Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Pathology

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is known to be an independent cardiovascular risk factor. Among arousal from sleep, increased thoracic pressure and enhanced sympathetic activation, intermittent hypoxia is now considered as one of the most important pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to the development of endothelial dysfunction. Nevertheless, not much is known about blood components, which justifies the current review.

- obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

- endothelial dysfunction (ED)

- oxidative stress

- nitric oxide (NO)

- asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA)

1. Introduction

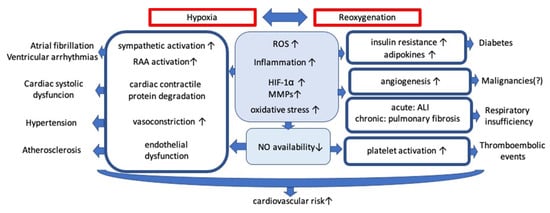

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by recurrent obstruction of the upper airway during sleep causing intermittent hypoxia (IH). The prevalence is increased by advanced age, male sex, higher body mass index and ranges, according to some estimations, from 9% to 38% in general population [1]. OSA is known to be an independent cardiovascular risk factor. The incidence during three years observation of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, and unplanned revascularization in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention was higher in the OSA group (18.9% versus 14.0% in the non-OSA group) [2]. Numerous possible mechanisms contributing to the progression of cardiovascular disorders remain in the focus of interest (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms contributing to the progression of cardiovascular disorders. Abbreviations: ROS: reactive oxygen species; HIF-1α: hypoxia inducible factor 1α; MMPs: matrix metalloproteinases; ALI: acute lung injury; RAA: renin-angiotensin-aldosterone; NO: nitric oxide; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

Among increased thoracic pressure and activation of the sympathetic system, intermittent hypoxia (IH) is now being recognized as a potential major factor contributing to the pathogenesis of OSA-related comorbidities. IH is characterized by cycles of hypoxemia followed by reoxygenation that contribute to the development of the ischemia-reperfusion injury [3]. The biochemical consequences of hypoxia comprise the inhibition of the Krebs cycle and promotion of lactate synthesis. The impairment of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in the course of hypoxia, followed by subsequent reoxygenation, induces the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS generation involves the mitochondrial respiratory chain and numerous enzyme complexes, including the NADPH oxidase, nitric oxide (NO) synthase and the xanthine oxidase [4].

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between the pro-oxidants formation and neutralization. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are toxic highly reactive and unstable compounds. Superoxide reacts with NO creating peroxynitrite (ONOO−) which is a very potent entity, being ~1000× stronger as an oxidizing agent than is H2O2. The ONOO− can influence posttranslational protein modifications altering their structure, activity and function, leading in turn to impairment of signaling pathways. Markers of ONOO− formation (such as nitrotyrosines or isoprostanes) can be found in many disease states including brain injury [5], heart injury [6], preeclampsia [7], and inflammation [8].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can limit NO bioavailability by reacting with cofactors of NO synthase (NOS). ROS cause depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin and alter the ratio of oxidized to reduced glutathione inducing NOS S-glutathionylation [9]. Oxidative stress is strongly attributed to endothelial NOS dysfunction (eNOS uncoupling). Converted to a superoxide-producing enzyme, uncoupled eNOS not only leads to reduction of the NO generation but also potentiates the preexisting oxidative stress. An understanding of the biology of NO, O2− and ONOO− as well as the importance of the NOS uncoupling in physiological and pathological setting are crucial for understanding the nitrosative stress-related controversies. There is a critical balance between cellular concentrations of NO, O2−, and superoxide dismutase, which physiologically favors NO production but in pathological conditions such as ischemia/reperfusion(I/R) results in ONOO− generation.

The NO bioavailability can be also diminished in other possible mechanism involving asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and monomethylated arginine (L-NMMA) which are endogenous competitive inhibitors of the NOS. ADMA plays a role in the development of endothelial dysfunction and is considered as a marker of oxidative stress. Most importantly, OSA is associated with a decrease in the NO bioavailability and changes in the platelet function and erythrocyte rheological disturbances [10].

