A solid tumor mass consists not only of cancer cells, but of numerous other resident and infiltrating cells and the extracellular matrix, which together form the tumor microenvironment (TME). The TME contains three main cell entities: fibroblasts, immune cells and endothelial cells. Endothelial cells control their microenvironment through the expression of membrane-bound and secreted factors. Such angiocrine functions are frequently hijacked by cancer cells, which deregulate the signaling pathways controlling the expression of angiocrine factors.

- angiocrine

- blood vessels

- endothelial cells

- cancer

- tumor progression

1. Tumor Angiogenesis

The limited diffusion distance of oxygen requires that almost every cell of the body is within 100 to 150 µm of a capillary [1]. Therefore, the growth of a solid tumor usually requires the growth of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones [2]. This is achieved by the re-activation of the quiescent resident vasculature by growth factors such as the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secreted from cells within a hypoxic tissue. In a physiological setting, the growth of new blood vessels would lead to oxygen and nutrient delivery resulting in a reduced secretion of pro-angiogenic factors and the adoption of a quiescent vascular phenotype. In tumors, however, there is often persistent vascular growth factor secretion (e.g., due to mutations in cancer cells or by certain immune cells), and this results in aberrant angiogenesis, leading to a chaotically structured vasculature with impaired perfusion, cellular junctions integrity and poor coverage with mural cells (pericytes and vascular smooth muscle cells). This poorly functional vasculature further promotes hypoxia, immunosuppression and thereby tumor progression [3]. Here, we do not intend to further discuss tumor angiogenesis, as this has been extensively done by others [4][5][6]. However, it is important to mention that the immature tumor vasculature, lacking proper coverage with mural cells, provides a large signaling platform which, besides the release of soluble angiocrine factors, also enables ligand-receptor interactions of membrane-bound proteins between ECs and cancer cells or other cells of the TME.

We would like to mention only briefly that, based on the concept of tumor angiogenesis [7], anti-angiogenic cancer therapy has been developed and is nowadays the standard care in several tumor entities [8]. Despite the promising and impressive efficacy in prolonging progression-free survival, there is limited impact on overall survival. This might be due to acquired resistance mechanisms, such as the recruitment of alternative angiogenic pathways [9][10]. Very recently, fascinating data were reported showing that the combination of immunotherapy with anti-angiogenic treatment improves the outcome in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma [3][11]. The phase 3 IMBrave trial investigated a treatment with antibodies against VEGF (Bevacizumab) and PD-L1 (Atezolizumab) against the standard treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor Sorafenib. The overall survival at 12 months was 67.2% (95% CI, 61.3 to 73.1) with Atezolizumab-Bevacizumab and 54.6% (95% CI, 45.2 to 64.0) with Sorafenib [11]. This promising finding demonstrates that there are important functions of ECs that go beyond the formation of new blood vessels. In the following chapters we will discuss these with a focus on angiocrine functions.

2. Beyond Angiogenesis

Under physiological conditions, ECs coordinate organ development, regeneration and homeostasis by angiocrine factors in an organ-specific manner [12][13][1]. There is increasing evidence that cancer cells can take advantage of such functions to generate a microenvironment that promotes tumor progression. We will first summarize the angiocrine factors which play a pivotal role in tumor models and subsequently discuss their roles in several aspects of tumor progression, immunosuppression and metastasis.

2.1. Angiocrine Factors

A number of soluble and membrane-bound angiocrine factors that influence tumor progression through action on the cancer cells themselves or on the local immune cells in the TME were discovered in the last years (Table 1). Several of these can be grouped into: (i) EC adhesion proteins, like intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), E-selectin and P-selectin, which are involved in the recruitment of leukocytes but also in the transmigration of cancer cells across the vessel wall; and (ii) chemokines, like interleukin-8 (IL-8 also known as CXCL8), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1; also known as CCL2), stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF1; also known as CXCL12) and other factors which influence the recruitment and polarization of immune cells [12][14].

Table 1. List of tumor-induced angiocrine factors and their described functions.

| Angiocrine Factor 1 | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ang-2 | Invasion/metastasis; myeloid cell recruitment | [15][16][17][18] |

| Biglycan | TCs invasion/metastasis | [19] |

| CCL2/MCP-1 | Myeloid cells recruitment; tumor cell extravasation | [20] |

| CCL5 | EMT; invasion | [21][22] |

| CXCL1 | Invasion | [23][24] |

| CXCL8/IL8 | Stemness; invasion; myeloid cell recruitment; lymphocyte phenotype | [20][23][25] |

| CXCL12/SDF-1 | Stemness | [26] |

| DLL4 | Cancer cell proliferation; invasion | [27][28] |

| EGF | EMT | [29] |

| Endothelin | Cancer cell proliferation | [30][31] |

| EphrinA1 | Transendothelial migration | [32] |

| FGF | Stemness | [33] |

| ICAM1 | Myeloid cell recruitment/adhesion; lymphocyte phenotype | [34][35][36] |

| IGF1 | Stemness | [37] |

| IL6 | Myeloid cell recruitment/activation; stemness; lymphocyte phenotype | [38][39] |

| Inf- γ | Lymphocyte phenotype; T cell inhibition | [40] |

| Laminin | ECM; invasion/metastasis | [41][42] |

| MMPs | ECM | [43] |

| Notch signaling/Jag1 | Stemness; CSCs; immune cell recruitment; metastasis | [44][45][46][47] |

| PD-L1 | T cell inhibition | [48][49][50] |

| Selectin | Myeloid cell recruitment; immune cell and tumor cell transmigration/extravasation | [51][52][53][54][55][56][57] |

| Shh | Stemness | [58] |

| Slit2 | Cancer cell proliferation, intravasation, metastasis | [59][60] |

| Tim-3 | T cell inhibition | [61][62] |

| TSP-1 | Pre-metastatic niche | [63] |

| VEGF family | Angiogenesis; cancer cell proliferation; stemness; myeloid cell recruitment; lymphocyte phenotype | [64][65][66] |

| VCAM1 | Myeloid cell recruitment/adhesion; metastasis | [18][47][67] |

1 Ang2: Angiopoietin-2, CCL2: C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2, CCL5: CC-chemokine ligand 5, CXCL1: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1, CXCL8: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8, CXCL12: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12, DLL4: Delta-like 4, EGF: Epidermal Growth Factor, FGF: Fibroblast Growth Factor, ICAM1: Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, IGF1: Insulin-like growth factor 1, IL6: Interleukin-6, Inf-γ: Interferon-γ, MMPs: Matrix metalloproteinases, ECM: Extracellular matrix, PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1, Shh: Sonic Hedgehog, Tim-3: T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3), TSP-1: Thrombospondine-1, VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor, VCAM1: Vascular cell adhesion protein 1.

