The SOS family of Ras-GEFs encompasses two highly homologous and widely expressed members, SOS1 and SOS2. Despite their similar structures and expression patterns, early studies of constitutive KO mice showing that SOS1-KO mutants were embryonic lethal while SOS2-KO mice were viable led to initially viewing SOS1 as the main Ras-GEF linking external stimuli to downstream RAS signaling, while obviating the functional significance of SOS2. Subsequently, different genetic and/or pharmacological ablation tools defined more precisely the functional specificity/redundancy of the SOS1/2 GEFs.

- son of sevenless

- SOS1

- SOS2

- RAS signaling

- GEFs

S1. SOS2 vs. SOS1 Function: An Introductory Timeline Perspective

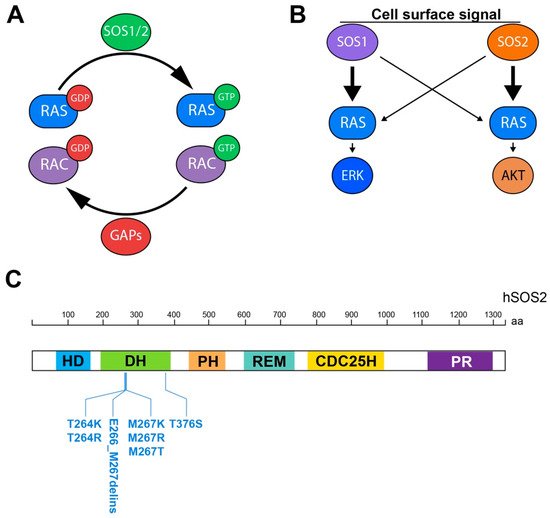

The proteins of the RAS superfamily are small GTPases known to shift between inactive (GDP-bound) and active (GTP-bound) conformations in a cycle regulated by activating Guanine nucleotide Exchange Factors (GEFs) that facilitate GDP/GTP exchange, and deactivating GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) that multiply their intrinsic GTPase activity (Figure 1A) [1,2,3,4].

Three main Ras-GEF families (RasGRF 1/2, SOS 1/2, and RasGRP l–4) have been described in mammalian cells with the ability to promote GDP/GTP exchange on the members of the RAS subfamily, and also some members of the RAC subfamily of small GTPases [5,6,7,8]. The members of the GRF family act preferentially, but not exclusively, in cells of the central nervous system [6,9,10], whereas the GRP family members function mostly in hematological cells and tissues [11,12]. In contrast, the members of the SOS (Son of sevenless) family are the most universal Ras-GEF activators, being recognized as the most widely expressed and functionally relevant GEFs with regards to RAS activation by various upstream signals in mammalian cells [5]. The SOS family encompasses two highly homologous, ubiquitously expressed members (SOS1 and SOS2) functioning in multiple signaling pathways involving RAS or RAC activation downstream of a wide variety of cell surface receptors [5,13].

The initial characterization of the first available constitutive knockout (KO) mouse strains of the SOS family showed that SOS1 ablation causes mid-embryonic lethality in mice [14,15], whereas constitutive SOS2-KO mice are perfectly viable and fertile [16]. Because of this and the stronger phenotypic traits associated to SOS1 ablation, most early functional studies of the SOS family focused almost exclusively on SOS1, and rather little attention was paid to analyzing the functional relevance of SOS2 [5]. The view that SOS1, but not SOS2, is the key GEF family member in RAS-signal transduction in metazoan cells was also probably behind the long search for, and development of, specific, small-molecule SOS1 inhibitors that have recently reached preclinical and clinical testing against RAS-driven tumors [5,17,18].

Despite the earlier lack of focus on the functional relevance of SOS2, many subsequent studies have uncovered specific functions unambiguously attributed to SOS2 in different physiological and pathological contexts that clearly document the functional specificity of this particular SOS GEF family member.

