1. Introduction

Pollination is an essential ecosystem service and is crucial for guaranteeing global food security [

1], with its economic importance estimated at USD 235–577 billion annually [

2]. Bees are the most important crop pollinators worldwide [

3], with

Apis mellifera being the main managed pollinator species for crops around the world [

4]. However, several crops demand specific solitary bees to guarantee efficient pollination and fruit set [

5,

6,

7], and indeed, an overall high diversity of native bee pollinators enhances crop yield [

8,

9].

Bees are typically diurnal but approximately 1% of described species (

ca. 250) have crepuscular and/or nocturnal activity. Crepuscular bees fly pre-sunrise and post-sunset, and truly nocturnal bees fly all night or for most of the night [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. This behavior has arisen independently in four of the seven bee families: Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, and Halictidae [

13,

15]. It is hypothesized that these bees developed nocturnal habits to escape diurnal competition for floral resources and to avoid enemies such as kleptoparasites, which are less active at night [

11,

15,

16,

17].

Foraging at night and during twilight is thus likely to be beneficial, as flowers are often rich in pollen and nectar early in the morning before being exploited by diurnal flower visitors [

18], as well as late into the evening before nocturnal visitors arrive, providing a “competitor free space” [

12,

16]. In addition, by mainly visiting plant species with abundant floral rewards available, they would spend little time searching for host plants [

19,

20].

Most crepuscular/nocturnal bees (hereafter referred to as nocturnal bees) occur in Neotropical regions and are widespread, mainly in South America [

21]. The biology of nocturnal bees is poorly studied due to a preferential bias towards studying diurnal insects. One of the most studied and common nocturnal bee genera is

Megalopta (Halictidae), which currently accounts for 32 species distributed from South Mexico to Argentina [

22,

23].

Megalopta bees build their nests in cavities within dead wood, and in some species more than one female per nest was recorded, suggesting a facultative social behavior [

24,

25,

26]. The other abundant nocturnal bee genus,

Ptiloglossa (Colletidae), has 55 described species occurring from the Southern United States to Argentina [

21,

27]. These bees dig tunnels in the ground to build their nests [

28,

29,

30]. The genus

Xylocopa has some records related to its nocturnal representatives, as

X.

tranquebarica from Asia [

31]. Besides these, there are other genera of nocturnal bees, such as

Megommation,

Zikanapis, and

Xenoglossa [

15,

32] (). There are species with facultative nocturnal behavior that forage during the day but occasionally have also been reported at night, among them

Apis dorsata,

A.

mellifera adansonii, and other

Xylocopa species [

12,

33].

Figure 1. Nocturnal bees: (A) Megalopta aeneicollis, (B) Ptiloglossa latecalcarata, (C) Megommation insigne, (D) Megalopta sodalis.

These bees visit a high number of plant species, among them crops [

34]. The pollination efficiency of nocturnal bees was recently shown for Brazilian crops of different families, such as Anacardiaceae (

Spondias mombin), Myrtaceae (

Campomanesia phaea), and Sapindaceae (

Paullinia cupana) [

18,

35,

36,

37], but they are potential pollinators of other crops as well [

38,

39]. Here, we review the literature on nocturnal bees: how they find flowers, their pollinator traits and host plants, and assess the crop pollination effectiveness of this neglected group. We then address perspectives on how to provide appropriate habitats to improve the presence of nocturnal bees around cropping areas to facilitate pollination.

2. How Do Nocturnal Bees Find Flowers in the Darkness?

Bees use visual (shape, brightness, and color) as well as chemical (scent) floral cues to find flowers and to obtain food resources such as nectar and pollen [

40,

41,

42]. As nocturnal bees have a very restricted period of activity to collect their food resources (

ca. 1–2 h), one might expect that these bees need to be very efficient at finding flowers. Compared to diurnal bees, nocturnal bees have several visual adaptations to cope with low light intensities. They typically have larger apposition compound eyes and ocelli [

10,

43,

44,

45], optical mechanisms for increasing light capture in dim light [

10,

13,

44,

46,

47,

48,

49], and specialized neural mechanisms that enhance visual performance by boosting retinal signal reliability [

50] and by summing photons in space and time [

13,

47,

51,

52]. Light intensity thresholds determine flower search behavior more than other abiotic environmental factors [

11,

53]. Moreover, nocturnal bees tend to visit flowers with a broad reflection spectrum that likely creates a high contrast white target against the dark backgrounds of the sky and vegetation [

53,

54,

55,

56].