2.2. Angiocrine Control of Cancer Progression

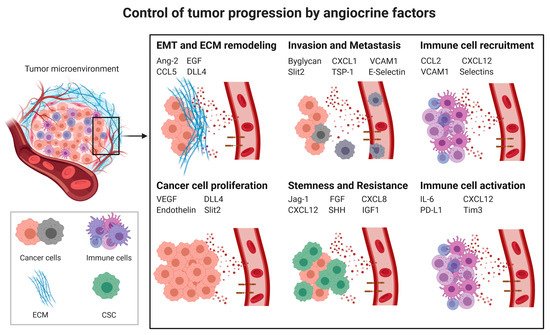

Cancer progression is a complex process involving cancer cell proliferation, acquisition of different cancer cell phenotypes, such as stemness or epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM), tissue invasion, intravasation, extravasation, immunosuppression (Section 2.3) and formation of metastases. All of these processes are influenced by angiocrine factors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Control of tumor progression by angiocrine factors; CSC: cancer stem cells; EMT: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition; ECM: Extracellular matrix; Ang2: Angiopoietin-2, CCL2: C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2, CCL5: CC-chemokine ligand 5, CXCL1: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1, CXCL8: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8, CXCL12: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12, DLL4: Delta-like 4, EGF: Epidermal Growth Factor, FGF: Fibroblast Growth Factor, ICAM1: Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, IGF1: Insulin-like growth factor 1, IL6: Interleukin-6, PD-L1: Programmed death-ligand 1, Shh: Sonic Hedgehog, Tim-3: T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3, TSP-1: Thrombospondine-1, VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor, VCAM1: Vascular cell adhesion protein 1.

2.2.1. Cancer Cell Proliferation

Blood vessel formation is essential for tumor growth, as it depends on a proper nutrient and oxygen supply. VEGF is not only a master regulator of angiogenesis [2] and the immune response [68] but can also stimulate tumor cell proliferation in breast cancer [69] and acute myeloid leukemia models [70]. It remains poorly understood whether endothelial-secreted VEGF is involved in these processes. However, there is evidence that the endothelial expression of VEGF-C promotes leukemic cell survival and proliferation by activating VEGF receptor-3 on cancer cells [64]. Endothelin is an angiocrine factor which regulates the vascular tone under physiological conditions. However, it can also promote ovarian carcinoma cell proliferation [30][31]. Moreover, endothelial Delta-like 4 (DLL4), which is important for controlling blood vessels formation through activating Notch1 receptors [71], can bind to Notch3 receptors on tumor cells to support their survival [27]. Interestingly, ECs can also release angiocrine factors such as Slit2, which inhibit cancer cell proliferation and motility [59]. Future work will have to assess to which extent the release of angiocrine factors contributes to cancer cell proliferation and whether this could be targeted to enhance chemotherapy.

2.2.2. Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) and Chemoresistance

Stem cells are characterized by the capacity to self-renew and the ability to differentiate into diverse specialized cell types. It is assumed that a subpopulation of stem-like cells within tumors, known as cancer stem cells (CSCs), which exhibit characteristics of both stem cells and cancer cells, have the ability to seed tumors when transplanted into an animal host. There is increasing evidence suggesting that CSCs are resistant to conventional chemotherapy and radiation treatment. The adoption of the CSC phenotypes appears to depend on signals from neighboring cells which are capable of forming a stem cell niche [72]. Intriguingly, under physiological conditions, ECs are responsible for the self-renewal and repopulation of hematopoietic cells, for instance through Notch signaling, fibroblast growth factor-4 (FGF-4) and CXCL12 cytokine expression [73][74], indicating that at least in the bone marrow ECs are capable of forming stem cell niches. It is therefore not surprising that ECs, through their membrane-bound or angiocrine secreted factors, also play a role in the acquisition of the CSC phenotype. Indeed, tumor ECs can induce the expression of genes involved in the CSC phenotype [75]. Similar to its functions within hematopoietic stem cell niches, the expression of Notch ligands such as Jagged-1 on ECs promotes the CSC phenotype in colorectal [44] and breast cancer [45][46] by activating Notch receptors. Moreover, ECs promote a stem-like phenotype of glioma cells through the secretion of Shh and activating the Hedgehog pathway in cancer cells [58] or by secreting the basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) [33]. VEGF can be released by ECs to promote the CSC phenotype through its receptor Neuropilin-1 on skin cancer cells [65]. There is also evidence that EC-derived cytokines are involved in adopting a CSC phenotype. The most prominent examples are IL-8 and CXCL12 in glioblastoma [25] and gastric cancer [26]. Furthermore, IL-6 secreted by tumor ECs is responsible for the generation of a small sub-population of CSCs in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas [38].

CSCs are associated with chemoresistance [72], and in mouse models, cancer treatment with chemotherapy upregulated IGF1 expression in tumor ECs, which activated IGF1 receptors on cancer cells, making them resistant to chemotherapy [37]. As such, there is evidence that angiocrine factors contribute to the adoption of the CSC phenotype and potentially also to chemoresistance. Future studies are needed to elucidate whether these factors are suitable for drug targeting and how this would affect cancer progression.

2.2.3. Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition

The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) of cancer cells describes a highly dynamic and reversible process in which cancer cells of epithelial origin lose some of their typical features, like cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion, and gain migratory and invasive properties which are typical of mesenchymal cells. This is associated with profound changes in gene transcription. The EMT of cancer cells increases their metastatic potential and resistance toward chemotherapy [76]. Tumor ECs are involved in providing factors that influence EMT. For example, the EC-secreted EGF induces EMT transition in head and neck cancer cells [29]. Furthermore, ECs enhance EMT, breast cancer cell migration, invasion and metastasis by the release of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and the chemokine CCL5 [21]. At this moment, it is not yet clear whether angiocrine factors are involved in the EMT of a variety of cancer cells or only under certain conditions and cancer entities.

2.2.4. Invasion and Metastasis

Cancer invasion relies on the detachment from the basal membrane, remodeling of cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. These processes are also required for invasion into blood vessels (intravasation), which is a crucial step in the metastatic cascade. Invasion and metastasis are facilitated by the EMT of cancer cells [77]. Tumor ECs are involved in EMT (as described above) and play an active role in different aspects of invasion and metastasis.