In particular, the development, about 8 years ago, of conditional, tamoxifen-inducible, SOS1-null mutant mice made it possible to bypass the embryonal lethality of SOS1-null mutants and opened the way to carry out relevant functional studies of SOS2 by allowing biological samples originated from adult mouse littermates of four relevant SOS genotypes (WT, SOS1-KO, SOS2-KO and SOS1/2-DKO) to be generated and functionally compared [19]. Somewhat surprisingly, adult SOS1-KO or SOS2-KO mice were perfectly viable, but double SOS1/2-DKO animals died very rapidly [19], demonstrating a critical contribution of the SOS2 isoform (at least when SOS1 is absent) at the level of full organismal survival and homeostasis, and thus opening new avenues for consideration of SOS2 as a functionally relevant player in mammalian RAS signaling pathways. In this regard, a number of recent functional studies of SOS1 and SOS2 using diverse genetic and pharmacological SOS ablation approaches have significantly clarified, during the last decade, the mechanistic details underlying the functional specificity/redundancy of the SOS1 and SOS2 GEFs in a wide array of tissues and cells, both under physiological and pathological conditions [20,21,22,23,24,25] (see [5] for a review).

Specifically, detailed functional comparisons between primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) extracted from SOS1-KO and/or SOS2-KO mice have documented a dominant role of SOS1 over SOS2 regarding the control of a series of critical cellular physiological processes, including cellular proliferation and migration [20,21], inflammation [22], and maintenance of intracellular redox homeostasis [20,26]. The functional prevalence of SOS1 is not limited to the above-mentioned physiological contexts, but has also been demonstrated under different specific pathological contexts. In particular, a specific, critical requirement of SOS1 was demonstrated for development of BCR–ABL-driven leukemia [24,27], as well as in skin homeostasis and chemically induced carcinogenesis [21,28]. Likewise, both SH2P and SOS1 have been shown to be essential signaling mediators in wild-type KRAS-amplified gastroesophageal cancer [5,29].

As described above, most reports support the functional dominance of SOS1 over SOS2 regarding their participation in control of several major intracellular processes, such as proliferation, migration, inflammation, or regulation of intracellular ROS levels [20,25]. Remarkably, in all those processes, the defective cellular phenotypes observed in SOS1/2-DKO samples are always much stronger than in single SOS1-KO cells, while undetectable in single SOS2-KO contexts, suggesting a specific, ancillary role of SOS2 that only becomes easily visible in the absence of SOS1 [19,20,21,30].

Regarding the participation of SOS1 and SOS2 in Ras signaling pathways, the initial analyses of constitutive SOS1-KO mouse embryo fibroblast (MEF) cell lines indicated that SOS1 (but not SOS2) is required for long-term activation of the Ras-ERK pathway, with SOS1 participating in both short-term and long-term signaling, while SOS2-dependent signals are predominantly short-term [14]. More recent studies analyzing inducible SOS1-KO biological samples in mouse keratinocytes also support that view [25] and have also confirmed that SOS1 is the dominant player regarding the process and kinetics of RAS activation (GTP loading) upon cell stimulation by various upstream signals and growth factors [20,25]. Of relevance also are other recent studies in cell lines devoid of SOS1 and/or SOS2 that have described the specific, primary involvement of SOS2 in regulation of the PI3K/AKT signaling axis, whereas SOS1 appears to be the dominant player in the MEK/ERK signaling axis [25,30,31,32]. Furthermore, regarding SOS2 functional specificities in cellular pathological contexts, a hierarchical requirement for SOS2 to mediate RAS-driven cell transformation has also been reported recently in certain cell populations [31,32].

EGF-dependent RAS– RAF signaling has been shown to be essential for epidermal development and carcinogenesis [33,34,35]. In this regard, it was also shown that SOS1 upregulation resulted in development of skin papillomas with 100% penetrance, supporting a critical role of SOS in this process in epidermal cells [28].

More recently, our laboratory has also characterized/analyzed in detail the specific involvement of SOS1 and/or SOS2 in homeostasis of the skin, as well as in tumoral and nontumoral skin pathologies [21,25]. Our initial studies in adult KO animal models showed that SOS1 ablation (but not SOS2 ablation) produced significant alterations of the overall layered structure of the skin in adult mice, although, interestingly, these skin architectural defects were markedly worsened when both SOS1 and SOS2 proteins were concomitantly ablated [21]. Furthermore, the skin of adult SOS1-ablated mice and, more markedly, SOS1/2-DKO mice showed a severe impairment of its physiological ability to repair skin wounds, as well as almost complete disappearance of the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response in the injury site. In addition, SOS1 disruption (but not SOS2 ablation) delayed the onset of tumor initiation, decreased tumor growth, and prevented malignant progression of papillomas when using the known DMBA/TPA model of chemically induced skin carcinogenesis in mice [21].