2. Molecular Consequences of Hypoxia/Reoxygenation (H/R) on Endothelial Function in OSA before CPAP Treatment

There are many mechanisms triggered by the hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Most of them are associated with ROS overproduction and cellular damage. The impact of hypoxemia causing endothelial dysfunction was examined in numerous animal and human in vitro and in vivo models. Intermittent hypoxia in rats impaired endothelial function by attenuating the integrity of endothelium and lowering the number of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) in the blood [11]. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are circulating bone marrow-derived precursors which are capable of excreting microvesicles (MVs) containing gene messages (mRNAs and miRNAs). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs which play a role in several cellular processes. Not only progenitor cells, but also activated endothelial cells and white blood cells are capable of producing the microparticles. MVs may have either beneficial or detrimental effects on endothelial cells. In the medium containing tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) they activate the caspase 3 which leads to apoptosis. MVs transduce information associated with ROS production, inducing angiogenesis and activation of the PI3K/eNOS/NO pathway [12]. MVs released during hypoxia/reoxygenation injury are pro-apoptotic and pro-oxidative [13]. Another study confirms that circulating MVs cause increased permeability and disruption of tight junctions along with increased adhesion molecule expression, reduce eNOS expression and promote increased monocyte adherence. Comparing the influence of microvesicles isolated before and after PAP therapy, the disturbances in endothelial cells function such as increased permeability and disruption of tight junctions were attenuated with treatment [14].

Priou et al. found higher levels of microvesicles derived from granulocytes and activated leukocytes (CD62L+) in patients with the oxyhemoglobin desaturation index (ODI) ≥ 10. MVs have increased expression of endothelial adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1, Integrin alpha-5) and cyclooxygenase 2.

MVs from desaturating patients injected into mice impaired the endothelium-dependent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in aorta and the flow-mediated dilation (FMD) in small mesenteric arteries resulting from decreased NO production. The endothelial NO synthesis negatively correlated with the number of active leukocytes and the sleep apnea severity. In vitro, MVs from desaturating patients reduced endothelial NO production by enhancing phosphorylation of eNOS at the site of inhibition and increasing expression of caveolin-1. Caveolin-1 is a membrane protein which regulates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and takes part in cellular insulin-signaling. In the study by Sharma et al. chronic 3-day intermittent hypoxia (IH) exposure on human coronary artery endothelial cells increased caveolin-1 and endothelin-1 expression resulting in decreased NO bioavailability [15][16].

Skin biopsies obtained from OSA patients with severe nocturnal hypoxemia demonstrate a significant upregulation of eNOS, TNFα-induced protein 3, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) [17]. The expression of endothelial-cell-specific molecule-1 (ESM-1, Endocan), VEGF and HIF-1α was also significantly increased in the human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) subjected to IH and in patients with OSA. ESM-1 is upregulated by the HIF-1α/VEGF pathway under IH in endothelial cells, playing a critical role in enhancing adhesion between monocytes and endothelial cells [18]. IH increased advanced glycation end products formation and activated NF-кB signaling in monocytes, resulting in enhanced monocyte adhesion, chemotaxis, and promoted macrophage polarization toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype [19]. Enhancing adhesion and infiltration activity monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) was also increased in monocytes under IH [20]. Moreover increased macrophage population with pro-inflammatory expression of CD36 and Ly6c was confirmed in the aortic wall in a murine model of IH [21]. In mice nocturnal intermittent hypoxia increased mRNA levels of 5-lipoxygenase and CysLT1 receptor, which was strongly associated with atherosclerosis lesion size. That confirms cysteinyl-leukotrienes (CysLT) pathway activation as a potential mechanism responsible for developing atherosclerosis connected with IH [22]. Another study trying to explain OSA-dependent atherogenesis found an increased expression of toll-like receptors (TLRs) and receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) in atherosclerotic plaques from patients with severe OSA [23].

An in vitro model of OSA shows that endothelial cells originating from distinct vascular beds respond differently to intermittent hypoxia. In human dermal microvascular endothelial cells IH decreased the expression of eNOS and HIF-1α, while in coronary artery endothelial cells HIF-1α expression was increased [17]. The HIF-1α activates the NFκB, a transcription factor which regulates several pro-inflammatory genes, including TNFα, interleukin (IL)-8, and IL-6 [24]. IL-6, the epidermal growth factor family ligands, and tyrosine kinase receptors induced by IH may be involved in the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [25]. Another study showed that a further vascular and cardiac dysfunction in mice under IH can be triggered by trombospondin-1 though cardiac fibroblast activation and increasing angiotensin II activity [26].