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) Remodeling

Changes in the ECM influence the motility and invasion of tumor cells. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of proteinases that degrade the components of the ECM and thus play a major role in ECM remodeling. MMP activity is inhibited by specific tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Several cell types, including ECs, express MMPs and TIMPs in a tumor mass [43]. ECs can influence ECM remodeling either by the expression of MMPs such as MMP2 and MMP9 or by the release of cytokines like CCL2, IL-8 and CXCL16, which act in a paracrine manner by upregulating the expression of MMPs in other cell types, such as tumor cells [20]. Furthermore, endothelial DLL4-mediated Notch signaling supports tumor cell invasion due to an increased MMP-9 expression by ECs [28]. Interestingly, tumor ECs from metastatic tumors showed a higher invasive potential than tumor ECs from non-metastatic tumors, and this has been linked with higher expression levels of gelatinase/collagenase IV, MMP-2 and MMP-9 [78].

Laminins are high-molecular weight glycoproteins, which are important components of the ECM and the basal membrane. Changes in laminin expression patterns are implicated in tumor cell migration and invasion. ECs secrete laminins, and this can facilitate the migration of melanoma cells [41]. In renal cell carcinoma, laminin-α4 is highly expressed in tumor blood vessels, and this correlates with a poor prognosis [42].

In summary, the presented studies indicate that ECs are involved in ECM remodeling, but very little is known of the extent to which this is causally linked to tumor progression.

Transendothelial Migration

Metastasis requires that tumor cells enter blood or lymph vessels (intravasation), to be transported to distant sites where they again need to cross the vessel wall (extravasation). Both transmigration steps are facilitated by the binding of tumor cells to endothelial adhesion molecules. Therefore, changes in the expression levels of vascular adhesion molecules influence the efficiency of transmigration and metastasis. For example, E-selectin, which under physiological conditions is required for leukocyte adhesion to ECs, can also bind certain tumor cells [52] and thereby promote transendothelial cell migration [51][53] or the homing of circulating tumor cells in the liver [54][55]. The activation of the endothelium by inflammatory or cancer-derived factors can lead to the shedding of E-selectin into the bloodstream. This interacts with CD44 on circulating tumor cells and promotes their adhesion and migration strength [56]. E-selectin also acts as a homing receptor in the hematogenous dissemination of lung [79], prostate [80] and breast cancer [81]. The expression of E-selectin on blood vessels in the bone promotes the mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition of disseminated tumor cells and the activation of Wnt signaling, which drives the stemness of cancer cells. This results in increased bone metastasis [82]. In this regard, E-selectin inhibition may interfere with the homing of metastatic cancer cells in the lung [83] or with the survival of myeloid leukemia cells within the vascular niche [84].

Besides E-selectin, vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1) is crucial for leukocyte and tumor cell transmigration. VCAM1 is expressed by ECs and bound by tumor cells expressing integrin alpha4beta1 (VLA4). VCAM1 expression increases with inflammatory stimuli. This increases the migration of melanoma cells across activated EC layers [67] and promotes lung colonization. Endothelial Notch1 signaling upregulates VCAM1 expression, which promotes the adhesion of tumor cells to the endothelium, extravasation and lung colonization, as shown by using VCAM1-blocking antibodies [47].

Likewise, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1) expression on ECs plays a role in the adhesion of lung carcinoma to ECs [36], promoting the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells [85] and liver metastasis of colorectal cancer cells [34][35]. ICAM1 can also be shedded from the endothelium into the blood stream and interact with cancer cells to enhance their pro-metastatic potential [86][87]. Interestingly, anti-ICAM1 treatment has been proposed to interfere with tumor progression in multiple myeloma [88][89], lung [90] and breast cancer [91], showing that the targeting of angiocrine factors might be a valid therapeutic option. Furthermore, the endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells facilitates extravasation due to an increase in vascular permeability [92].

Not only membrane-bound adhesion molecules, but also EC-derived cytokines are involved in promoting cancer cell transmigration. For instance, the angiocrine factors CXCL1 and CXCL8 induce tumor cell invasion [23]. Both chemokines have also been described to enhance the transmigration and invasiveness of different cancer cell lines in 3-D collagen fiber matrix assays [24]. The angiocrine factor CCL5 promotes the downregulation of the androgen receptor (AR) in tumor cells, which accelerates the disassembly of focal adhesions, enhancing prostate cancer invasion. Hence, the inhibition of CCL5/CCR5 signaling decreased metastasis in orthotopic mouse models [22].

Tumor ECs can promote invasion and metastasis also by other factors apart from adhesion molecules and cytokines. Biglycan is a small proteoglycan, whose activity triggers tumor cell migration by nuclear factor-κB and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling. Biglycan expression was found to be upregulated only in tumor ECs of highly metastatic tumors [19]. Notably, ECs can also regulate the transendothelial migration of cancer cells through the endothelial ligand EphrinA1, which binds to Ephrin-Type-A receptor 2 (EPHA2) on cancer cells [32]. Very recently, it was shown that disseminated cancer cells secrete RNA to trigger Slit2 secretion, which promotes cancer cell migration, intravasation and metastasis [60].

Lastly, angiopoietin-2 (Ang2), which is stored in Weibel Palade bodies of ECs, is a highly interesting angiocrine factor controlling tumor progression. Ang2 levels have been related to poor prognosis, for example in melanoma [93]. Ang2 blockage showed a reduction of tumor progression, angiogenesis and metastasis [15][17][94][95][96][97]. Moreover, the blockage of the angiopoietin receptor Tie1 strongly impeded transmigration and metastasis [98]. In fact, a combination of Ang2 and Tie1 blockage improves antiangiogenic therapy [99]. Recently, a landmark study demonstrated that the Ang–Tie pathway is crucial in controlling lymphatic metastasis and that this can be prevented by antibody treatment in mouse models [16].

In summary, it became clear that several membrane-bound and soluble angiocrine factors promote the transmigration and metastasis of tumor cells. Some of these factors could even be targeted by drugs, and this resulted in promising results at least in animal models. However, we still lack knowledge about the detailed mechanism whereby cancer cells, or other cells within the tumor stroma, or even systemic factors, influence ECs so that these express higher levels of such metastasis-promoting angiocrine factors. Such understanding will however be key for future translation into clinical studies.