While these observations demonstrated that SOS1 is clearly predominant with regards to skin homeostasis, wound healing, and chemically induced skin carcinogenesis, it still remained unclear whether the defective phenotypes observed in the skin of SOS1-deficient mice were cell-autonomous or depended on their local manifestation in specific cell compartments of the skin. We have addressed these questions in a recent report involving extensive detailed analyses of the specific subpopulation of keratinocytes present in the skin of both newborn and adult SOS1-KO While these studies confirmed the prevalent role of SOS1 over SOS2 in regulation of the proliferation of primary mouse keratinocytes, our detailed analyses of primary keratinocytes derived from newborn and adult mice of four relevant SOS genotypes (WT, SOS1-KO, SOS-KO, and SOS1/2-DKO) uncovered previously unrecognized functional contributions of SOS2 regarding skin architecture, as well as proliferation, differentiation, and survival of primary keratinocytes [25]. As this population is essential for replacing, restoring, and regenerating the mouse epidermis, these data confirm that SOS2 plays specific, cell-autonomous functions (distinct from those of SOS1) in keratinocytes, and reveal a novel, essential role of SOS2 in control of epidermal stem cell homeostasis [21,25].

Growing experimental evidence has accumulated in recent years that supports the functional implication of SOS GEFs in human tumors and other RAS-related pathologies. In this regard, a significant number of gain-of-function SOS1 mutations (and, more rarely, SOS2 mutations), resulting in subsequent hyperactivation of RAS signaling, have been identified in inherited RASopathies, such as Noonan syndrome (NS) or hereditary gingival fibromatosis, as well as in various sporadic human cancers, including endometrial tumors and lung adenocarcinoma, among others [5]. However, during the last few years, a previously undetected but relevant involvement of SOS2 in some of these pathologies is also coming to light in a series of studies describing specific SOS2 gene alterations that have been identified in several forms of cancers and RASopathies, as well as the potential therapeutic effect of explicit SOS2 removal in certain tumor cell lines [36,37,38,39,40]. All in all, these observations and the above-described timeline of experimental evidence support the notion that, besides SOS1, SOS2 may also constitute a worthy therapy target for prevention and/or treatment of some specific tumor and nontumor pathologies with epidermal origin or dysregulated PI3K/AKT signal transmission [25].

RAS oncoproteins were sometimes considered “undruggable” in the past, but that notion has been proven wrong by the development of promising inhibitors that are currently being characterized at different stages of preclinical and clinical testing [5,41]. In addition, a renewed interest has recently emerged to target SOS proteins in an effort to attenuate oncogenic signaling in tumors harboring altered RTK–RAS–ERK signaling pathways (Table 1). In this regard, new small-molecule SOS1 inhibitors have been obtained in the last few years with the ability to either (i) interfere with the functional SOS:RAS interactions, or (ii) to limit the intrinsic GEF activity of SOS1 protein [5] (Table 1).

| Compound | Mode of Action | Preclinical/Clinical Trial Identifier | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sotorasib (AMG510) | KRASG12C inhibitor | NCT04185883 NCT03600883 NCT04303780 |

[43,44,45] |

| BAY-293 | SOS1 inhibitor | Preclinical | [30,47] |

| BI-3406 | SOS1 inhibitor | Preclinical | [23] |

| BI-1701963 | SOS1 inhibitor | NCT04111458 | https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04111458 (accessed on 20 June 2021) |

Regarding the first group, one of the most promising direct RAS inhibitors developed so far is the KRASG12Cinhibitor AMG510, recently named Sotorasib in clinical settings [42]. In particular, a phase 1 trial (NCT04185883;https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04185883(accessed on 20 June 2021)) described Sotorasib anticancer activity in patients with KRASG12C-mutated advanced solid tumors, with a particularly potent beneficial effect in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [43]. In addition, a phase 2 clinical trial (NCT03600883;https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03600883(accessed on 20 June 2021);Table 1), showed that Sotorasib therapy resulted in a long-term clinical benefit in patients with previously treated KRASG12C-mutated NSCLC [44]. Finally, a randomized phase III trial (NCT04303780;https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04303780(accessed on 20 June 2021)) currently recruiting patients is devoted to comparing Sotorasib with docetaxel in advanced NSCLC patients with KRASG12Cmutation who have progressed after combination of platinum-based chemotherapy and checkpoint inhibitor [45].

