1. Introduction

Although vaccination is recognised as the top public health achievement of the twentieth century, saving millions of individual lives and, importantly, prolonging life expectancy [

1], the general consensus about its beneficence has not been reached among people [

2,

3,

4]. In countries with well-established immunisation programmes, vaccines are said to be “victims of their own success”, because low incidences of diseases now prevented with vaccines has diminished the experience of historical burdens of several devastating communicable diseases [

2]. Nowadays, a wide variety of opinions about vaccination exist; some people are against it in principle, others are against its mandatoriness or against the involvement of the state; yet others are just concerned about its safety issues and maybe prefer alternative vaccination programmes or delayed vaccination [

5,

6,

7]. Therefore, different terms for parents who lack compliance with vaccination are used, though not consistently [

6,

8,

9,

10]. The term “anti-vaxxers” refers to a broad group of people, who are against vaccination for whatever reason [

6]. Terms “vaccine-refusal” or “vaccine-reluctancy” represent the anti-vaccination extreme and define individuals who fail to vaccinate themselves or their children for different reasons [

6,

11]. “Vaccine-hesitancy” is a term that covers the continuum of opinions between pro- and anti-vaccination extremes. Vaccine-hesitant individuals do not refuse vaccination in principle but are concerned about its safety/efficiency or maybe just prefer alternative vaccination schedules [

2,

6,

12]. In our review, we use the term “vaccine-hesitant parents”, because it applies to the whole spectrum of different opinions about vaccination.

The number of vaccine-hesitant people is high, with up to 90% of people expressing hesitancy in at least one aspect of vaccination, using the World Health Organisation Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (WHO SAGE) Vaccine Hesitancy Scale [

13,

14,

15]. However, a large-scale retrospective study, published in 2020 in The Lancet, reported that confidence in the importance, safety and effectiveness of vaccines improved in some countries across the world and fell in the others in the last few years [

16]. The percentage of vaccine-refusing people is lower than vaccine-hesitant and is estimated to around 5% [

17]. Vaccine hesitancy is, especially in high-income countries, one of the most important reasons for lower immunisation coverage, which results in outbreaks of vaccine-controllable diseases [

2,

7,

18,

19]. Due to high contingency, several measles outbreaks across Europe and North America in recent years raised attention to low vaccination coverage in particular countries [

15,

20,

21]. WHO declared vaccine hesitancy, defined as the reluctance or refusal to vaccine despite the availability of vaccines, as one of the world’s top ten global health threats in 2019 [

22]. There are many reasons why parents might be hesitant or refuse to vaccinate their children, including worries about a vaccine’s safety and the maturity of a child’s immune system, absence of the disease in a certain population, motives of pharmaceutical industry, diminished trust in public health system, misinformation, perception of coercion, religious beliefs, etc. [

2,

7].

Preventive vaccination is a complex topic, because it involves an individual, doctor–patient perspective, as well as a public health perspective. At the level of society, the major ethical dilemmas concern vaccine development and safety issues [

23,

24,

25], fair global vaccine allocation and development [

26], vaccination for travellers and workers [

21,

27,

28] and ethical justification of measures to maintain herd immunity of the population [

5,

15,

19]. At the level of an individual, there can be conflicts between respect for parents’ autonomy, the child’s best interest and just contribution to herd immunity [

5,

29]. Although every country has its own vaccination policy and recommendations, each situation when treating children of vaccine-hesitant parents is unique and needs an individual and personal approach [

30,

31].

In this article, we develop a systematic approach by the four principles of biomedical ethics (the respect for individual’s autonomy, the principles of non-maleficence, beneficence and justice), first introduced in 1979 by Childress and Beauchamp, to be applicable as the ethical framework to facilitate the decision-making process. After the first release, the principles-based approach quickly became a dominant framework for American and also global bioethics [

32,

33]. However, there are many possible ways of approaching bioethical problems and none of them is ideal. Despite some criticism regarding the four-principles approach [

34,

35,

36,

37], the framework is widely accepted and compatible with a variety of moral theories [

38]. Although the approach is basically simple, as ethics should be in order to serve different profiles of people, it can also be complexified [