2.2.5. Pre-Metastatic Niche

When tumor cells travel through the blood stream, they first interact with ECs during colonization at distant sites. There is increasing evidence that tumor-derived signals change transcriptional programs in ECs and immune cells at distant sites to facilitate later metastatic spreading [100]. This concept of a pre-metastatic niche is still under debate. However, there are clear hints that ECs contribute to the homing and survival of circulating tumor cells [101][102][103]. For instance, disseminated breast tumor cells reside in close proximity to ECs at distant sites and endothelial-derived thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) maintain breast cancer cell quiescence for a long period. However, upon activation of these ECs and the subsequent angiogenic sprouting, this angiocrine effect is suppressed, allowing the formation of tumor nodules [63]. In addition, the presence of a subcutaneous tumor in mice can over-activate Notch1 signaling, not only in ECs within the tumor, but also at sites as distant as the lungs. This increases endothelial VCAM1 expression, which facilitates cancer cell homing and the formation of secondary tumors [47]. During ageing, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B expression levels increase, regulating the quiescence of the dormant disseminated tumor cells and influencing therapy resistance in bone metastasis. Therefore, bone metastasis probability increases with age [104].

These studies indicate the importance of the ECs also for the preconditioning of the metastatic niche. However, much more needs to be learnt about the factors by which a primary tumor communicates with ECs at distant sites.

2.3. Angiocrine Control of the Immune Response

The infiltration of immune cells into the TME is of striking importance for tumor progression and metastasis, as cancer cells often generate an immunosuppressive milieu [105][106]. Leucocyte infiltration into the tumor requires interactions with several EC receptors, selectins, ICAM1 and VCAM1 [107]. As described above, some of these molecules can also be used by tumor cells during transmigration.

2.3.1. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs) and Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) comprise a heterogeneous group of immunosuppressive immature myeloid cells which inhibit T cell and natural killer (NK) cell activity. In physiological conditions, myeloid progenitor cells differentiate into mature myeloid cells like macrophages and dendritic cells (DC), whereas, in pathological conditions like cancer, the differentiation of myeloid progenitor cells is impaired, leading to the formation of MDSCs [108]. The majority of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) also has an anti-inflammatory phenotype which promotes tumor progression [109]. Several chemotactic cytokines are known to recruit MDSCs and TAMs into the microenvironment [109][110][111]. Here, we only focus on angiocrine factors and how these contribute to immune cell infiltration into tumors.

Angiopoietin-2 can be secreted by tumor ECs, which leads to an autocrine activation of STAT3 signaling with secretion of CCL2 and higher expression of ICAM1 [18]. These factors promote the infiltration of CCR2-expressing monocytes into the TME [110][112]. Moreover, sustained Notch1 signaling in ECs, induced by cancer cells, drives cytokine and VCAM1 expression and the infiltration with myeloid cells, which facilitates metastasis [47]. Furthermore, E-selectin expression on ECs is required for myeloid cell infiltration in different mouse tumor models [57]. Again, this is promoted by the interaction of tumor cells with ECs, which leads to a higher E-selectin expression on tumor endothelium [57][113].

Lastly, there is increasing evidence that ECs can also impact on the polarization of recruited immune cells. In glioblastoma, the tumor endothelium was shown to be the main source of IL-6 secretion, which contributes to the adoption of an anti-inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic macrophage phenotype [39]. As such, there is still little knowledge on how ECs affect the polarization of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells and how this contributes to immunosuppression.

2.3.2. Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs)

The cytotoxic function of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) is often impaired, for example by the activation of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA4) receptors on T cells [48][49][50]. The expression of the respective ligands not only on cancer cells but also on other cells of the TME contributes to immunosuppression [114]. The role of ECs in this regard is still poorly understood. However, pre-clinal models [115] as well as recent clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma demonstrated that antiangiogenic therapy targeting VEGF synergizes with immunotherapy targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis [116][117]. It will be of outstanding importance to unravel the mechanism responsible for this. In addition, there is evidence for the angiocrine control of T cell activity in tumors. Tumor ECs can secrete Inf-γ [40] and VEGF-A [66], which influence T cell responses. In addition, the induction of T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing molecule 3 (TIM-3) expression on ECs in lymphoma inhibits CD4+ T helper cell activity by the activation of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway [61][62]. As such, there is some evidence that ECs play a role in adapting immune responses in cancer.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13112610

References

- Augustin, H.G.; Koh, G.Y. Organotypic vasculature: From descriptive heterogeneity to functional pathophysiology. Science 2017, 357.

- Carmeliet, P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 389–395.

- Khan, K.A.; Kerbel, R.S. Improving immunotherapy outcomes with anti-angiogenic treatments and vice versa. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 310–324.

- Viallard, C.; Larrivée, B. Tumor angiogenesis and vascular normalization: Alternative therapeutic targets. Angiogenesis 2017, 20, 409–426.

- Hanahan, D.; Folkman, J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell 1996, 86, 353–364.

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: Causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1745–1770.

- Folkman, J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1182–1186.

- Jayson, G.C.; Kerbel, R.; Ellis, L.M.; Harris, A.L. Antiangiogenic therapy in oncology: Current status and future directions. Lancet 2016, 388, 518–529.

- Jain, R.K. Antiangiogenesis strategies revisited: From starving tumors to alleviating hypoxia. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 605–622.

- Itatani, Y.; Kawada, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Sakai, Y. Resistance to Anti-Angiogenic Therapy in Cancer-Alterations to Anti-VEGF Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1232.

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905.

- Rafii, S.; Butler, J.M.; Ding, B.S. Angiocrine functions of organ-specific endothelial cells. Nature 2016, 529, 316–325.

- Ramasamy, S.K.; Kusumbe, A.P.; Adams, R.H. Regulation of tissue morphogenesis by endothelial cell-derived signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 148–157.

- Pasquier, J.; Ghiabi, P.; Chouchane, L.; Razzouk, K.; Rafii, S.; Rafii, A. Angiocrine endothelium: From physiology to cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 52.

- Gerald, D.; Chintharlapalli, S.; Augustin, H.G.; Benjamin, L.E. Angiopoietin-2: An attractive target for improved antiangiogenic tumor therapy. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1649–1657.

- Gengenbacher, N.; Singhal, M.; Mogler, C.; Hai, L.; Milde, L.; Pari, A.A.A.; Besemfelder, E.; Fricke, C.; Baumann, D.; Gehrs, S.; et al. Timed Ang2-Targeted Therapy Identifies the Angiopoietin-Tie Pathway as Key Regulator of Fatal Lymphogenous Metastasis. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 424–445.

