Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Microbiology

Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph: Gibberella zeae) is a pathogen of maize, wheat, rice, and barley responsible for the disease known as Fusarium head blight (FHB) and mycotoxin contamination. Several studies have explored in depth the biochemistry and genetics of the pigments present in Fusarium graminearum. Still, there is a need to discuss their relationship with the mold’s observable surface color pattern variation throughout its lifecycle.

- Fusarium graminearum

- color

- pigments

- polyketides

- carotenoids

1. Introduction

Fusarium graminearum (teleomorph: Gibberella zeae) is a pathogen of maize, wheat, rice, and barley responsible for the disease known as Fusarium head blight (FHB) and mycotoxin contamination [1,2]. FHB destroyed the grain starch and protein and was responsible for losses of over $2.7 billion in the United States between 1998 and 2000 [2]. The mold’s most common mycotoxins are nivalenol (NIV) and deoxynivalenol (DON) [3], usually occurring together and frequently associated with gastrointestinal disorders, among other health impairments [4]. However, there are other relevant toxins, such as zearalenone (ZEA) [5], an estrogenic compound capable of causing abortion and other reproductive complications [6,7].

Very few studies comprehensively describe and relate F. graminearum surface colors and its pigments, their properties, and biosynthetic or genetic origin, though some were isolated during the 1930s–1960s [8,9,10,11,12]. There was also considerable chemical analysis of Fusarium pigmentation in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but this never tried to relate the compounds with the mold’s observable biological phenomena [13]. Recent sequencing of the F. graminearum genome and development of gene replacement tools allowed major progress in genetic and biochemical studies [13]. Now, it is known that the red pigmentation of F. graminearum is due to the deposition of aurofusarin in the walls [2,14], but it is likely to be the combination of several pigments [15,16].

Pigmentation is part of the mold growth process, and it can be used as a tool for growth studies as an alternative to the expansion in size [17]. This approach can help overcome spatial constraints in fungal studies or applications, such as the limited size or particular shape of a Petri dish or bioreactor, or even predict toxin production solely by analyzing the mold surface color. For instance, mutants with the absence of the pigment aurofusarin seem to produce an increased amount of ZEA [2], and histone H3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me) is important for the transcription of genes for the biosynthesis of both DON and aurofusarin [18]. Thus, there is some connection between the production of major Fusarium mycotoxins and pigments.

2. F. graminearum Colors throughout Its Lifecycle

It is first important to know that there is no single set of colors to describe F. graminearum throughout its lifecycle. The surface colors change depending on several variables, such as strain, maturity, nutrients, temperature, pH, water activity, light exposure, and aeration [8,10,16,17]. Ashley et al. [8] mentioned early studies identifying pH as the main determinant of Fusarium colors, “so that the same culture may be orange or yellow-colored at an acid reaction, the color changing to red or blue when the medium becomes alkaline.” Medentsev et al. [19] said that the biosynthesis of naphthoquinones (major secondary metabolites, including pigments) is the mold’s main response to stress. F. graminearum has different types of pigments, all with distinct properties [8,15,20,21,22], from which we have to expect numerous combinations and the resulting chromatic attributes. For instance, the teleomorph was found to have violet pigmentation in its perithecia [23]. Thus, it is impractical to summarize all possibilities. For this reason, this description will focus on the mold grown on yeast extract agar (YEA) at 25 °C as an example (Figure 1). The isolate was obtained from the Catalogue of the Japan Collection of Microorganisms (JCM), where it is registered as the teleomorph Giberella zeae (Schwabe) Petch, and it was isolated by Sugiura [24] from rice stubble in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan.

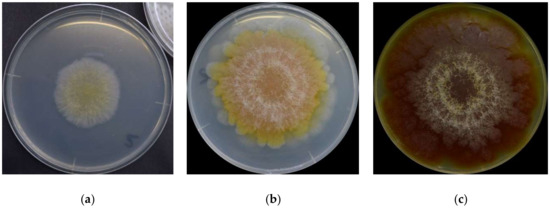

Figure 1. F. graminearum surface colors on its (a) 3rd day, (b) 6th day, and (c) 16th day.