In addition to visual adaptations for dim light, nocturnal pollinators often heavily depend on floral odors to find their host flowers [

55]. Indeed, nocturnal bees tend to visit and are attracted by flowers releasing a strong perfume at night [

20,

39,

56], with volatiles from various biosynthetic routes. For example, nocturnal bees are attracted to the strong scent of

Campomanesia phaea (Myrtaceae) flowers, which is mainly composed of aromatic (2-phenylethanol and benzyl alcohol) and aliphatic (1-octanol and 1-hexanol) compounds [

18]. The floral scents emitted by

Paullinia cupana (Sapindaceae) and attractive as a mixture to nocturnal bee pollinators are, among others, the terpenoids linalool and (

E)-β-ocimene, and the nitrogen-bearing compound phenylacetonitrile [

36]. These available data demonstrate that strong floral scents composed of compounds widespread among flower scents [

57] are a key sensory cue used by nocturnal bees to find their host flowers.

3. Traits of Nocturnal Bees and Their Host Plants

As diurnal bees, nocturnal bees depend on floral resources to survive and feed their offspring, and actively seek flowers from which to take up nectar and collect pollen. Some of the pollen grains thereby adhere to the pilosity of their body surface. These grains can subsequently be passively deposited on the stigma of conspecific flowers, completing the pollination process [

58]. Nocturnal bees generally show high flower constancy since individual bees preferentially visit flowers of the conspecific species during a foraging flight, as observed in Myrtaceae [

18,

38,

39,

59] and Caryocaraceae [

20]. Furthermore, nocturnal bees are able to vibrate flowers (

Supplementary Material), which is a quite efficient mechanism for collecting pollen [

33,

60,

61]. This behavior was even observed in plant species with non-poricidal anthers [

18,

39,

59]. In one case, nocturnal bees have been shown to transfer higher quantities of pollen grains to the stigma of flowers than diurnal bees [

18], and are sometimes more abundant floral visitors than diurnal bees [

18,

62].

Nocturnal bees explore different types of flowers. Some floral features certainly favor pollination or visitation by nocturnal bees, such as nocturnal anthesis, high light reflectance, and a strong perfume. However, the forms and sizes of flowers visited by nocturnal bees are quite variable. Among such flowers are large brush blossoms (e.g.,

Caryocar brasiliense) [

20], small zygomorphic flowers (e.g.,

Paullinia cupana) [

36,

37], keel flowers (e.g.,

Machaerium opacum) [

56], and disk flowers (e.g., Myrtaceae species) [

18,

39]. Nocturnal bees also visit plants with different flowering strategies, like those with mass (e.g.,

Plinia cauliflora,

Machaerium opacum) or steady-state flowering (e.g.,

Campomanesia phaea,

Eugenia pyriformis) [

18,

39,

56,

63].

4. Host Plants of Nocturnal Bees

Nocturnal bees visit a wide spectrum of wild and crop plants and they can efficiently pollinate some of them, such as

Cambessedesia wurdackii (Melastomataceae) [

62],

Campomanesia phaea (Myrtaceae) [

18],

Paullinia cupana (Sapindaceae) [

36,

37],

Machaerium opacum (Fabaceae) [

56],

Passiflora pohlii (Passifloraceae) [

64],

Trembleya laniflora (Melastomataceae) [

33], and

Cucurbita species (Cucurbitaceae) [

65,

66]. Several other species are visited by nocturnal bees, but there is still little information about their pollination efficiency. Among such species are

Calathea insignis (Marantaceae) [

67],

Gustavia augusta (Lecythidaceae) [

68],

Parkia velutina (Fabaceae) [

69],

Ipomea species (Convolvulaceae) [

70,

71],

Solanum species (Solanaceae) [

30,

67,

72,

73], and

Eugenia,

Syzygium, and

Plinia species (Myrtaceae) [

39].