- Holopainen, T.; Saharinen, P.; D’Amico, G.; Lampinen, A.; Eklund, L.; Sormunen, R.; Anisimov, A.; Zarkada, G.; Lohela, M.; Helotera, H.; et al. Effects of angiopoietin-2-blocking antibody on endothelial cell-cell junctions and lung metastasis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 461–475.

- Srivastava, K.; Hu, J.; Korn, C.; Savant, S.; Teichert, M.; Kapel, S.S.; Jugold, M.; Besemfelder, E.; Thomas, M.; Pasparakis, M.; et al. Postsurgical adjuvant tumor therapy by combining anti-angiopoietin-2 and metronomic chemotherapy limits metastatic growth. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 880–895.

- Maishi, N.; Ohba, Y.; Akiyama, K.; Ohga, N.; Hamada, J.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Alam, M.T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kawamoto, T.; Inoue, N.; et al. Tumour endothelial cells in high metastatic tumours promote metastasis via epigenetic dysregulation of biglycan. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28039.

- Wang, Y.H.; Dong, Y.Y.; Wang, W.M.; Xie, X.Y.; Wang, Z.M.; Chen, R.X.; Chen, J.; Gao, D.M.; Cui, J.F.; Ren, Z.G. Vascular endothelial cells facilitated HCC invasion and metastasis through the Akt and NF-kappaB pathways induced by paracrine cytokines. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 32, 51.

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J.; Fang, H.; Tang, L.; Chen, W.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.; Sun, Z.; Cao, L.; et al. Endothelial cells promote triple-negative breast cancer cell metastasis via PAI-1 and CCL5 signaling. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 276–288.

- Zhao, R.; Bei, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C.; Shi, F.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jing, Y.; Han, B.; et al. Endothelial cells promote metastasis of prostate cancer by enhancing autophagy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 221.

- Warner, K.A.; Miyazawa, M.; Cordeiro, M.M.; Love, W.J.; Pinsky, M.S.; Neiva, K.G.; Spalding, A.C.; Nor, J.E. Endothelial cells enhance tumor cell invasion through a crosstalk mediated by CXC chemokine signaling. Neoplasia 2008, 10, 131–139.

- Mierke, C.T.; Zitterbart, D.P.; Kollmannsberger, P.; Raupach, C.; Schlotzer-Schrehardt, U.; Goecke, T.W.; Behrens, J.; Fabry, B. Breakdown of the endothelial barrier function in tumor cell transmigration. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 2832–2846.

- McCoy, M.G.; Nyanyo, D.; Hung, C.K.; Goerger, J.P.; Zipfel, W.R.; Williams, R.M.; Nishimura, N.; Fischbach, C. Endothelial cells promote 3D invasion of GBM by IL-8-dependent induction of cancer stem cell properties. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9069.

- Hayakawa, Y.; Ariyama, H.; Stancikova, J.; Sakitani, K.; Asfaha, S.; Renz, B.W.; Dubeykovskaya, Z.A.; Shibata, W.; Wang, H.; Westphalen, C.B.; et al. Mist1 Expressing Gastric Stem Cells Maintain the Normal and Neoplastic Gastric Epithelium and Are Supported by a Perivascular Stem Cell Niche. Cancer Cell 2015, 28, 800–814.

- Indraccolo, S.; Minuzzo, S.; Masiero, M.; Pusceddu, I.; Persano, L.; Moserle, L.; Reboldi, A.; Favaro, E.; Mecarozzi, M.; Di Mario, G.; et al. Cross-talk between tumor and endothelial cells involving the Notch3-Dll4 interaction marks escape from tumor dormancy. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 1314–1323.

- Huang, Q.B.; Ma, X.; Li, H.Z.; Ai, Q.; Liu, S.W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Fan, Y.; Ni, D.; Wang, B.J.; et al. Endothelial Delta-like 4 (DLL4) promotes renal cell carcinoma hematogenous metastasis. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 3066–3075.

- Zhang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Lauxen, I.S.; Filho, M.S.; Nor, J.E. Endothelial cell-secreted EGF induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition and endows head and neck cancer cells with stem-like phenotype. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2869–2881.

- Bagnato, A.; Salani, D.; Di Castro, V.; Wu-Wong, J.R.; Tecce, R.; Nicotra, M.R.; Venuti, A.; Natali, P.G. Expression of endothelin 1 and endothelin A receptor in ovarian carcinoma: Evidence for an autocrine role in tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 720–727.

- Grant, K.; Loizidou, M.; Taylor, I. Endothelin-1: A multifunctional molecule in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 88, 163–166.

- Locard-Paulet, M.; Lim, L.; Veluscek, G.; McMahon, K.; Sinclair, J.; van Weverwijk, A.; Worboys, J.D.; Yuan, Y.; Isacke, C.M.; Jorgensen, C. Phosphoproteomic analysis of interacting tumor and endothelial cells identifies regulatory mechanisms of transendothelial migration. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra15.

- Fessler, E.; Borovski, T.; Medema, J.P. Endothelial cells induce cancer stem cell features in differentiated glioblastoma cells via bFGF. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 157.

- Benedicto, A.; Romayor, I.; Arteta, B. Role of liver ICAM-1 in metastasis. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 3883–3892.

- Benedicto, A.; Herrero, A.; Romayor, I.; Marquez, J.; Smedsrod, B.; Olaso, E.; Arteta, B. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell ICAM-1 mediated tumor/endothelial crosstalk drives the development of liver metastasis by initiating inflammatory and angiogenic responses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13111.

- Finzel, A.H.; Reininger, A.J.; Bode, P.A.; Wurzinger, L.J. ICAM-1 supports adhesion of human small-cell lung carcinoma to endothelial cells. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2004, 21, 185–189.

- Cao, Z.; Scandura, J.M.; Inghirami, G.G.; Shido, K.; Ding, B.S.; Rafii, S. Molecular Checkpoint Decisions Made by Subverted Vascular Niche Transform Indolent Tumor Cells into Chemoresistant Cancer Stem Cells. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 110–126.

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Warner, K.A.; Dong, Z.; Imai, A.; Nor, C.; Ward, B.B.; Helman, J.I.; Taichman, R.S.; Bellile, E.L.; McCauley, L.K.; et al. Endothelial interleukin-6 defines the tumorigenic potential of primary human cancer stem cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 2845–2857.