38]. Beauchamp and Childress claim that their framework captures major moral considerations that are essential starting points for biomedical ethics, but only the process of specification and balancing broad principles and rules leads to the concrete moral judgments [

39]. The four principles theory, as also other bioethical theories, should maybe not be understood as action-guiding but rather as procedures by which one’s decisions can achieve a reasonable degree of moral justification [

40]. The approach to ethics of vaccination, developed in this paper, could; therefore, help healthcare providers and also decision-makers at various levels to better understand ethical issues and values at stake, and suggest them a more systematic and better defined way of ethical deliberation to reach best possible solutions [

31,

41].

Thus, we aimed to apply a framework for ethical analysis of vaccination in childhood basing on the four principles of biomedical ethics to provide a comprehensive and applicable model on how to address the ethical aspects of vaccination at both individual and societal levels. The paper is primarily meant not to innovate or deepen the theory behind the ethics of vaccination, but to comprehensively explore the ethical dilemmas regarding childhood vaccination. This might help especially the healthcare workers, which daily encounter dilemmas regarding vaccination in their practices, to better understand the subject and get support for their work.

2. Respect for Autonomy

The principle of respect for autonomy has a variety of interpretations. In clinical ethics it is usually understood as a right of an individual patient or research subject to decide about themselves according to their own principles, which gives them also responsibilities for the possible outcomes [

41,

42,

43,

44]. This principle is a fundamental ethical and political concept especially in countries with western tradition over the last 50 years [

41,

42,

43]. However, it is not an absolute principle and should not represent present-day individualism, as some critics have argued, but should always be balanced by other principles, taking into account social responsibilities and communal goals [

39]. In practice, autonomy is exercised through informed consent or informed refusal [

41,

42]. There are at least four mandatory criteria that need to be fulfilled for its legitimacy: decision making capacity of a patient, adequate disclosure of information with its adequate understanding and voluntariness [

41,

45,

46]. In the paediatric setting, when patients do not have appropriate decisional capacity for informed consent, two other important concepts were endorsed by the policy statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics (published in 1995, reaffirmed in 2016): parental permission and child’s assent [

47,

48]. The latter gains its value with child’s maturation, until full decision making capacity is assigned to an adolescent or young adult [

47,

49]. In the ethics of vaccination, the degree of respect for parents’ autonomy is one of the key issues at stake. In many cases, vaccine hesitancy or refusal is a consequence of insufficient or inappropriate information, its misunderstanding or presence of manipulation, which constrain one’s autonomy [

2,

31]. In this section, we will go through the main criteria for autonomous decision making from the perspective of vaccination.

2.1. Decision Making Capacity

To make an informed consent or refusal, individuals need a minimum level of capacity to receive information, understand it, make their choices and articulate them. However, each person is owed disclosure of information according to their own health literacy, which is further discussed in the next paragraph. In contrast to competency, which is determined by court, capacity is task specific—depends on a context [

41]. Regarding vaccination, it is mostly parents who make decisions on behalf of their children, because the majority of vaccinations are scheduled in early childhood [

41,

50]. However, because a state also has a duty and interest in protecting a child from harm, it can challenge parental authority in situations in which a child is put at risk (the doctrine of parens patriae) [

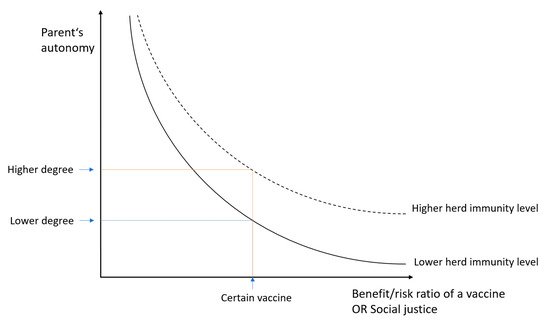

47]. The degree of parent’s autonomy depends on a type of planned intervention (or a type of vaccine); the higher a ratio between benefit and burden (having in mind the principles of beneficence and non-maleficence), the less decisive parents’ autonomy is, and vice versa (). The role of parental autonomy is also affected by the principle of justice (in the context of vaccination, the need to contribute to the herd immunity in a population is its important part, which will be dealt with in the Discussion section).