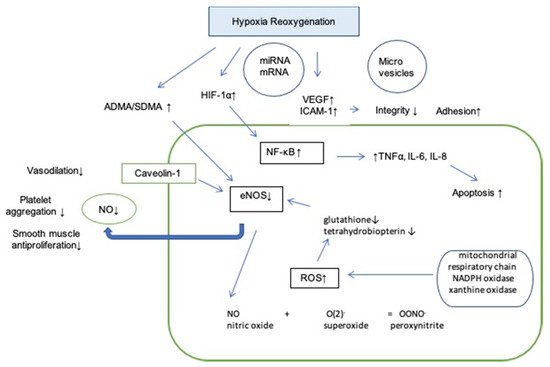

In conclusion, OSA may result in endothelial dysfunction by limiting the NO availability, promoting oxidative stress, up-regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Microparticles and signaling factors lead to lower permeability of endothelial cells, enhanced adhesion and increased apoptosis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Influence of hypoxia reoxygenation on endothelium. Abbreviations: HIF-1α: hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule 1; NF- κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL-6: interleukin 6; IL-8: interleukin 8; SDMA: symmetric dimethylarginine; ADMA: asymmetric dimethylarginine; ROS: reactive oxygen species; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO: nitric oxide; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

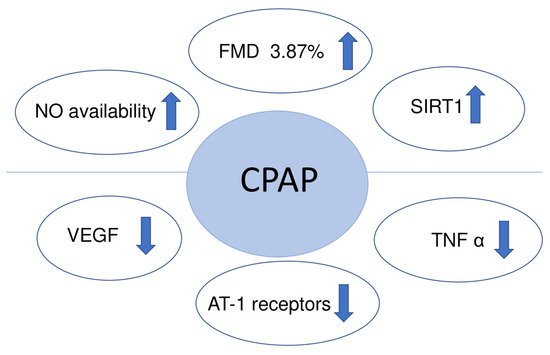

3. Endothelial Function after Treatment with CPAP

An appropriate CPAP therapy in randomized control trials conducted on OSA patients improved flow mediated dilation (FMD), suggesting its potentially beneficial role in cardiovascular risk reduction [27][28]. A meta-analysis confirms that CPAP increases the absolute FMD value by a mean of 3.87% [29]. Flow mediated dilation (FMD) measures the change of the brachial artery diameter after a brief period of forearm ischemia. It helps to assess endothelial function and its ability to dilate the vessel by producing NO and prostacyclin. There are many other physical methods to assess endothelial function including venous occlusion plethysmography, peripheral arterial tonometry (PAT) and optical techniques using laser doppler flowmetry (LDF) that can be coupled with provocation tests (post-ischemic hyperemia, local heating). However, more studies are needed in order to validate their usefulness in assessing endothelial dysfunction.

As far as the literature is concerned, the effect of CPAP on inflammatory reaction is not proven yet. Inflammatory markers such as IL-8, hs-CRP, and TNF-α did not significantly change from baseline after 1 year CPAP therapy [30]. However, the use of CPAP for at least 5 h per night decreased TNF-α levels in women suffering from OSA [31]. Interestingly, CPAP tends to lower TNF-α, which is initially increased in OSA patients [32]. These diverse effects of CPAP treatment could be explained by a low adherence to the therapy and the fact that better effects are observed with the therapy duration of ≥3 months and more adequate compliance (≥4 h/night).

Another positive effect after 12 weeks of CPAP therapy was a decreased expression of angiotensin receptors type-1 (AT-1R) measured in the gluteal subcutaneous tissue [33]. The AT-1R mediates the major cardiovascular effects of angiotensin II, including cardiac hypertrophy, augmentation of peripheral noradrenergic activity and vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation.

Three months of CPAP treatment significantly increased the level of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and serum levels of NO derivative in the blood [34]. SIRT1 is a histone/protein deacetylase which regulates the eNOS, restores the NO availability and is involved in different aspects of aging, metabolism, stress resistance and cardiovascular disease.