Regarding the group of small-molecule, direct SOS inhibitors, only drugs designed to act against SOS1 are available at this moment, whereas inhibitors specifically acting on SOS2 are not yet described [5,46] On the other hand, BI-3406, the first-in-class, orally bioavailable, in vivo tested, direct SOS1-inhibitor elicits activity against many KRAS variants, including all major G12 and G13 oncoproteins, and demonstrates synergistic therapeutical effects if combined with MEK inhibitor [23]. Moreover, a combination of BI-3406 and trametinib has potent activity against secondarily acquired resistance due to new KRAS mutations [48]. Finally, a phase I clinical trial (NCT04111458;https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04111458(accessed on 20 June 2021);Table 1) has also recently been started with BI-1701963 (a compound which exhibits high similarities in its mode of action with BI-3406) [46] that is focused on patients with advanced KRAS-mutated cancers, in order to evaluate safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamic properties (Table 1).

Inhibitors of SOS GEF function in pathological contexts. List of compounds and experimental evidence documenting their ability to disrupt functional interactions of SOS and RAS targets in RAS:SOS complexes, or to directly inhibit the intrinsic GEF activity of SOS proteins.

The following sections in this review focus on different aspects of SOS2 function in various physiological processes and pathological contexts, and also pinpoint some remaining questions still requiring further clarification about potential, specific functional role(s) of SOS2. It is apparent that further, comprehensive functional analysis of specific tissue/cell lineages will be needed to fully unveil the specific functional contributions of SOS2 in various health and disease contexts. Although SOS2 was frequently considered in the past as the “ugly duckling” of the SOS family, the more recent and complete studies of the regulatory and functional aspects of the SOS family members support the notion that SOS2 may well become a “swan”.

2. SOS2 and SOS1: So Similar but So Functionally Different. Some Mechanistic Considerations

As mentioned above, despite their remarkable homology, it is apparent that SOS1 is critically required for more functionally relevant roles than SOS2, but very little is known about the precise mechanistic reasons explaining the noticeable functional differences observed between both SOS isoforms in different physiological cellular contexts.

An initial, simplistic consideration in the search for mechanistic explanations might dwell on the analysis of potential differences of expression levels between SOS1 and SOS2 in different biological contexts. For example, the initial detection of high expression levels of SOS1 mRNA and protein in placental labyrinth trophoblasts, whereas SOS2 levels were significantly lower [14], offered a likely explanation for the observation that SOS2 presence is not sufficient to rescue the mid-gestation lethality caused by the absence of SOS1 in constitutive SOS1-KO mice [14]. In contrast, the fact that SOS1 and SOS2 are almost ubiquitously expressed at significant intracellular concentrations in most postembryonal organs/tissues/cells examined [5] indicates that mechanisms other than expression level may account for the dominant role of SOS1 regarding cellular proliferation, migration, inflammation, or control of intracellular redox homeostasis Interestingly, despite the seemingly prevalent functional contributions of SOS1 in comparison to SOS2, analysis of large database sets of available microarray hybridization expression data shows the presence of higher amounts of SOS2 transcripts than of SOS1 transcripts in different cellular settings [21,25].

Curiously, most SOS-related transcriptional data accessible in public databases deal with SOS1-dependent transcriptomic alterations networks observed in various native or drug-treated tumors and pathologies [5,23,50,51], and much less information is available regarding the characterization of the specific transcriptional networks driven by the presence of SOS1 or SOS2 in different cellular physiological contexts In this regard, our comparison of transcriptional networks of primary cells derived from SOS1-KO and/or SOS2-KO mice has revealed a remarkably higher impact of SOS1 ablation than SOS2 ablation on the resulting transcriptomic profiles. Interestingly, we observed that SOS2 depletion resulted in practically negligible alterations as compared to SOS1 ablation in primary MEFs (unpublished) and keratinocytes [25]. Furthermore, as with other phenotypic alterations [19,20,21,22,23,25], concomitant ablation of SOS1 and SOS2 caused significantly higher alterations of the transcriptional patterns than single SOS1 depletion, suggesting a possible adjuvant role of SOS2 in this regard when SOS1 is already absent.