Figure 1. Relation between parents’ autonomy and benefit:risk ratio of a vaccine (or social justice). The curve can be moved upwards in case of a good society immunisation level, which could allow a higher degree of parents’ autonomy and non-medical exemptions from vaccination.

2.2. Disclosure of Information and Adequate Understanding

For parental permission, adequate explanation which parents or their surrogates understand needs to be provided [

47]. Lack of information, misunderstanding or false information are common causes for vaccine hesitancy or refusal [

2,

4]. Studies have shown that parents who delayed or refused vaccines do not consider the child’s health care provider as a reliable information source and are more likely to seek vaccine information on the Internet [

2,

30,

51]. Prior to burdening parents with responsibility, which comes together with autonomy, it is the responsibility of accountable public health structures and its professionals and also of individual clinicians to provide adequate, reliable and understandable information about vaccination [

52]. Improved parents’ education and their adequate informing play a key role in the promotion of vaccination and enable the parents to make responsible immunisation decisions [

53,

54,

55]. Trust of the society in scientific evidence about vaccines, in the health care system and in vaccination policy is crucial, but not self-evident. It needs to be restored and maintained by provision of transparent information about vaccines, consistent attitudes of scientists and health care professionals and by the government taking responsibility for individuals affected by side effects [

29,

56]. Confidence is both a means and a result of ethically justified and efficient public health activities [

56]. Additionally, a trustful relationship between medical personnel and parents is also important. Listening carefully to parent’s concerns and provision of clear information about risks and benefits of vaccination can help hesitant parents to understand principles of vaccination and, with their consent, to obviate ethical dilemmas of vaccine refusal [

31,

56]. However, because time meant for consultation with parents prior to vaccination is limited and it is often not possible to address all the parents’ concerns, a systematic approach is preferable (e.g., by social media or in organized forms of education about vaccination) [

57].

2.3. Voluntariness

A voluntary decision and absence of manipulation or coercion are an essential part of informed consent, though many factors may influence patient’s position (e.g., previous experience, social myths, opinion of family members and friends, clinician’s persuasion, legal obligations and constitutional pressures) [

41,

47]. Many of them do not threaten autonomous choice, even more, they are a fundamental part of decision making (so called “noncontrolling influence”) [

41]. But some factors may limit one’s autonomy (“controlling influence”), and they also appear among reasons for vaccination hesitancy (i.e., conspiracy theories and family members’ pressure) [

2,

41]. These reasons need to be recognised and, if possible, avoided. A question arises, what is the relationship between autonomy and authority of behaviour prescribing organizations and traditions (i.e., government, religion, medical authority). Some claim that they are incompatible, but others see a conflict only when authority has not been properly delegated or accepted [

41,

58].

2.4. Conscientious Objection of Parents and Medical Personnel

If all the above criteria for informed consent (or refusal) are met, parents can in some countries object to vaccination on personal, conscientious grounds (i.e., for religious, moral, or philosophical reasons (“non-medical exemptions”)) [

3,

41,

51,

59]. It is questionable if parents should be entitled to assert conscientious objection to vaccination, and, if so, what constraints this entitlement should be subject to [

60,

61]. Clarke et al. states that conscientious objection to vaccination for severe or highly contagious diseases is justified only in cases when the rate of its assertion does not threaten herd immunity [

60]. In 2019 there were 45 states in the USA which allowed non-medical exemptions from immunisation [

62]. Among European countries with mandatory vaccination policy, only two of them allowed non-medical exemptions in 2020 [

63].

On the other hand, there also are physicians’ and other medical personnel’s autonomy [

41,

64,

65]. It is exercised through right to refuse certain procedures or treatments on conscientious grounds. Because conscientious objection can contradict physician’s duties and may even limit patient’s access to health care, this right is subject to certain restrictions [

64,

66]. Some medical practitioners across the world refuse to treat children that are not vaccinated. Because this can affect access of unvaccinated children to health care, justification of applying conscientious objection in this case is debatable [

67,

68].