Pollen analysis from brood cells of nocturnal bees, or from pollen attached to their bodies, has shown that these bees also visit several chiropterophilous (bat-pollinated) and sphingophilous (moth-pollinated) species [

16,

19,

34,

74]. However, in only a few cases has the role of nocturnal bees as pollinators of these plants been studied. In the bat-pollinated

Cayaponia cabocla (Cucurbitaceae), they are potential pollinators [

75], but in the bat-pollinated tree

Caryocar brasiliense, they efficiently remove floral resources without contributing to fruit set [

20]. In chiropterophilous and sphingophilous flowers that provide easily accessible flowers with abundant pollen and nectar, nocturnal bees seem to generally be poor pollinators due to their morphological mismatch [

20].

Moreover, nocturnal bees are generalists with regard to their food resources, and highly opportunistic. For instance,

Megalopta bees captured on field bioassays in guaraná crops carried only pollen grains of this crop on their body, but other individuals of the same species also carried pollen of other species, mainly Arecaceae and Euphorbiaceae species [

36]. Analysis of brood cell provisions of two

Megalopta species has revealed pollen of 64 plant species from 19 families [

34]. Bees of

Ptiloglossa also visit different night-flowering plants, but in one single brood cell a monofloral pollen load was found [

20]. The Paleotropical bee species

X.

tranquebarica, which visits flowers throughout the night, seems to be a generalist, as it was found to feed on diurnal leftovers from 71 plant species [

76].

5. Nocturnal Bees as Crop Pollinators

Our knowledge concerning crop pollination by nocturnal bees has increased recently (). Nocturnal bees have been recorded to be effective pollinators of regional crops in Brazil, such as cambuci (

Campomanesia phaea-Myrtaceae), which are native to the Atlantic Forest, and guaraná (

Paullinia cupana-Sapindaceae), native to the Amazon region. Both species are cultivated in their original habitat and both have regional economic importance [

18,

36,

37,

77]. Nocturnal bees most likely are pollinators of other Myrtaceae crops in the neotropics, for example of species in the genera

Eugenia,

Campomanesia,

Myrcia, and

Pisidium, which produce fleshy fruits. Flower opening before sunrise and an intense floral scent is common to all these species [

18,

38,

39,

59].

Table 1. List of crop plant families and species known to be pollinated (E = effective, P = potential pollination) by nocturnal bees; nocturnal bee genera that visit them; geographical occurrence; references (Ref.).

|

Plant Family

|

Plant Species

(Popular Name)

|

Nocturnal Bee Genera

|

Role as Pollinators

|

Occurrence

|

Ref.

|

|

Anacardiaceae

|

Spondias mombin

(cajá, yellow mombin)

|

Megalopta, Ptiloglossa

|

E

|

Caatinga-

Brazil

|

[35]

|

| |

Spondias pinnata (wild mango)

|

Xylocopa

|

P

|

Tropical Forest-Southeast Asia

|

[83]

|

|

Cucurbitaceae

|

Cucurbita foetidissima (pumpkin)

|

Peponapis,

Xenoglossa

|

E

|

Dry environments-Mexico/USA

|

[81]

|

| |

Cucurbita maxima

(pumpkin)

|

Peponapis,

Xenoglossa

|

E

|

Dry environments-Mexico/USA

|

[80]

|

| |

Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin)

|

Peponapis,

Xenoglossa

|

E

|

Dry environments-Mexico/USA

|

[65,66,80]

|

|

Myrtaceae

|

Campomanesia phaea (cambuci)

|

Megalopta, Ptiloglossa, Megommation, Zikanapis

|

E

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[18]

|

| |

Campomanesia pubescens

(gabiroba)

|

Megalopta,

Ptiloglossa

|

E

|

Atlantic Forest,

Cerrado-Brazil

|

[84]

|

| |

Eugenia brasiliensis

(grumixama)

|

Megommation

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[39]

|

| |

Eugenia dysenterica

(cagaita)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Cerrado-Brazil

|

[39]

|

| |

Eugenia florida

(guamirim)

|

Megalopta

|

E

|

Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado-Brazil

|

[59]

|

| |

Eugenia involucrata

(cereja-do-Rio-Grande)

|

Megalopta, Megommation

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[39]

|

| |

Eugenia neonitida

(pitangatuba)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[38]

|

| |

Eugenia punicifolia

(cereja-do-cerrado)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado-Brazil

|

[38]

|

| |

Eugenia pyriformis

(uvaia)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[39]

|

| |

Eugenia rotundifolia

(abajurú)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[38]

|

| |

Eugenia stipitata

(araçá-boi)