Patients with OSA showed a higher adventitial vasa vasorum density, correlating with AHI [35]. This could be explained by increased VEGF activity induced by IH. One meta-analysis confirmed that CPAP therapy improved endothelial function associated with VEGF lowering [36]. On the contrary, short return of OSA using sham CPAP for 2 weeks was not associated with changes in endocan, ET-1, resistin and VEGF. However, a significant decrease in vasodilatory peptide adrenomedullin was found [37][38]. Adrenomedullin is a protective endothelial product stimulated by IH, which could partially explain why the CPAP therapy may deteriorate endothelial function or exert a neutral effect in the short-term observational studies.

In the moderate to severe OSA, the 2-month CPAP treatment vs. sham did not reduce the plasma concentrations oxidative stress-related markers [39]. In a study by Borges comparing the 8-week CPAP therapy with aerobic training, no significant changes regarding oxidative stress markers and cell-free DNA levels were detected [40]. Interesting outcomes were shown in a mice model study, where the animals treated with a high-fat diet revealed a positive effect of the low-frequency hypoxia. The serum levels of the oxidative stress markers were increased in the mice treated with a high-frequency intermittent hypoxia (60 hypoxic events/h) and decreased by treating with a low frequency hypoxia (10 events/h) [41]. That could be partially explained by the activation of protective mechanisms during IH.

Although there is substantial evidence that CPAP improves endothelial function (Figure 3), the antioxidant capacity is not changed significantly. The median plasma nitrite level and total antioxidant status did not show any significant difference between the OSA and the control groups. Nevertheless, the oxidant-antioxidant balance was shifted toward the oxidant side in OSA cases [42].

Figure 3. Endothelial function after treatment with CPAP. Abbreviations: VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; NO: nitric oxide; FMD: flow mediated dilation; SIRT1: sirtuin 1; TNFα: tumor necrosis factor alpha; AT-1 receptors: expression of angiotensin receptors type-1; ↑: increased; ↓: decreased.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22105139

References

- Senaratna, C.V.; Perret, J.L.; Lodge, C.J.; Lowe, A.J.; Campbell, B.E.; Matheson, M.C.; Hamilton, G.S.; Dharmage, S.C. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2017, 34, 70–81.

- Lee, C.H.; Sethi, R.; Li, R.; Ho, H.H.; Hein, T.; Jim, M.H.; Loo, G.; Koo, C.Y.; Gao, X.F.; Chandra, S.; et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2016, 133, 2008–2017.

- Dewan, N.A.; Nieto, F.J.; Somers, V.K. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA: Implications for comorbidities. Chest 2015, 147, 266–274.

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. 2003, 552, 335–344.

- Picón-Pagès, P.; Garcia-Buendia, J.; Muñoz, F.J. Functions and dysfunctions of nitric oxide in brain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 1949–1967.

- Kooy, N.W.; Lewis, S.J.; Royall, J.A.; Ye, Y.Z.; Kelly, D.R.; Beckman, J.S. Extensive tyrosine nitration in human myocardial inflammation: Evidence for the presence of peroxynitrite. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 25, 812–819.

- Roggensack, A.M.; Zhang, Y.; Davidge, S.T. Evidence for Peroxynitrite Formation in the Vasculature of Women with Preeclampsia. Hypertension 1999, 33, 83–89.

- Ohmori, H.; Kanayama, N. Immunogenicity of an inflammation-associated product, tyrosine nitrated self-proteins. Autoimmun. Rev. 2005, 4, 224–229.

- De Pascali, F.; Hemann, C.; Samons, K.; Chen, C.A.; Zweier, J.L. Hypoxia and reoxygenation induce endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling in endothelial cells through tetrahydrobiopterin depletion and S-glutathionylation. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 3679–3688.

- Alonso-Fernandez, A.; Garcia-Rio, F.; Arias, M.A.; Hernanz, A.; de la Pena, M.; Pierola, J.; Barcelo, A.; Lopez-Collazo, E.; Agusti, A. Effects of CPAP on oxidative stress and nitrate efficiency in sleep apnoea: A randomised trial. Thorax 2009, 64, 581–586.

- Tuleta, I.; França, C.N.; Wenzel, D.; Fleischmann, B.; Nickenig, G.; Werner, N.; Skowasch, D. Intermittent Hypoxia Impairs Endothelial Function in Early Preatherosclerosis. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 858, pp. 1–7.

- Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Ma, X.; Cheng, C.; Xiao, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, B.; Chen, Y. Effects of endothelial progenitor cell-derived microvesicles on hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 572729.

- Zhang, Q.; Shang, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Song, J.; Liu, Y. Microvesicles derived from hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated human umbilical vein endothelial cells promote apoptosis and oxidative stress in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. BMC Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 25.

- Bhattacharjee, R.; Khalyfa, A.; Khalyfa, A.A.; Mokhlesi, B.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; Almendros, I.; Peris, E.; Malhotra, A.; Gozal, D. Exosomal cargo properties, endothelial function and treatment of obesity hypoventilation syndrome: A proof of concept study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2018, 14, 797–807.

- Priou, P.; Gagnadoux, F.; Tesse, A.; Mastronardi, M.L.; Agouni, A.; Meslier, N.; Racineux, J.L.; Martinez, M.C.; Trzepizur, W.; Andriantsitohaina, R. Endothelial dysfunction and circulating microparticles from patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 974–983.

- Sharma, P.; Dong, Y.; Somers, V.K.; Peterson, T.E.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, G.; Singh, P. Intermittent hypoxia regulates vasoactive molecules and alters insulin-signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14110.

- Kaczmarek, E.; Bakker, J.P.; Clarke, D.N.; Csizmadia, E.; Kocher, O.; Veves, A.; Tecilazich, F.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Ferran, C.; Malhotra, A. Molecular Biomarkers of Vascular Dysfunction in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70559.

- Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, K.; Wu, H.; Zhan, X.; Fang, F.; Qin, Y.; Wei, Y. ESM-1 promotes adhesion between monocytes and endothelial cells under intermittent hypoxia. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 1512–1521.

- Zhou, J.; Bai, W.; Liu, Q.; Cui, J.; Zhang, W. Intermittent Hypoxia Enhances THP-1 Monocyte Adhesion and Chemotaxis and Promotes M1 Macrophage Polarization via RAGE. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1650456.

- Chuang, L.P.; Chen, N.H.; Lin, Y.; Ko, W.S.; Pang, J.H.S. Increased MCP-1 gene expression in monocytes of severe OSA patients and under intermittent hypoxia. Sleep Breath. 2016, 20, 425–433.

- Gileles-Hillel, A.; Almendros, I.; Khalyfa, A.; Zhang, S.X.; Wang, Y.; Gozal, D. Early intermittent hypoxia induces proatherogenic changes in aortic wall macrophages in a murine model of obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 958–961.

- Gautier-Veyret, E.; Bäck, M.; Arnaud, C.; Belaïdi, E.; Tamisier, R.; Lévy, P.; Arnol, N.; Perrin, M.; Pépin, J.L.; Stanke-Labesque, F. Cysteinyl-leukotriene pathway as a new therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis related to obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 134, 311–319.

- Olejarz, W.; Głuszko, A.; Cyran, A.; Bednarek-Rajewska, K.; Proczka, R.; Smith, D.F.; Ishman, S.L.; Migacz, E.; Kukwa, W. TLRs and RAGE are elevated in carotid plaques from patients with moderate-to-severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 1573–1580.

- Williams, A.; Scharf, S.M. Obstructive sleep apnea, cardiovascular disease, and inflammation—Is NF-κB the key? Sleep Breath. 2007, 11, 69–76.

- Kyotani, Y.; Takasawa, S.; Yoshizumi, M. Proliferative pathways of vascular smooth muscle cells in response to intermittent hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2706.

- Bao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Suo, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Yuan, M.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G. Intermittent hypoxia mediated by TSP1 dependent on STAT3 induces cardiac fibroblast activation and cardiac fibrosis. eLife 2020, 9, e49923.

- Panoutsopoulos, A.; Kallianos, A.; Kostopoulos, K.; Seretis, C.; Koufogiorga, E.; Protogerou, A.; Trakada, G.; Kostopoulos, C.; Zakopoulos, N.; Nikolopoulos, I. Effect of CPAP treatment on endothelial function and plasma CRP levels in patients with sleep apnea. Med. Sci. Monit. 2012, 18, CR747–CR751.

- Ning, Y.; Zhang, T.S.; Wen, W.W.; Li, K.; Yang, Y.X.; Qin, Y.W.; Zhang, H.N.; Du, Y.H.; Li, L.Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiovascular biomarkers in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Breath. 2019, 23, 77–86.

