement of redox reactions supported by the presence of iron in lipofuscin. Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase (cGAS) detects DNA in the cytosol, leading to the promotion of stimulator of interferon genes (STING), and induces senescence in the response to DNA damage. DNA damage response (DDR) may recover DNA damage, preventing oxidative shortening of telomeres or the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway. Humanin, a mitochondria-encoded peptide, exerts a protective effect against oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress in human retinal pigment epithelium cells and direct protection against senescence. Different background colors are for better distinguishing different elements.

4.2. DNA Damage Response

Oxidative stress is associated with overproduction of ROS, which may damage cellular macromolecules, including DNA. Oxidative stress damages telomeres, as their DNA is guanine-rich, and this is why they may be more susceptible to oxidative DNA damage than the “average” DNA in the rest of chromosomes.

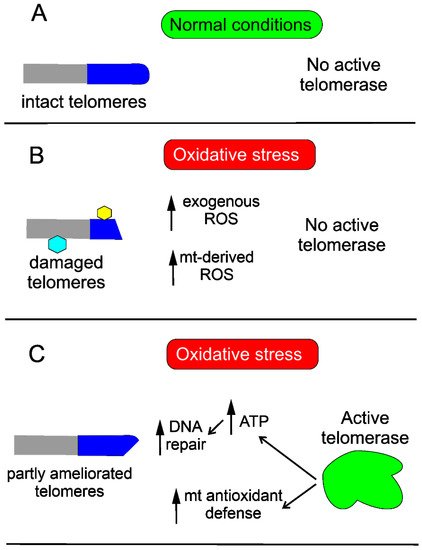

Telomerase may protect the cell against DNA damage through various mechanisms. Saretzki’s lab showed that overexpression of hTERT in human fibroblasts resulted in a decrease in mtDNA damage induced by oxidative stress [42]. To search for the mechanism underlying the observed changes, they showed that telomerase did not seem to increase the repair of mtDNA damaged by oxidative stress but induced an mitochondrial antioxidant defense mechanism [83]. Altogether, these results show that mitochondrial telomerase may protect nuclear DNA (nDNA) from oxidative stress-induced damage by decreasing mitochondrially produced ROS, which was directly shown for cancer cells [84]. However, it was demonstrated that ectopic expression of hTERT in human primary fibroblasts improved the kinetics of nDNA repair, likely due to an increase in the ATP level [85] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Telomerase improves telomeres damaged in oxidative stress. Telomeres (dark blue cap), intact in normal conditions (A), may be damaged in oxidative stress (B), which leads to stress-induced senescence. Damage to telomeres is presented as their shortening and modification (hexagons), also affecting the non-telomeric part of chromosomes (grey). Oxidative stress may be of endogenous and/or exogenous origin and is associated with reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation that may damage DNA and other macromolecules. Activation of endogenous telomerase or its ectopic expression ameliorates telomeres by improving mitochondrial (mt) antioxidant defense, resulting in decreased ROS levels as well as increasing ATP needed for DNA repair synthesis (C). Full recovery of telomeres also requires re-building of the telomere-related protein complex, not presented here.