- Wang, Q.; He, Z.; Huang, M.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Duan, H.; Ma, P.; Zhang, L.; Zamvil, S.S.; et al. Vascular niche IL-6 induces alternative macrophage activation in glioblastoma through HIF-2alpha. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 559.

- Demaria, O.; De Gassart, A.; Coso, S.; Gestermann, N.; Di Domizio, J.; Flatz, L.; Gaide, O.; Michielin, O.; Hwu, P.; Petrova, T.V.; et al. STING activation of tumor endothelial cells initiates spontaneous and therapeutic antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15408–15413.

- Lugassy, C.; Christensen, L.; Le Charpentier, M.; Faure, E.; Escande, J.P. Angio-tumoral laminin in murine tumors derived from human melanoma cell lines. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural observations. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 1998, 30, 231–237.

- Wragg, J.W.; Finnity, J.P.; Anderson, J.A.; Ferguson, H.J.; Porfiri, E.; Bhatt, R.I.; Murray, P.G.; Heath, V.L.; Bicknell, R. MCAM and LAMA4 Are Highly Enriched in Tumor Blood Vessels of Renal Cell Carcinoma and Predict Patient Outcome. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2314–2326.

- Foda, H.D.; Zucker, S. Matrix metalloproteinases in cancer invasion, metastasis and angiogenesis. Drug Discov. Today 2001, 6, 478–482.

- Lu, J.; Ye, X.; Fan, F.; Xia, L.; Bhattacharya, R.; Bellister, S.; Tozzi, F.; Sceusi, E.; Zhou, Y.; Tachibana, I.; et al. Endothelial cells promote the colorectal cancer stem cell phenotype through a soluble form of Jagged-1. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 171–185.

- Ghiabi, P.; Jiang, J.; Pasquier, J.; Maleki, M.; Abu-Kaoud, N.; Rafii, S.; Rafii, A. Endothelial cells provide a notch-dependent pro-tumoral niche for enhancing breast cancer survival, stemness and pro-metastatic properties. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112424.

- Jiang, H.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wei, H.; Shi, W.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Ou, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Jagged1-Notch1-deployed tumor perivascular niche promotes breast cancer stem cell phenotype through Zeb1. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5129.

- Wieland, E.; Rodriguez-Vita, J.; Liebler, S.S.; Mogler, C.; Moll, I.; Herberich, S.E.; Espinet, E.; Herpel, E.; Menuchin, A.; Chang-Claude, J.; et al. Endothelial Notch1 Activity Facilitates Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 355–367.

- Iwai, Y.; Ishida, M.; Tanaka, Y.; Okazaki, T.; Honjo, T.; Minato, N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 12293–12297.

- Dong, H.; Strome, S.E.; Salomao, D.R.; Tamura, H.; Hirano, F.; Flies, D.B.; Roche, P.C.; Lu, J.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 793–800.

- LaGier, A.J.; Pober, J.S. Immune accessory functions of human endothelial cells are modulated by overexpression of B7-H1 (PDL1). Hum. Immunol. 2006, 67, 568–578.

- Laferriere, J.; Houle, F.; Taher, M.M.; Valerie, K.; Huot, J. Transendothelial migration of colon carcinoma cells requires expression of E-selectin by endothelial cells and activation of stress-activated protein kinase-2 (SAPK2/p38) in the tumor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 33762–33772.

- Woodward, J. Crossing the endothelium: E-selectin regulates tumor cell migration under flow conditions. Cell. Adh. Migr. 2008, 2, 151–152.

- Tremblay, P.L.; Auger, F.A.; Huot, J. Regulation of transendothelial migration of colon cancer cells by E-selectin-mediated activation of p38 and ERK MAP kinases. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6563–6573.

- Brodt, P.; Fallavollita, L.; Bresalier, R.S.; Meterissian, S.; Norton, C.R.; Wolitzky, B.A. Liver endothelial E-selectin mediates carcinoma cell adhesion and promotes liver metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 71, 612–619.

- Khatib, A.M.; Kontogiannea, M.; Fallavollita, L.; Jamison, B.; Meterissian, S.; Brodt, P. Rapid induction of cytokine and E-selectin expression in the liver in response to metastatic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 1356–1361.

- Kang, S.A.; Blache, C.A.; Bajana, S.; Hasan, N.; Kamal, M.; Morita, Y.; Gupta, V.; Tsolmon, B.; Suh, K.S.; Gorenstein, D.G.; et al. The effect of soluble E-selectin on tumor progression and metastasis. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 331.

- Borsig, L. Selectins in cancer immunity. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 648–655.

- Yan, G.N.; Yang, L.; Lv, Y.F.; Shi, Y.; Shen, L.L.; Yao, X.H.; Guo, Q.N.; Zhang, P.; Cui, Y.H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Endothelial cells promote stem-like phenotype of glioma cells through activating the Hedgehog pathway. J. Pathol. 2014, 234, 11–22.

- Brantley-Sieders, D.M.; Dunaway, C.M.; Rao, M.; Short, S.; Hwang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Li, D.; Jiang, A.; Shyr, Y.; Wu, J.Y.; et al. Angiocrine factors modulate tumor proliferation and motility through EphA2 repression of Slit2 tumor suppressor function in endothelium. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 976–987.

- Tavora, B.; Mederer, T.; Wessel, K.J.; Ruffing, S.; Sadjadi, M.; Missmahl, M.; Ostendorf, B.N.; Liu, X.; Kim, J.Y.; Olsen, O.; et al. Tumoural activation of TLR3-SLIT2 axis in endothelium drives metastasis. Nature 2020, 586, 299–304.

- Wu, F.H.; Yuan, Y.; Li, D.; Lei, Z.; Song, C.W.; Liu, Y.Y.; Li, B.; Huang, B.; Feng, Z.H.; Zhang, G.M. Endothelial cell-expressed Tim-3 facilitates metastasis of melanoma cells by activating the NF-kappaB pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 24, 693–699.

- Huang, X.; Bai, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, M.; Tang, D.; Tao, S.; Zhu, T.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Lymphoma endothelium preferentially expresses Tim-3 and facilitates the progression of lymphoma by mediating immune evasion. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 505–520.

- Ghajar, C.M.; Peinado, H.; Mori, H.; Matei, I.R.; Evason, K.J.; Brazier, H.; Almeida, D.; Koller, A.; Hajjar, K.A.; Stainier, D.Y.; et al. The perivascular niche regulates breast tumour dormancy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 807–817.