- Schwarz, E.I.; Puhan, M.A.; Schlatzer, C.; Stradling, J.R.; Kohler, M. Effect of CPAP therapy on endothelial function in obstructive sleep apnoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respirology 2015, 20, 889–895.

- Thunström, E.; Glantz, H.; Yucel-Lindberg, T.; Lindberg, K.; Saygin, M.; Peker, Y. Cpap does not reduce inflammatory biomarkers in patients with coronary artery disease and nonsleepy obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2017, 40, zsx157.

- Campos-Rodriguez, F.; Asensio-Cruz, M.I.; Cordero-Guevara, J.; Jurado-Gamez, B.; Carmona-Bernal, C.; Gonzalez-Martinez, M.; Troncoso, M.F.; Sanchez-Lopez, V.; Arellano-Orden, E.; Garcia-Sanchez, M.I.; et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on inflammatory, antioxidant, and depression biomarkers in women with obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz145.

- Arias, M.A.; García-Río, F.; Alonso-Fernández, A.; Hernanz, Á.; Hidalgo, R.; Martínez-Mateo, V.; Bartolomé, S.; Rodríguez-Padial, L. CPAP decreases plasma levels of soluble tumour necrosis factor-α receptor 1 in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 32, 1009–1015.

- Khayat, R.N.; Varadharaj, S.; Porter, K.; Sow, A.; Jarjoura, D.; Gavrilin, M.A.; Zweier, J.L. Angiotensin Receptor Expression and Vascular Endothelial Dysfunction in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Am. J. Hypertens. 2018, 31, 355–361.

- Chen, W.J.; Liaw, S.F.; Lin, C.C.; Chiu, C.H.; Lin, M.W.; Chang, F.T. Effect of Nasal CPAP on SIRT1 and Endothelial Function in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Lung 2015, 193, 1037–1045.

- López-Cano, C.; Rius, F.; Sánchez, E.; Gaeta, A.M.; Betriu, À.; Fernández, E.; Yeramian, A.; Hernández, M.; Bueno, M.; Gutiérrez-Carrasquilla, L.; et al. The influence of sleep apnea syndrome and intermittent hypoxia in carotid adventitial vasa vasorum. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211742.

- Qi, J.C.; Zhang, L.J.; Li, H.; Zeng, H.; Ye, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure on vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2019, 23, 5–12.

- Turnbull, C.D.; Rossi, V.A.; Santer, P.; Schwarz, E.I.; Stradling, J.R.; Petousi, N.; Kohler, M. Effect of OSA on hypoxic and inflammatory markers during CPAP withdrawal: Further evidence from three randomized control trials. Respirology 2017, 22, 793–799.

- Schulz, R.; Flötotto, C.; Jahn, A.; Eisele, H.J.; Weissmann, N.; Seeger, W.; Rose, F. Circulating adrenomedullin in obstructive sleep apnoea. J. Sleep Res. 2006, 15, 89–95.

- Paz, Y.; Mar, H.L.; Hazen, S.L.; Tracy, R.P.; Strohl, K.P.; Auckley, D.; Bena, J.; Wang, L.; Walia, H.K.; Patel, S.R.; et al. Effect of Continuous Positive Airway Pressure on Cardiovascular Biomarkers: The Sleep Apnea Stress Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest 2016, 150, 80–90.

- Borges, Y.G.; Cipriano, L.H.C.; Aires, R.; Zovico, P.V.C.; Campos, F.V.; de Araújo, M.T.M.; Gouvea, S.A. Oxidative stress and inflammatory profiles in obstructive sleep apnea: Are short-term CPAP or aerobic exercise therapies effective? Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 541–549.

- Lee, M.Y.K.; Ge, G.; Fung, M.L.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Mak, J.C.W.; Ip, M.S.M. Low but not high frequency of intermittent hypoxia suppresses endothelium-dependent, oxidative stress-mediated contractions in carotid arteries of obese mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 125, 1384–1395.

- Bozkurt, H.; Neyal, A.; Geyik, S.; Taysi, S.; Anarat, R.; Bulut, M.; Neyal, A.M. Investigation of the plasma nitrite levels and oxidant-antioxidant status in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Noropsikiyatri Ars. 2015, 52, 221–225.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!