|

Megalopta, Megommation

|

P

|

Amazon, Atlantic Forest-Brazil

|

[39,85]

|

| |

Eugenia uniflora

(pitanga)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[38,39]

|

| |

Myrciaria floribunda (cambuí)

|

Megalopta

|

E

|

Amazon, Atlantic Forest, Caatinga, Cerrado-Brazil

|

[59]

|

| |

Myrciaria dubia

(camu-camu)

|

Megalopta

|

P

|

Amazon-Brazil

|

[86]

|

| |

Plinia cauliflora

(jabuticaba)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest,

Cerrado-Brazil

|

[39]

|

| |

Psidium acutangulum (araçá-pera)

|

Megalopta

|

P

|

Amazon-Brazil

|

[87]

|

| |

Syzygium malaccense (jambo-rosa)

|

Ptiloglossa

|

P

|

Atlantic Forest-

Brazil

|

[39]

|

|

Sapindaceae

|

Paullinia cupana

(guaraná)

|

Megalopta, Ptiloglossa

|

E

|

Amazon-Brazil

|

[36,37]

|

Nocturnal bees also pollinate flowers of cajá (yellow mombin,

Spondias mombin-Anacardiaceae [

35], which is an economically important and common fruit crop native to and cultivated in Northeast and Northern Brazil, and Central America. The genus

Spondias includes other frequently used fruit crop species (e.g.,

S.

purpurea,

S.

tuberosa) with similar blossoms, nocturnal anthesis periods, and floral resources [

78,

79], that also might be pollinated by nocturnal bees.

In North America, squash bees of the genera

Peponapis and

Xenoglossa display crepuscular flight activity that begins before sunrise.

Xenoglossa is only active during twilight, whereas

Peponapis also forages throughout the day [

65,

66,

80,

81]. Both species are oligolectic on species of

Cucurbita (Cucurbitaceae) and effective pollinators of cultivated pumpkins (

Cucurbita foetidissima,

C.

maxima,

C.

pepo).

Nocturnal bees visit flowers of a broad spectrum of families (at least 40 families) [

82], such as Fabaceae, an important group of cultivated plants, where they show the ability to open the keel, typical for flowers of this family [

56]. Their capacity to vibrate flowers to collect pollen makes nocturnal bees potential pollinators of a range of cultivated plants with poricidal anthers, such as

Solanum species (eggplant, peppers, tomato) [

30,

56,

72,

73].

This demonstrates not only the great potential of nocturnal bees as pollinators but also the necessity of extending observations in crops with nocturnal anthesis to analyze their contribution to pollination and food production in species of economic interest.

6. Requirements on Crop Areas to Host High Numbers of Nocturnal Bees

The biology of nocturnal bees is still poorly understood, and there is no possibility of acquiring nests commercially, as is possible for diurnal bees (e.g.,

Osmia,

Megachile, bumblebees, stingless bees or honeybees), but some strategies to provide appropriate habitats to improve their presence around cropping areas will now be suggested (

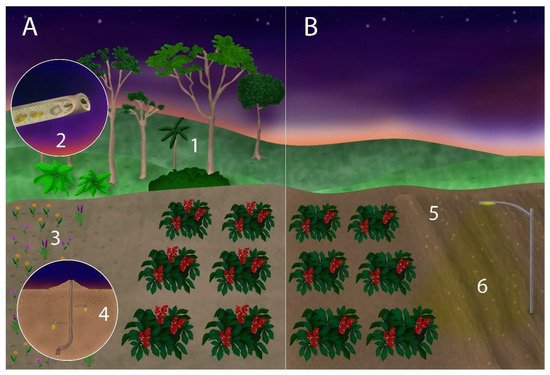

Box 1, ).

Figure 2. Comparing a more (A) and a less (B) sustainable crop area for hosting high numbers of nocturnal bee pollinators. Adjacent natural areas to provide food (1) and nest (2) resources; a range of cultivated, native flowering species offer food beyond the crop flowering season (3); potential nesting sites of ground-nesting species (e.g., Ptiloglossa) should be identified and protected (4); soil disturbance, such as that caused by deep tillage, fire, and superficial movements in the area by agricultural machines should be minimized, at least during the flowering season (5); artificial light pollution at night (ALAN) near crop areas should be avoided (6).