- Dias, S.; Choy, M.; Alitalo, K.; Rafii, S. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-C signaling through FLT-4 (VEGFR-3) mediates leukemic cell proliferation, survival, and resistance to chemotherapy. Blood 2002, 99, 2179–2184.

- Beck, B.; Driessens, G.; Goossens, S.; Youssef, K.K.; Kuchnio, A.; Caauwe, A.; Sotiropoulou, P.A.; Loges, S.; Lapouge, G.; Candi, A.; et al. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature 2011, 478, 399–403.

- Voron, T.; Colussi, O.; Marcheteau, E.; Pernot, S.; Nizard, M.; Pointet, A.L.; Latreche, S.; Bergaya, S.; Benhamouda, N.; Tanchot, C.; et al. VEGF-A modulates expression of inhibitory checkpoints on CD8+ T cells in tumors. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 139–148.

- Klemke, M.; Weschenfelder, T.; Konstandin, M.H.; Samstag, Y. High affinity interaction of integrin alpha4beta1 (VLA-4) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) enhances migration of human melanoma cells across activated endothelial cell layers. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 212, 368–374.

- Tamura, R.; Tanaka, T.; Akasaki, Y.; Murayama, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Sasaki, H. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in the hypoxic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment: Perspectives for therapeutic implications. Med. Oncol. 2019, 37, 2.

- Liang, Y.; Brekken, R.A.; Hyder, S.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces proliferation of breast cancer cells and inhibits the anti-proliferative activity of anti-hormones. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 905–919.

- Koistinen, P.; Siitonen, T.; Mantymaa, P.; Saily, M.; Kinnula, V.; Savolainen, E.R.; Soini, Y. Regulation of the acute myeloid leukemia cell line OCI/AML-2 by endothelial nitric oxide synthase under the control of a vascular endothelial growth factor signaling system. Leukemia 2001, 15, 1433–1441.

- Potente, M.; Gerhardt, H.; Carmeliet, P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 2011, 146, 873–887.

- Batlle, E.; Clevers, H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1124–1134.

- Butler, J.M.; Nolan, D.J.; Vertes, E.L.; Varnum-Finney, B.; Kobayashi, H.; Hooper, A.T.; Seandel, M.; Shido, K.; White, I.A.; Kobayashi, M.; et al. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 251–264.

- Ramalingam, P.; Poulos, M.G.; Butler, J.M. Regulation of the hematopoietic stem cell lifecycle by the endothelial niche. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2017, 24, 289–299.

- Wang, R.; Bhattacharya, R.; Ye, X.; Fan, F.; Boulbes, D.R.; Xia, L.; Ellis, L.M. Endothelial cells activate the cancer stem cell-associated NANOGP8 pathway in colorectal cancer cells in a paracrine fashion. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 1023–1034.

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New insights into the mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and implications for cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 69–84.

- Pastushenko, I.; Blanpain, C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 212–226.

- Ohga, N.; Ishikawa, S.; Maishi, N.; Akiyama, K.; Hida, Y.; Kawamoto, T.; Sadamoto, Y.; Osawa, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Kondoh, M.; et al. Heterogeneity of tumor endothelial cells: Comparison between tumor endothelial cells isolated from high- and low-metastatic tumors. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 1294–1307.

- Martin-Satue, M.; Marrugat, R.; Cancelas, J.A.; Blanco, J. Enhanced expression of alpha(1,3)-fucosyltransferase genes correlates with E-selectin-mediated adhesion and metastatic potential of human lung adenocarcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 1544–1550.

- Dimitroff, C.J.; Lechpammer, M.; Long-Woodward, D.; Kutok, J.L. Rolling of human bone-metastatic prostate tumor cells on human bone marrow endothelium under shear flow is mediated by E-selectin. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5261–5269.

- Carrascal, M.A.; Silva, M.; Ferreira, J.A.; Azevedo, R.; Ferreira, D.; Silva, A.M.N.; Ligeiro, D.; Santos, L.L.; Sackstein, R.; Videira, P.A. A functional glycoproteomics approach identifies CD13 as a novel E-selectin ligand in breast cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2018, 1862, 2069–2080.

- Esposito, M.; Mondal, N.; Greco, T.M.; Wei, Y.; Spadazzi, C.; Lin, S.C.; Zheng, H.; Cheung, C.; Magnani, J.L.; Lin, S.H.; et al. Bone vascular niche E-selectin induces mesenchymal-epithelial transition and Wnt activation in cancer cells to promote bone metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 627–639.

- Hiratsuka, S.; Goel, S.; Kamoun, W.S.; Maru, Y.; Fukumura, D.; Duda, D.G.; Jain, R.K. Endothelial focal adhesion kinase mediates cancer cell homing to discrete regions of the lungs via E-selectin up-regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3725–3730.

- Barbier, V.; Erbani, J.; Fiveash, C.; Davies, J.M.; Tay, J.; Tallack, M.R.; Lowe, J.; Magnani, J.L.; Pattabiraman, D.R.; Perkins, A.C.; et al. Endothelial E-selectin inhibition improves acute myeloid leukaemia therapy by disrupting vascular niche-mediated chemoresistance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2042.

- Rosette, C.; Roth, R.B.; Oeth, P.; Braun, A.; Kammerer, S.; Ekblom, J.; Denissenko, M.F. Role of ICAM1 in invasion of human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2005, 26, 943–950.

- Witkowska, A.M.; Borawska, M.H. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1): An overview. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2004, 15, 91–98.

- Maruo, Y.; Gochi, A.; Kaihara, A.; Shimamura, H.; Yamada, T.; Tanaka, N.; Orita, K. ICAM-1 expression and the soluble ICAM-1 level for evaluating the metastatic potential of gastric cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 100, 486–490.

- Sherbenou, D.W.; Su, Y.; Behrens, C.R.; Aftab, B.T.; Perez de Acha, O.; Murnane, M.; Bearrows, S.C.; Hann, B.C.; Wolf, J.L.; Martin, T.G.; et al. Potent Activity of an Anti-ICAM1 Antibody-Drug Conjugate against Multiple Myeloma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 6028–6038.

- Wichert, S.; Juliusson, G.; Johansson, A.; Sonesson, E.; Teige, I.; Wickenberg, A.T.; Frendeus, B.; Korsgren, M.; Hansson, M. A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 clinical trial evaluating disease response following treatment with BI-505, a human anti-intercellular adhesion molecule-1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with smoldering multiple myeloma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171205.