4.3. Autophagy

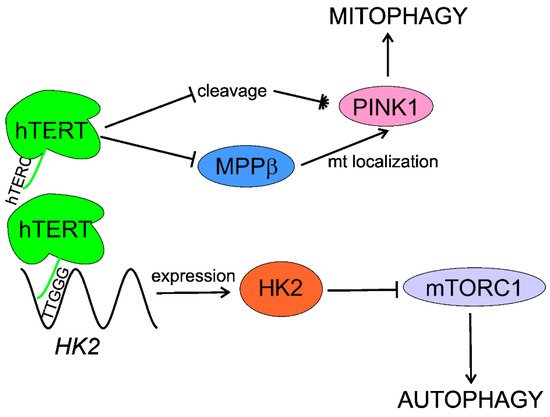

In summary, telomerase activates/stimulates autophagy through mTORC1 inhibition that may delay aging and age-related pathologies, including AMD. Telomerase may specifically activate mitophagy by regulation of the PINK1 protein. Although several independent studies show autophagy activation by telomerase, the exact mechanism of this activation is unknown and HK2 can lie between telomerase and autophagy (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Telomerase stimulates macroautophagy (autophagy) and mitophagy. The RNA component of human telomerase (hTERC) binds the 5′-TTGGG-3′ sequence within the promoter of the hexokinase 2 (HK2) gene, stimulating its expression. HK2 inhibits the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), which is a negative regulator of autophagy. The catalytic subunit of human telomerase (hTERT) negatively regulates cleavage of PINK1 (PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) induced kinase 1) and assists its mitochondrial (mt) localization through inhibition of mitochondrial processing peptidase β (MPPβ), stimulating mitophagy.

5. PGC-1α May Link Telomerase with AMD

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) is a member of the group of transcriptional activators of genes involved in energy metabolism (reviewed in [

51]). It is central for mitochondrial biogenesis, and this may imply its potential in aging and pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases [

52]. PGC-1α participates in muscle remodeling and regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [

107]. Except for pathological aging and neurodegenerative disorders, PGC-1α may be implicated in the pathogenesis of several other syndromes, including type 2 diabetes, cardiomyopathy, and obesity [

108,

109,

110].

It was shown that light stimulation of RPE cells enhanced the degradation of photoreceptor outer segments by these cells, which induced the activation of the PGC-1α/ERRα (estrogen receptor related alpha) pathway, which, in turn, upregulated VEGF. Therefore, targeting PGC-1α can be considered in anti-VEGF strategies to increase their efficacy in wet AMD treatment.

Mitochondria are the main source of energy production in cells. This process, even in normal conditions, is associated with the appearance of ROS that may damage biological macromolecules, including DNA. PGC-1α as a regulator of energy production can be also involved in the regulation of ROS production, especially as it is a crucial regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. It is generally accepted that PGC-1α is an important element of antioxidant defense [

111,

112,

113]. This role is attributed to the regulation of antioxidant enzymes by PGC-1α. However, other mechanisms of the involvement of PGC-1α in the antioxidant action can be considered [

114]. In general, the cellular antioxidant system contains three main classes of components: antioxidant enzymes, small molecular weight antioxidants, and DNA repair proteins. As PGC-1α is not an enzyme, it might play a role in DNA repair or more generally in DDR.

Mitochondrial damage in the RPE may be a trigger for events leading to degradation of RPE and photoreceptors, a hallmark of AMD [

120]. Therefore PGC-1α, as a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, is warranted to be studied in AMD pathogenesis (reviewed in [

121]). Moreover, PGC-1α also plays a role in the regulation of cellular oxidative stress response, important in AMD [

11,

24,

94,

122].

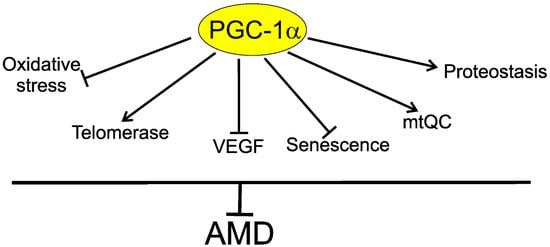

In summary, PGC-1α may be involved in AMD pathogenesis through several mechanisms, including decreasing oxidative stress in the retina; decreasing senescence of the retinal cells; regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key target in wet AMD therapy; and improving disturbed mitochondrial functions and autophagy. PGC-1α and TERT form an inhibitory positive feedback loop and loss of either protein results in loss of the other (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Telomerase is a component of the protective action of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α) against age-related macular degeneration (AMD). PGC-1α may directly or indirectly influence several proteins, mechanisms, and pathways important in AMD pathogenesis, including decreasing oxidative stress, senescence, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); ameliorating mitochondrial quality control (mtQC) and proteostasis, including autophagy; and stimulating telomerase, which can directly improve impaired telomeres in retinal cells or interact with proteins involved in their protection against factors of AMD pathogenesis.