YEA is a highly nutritive medium containing agar as a solidifier, peptic digest of animal tissue, and yeast extract, and is thus rich in nitrogenous compounds, vitamin B, and other nutrients [25]. Furthermore, yeast extracts do not seem to affect the quality or level of aurofusarin, a major pigment, by any Fusarium species [26]. This is important because it is desirable to use the mold’s original coloration in the studies without changing it much because of the nutrients available.

F. graminearum colors change in a very consistent and predictable pattern [17]. At a glance, the mold germinates as a pale mycelium and starts to acquire a yellowish coloration between its third and fourth day. It attains its full orange tone on the sixth day and then shifts to dark wine red by the 16th day. The color distribution is heterogeneous: it forms a radial gradient, with the center more intensely colored and increasingly pale surroundings. Kim et al. [1] described the F. graminearum as a “yellow to tan mycelia with the white to carmine-red margins,” certainly depending on the condition in which it grows. A dominant red color tends to become more evenly distributed as the fungus ages, and alternated concentric layers of white and red rings close to the center become increasingly evident. The white rings are hairy and seem to be formed of colorless hyphae. The medium’s color change (Figure 1c) from pale to yellow is due to the accumulation of aurofusarin [14].

A recent analysis based on red, green, and blue (RGB) channels taken for F. graminearum photographs shows that the three color components are positively correlated and all exhibit a third-degree polynomial trend when measured throughout the first 20 days of its lifecycle, and it makes the colors a potential tool to replace size-based measurements for growth studies and to predict toxin production [17].

3. Major F. graminearum Pigments

Most of what is known about the pigmentation of F. graminearum comes from studies on F. culmorum, F. aquaeductuum, F. fujikuroi, and F. oxysporum, and eventual confirmation that the pigments occur across species [15]. Such studies aim to enhance pigment production for the dye industry as an alternative to synthetic counterparts [27]. A pioneering study by Ashley et al. [8] identified aurofusarin, rubrofusarin, culmorin, and their derivatives among the pigments. Since then, others have been mentioned, including perithecial melanin [28] and carotenoids [15]. The most relevant carotenoids from F. graminearum are perhaps neurosporaxanthin and torulene [14,15,21].

F. graminearum pigmentation is very complex, but most pigments have similar colors, ranging from yellow and orange to red. Thus, it is not easy to know how much each pigment contributes to its color. Nevertheless, the literature points towards aurofusarin and neurosporaxanthin, and possibly also rubrofusarin, as the ones impacting F. graminearum’s surface color the most. No source has simultaneously covered non-carotenoid and carotenoid pigments, and the ones describing each of these classes showed the tendency to state the respective compounds as the main source of coloration, maybe because the pigments have similar colors. It would be a good idea to find out which contributes the most to the coloration, perhaps by experimentation based on the distinctive properties of the pigments. For instance, carotenoids are expected to be reactive to light, but as far as the literature has shown, polyketides such as aurofusarin and rubrofusarin are not likely to change considerably in the presence and absence of illumination. By simple observation, aurofusarin appears predominant because F. graminearum specimens grown in dark and illuminated settings do not seem to present different coloration when maintained at the same temperature.

In any case, the color change has previously been demonstrated to follow a predictable trend, disregarding the pigments involved. Thus, whichever the dominant pigments follow a consistent pattern over time. It is still difficult to advocate if the changes are mostly due to variations in the proportion of different pigments or chemical reactions leading to changes of the same compound into its derivatives, just like the case of aurofusarin at different pH settings. It could even be simply the breakdown of aurofusarin into rubrofusarin molecules.

There are two more aspects to consider before listing F. graminearum pigments or related compounds. Culmorin is colorless, but it is included in this review because it was isolated together for the first time during studies of Fusarium pigmentation. Bikaverin and fusorubin are Fusarium pigments [19,29,30], but they are not included in the following list because there is very little evidence about their occurrence and impact on the coloration of F. graminearum.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods7100165

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!