- Lin, Y.C.; Shun, C.T.; Wu, M.S.; Chen, C.C. A novel anticancer effect of thalidomide: Inhibition of intercellular adhesion molecule-1-mediated cell invasion and metastasis through suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7165–7173.

- Guo, P.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Jia, D.; Yang, J.; Dillon, D.A.; Zurakowski, D.; Mao, H.; Moses, M.A.; Auguste, D.T. ICAM-1 as a molecular target for triple negative breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14710–14715.

- Wolf, M.J.; Hoos, A.; Bauer, J.; Boettcher, S.; Knust, M.; Weber, A.; Simonavicius, N.; Schneider, C.; Lang, M.; Sturzl, M.; et al. Endothelial CCR2 signaling induced by colon carcinoma cells enables extravasation via the JAK2-Stat5 and p38MAPK pathway. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 91–105.

- Helfrich, I.; Edler, L.; Sucker, A.; Thomas, M.; Christian, S.; Schadendorf, D.; Augustin, H.G. Angiopoietin-2 levels are associated with disease progression in metastatic malignant melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 1384–1392.

- Daly, C.; Eichten, A.; Castanaro, C.; Pasnikowski, E.; Adler, A.; Lalani, A.S.; Papadopoulos, N.; Kyle, A.H.; Minchinton, A.I.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; et al. Angiopoietin-2 functions as a Tie2 agonist in tumor models, where it limits the effects of VEGF inhibition. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 108–118.

- Oliner, J.; Min, H.; Leal, J.; Yu, D.; Rao, S.; You, E.; Tang, X.; Kim, H.; Meyer, S.; Han, S.J.; et al. Suppression of angiogenesis and tumor growth by selective inhibition of angiopoietin-2. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 507–516.

- Coutelle, O.; Schiffmann, L.M.; Liwschitz, M.; Brunold, M.; Goede, V.; Hallek, M.; Kashkar, H.; Hacker, U.T. Dual targeting of Angiopoetin-2 and VEGF potentiates effective vascular normalisation without inducing empty basement membrane sleeves in xenograft tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 495–503.

- Park, J.S.; Kim, I.K.; Han, S.; Park, I.; Kim, C.; Bae, J.; Oh, S.J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.H.; Woo, D.C.; et al. Normalization of Tumor Vessels by Tie2 Activation and Ang2 Inhibition Enhances Drug Delivery and Produces a Favorable Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 157–158.

- Singhal, M.; Gengenbacher, N.; La Porta, S.; Gehrs, S.; Shi, J.; Kamiyama, M.; Bodenmiller, D.M.; Fischl, A.; Schieb, B.; Besemfelder, E.; et al. Preclinical validation of a novel metastasis-inhibiting Tie1 function-blocking antibody. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e11164.

- D’Amico, G.; Korhonen, E.A.; Anisimov, A.; Zarkada, G.; Holopainen, T.; Hagerling, R.; Kiefer, F.; Eklund, L.; Sormunen, R.; Elamaa, H.; et al. Tie1 deletion inhibits tumor growth and improves angiopoietin antagonist therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 824–834.

- Peinado, H.; Zhang, H.; Matei, I.R.; Costa-Silva, B.; Hoshino, A.; Rodrigues, G.; Psaila, B.; Kaplan, R.N.; Bromberg, J.F.; Kang, Y.; et al. Pre-metastatic niches: Organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 302–317.

- Barbazan, J.; Alonso-Alconada, L.; Elkhatib, N.; Geraldo, S.; Gurchenkov, V.; Glentis, A.; van Niel, G.; Palmulli, R.; Fernandez, B.; Viano, P.; et al. Liver Metastasis Is Facilitated by the Adherence of Circulating Tumor Cells to Vascular Fibronectin Deposits. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 3431–3441.

- Lu, Y.; Yu, T.; Liang, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, J.; Shao, J.; Gao, Y.; Yu, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; et al. Nitric oxide inhibits hetero-adhesion of cancer cells to endothelial cells: Restraining circulating tumor cells from initiating metastatic cascade. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4344.

- Rejniak, K.A. Circulating Tumor Cells: When a Solid Tumor Meets a Fluid Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 936, 93–106.

- Singh, A.; Veeriah, V.; Xi, P.; Labella, R.; Chen, J.; Romeo, S.G.; Ramasamy, S.K.; Kusumbe, A.P. Angiocrine signals regulate quiescence and therapy resistance in bone metastasis. JCI Insight 2019, 4.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Chen, D.S.; Mellman, I. Oncology meets immunology: The cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 2013, 39, 1–10.

- Al-Soudi, A.; Kaaij, M.H.; Tas, S.W. Endothelial cells: From innocent bystanders to active participants in immune responses. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 951–962.

- Veglia, F.; Perego, M.; Gabrilovich, D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 108–119.

- Franklin, R.A.; Li, M.O. Ontogeny of Tumor-associated Macrophages and Its Implication in Cancer Regulation. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 20–34.

- Qian, B.Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Kitamura, T.; Zhang, J.; Campion, L.R.; Kaiser, E.A.; Snyder, L.A.; Pollard, J.W. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature 2011, 475, 222–225.

- Ostuni, R.; Kratochvill, F.; Murray, P.J.; Natoli, G. Macrophages and cancer: From mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 229–239.

- Serbina, N.V.; Pamer, E.G. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 311–317.

- Häuselmann, I.; Roblek, M.; Protsyuk, D.; Huck, V.; Knopfova, L.; Grässle, S.; Bauer, A.T.; Schneider, S.W.; Borsig, L. Monocyte Induction of E-Selectin-Mediated Endothelial Activation Releases VE-Cadherin Junctions to Promote Tumor Cell Extravasation in the Metastasis Cascade. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 5302–5312.

- Tormoen, G.W.; Crittenden, M.R.; Gough, M.J. Role of the immunosuppressive microenvironment in immunotherapy. Adv. Radiat. Oncol. 2018, 3, 520–526.

- Allen, E.; Jabouille, A.; Rivera, L.B.; Lodewijckx, I.; Missiaen, R.; Steri, V.; Feyen, K.; Tawney, J.; Hanahan, D.; Michael, I.P.; et al. Combined antiangiogenic and anti-PD-L1 therapy stimulates tumor immunity through HEV formation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9.

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulieres, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127.

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodriguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301.