A number of biochemical differences between SOS1 and SOS2 GEF proteins that have been reported in the literature [5] are also likely to be highly significant factors contributing to the different functionalities exhibited by these two isoforms in different biological contexts. Among other functional aspects, these different biochemical properties are thought to impact on the protein half-life and the intracellular stability and homeostasis of the SOS1 and SOS2 GEF proteins, as well as on the various protein–protein interactions (PPI) in which they can engage under different biological conditions. [52], or that SOS1 proteins are more stable than SOS2 proteins since the latter seem to be degraded by a ubiquitin- and 26S proteasome-dependent process in mouse cells [53,54]. Furthermore, a recent report has also described specific in vivo direct interactions of SOS1 with the CSN3 subunit of the COP signalosome and PKD, which may contribute to homeostatic control of intracellular RAS activation [55].

Differences in 3D structure and regulation may also contribute to the differential functionality of SOS1 and SOS2. The allosteric binding of RAS•GTP to the SOS1 REM domain was clearly shown to relieve SOS1 autoinhibition and create a positive feedback loop of RAS activation, thus altogether increasing the catalytic activity of SOS1 [5,56]. However, the scope and significance of the potential allosteric activation of SOS2 via its own REM domain remains undefined at this time [57]. More extensive analyses of full-length SOS2 protein crystals are bound to provide additional valuable information in this regard in the future.

Many prior reports have documented the ability of the SOS GEFs to act as bifunctional GEF activators capable of activating not only all members of the RAS protein family, but also some members of the RAC family of proteins. In view of this, some functional disparities displayed by SOS1 and SOS2 in different cellular contexts might also be linked, at least in part, to their specific, potentially differential participation in processes of activation of RAS and/or RAC intracellular proteins upon cellular stimulation by different external signals [5,13,20,24].

Mechanistically, the SOS GEFs are known to promote signal internalization and subsequent RAS/RAC activation through a process involving their recruitment from the cytosol to the plasma membrane via complex formation with different adaptor proteins (refs). Although the precise mechanistic details remain yet poorly understood, it is generally accepted that SOS-mediated activation of RAC requires recruitment of SOS–E3B1 complexes to actin filaments found within membrane ruffles, thus facilitating RAC activation by the DH (Dbl homology) domain. In any case, the high homology shared by SOS1 and SOS2 in their overall modular protein structure/sequence and, in particular, in their DH domains responsible for RAC activation (overall 84% similarity and 70.6% amino acid identity) [5], together with the experimental demonstration of physical interaction between hSOS2 and hE3B1 in COS cells [59], support the notion of postulating SOS2 as a potential RAC activator, at least in certain cellular contexts. Interestingly, direct analysis of primary SOS1/2 KO primary MEFs has shown that single ablation of either SOS1 or SOS2 did not impair the overall level of EGF-dependent RAC activation, whereas combined SOS1/2 depletion significantly reduced the levels of RAC activation [20], suggesting functionally redundant contributions of SOS1 and SOS2 with regards to RAC activation after EGF stimulation [20].

After surface receptor stimulation and subsequent SOS-mediated RAS activation, the GTP-loaded RAS proteins are known to activate various downstream signaling pathways which are essential for the control of a wide variety of cellular processes. 3-kinase (PI3K) has also been shown to have an essential role in processes such as cell survival, cytoskeleton reorganization, cell motility or invasiveness, among others [60]. Since a well-regulated balance between the RAS–ERK and RAS–PI3K signaling axes is essential for adequate cellular signaling homeostasis, it will be relevant in this regard to elucidate the relative functional contributions of SOS1 and SOS2 to either signaling axis in different cellular contexts [5]. These recent observations in keratinocytes confirm and extend previous reports in primary MEFs and in a wide array of tumor cell lines that also demonstrated a preferential role of SOS1 in the control of cell proliferation and activation of the RAS–ERK pathway [5,20,21].

The notion of specific, relevant functional cellular roles played by SOS2 is firmly supported by studies from R. Kortum´s lab demonstrating that SOS2 promotes EGF-stimulated AKT phosphorylation in cells expressing mutant RAS. In particular, single SOS2 ablation or silencing in a variety of mouse and human cell lines results in significant reduction of AKT, but not ERK, phosphorylation and ability for anchorage-independent growth in RAS-mutant cells The same lab has also reported the potential involvement of SOS2 in SHP2-mediated signaling pathways [30]. Overall, the observation that SOS2-dependent PI3K/AKT signaling appears to be crucial for transformation in cells harboring mutant KRAS genes [31,32] suggests that SOS2 could be considered as a potential therapy target in KRAS-driven oncogenic processes with dysregulated PI3K/AKT signal transmission

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22126613